ABSTRACT

Azole resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus is a global problem. The major resistance mechanism is through cytochrome P450 14-α sterol demethylase Cyp51A alterations such as a mutation(s) in the gene and the acquisition of a tandem repeat in the promoter. Although other azole tolerance and resistance mechanisms, such as the hmg1 (a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme-A reductase gene) mutation, are known, few reports have described studies elucidating non-Cyp51A resistance mechanisms. This study explored genes contributing to azole tolerance in A. fumigatus by in vitro mutant selection with tebuconazole, an azole fungicide. After three rounds of selection, we obtained four isolates with low susceptibility to tebuconazole. These isolates also showed low susceptibility to itraconazole and voriconazole. Comparison of the genome sequences of the isolates obtained and the parental strain revealed a nonsynonymous mutation in MfsD, a major facilitator superfamily protein (Afu1g11820; R337L mutation [a change of R to L at position 337]), in all isolates. Furthermore, nonsynonymous mutations in AgcA, a mitochondrial inner membrane aspartate/glutamate transporter (Afu7g05220; E535Stop mutation), UbcD, a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 (Afu3g06030; T98K mutation), AbcJ, an ABC transporter (Afu3g12220; G297E mutation), and RttA, a putative protein responsible for tebuconazole tolerance (Afu7g04740; A83T mutation), were found in at least one isolate. Disruption of the agcA gene led to decreased susceptibility to azoles. Reconstruction of the A83T point mutation in RttA led to decreased susceptibility to azoles. Reversion of the T98K mutation in UbcD to the wild type led to decreased susceptibility to azoles. These results suggest that these mutations contribute to lowered susceptibility to medical azoles and agricultural azole fungicides.

KEYWORDS: Aspergillus fumigatus, azoles, drug resistance

INTRODUCTION

Aspergillus fumigatus, a filamentous fungus commonly found in the natural environment, is known to be the major causative agent of aspergillosis. The 2- to 3-μm-diameter conidia are dispersed easily in the air, by which they can reach the human lung alveoli. The fungus colonizes and invades lung tissue of immunocompromised hosts or hosts with local immunosuppression in the lung, leading to aspergillosis. Recent global estimates indicate that 3 million cases of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis and 0.3 million cases of invasive aspergillosis occur annually, each with high mortality, even if treated (1–3).

Azole antifungals are frontline agents for aspergillosis treatment. Therefore, the emergence of azole resistance in A. fumigatus has raised global concern. As demonstrated in earlier studies (4–10), azole-resistant strains often appear during treatment. Mutations responsible for resistance were found mainly in Cyp51A (Erg11; cytochrome P450 14-α sterol demethylase), which is the target protein of azole antifungals (11, 12). Genes encoding a putative ABC transporter (cdr1B) (13), a subunit of the CCAAT-binding transcription factor complex (hapE) (14), and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme-A reductase (hmg1) (4) have been identified as non-cyp51A genes responsible for azole resistance in clinical isolates. Nevertheless, few reports provide relevant information about them.

Azole antifungals have also been used worldwide as agricultural fungicides. The agricultural azole fungicides and medical azoles share an antifungal mechanism. Tolerance of the fungicides might confer cross-resistance to medical azoles. Consequently, the fungicide residues are thought to act as a selective pressure in the soil, which has led to the appearance of azole-resistant A. fumigatus in the environment (15, 16). The prevalent environmental azole-resistant strains also include mutation(s) in cyp51A. They also acquire a tandem repeat (TR) in the promoter (17). Tebuconazole (TBCZ) is a widely used agricultural fungicide. Ren et al. (18) and Cui et al. (19) reported that TBCZ selection induced cyp51A mutations with a TR in the promoter. Zhang et al. also induced azole resistance in vitro through the pressure of fungicides including TBCZ. Mutations induced in the isolates obtained were found through genome sequencing (20). However, few such studies have been conducted to elucidate the genes responsible for azole tolerance and resistance.

For this study, we induced mutations with TBCZ selection pressure in vitro, demonstrating that we obtained four isolates with lowered susceptibility to TBCZ. These isolates also showed lowered susceptibility to medical azoles and TBCZ. Furthermore, three genes contributing to azole tolerance were identified and confirmed.

RESULTS

In vitro selection of the isolate adapted to TBCZ.

We screened A. fumigatus isolates using three-round selection for the 1/2 MIC of TBCZ in vitro. After the initial selection round, three and seven colonies were obtained on potato dextrose agar plates with 10 mM uracil (PDA/Ura) containing 4 and 2 μg/ml TBCZ, respectively. Eleven colonies on PDA/Ura with 1 μg/ml TBCZ were not used for the next cycle. After the second selection round, four, three, and three colonies were obtained on PDA/Ura containing 16, 8, and 4 μg/ml TBCZ, respectively. After the third selection round, we obtained only seven colonies on PDA/Ura containing 64, 32, and 16 μg/ml TBCZ (2, 3, and 2 colonies, respectively). Two, three, and two clones from the first, second, and third selection rounds, respectively, did not produce any colonies after being transferred to PDA/Ura slants. After the third selection round, one clone was excluded from further analyses because a contaminant was recognized under microscopic observation. Finally, four isolates were obtained: TBCZ31, TBCZ33, TBCZ34, and TBCZ37. In addition, the MICs of TBCZ were determined (Table 1). The four isolates showed high MICs of TBCZ, 8 to 32 μg/ml (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of nonsynonymous gene mutations

| Selection round | Strain | Presence or absence of indicated mutationa |

MIC of TBCZ (μg/ml) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MfsD R337L | UbcD T98K | AbcJ G297E | AgcA E535Stop | RttA A83T | Afu6g01930 G160G (synonymous) | |||

