Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the prevalence and quantity of aortic valve calcium (AVC) in two large cohorts, stratified according to age and lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)), and to assess the association between Lp(a) and AVC.

Methods

We included 2412 participants from the population-based Rotterdam Study (52% women, mean age=69.6±6.3 years) and 859 apparently healthy individuals from the Amsterdam University Medical Centers (UMC) outpatient clinic (57% women, mean age=45.9±11.6 years). All individuals underwent blood sampling to determine Lp(a) concentration and non-enhanced cardiac CT to assess AVC. Logistic and linear regression analyses were performed to investigate the associations of Lp(a) with the presence and amount of AVC.

Results

The prevalence of AVC was 33.1% in the Rotterdam Study and 5.4% in the Amsterdam UMC cohort. Higher Lp(a) concentrations were independently associated with presence of AVC in both cohorts (OR per 50 mg/dL increase in Lp(a): 1.54 (95% CI 1.36 to 1.75) in the Rotterdam Study cohort and 2.02 (95% CI 1.19 to 3.44) in the Amsterdam UMC cohort). In the Rotterdam Study cohort, higher Lp(a) concentrations were also associated with increase in aortic valve Agatston score (β 0.19, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.32 per 50 mg/dL increase).

Conclusions

Lp(a) is robustly associated with presence of AVC in a wide age range of individuals. These results provide further rationale to assess the effect of Lp(a) lowering interventions in individuals with early AVC to prevent end-stage aortic valve stenosis.

Keywords: aortic valve stenosis, multidetector computed tomography, hyperlipidaemias

Introduction

Aortic valve stenosis (AVS) is the most prevalent form of valvular heart disease in developed countries.1 It is characterised by a long asymptomatic period during which lipid accumulation followed by inflammation and microcalcification of the valve leaflets gradually progress. A second stage of accelerated macrocalcification may lead to clinically overt AVS, which ultimately requires surgical or transcatheter valve replacement.2

Evidence of a causal role of lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) in the pathogenesis of AVS has rapidly accumulated over the past decade.3 4 This insight, combined with the advent of therapeutic agents capable of reducing the Lp(a) concentration up to 90%,5 opens avenues for preventive strategies in individuals with elevated Lp(a) and early-stage aortic valve disease.

Non-enhanced CT is a sensitive technique to detect early-stage aortic valve calcium (AVC), which precedes the onset of symptomatic AVS by many years.6–8 Previous data show robust associations between Lp(a) and CT-assessed AVC.9 10 Here, we expand on these findings by describing the prevalence of AVC stratified by age and Lp(a) concentration in two large Dutch cohorts. Furthermore, we investigated whether age acted as an effect modifier on the relationship between Lp(a) and AVC presence and quality.

Methods

Study population

This study leverages two large cohorts in whom information on Lp(a) and AVC was available. The Rotterdam Study is a population-based cohort study aimed at investigating determinants of age-related diseases in 15 000 persons aged 40 years and over.11 Between 2003 and 2006, a random sample of participants were invited to undergo a non-contrast multidetector CT scan to visualise AVC, as part of a larger project on vascular calcification. A total of 2524 participants were scanned. The Rotterdam Study has been entered into the Netherlands National Trial Register (www.trialregister.nl) and into the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/network/primary/en/) under shared catalogue number NTR6831. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study and have their information obtained from treating physicians.

From the perspective of AVS prevention, we extended our study towards younger individuals by including a second cohort, consisting of 859 apparently healthy individuals who were screened at the Amsterdam University Medical Centers (UMC) outpatient clinic for familial premature (non-valvular) cardiovascular disease between July 2009 and April 2016. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. During their visit, a complete medical history was taken and clinical parameters were obtained for all individuals. Full study procedures for both cohorts have been described previously.12 13