| 1 | TBCZ13 | NDc | 4 | |||||

| TBCZ14 | ND | 2 | ||||||

| TBCZ15 | ○b | ND | 4 | |||||

| TBCZ16 | ND | 2 | ||||||

| TBCZ17 | ND | 4 | ||||||

| TBCZ18 | ND | 8 | ||||||

| TBCZ19 | ND | 2 | ||||||

| TBCZ10 | ND | 4 | ||||||

| 2 | TBCZ21 | ○ | ND | 16 | ||||

| TBCZ23 | ○ | ○b | 8 | |||||

| TBCZ24 | ○ | ○ | ○ | 8 | ||||

| TBCZ25 | ND | 8 | ||||||

| TBCZ28 | ND | 16 | ||||||

| TBCZ29 | ○ | ND | 8 | |||||

| TBCZ20 | ND | 8 | ||||||

| 3 | TBCZ31 | ○ | ○ | 8 | ||||

| TBCZ33 | ○ | ○ | 16 | |||||

| TBCZ34 | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | 32 | |||

| TBCZ37 | ○ | ○ | 32 | |||||

Blank cells show there was no nonsynonymous mutation.

The base-called nucleotide was a mixture of mutated and wild type.

ND, not determined.

Macroscopic phenotype of isolates obtained.

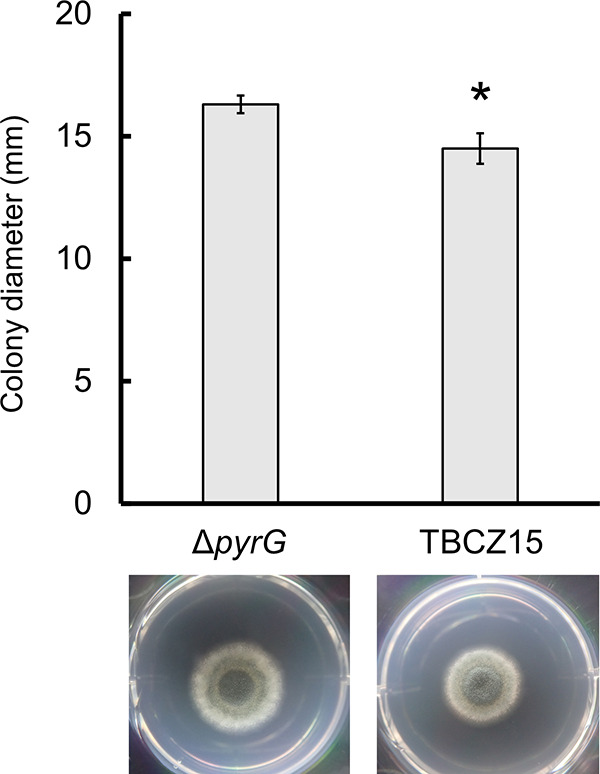

Images of colonies of TBCZ31, TBCZ34, and TBCZ37 are presented in Fig. 1. The TBCZ34 colony diameter was larger than that of the parental strain (ΔpyrG). The TBCZ31 and TBCZ37 colonies had slightly smaller diameters than colonies of the parental strain, but the difference was not significant (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

The appearance and diameters of colonies of ΔpyrG, TBCZ31, TBCZ34, and TBCZ37 strains. Representative macroscopic images and colony diameters after culturing on MM with 10 mM uracil at 35°C for 96 h are shown. Bars and error bars represent the mean values ± standard deviations (SD) from three independent colonies. The asterisk denotes a significant difference (P < 0.01).

Cross-resistance of TBCZ-adapted isolates to medical azoles.

We measured the MICs of medical antifungals itraconazole (ITCZ), voriconazole (VRCZ), posaconazole (PSCZ), and amphotericin B (AMPH) against obtained isolates TBCZ31, TBCZ33, TBCZ34, and TBCZ37. Every isolate was grown in 4 μg/ml VRCZ (Table 2), in a 2-μg/ml or higher concentration of ITCZ, and in a 0.25-μg/ml or higher concentration of PSCZ. The MICs of the nonazole antifungal AMPH were not higher in the isolates (Table 2). These data show that these isolates acquired cross-resistance to the medical azoles via TBCZ selection.

TABLE 2.

MICs of antifungals against TBCZ31, TBCZ33, TBCZ34, and TBCZ37

| Strain | Genotype | MIC (μg/ml) ofa: |

Source or description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITCZ | VRCZ | PSCZ | AMPH | |||

| ΔpyrG strain | akuA::loxP ΔpyrG | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.063 | 1 | This study, derived from AfS35 |

| TBCZ31 | akuA::loxP ΔpyrG mfsDR337LagcAE535Stop | 2 | 4 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| TBCZ33 | akuA::loxP ΔpyrG mfsDR337LagcAE535Stop | 2 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| TBCZ34 | akuA::loxP ΔpyrG mfsDR337LubcDT98KabcJG297E | >8 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| TBCZ37 | akuA::loxP ΔpyrG mfsDR337LrttAA83T | 2 | 4 | 0.25 | 1 | |

| TBCZ15 | akuA::loxP ΔpyrG mfsDR337L | 0.5 | 2 | 0.125 | 1 | |

| AfS35 | akuA::loxP | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.063 | 0.5 | Fungal Genetics Stock Center (strain A1159) |

| ΔmfsD strain | akuA::loxP mfsD::hph | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.063 | 0.5 | This study |

| ΔagcA strain | akuA::loxP agcA::hph | 0.25 | 1 | 0.063 | 0.5 | This study |

| rttAwt strain | akuA::loxP hph | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.032 | 1 | hph gene cassette was inserted between Afu7g04735 and rttA |

| rttAA83T strain | akuA::loxP rttAA83Thph | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.063 | 1 | rttA was replaced with rttAA83T; hph gene cassette was inserted between Afu7g04735 and rttA |

MICs were determined at 48 h after inoculation.

Nonsynonymous mutations are detected in TBCZ-adapted isolates.

To identify the mutations affecting azole susceptibility, TBCZ31, TBCZ33, TBCZ34, and TBCZ37 isolates were subjected to genome sequencing. Comparison to the parental strain showed that a nonsynonymous mutation in a major facilitator superfamily (MFS) gene, mfsD (Afu1g11820), was present in all four isolates (Table 1). A nonsynonymous mutation in a mitochondrial inner membrane aspartate/glutamate transporter gene, agcA (Afu7g05220), was found in TBCZ31 and TBCZ33. Nonsynonymous mutations in ubcD (Afu3g06030) and abcJ (Afu3g12220) were found in TBCZ34. The results of homology analysis show that ubcD is a homolog of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (also known as E2 enzyme) gene and that abcJ encodes a member of the ABC transporters. Mutations in a hypothetical gene annotated as responsible for TBCZ tolerance, rttA (Afu7g04740), were identified in TBCZ37. These mutations were not found in clinical and environmental strains registered in FungiDB (21). Isolates obtained from the first and second selection rounds were examined using Sanger sequencing to confirm the step in which each mutation appeared during in vitro selection (Table 1). The mutation in mfsD was detected in an isolate after the first selection round. Four of seven isolates were found to have the mutation after the second round. The T98K mutation (a change of T to K at position 98) in UbcD and G297E in AbcJ were detected in TBCZ23 and TBCZ24, respectively, after the second selection round. Mutations in agcA and rttA were found in no isolate after the second round. These data suggest that the R337L mutation in MfsD appeared initially, then the T98K mutation in UbcD, and finally, the mutation in AgcA or RttA was introduced into the population. In the obtained strains, we were unable to find any duplication introduced by the selection.

Growth modulation by mfsD R337L mutation.

To elucidate the effects of the R337L mutation in MfsD, we investigated the susceptibility of TBCZ15, obtained after the first selection round (Table 1). The growth of TBCZ15 was slower than that of the parental strain (Fig. 2), suggesting that the mutation led to slower growth in A. fumigatus. As shown in Table 2, the azole MICs were higher against TBCZ15 than against the parental strain. These results suggest that the mutation in MfsD conferred azole tolerance. Next, we constructed an mfsD disruptant from A. fumigatus AfS35 and examined its susceptibility to antifungals. Disruptants showed larger colony diameters than the parental strain, but the difference was small (Fig. 3). We were unable to detect any difference between disruptants and the parental strain in terms of susceptibility to azoles (Table 2). The effect of the R337L mutation of MfsD might be different from the effect of the gene disruption.

FIG 2.

The appearance and diameters of colonies of TBCZ15 and the parental strain (ΔpyrG) cultured on MM with 10 mM uracil at 35°C for 96 h. Macroscopic images of TBCZ15 and the parental strain and colony diameters are shown. Bars and error bars represent the mean values ± SD from three independent colonies. The asterisk denotes a significant difference (P < 0.05).

FIG 3.

The appearance and diameters of colonies of mfsD disruption strains. Macroscopic images and diameters of two independent mfsD disruption strains, ΔmfsD-1 and ΔmfsD-2, and their parental strain AfS35, cultured on MM at 35°C for 72 h, are shown. Bars represent the mean values ± SD from three independent colonies.

Reduced susceptibility to azoles in agcA disruptant and agcA mutation revertant.

We attempted to ascertain whether a mutation in agcA was involved in azole resistance. The mutation in agcA found in TBCZ31 and TBCZ33 was a nonsense mutation at the 535th codon, which caused the impairment of 163 amino acids from the C terminus of AgcA. We hypothesized that the impairment led to functional disruption of AgcA. Therefore, we constructed an agcA disruptant mutant by replacing the gene with the hygromycin resistance gene in A. fumigatus AfS35. The ΔagcA disruptant strain exhibited normal growth (Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The MIC of VRCZ against the ΔagcA strain was 1 μg/ml, which was higher than the MIC against the parental strain (0.5 μg/ml). Additionally, we prepared a revertant strain, TBCZ31to21, possessing the agcA mutation from a stop codon to the original glutamate codon at the 535th residue, resulting in the revertant showing higher susceptibility to ITCZ and VRCZ than the control strain (TBCZ31to31) retaining the stop codon (Table S3). The result suggests that agcA plays a role in azole susceptibility.

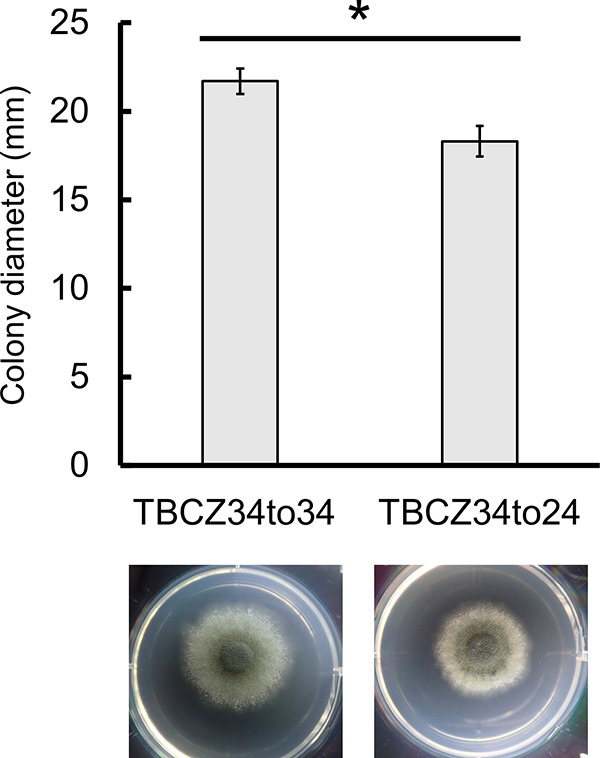

Azole susceptibility reduced by the mutation in ubcD.

We examined whether the mutation in UbcD played a role in azole susceptibility. We tried to disrupt ubcD in A. fumigatus AfS35, with the result that no transformant was obtained. Instead, we tried to construct a strain for which the mutation of ubcD in TBCZ34 was replaced with a wild-type (wt) ubcD gene. The susceptibilities to ITCZ and VRCZ of the resultant isolates were comparable to those of the parental strain (Table 2). Furthermore, a revertant mutant, TBCZ34to24, which contained a tyrosine codon at the 98th residue of UbcD in TBCZ34, showed higher susceptibility to ITCZ and VRCZ than the control strain TBCZ34to34, which retained the T98K mutation in TBCZ34 (Table S3). This result suggests that the mutation in UbcD was responsible for azole resistance. The growth of TBCZ34to24 was significantly slower than that of TBCZ34to34 (Fig. 4), suggesting that the mutation accelerated the growth of A. fumigatus.

FIG 4.

The appearance and diameters of colonies of TBCZ34to34 and TBCZ34to24. Representative macroscopic images and colony diameters after culturing on MM with 10 mM uracil at 35°C for 96 h are shown. Bars represent the mean values ± SD from three independent colonies. The asterisk denotes a significant difference (P < 0.01).

Azole susceptibility reduced by the introduction of the mutation in rttA.

We tried to ascertain whether the mutation in RttA plays a role in azole susceptibility. However, we were unable to disrupt rttA in A. fumigatus strain AfS35. Therefore, we sought to introduce a mutation (A83T) in RttA of the AfS35 strain (Fig. S6 shows the construction). Strain rttAA83T showed lower susceptibility to VRCZ than the control strain rttAwt. We prepared a revertant containing the original alanine codon at the 83rd residue of RttA in TBCZ37 (TBCZ37to21); however, no difference in azole susceptibility was observed between the revertant and the control strain TBCZ37to37 (Table S3). These results suggest that the A83T mutation in RttA contributes to the azole tolerance but that the contribution is small.

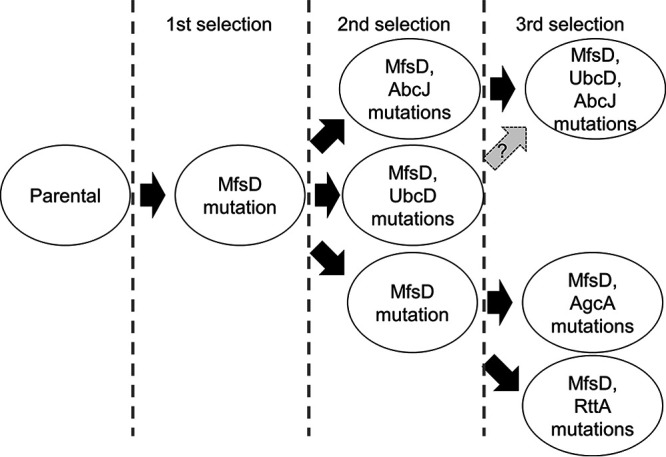

DISCUSSION

For this study, we identified five nonsynonymous mutations in the mfsD, ubcD, abcJ, agcA, and rttA genes. For four of those genes (mfsD, ubcD, abcJ, and rttA), a relation to azole tolerance has never been reported. The mutations and the order in which they occurred are depicted in Fig. 5. A synonymous mutation in Afu6g01930 was found in strains TBCZ24 and TBCZ34 but not in strain TBCZ23. Therefore, we estimated that TBCZ34 was derived from TBCZ24 (Fig. 5). However, the evolution routes are an assumption because multiple isolates were used in each passage, which is a limitation of the study.

FIG 5.

Putative adaptation routes for TBCZ in this study.

During the three selection rounds, one strain with an R337L mutation in the mfsD gene was isolated among eight strains from the first selection round. The mutation was also detected in four of eight strains isolated from the second selection round and in all four strains from the third selection round (Table 1). This result reflects that the R337L mutation in MfsD was enriched among the strains. The mfsD gene encodes an MFS transporter. Several MFS transporters have been reported as factors involved in azole resistance (22, 23). The disruption of the gene did not affect azole susceptibility compared to that of the parental strain. Therefore, further analysis is necessary to elucidate why the mutation is conserved in the strains obtained in this study.

The nonsense mutation at the 535th residue in AgcA and disruption of agcA caused the azole tolerance phenotype. AgcA homologs are found broadly; for example, they occur in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Agc1p) and humans (SLC25A12, also known as Aralar, and SLC25A13, also known as ARALAR2, CITRIN, or CTLN2). These proteins are mitochondrial inner membrane aspartate/glutamate transporters (24, 25) composing the malate-aspartate NADH shuttle (26). Song and colleagues reported that the deletion of A. fumigatus AgcA caused lowered azole susceptibility (27). They additionally demonstrated that AgcA localized in mitochondria (27). As shown in slc25a12-deficient mice, the malate-aspartate NADH shuttle activity in mitochondria was significantly impaired, resulting in decreased mitochondrial NADH (28). In the mitochondrial matrix, NADH is the donor of electrons transferred to ubiquinone in complex I (NADH oxidoreductase). As reported by Bowyer et al. (29) and Bromley et al. (30), the disruption of the 29.9-kDa subunit in complex I affected azole susceptibility. For that reason, agcA disruption might represent a similar effect of subunit disruption by a decrease in NADH in mitochondria, although further investigation is necessary.

In A. fumigatus, UbcD has not been characterized, although the homologs in S. cerevisiae (Ubc4p) have been studied, and Ubc4, which is a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2, has been studied in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (31). In S. pombe, Ubc4 cleaved Sre2, a sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) (32). Fungal SREBPs are involved in adaptation under hypoxic conditions. The cleavage of SREBP promotes adaptation to the environment, such as conditions of hypoxia (33). The proteins SrbA and SrbB, two homologous SREBPs of A. fumigatus, regulate ergosterol biosynthesis, azole susceptibility, and hypoxic adaptation. The SREBP-deficient strains showed decreased expression of some genes in the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway, including the cyp51A gene (34, 35). A plausible mechanism of the azole tolerance led by the T98K mutation is that UbcD constitutively activated the function as a ubiquitin ligase, which in turn activated SREBP proteins. If this mechanism is supported, then an increased expression level of cyp51A can be expected. However, the expression of cyp51A was not higher in TBCZ34 than in the parental strain (Fig. S2). Generally, the ubiquitin system broadly affects various pathways in an organism, suggesting that the mutation affects protein degradation and cleavage in multiple pathways. The effects of the mutation at the 98th residue remain unresolved.

A mutation in abcJ co-occurred with the ubcD mutation. The abcJ gene encodes an ABC transporter. Many ABC transporters are also reported as factors involved in azole resistance (reviewed by Pérez-Cantero et al. [36]). Although the mutation was not found in clinical or environmental strains, nonsense mutations were observed in a clinical isolate, A. fumigatus strain IFM 58401 (37). The MIC of VRCZ was 1 μg/ml, which was equal to the MIC90 value among 69 strains (21). The contribution of AbcJ to azole tolerance remains unknown. Further studies must be conducted to elucidate the relation between AbcJ and azole tolerance.

Homologs of the rttA gene were conserved broadly among Aspergillus spp. Homologous proteins of some Aspergillus spp., such as Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus clavatus, and Aspergillus nidulans, included the C6 zinc finger domain. The C6 zinc finger motif is found in transcription factors like AtrR in A. fumigatus. AtrR is an essential factor for azole resistance in A. fumigatus (38). However, RttA in A. fumigatus impairs the domain (Fig. S3). The amino acid sequence following the C6 zinc finger motif is also conserved among homologous proteins and is registered in the Pfam database as PF11951, but the function of the domain remains unknown. As shown in a data set provided by Bowyer et al. (https://fungidb.org/fungidb/app/record/dataset/DS_9afe38853e) on FungiDB (21), the transcripts of rttA were increased twice to three times under the presence of itraconazole.

Ren et al. (18) and Cui et al. (19) reported that Cyp51A mutations and TR introduction occurred by TBCZ selection. However, there were no controls to show that the strains obtained were truly progeny of the parental strains used for the experiments. Snelders et al. reported that the in vitro selection of A. fumigatus strain TR34 with 8 μg/ml tebuconazole obtained a strain with a triplicate of the 34-bp region after three passages (39). We were able to follow the progeny in this study using pyrG deletion, and the TR mutations were not induced during the selection. As shown by Zhang et al., sexual reproduction might be important for the acquisition of additional TRs (16). Therefore, selection using each mating type might be effective to introduce a TR in a cyp51A promoter.

In summary, by in vitro selection with TBCZ, we ultimately obtained no TBCZ-adapted isolates. Furthermore, we identified mutations in MfsD, AgcA, AbcJ, UbcD, and RttA that might contribute to azole tolerance. These genes are novel players in contributions to azole tolerance, although their roles remain unknown. Further studies are expected to be useful to elucidate the azole tolerance mechanism in A. fumigatus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

A. fumigatus strains used for this study are shown in Tables 1 and 2 and Tables S2 and S3. Potato dextrose agar, Aspergillus minimal medium (MM) (40), and MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)-buffered RPMI 1640 were used for culturing the strains. When using uracil auxotrophs, 10 mM uracil was added to the appropriate medium.

Selective passaging with TBCZ.

In this study, we used an A. fumigatus ΔpyrG strain as the parental strain because we could distinguish it from other A. fumigatus strains and contaminants. In the initial selection round, A. fumigatus ΔpyrG (105 conidia) was inoculated into MOPS-buffered RPMI 1640 with 10 mM uracil and 1/2 MIC of TBCZ (0.5 μg/ml). It was cultured at 35°C for 7 to 10 days at 130 rpm. After culturing, the fungal cells that were recovered were spread on three plates containing different concentrations of TBCZ and the top 10 colonies in each selection round were picked up. After isolation, spore suspensions of each isolate were prepared and stocked at −80°C until further use. For the next selection round, isolates were mixed and the MIC of TBCZ against the mixture was determined. We conducted three selection rounds. The 1/2 MICs of TBCZ were 2 and 8 μg/ml in the second and third rounds, respectively.

MIC measurement.

The MICs of ITCZ, VRCZ, PSCZ, and AMPH were found using the broth microdilution method based on CLSI M38-A2 (41, 42). Except for PSCZ, dry plate Eiken (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used for the experiments. PSCZ (Merck, KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at 0.2 mg/ml and used. For uracil auxotrophs, uracil at 10 mM as the final concentration was added to MOPS-buffered RPMI 1640. The MICs were determined at 48 h after inoculation.

Genome sequencing and detecting mutated points.

A. fumigatus strains were cultured in potato dextrose broth with 0.1% yeast extract and 10 mM uracil. After culturing at 35°C for 20 h, mycelia were recovered (Miracloth; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Kits (Quick-DNA fungal/bacterial; Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) were used for genome DNA preparation. We performed whole-genome sequencing using next-generation methods, as described in an earlier report (6). In brief, we prepared a fragmented DNA library using a NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA library preparation kit for Illumina according to the manufacturer’s instructions (New England Biolabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). Sequencing in paired-end 2 × 150-bp mode on a HiSeq X system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was done by BGI Japan (Kobe, Japan). For single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling, we mapped the reads to the genome sequence of A. fumigatus reference strain Af293 (29,420,142 bp; genome version s03-m04-r03) (43, 44) using Burroughs-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) version 0.7.15-r1142 (45). Then, we identified SNPs using SAMtools version 1.8 (37, 46) and filtered them with >10-fold coverage, >30 mapping quality, and 75% consensus using in-house scripts (47, 48). We annotated the functional effect of SNPs with SnpEff version 4.1 l (49). The data obtained were deposited in DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number DRA011933.

Sanger sequencing.

Sanger sequencing was performed as described elsewhere (50).

Gene disruption and replacement.

DNA fragment preparation by fusion PCR and transformation by protoplasting were done as described in an earlier report (51). Primers used for this study are shown in Table S1. 5-Fluoroorotic acid was used for the selection of the ΔpyrG strain (Fig. S4). A cassette containing a hygromycin resistance gene was used to select hygromycin-resistant transformants (Fig. S5 and S6) (52). To revert the ubcD mutation in TBCZ34, we replaced the gene with the wild-type ubcD and a hygromycin resistance gene (Fig. S7). Correct replacements and disruptions were confirmed using PCR.

Quantification of cyp51A expression.

Amounts of 104 conidia of A. fumigatus ΔpyrG and TBCZ34 were inoculated into MOPS-buffered RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10 mM uracil and cultured at 35°C for 48 h. After cultivation, fungal cells were recovered and washed twice with sterilized water. After the cells were frozen and dried using a vacuum freeze dryer (FDU-1200; Tokyo Rikakikai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), the dried cells were disrupted with zirconia beads and a Disruptor Genie (Scientific Industries, Inc., Bohemia, NY, USA). Total RNA was prepared with Isogen II (Nippon Gene Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Reverse transcription was performed using ReverTra Ace quantitative PCR (qPCR) reverse transcription (RT) master mix with genomic DNA (gDNA) remover (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Thunderbird SYBR qPCR mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd.) and a LightCycler were used for the quantification of cyp51A expression with primer pair 5′-ACAGAACCGCCAATGGTCTT-3′ and 5′-CGCCATACTTTTCTCTGCACG-3′. The β-actin gene was used as a reference housekeeping gene for the experiment (53). The relative expression level of cyp51A was analyzed using REST software (54).

Statistics.

Comparisons of colony diameters were analyzed for statistical significance using the two-tailed Student’s t test for paired comparisons or one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s test for post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons.

Data availability.

The sequencing data obtained were deposited in DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number DRA011933.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by AMED under grants number JP19fm0208024 and JP20jm0110015.

We thank Kasumi Kodama for her technical assistance. We acknowledge DBCLS TogoTV for providing images used in this presentation of our work.

T.T., D.H., A.W., and H.T. participated in the study design. T.T., K.O., and M.S. conducted the experiments of selective passaging with TBCZ, Sanger sequencing, and gene disruption and replacement. Y.K. and H.T. conducted genome sequencing and detection of mutated points. T.T. prepared the draft manuscript. T.T., D.H., A.W., and H.T. mainly reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We declare that we have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele RO, Denning DW. 2017. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases—estimate precision. J Fungi (Basel) 3:57. 10.3390/jof3040057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baddley JW, Andes DR, Marr KA, Kontoyiannis DP, Alexander BD, Kauffman CA, Oster RA, Anaissie EJ, Walsh TJ, Schuster MG, Wingard JR, Patterson TF, Ito JI, Williams OD, Chiller T, Pappas PG. 2010. Factors associated with mortality in transplant patients with invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis 50:1559–1567. 10.1086/652768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kosmidis C, Denning DW. 2015. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax 70:270–277. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagiwara D, Arai T, Takahashi H, Kusuya Y, Watanabe A, Kamei K. 2018. Non-cyp51A azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolates with mutation in HMG-CoA reductase. Emerg Infect Dis 24:1889–1897. 10.3201/eid2410.180730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toyotome T, Fujiwara T, Kida H, Matsumoto M, Wada T, Komatsu R. 2016. Azole susceptibility in clinical and environmental isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus from eastern Hokkaido, Japan. J Infect Chemother 22:648–650. 10.1016/j.jiac.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagiwara D, Takahashi H, Watanabe A, Takahashi-Nakaguchi A, Kawamoto S, Kamei K, Gonoi T. 2014. Whole-genome comparison of Aspergillus fumigatus strains serially isolated from patients with aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 52:4202–4209. 10.1128/JCM.01105-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu H, Chen W, Li L, Wan Z, Li R, Liu W. 2010. Clinical itraconazole-resistant strains of Aspergillus fumigatus, isolated serially from a lung aspergilloma patient with pulmonary tuberculosis, can be detected with real-time PCR method. Mycopathologia 169:193–199. 10.1007/s11046-009-9249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Hirano K, Ide S, Mihara T, Hosogaya N, Takazono T, Morinaga Y, Nakamura S, Kurihara S, Imamura Y, Miyazaki T, Nishino T, Tsukamoto M, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, Yanagihara K, Yasuoka A, Tashiro T, Kohno S. 2012. Correlation between triazole treatment history and susceptibility in clinically isolated Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4870–4875. 10.1128/AAC.00514-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballard E, Melchers WJG, Zoll J, Brown AJP, Verweij PE, Warris A. 2018. In-host microevolution of Aspergillus fumigatus: a phenotypic and genotypic analysis. Fungal Genet Biol 113:1–13. 10.1016/j.fgb.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ballard E, Weber J, Melchers WJG, Tammireddy S, Whitfield PD, Brakhage AA, Brown AJP, Verweij PE, Warris A. 2019. Recreation of in-host acquired single nucleotide polymorphisms by CRISPR-Cas9 reveals an uncharacterised gene playing a role in Aspergillus fumigatus azole resistance via a non-cyp51A mediated resistance mechanism. Fungal Genet Biol 130:98–106. 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagiwara D. 2018. Current status of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolates in East Asia. Med Mycol J 59:E71–E76. 10.3314/mmj.18.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen P, Liu J, Zeng M, Sang H. 2020. Exploring the molecular mechanism of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. J Mycol Med 30:100915. 10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.100915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraczek MG, Bromley M, Buied A, Moore CB, Rajendran R, Rautemaa R, Ramage G, Denning DW, Bowyer P. 2013. The cdr1B efflux transporter is associated with non-cyp51a-mediated itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1486–1496. 10.1093/jac/dkt075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gsaller F, Hortschansky P, Furukawa T, Carr PD, Rash B, Capilla J, Müller C, Bracher F, Bowyer P, Haas H, Brakhage AA, Bromley MJ. 2016. Sterol biosynthesis and azole tolerance is governed by the opposing actions of SrbA and the CCAAT binding complex. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005775. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verweij PE, Snelders E, Kema GH, Mellado E, Melchers WJ. 2009. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a side-effect of environmental fungicide use? Lancet Infect Dis 9:789–795. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Snelders E, Zwaan BJ, Schoustra SE, Meis JF, van Dijk K, Hagen F, van der Beek MT, Kampinga GA, Zoll J, Melchers WJG, Verweij PE, Debets AJM. 2017. A novel environmental azole resistance mutation in Aspergillus fumigatus and a possible role of sexual reproduction in its emergence. mBio 8:e00791-17. 10.1128/mBio.00791-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verweij PE, Chowdhary A, Melchers WJG, Meis JF. 2016. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: can we retain the clinical use of mold-active antifungal azoles? Clin Infect Dis 62:362–368. 10.1093/cid/civ885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren J, Jin X, Zhang Q, Zheng Y, Lin D, Yu Y. 2017. Fungicides induced triazole-resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus associated with mutations of TR46/Y121F/T289A and its appearance in agricultural fields. J Hazard Mater 326:54–60. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui N, He Y, Yao S, Zhang H, Ren J, Fang H, Yu Y. 2019. Tebuconazole induces triazole-resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus in liquid medium and soil. Sci Total Environ 648:1237–1243. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, van den Heuvel J, Debets AJM, Verweij PE, Melchers WJG, Zwaan BJ, Schoustra SE. 2017. Evolution of cross-resistance to medical triazoles in Aspergillus fumigatus through selection pressure of environmental fungicides. Proc Biol Sci 284:20170635. 10.1098/rspb.2017.0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basenko E, Pulman J, Shanmugasundram A, Harb O, Crouch K, Starns D, Warrenfeltz S, Aurrecoechea C, Stoeckert C, Kissinger J, Roos D, Hertz-Fowler C. 2018. FungiDB: an integrated bioinformatic resource for fungi and oomycetes. J Fungi 4:39. 10.3390/jof4010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.da Silva Ferreira ME, Capellaro JL, dos Reis Marques E, Malavazi I, Perlin D, Park S, Anderson JB, Colombo AL, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Goldman MHS, Goldman GH. 2004. In vitro evolution of itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus involves multiple mechanisms of resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:4405–4413. 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4405-4413.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meneau I, Coste AT, Sanglard D. 2016. Identification of Aspergillus fumigatus multidrug transporter genes and their potential involvement in antifungal resistance. Med Mycol 54:616–627. 10.1093/mmy/myw005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavero S, Vozza A, Del Arco A, Palmieri L, Villa A, Blanco E, Runswick MJ, Walker JE, Cerdán S, Palmieri F, Satrústegui J. 2003. Identification and metabolic role of the mitochondrial aspartate-glutamate transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol 50:1257–1269. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmieri L, Pardo B, Lasorsa FM, Del Arco A, Kobayashi K, Iijima M, Runswick MJ, Walker JE, Saheki T, Satrústegui J, Palmieri F. 2001. Citrin and aralar1 are Ca2+-stimulated aspartate/glutamate transporters in mitochondria. EMBO J 20:5060–5069. 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satrústegui J, Contreras L, Ramos M, Marmol P, del Arco A, Saheki T, Pardo B. 2007. Role of aralar, the mitochondrial transporter of aspartate-glutamate, in brain N-acetylaspartate formation and Ca(2+) signaling in neuronal mitochondria. J Neurosci Res 85:3359–3366. 10.1002/jnr.21299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song J, Liu X, Zhai P, Huang J, Lu L. 2016. A putative mitochondrial calcium uniporter in A. fumigatus contributes to mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and stress responses. Fungal Genet Biol 94:15–22. 10.1016/j.fgb.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jalil MA, Begum L, Contreras L, Pardo B, Iijima M, Li MX, Ramos M, Marmol P, Horiuchi M, Shimotsu K, Nakagawa S, Okubo A, Sameshima M, Isashiki Y, Del Arco A, Kobayashi K, Satrústegui J, Saheki T. 2005. Reduced N-acetylaspartate levels in mice lacking aralar, a brain- and muscle-type mitochondrial aspartate-glutamate carrier. J Biol Chem 280:31333–31339. 10.1074/jbc.M505286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowyer P, Mosquera J, Anderson M, Birch M, Bromley M, Denning DW. 2012. Identification of novel genes conferring altered azole susceptibility in Aspergillus fumigatus. FEMS Microbiol Lett 332:10–19. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bromley M, Johns A, Davies E, Fraczek M, Mabey Gilsenan J, Kurbatova N, Keays M, Kapushesky M, Gut M, Gut I, Denning DW, Bowyer P. 2016. Mitochondrial complex I is a global regulator of secondary metabolism, virulence and azole sensitivity in fungi. PLoS One 11:e0158724. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seufert W, Jentsch S. 1990. Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes UBC4 and UBC5 mediate selective degradation of short-lived and abnormal proteins. EMBO J 9:543–550. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheung R, Espenshade PJ. 2013. Structural requirements for sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) cleavage in fission yeast. J Biol Chem 288:20351–20360. 10.1074/jbc.M113.482224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes AL, Todd BL, Espenshade PJ. 2005. SREBP pathway responds to sterols and functions as an oxygen sensor in fission yeast. Cell 120:831–842. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chung D, Barker BM, Carey CC, Merriman B, Werner ER, Lechner BE, Dhingra S, Cheng C, Xu W, Blosser SJ, Morohashi K, Mazurie A, Mitchell TK, Haas H, Mitchell AP, Cramer RA. 2014. ChIP-seq and in vivo transcriptome analyses of the Aspergillus fumigatus SREBP SrbA reveals a new regulator of the fungal hypoxia response and virulence. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004487. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagiwara D, Watanabe A, Kamei K. 2016. Sensitisation of an azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strain containing the Cyp51A-related mutation by deleting the SrbA gene. Sci Rep 6:38833. 10.1038/srep38833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pérez-Cantero A, López-Fernández L, Guarro J, Capilla J. 2020. Azole resistance mechanisms in Aspergillus: update and recent advances. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55:105807. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi-Nakaguchi A, Muraosa Y, Hagiwara D, Sakai K, Toyotome T, Watanabe A, Kawamoto S, Kamei K, Gonoi T, Takahashi H. 2015. Genome sequence comparison of Aspergillus fumigatus strains isolated from patients with pulmonary aspergilloma and chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis. Med Mycol 53:353–360. 10.1093/mmy/myv003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paul S, Stamnes M, Thomas GH, Liu H, Hagiwara D, Gomi K, Filler SG, Moye-Rowley WS. 2019. AtrR is an essential determinant of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. mBio 10:e02563-18. 10.1128/mBio.02563-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snelders E, Camps SMT, Karawajczyk A, Schaftenaar G, Kema GHJ, van der Lee HA, Klaassen CH, Melchers WJG, Verweij PE. 2012. Triazole fungicides can induce cross-resistance to medical triazoles in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS One 7:e31801. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill TW, Kafer E. 2001. Improved protocols for Aspergillus minimal medium: trace element and minimal medium salt stock solutions. Fungal Genet Rep 48:20–21. 10.4148/1941-4765.1173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toyotome T, Saito S, Koshizaki Y, Komatsu R, Matsuzawa T, Yaguchi T. 2020. Prospective survey of Aspergillus species isolated from clinical specimens and their antifungal susceptibility: a five-year single-center study in Japan. J Infect Chemother 26:321–323. 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.CLSI. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi; approved standard—2nd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nierman WC, Pain A, Anderson MJ, Wortman JR, Kim HS, Arroyo J, Berriman M, Abe K, Archer DB, Bermejo C, Bennett J, Bowyer P, Chen D, Collins M, Coulsen R, Davies R, Dyer PS, Farman M, Fedorova N, Fedorova N, Feldblyum TV, Fischer R, Fosker N, Fraser A, García JL, García MJ, Goble A, Goldman GH, Gomi K, Griffith-Jones S, Gwilliam R, Haas B, Haas H, Harris D, Horiuchi H, Huang J, Humphray S, Jiménez J, Keller N, Khouri H, Kitamoto K, Kobayashi T, Konzack S, Kulkarni R, Kumagai T, Lafton A, Latgé JP, Li W, Lord A, Lu C, et al. 2005. Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature 438:1151–1156. 10.1038/nature04332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnaud MB, Cerqueira GC, Inglis DO, Skrzypek MS, Binkley J, Chibucos MC, Crabtree J, Howarth C, Orvis J, Shah P, Wymore F, Binkley G, Miyasato SR, Simison M, Sherlock G, Wortman JR. 2012. The Aspergillus Genome Database (AspGD): recent developments in comprehensive multispecies curation, comparative genomics and community resources. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D653–D659. 10.1093/nar/gkr875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25:2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suzuki S, Horinouchi T, Furusawa C. 2014. Prediction of antibiotic resistance by gene expression profiles. Nat Commun 5:5792. 10.1038/ncomms6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tenaillon O, Rodriguez-Verdugo A, Gaut RL, McDonald P, Bennett AF, Long AD, Gaut BS. 2012. The molecular diversity of adaptive convergence. Science 335:457–461. 10.1126/science.1212986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Land SJ, Lu X, Ruden DM. 2012. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff:: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin) 6:80–92. 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Toyotome T, Hamada S, Yamaguchi S, Takahashi H, Kondoh D, Takino M, Kanesaki Y, Kamei K. 2019. Comparative genome analysis of Aspergillus flavus clinically isolated in Japan. DNA Res 26:95–103. 10.1093/dnares/dsy041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szewczyk E, Nayak T, Oakley CE, Edgerton H, Xiong Y, Taheri-Talesh N, Osmani SA, Oakley BR, Oakley B. 2006. Fusion PCR and gene targeting in Aspergillus nidulans. Nat Protoc 1:3111–3120. 10.1038/nprot.2006.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wnendt S, Jacobs M, Stahl U. 1990. Transformation of Aspergillus giganteus to hygromycin B resistance. Curr Genet 17:21–24. 10.1007/BF00313244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cramer RA, Gamcsik MP, Brooking RM, Najvar LK, Kirkpatrick WR, Patterson TF, Balibar CJ, Graybill JR, Perfect JR, Abraham SN, Steinbach WJ. 2006. Disruption of a nonribosomal peptide synthetase in Aspergillus fumigatus eliminates gliotoxin production. Eukaryot Cell 5:972–980. 10.1128/EC.00049-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. 2002. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 30:e36. 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental figures and tables. Download AAC.02657-20-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.7 MB (689KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing data obtained were deposited in DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number DRA011933.