Assessment and quantification of AVC

In the Rotterdam Study, non-enhanced cardiac CT was performed using a 16-slice or 64-slice CT scanner (Somatom Sensation 16 or 64; Siemens, Forchheim, Germany). Consecutive non-overlapping 3 mm thick slices were acquired within a single breath hold and reconstructed with 12 mm × 1.5 mm collimation, 120 kVp, effective 30 mAs and prospective ECG triggering at 50% of the cardiac cycle. Images were reconstructed with 3 mm effective slice width and 1.5 mm reconstruction interval. Reconstructions were performed with 180 mm field-of-view and medium sharp convolution kernel (B35f). In the Amsterdam UMC cohort, coronary CT scans were acquired on a third-generation dual-source CT scanner (Somatom Force, Siemens). Image acquisition parameters were set at a voltage of 120 kV and current of 80 mAs for coronary artery calcium (CAC) analysis. Standard reconstructed slice thickness was 3 mm with a 1.5 mm increment and using a Qr36 kernel in a mediastinal window/level setting of 400/60. For both cohorts, valvular and coronary artery calcium were quantified using Agatston methodology by experienced readers blinded to clinical parameters.8 14 Presence of AVC was defined as an aortic valve Agatston score >0.

Lp(a) measurements

In the Rotterdam Study, fasting blood samples were collected during the fourth study visit. Plasma was isolated and immediately put on ice and stored at −80°C. In the Amsterdam UMC cohort, serum was collected in 5 mL BD Vacutainer SST II Plus plastic serum tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, New Jersey, USA). Blood was centrifuged for 5 min at 1900 g at 20°C after clotting to obtain serum, which was stored in cryovials at –80°C. In both cohorts, Lp(a) was measured on a Cobas 8000 analyser using the KIV-2 number independent Randox immunoassay (Randox Laboratories, UK) with an Lp(a) concentration range of 0–187 mg/dL.15

Measurement of covariates

Information regarding relevant cardiovascular risk factors (body mass index (BMI), smoking, blood pressure, lipid panel) was assessed by interview, physical examination or blood sampling, according to previously described methodology for both cohorts.12 13

Statistical analysis

All results are primarily shown for the cohorts separately and secondarily for the pooled cohort. Baseline characteristics are depicted as mean±SD for normally distributed continuous variables, median (IQR) for non-normally distributed continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical variables. In addition to analyses on Lp(a) as a continuous measure, we stratified Lp(a) into four groups: <50th percentile, between 50th and 79th percentile, between 80th and 94th percentile, and ≥95th percentile, based on commonly used clinical cut-off values.16 We determined the prevalence of AVC in different age groups, each spanning a 5-year interval, between 45 and 80 years of age.

The primary objective was to study the relationship between Lp(a) concentration (both as a continuous variable and according to the abovementioned categories) and the presence of AVC. We performed logistic regression, both uncorrected (model 1) and corrected for age and sex (model 2), including BMI, smoking status, non-high-density lipoprotein (non-HDL) cholesterol and use of antihypertensive medication (model 3), and finally including CAC (model 4). ORs were computed per 50 mg/dL increase in Lp(a) concentration for continuous analyses and per Lp(a) group using Lp(a) <50th percentile as a reference for categorical analyses. Additionally, we determined the prevalence of AVC in those with Lp(a) below and above the 80th percentile, stratified by 10-year spanning intervals between ages 45 and 75.

The secondary study objective was to assess the relationship between Lp(a) and the amount of AVC (Agatston score) in individuals with prevalent AVC, using linear regression, with similar models to those mentioned above. To this end, we used a log-transformed Agatston score (LN(agatston)). As exploratory analyses, we determined whether age and sex acted as effect modifiers on the relationship between Lp(a) and AVC. Missing data percentages were 0.2% for BMI, 1.1% for use of antihypertensive medication and 2.0% for smoking. CAC score was missing in 0.3% of cases due to previous stenting procedures or pacemaker insertion. No data were missing for either Lp(a) or presence of AVC. Little’s missing completely at random test showed that BMI, use of antihypertensive medication and smoking status were missing at random, which were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations. We created 25 imputed copies of the original data set, of which the estimates from the regression analyses were pooled. All statistical analyses were performed with R V.3.6.3 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). Imputations were performed using the MICE package. Figures were constructed using GraphPad Prism V.8.3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA).

Patient and public involvement

Participants were not involved in determining the research question or outcome measures, nor were they involved in recruitment, design or implementation of the study. Participants were not asked for advice on the interpretation of results.

Results

Baseline characteristics and age-stratified prevalence of AVC

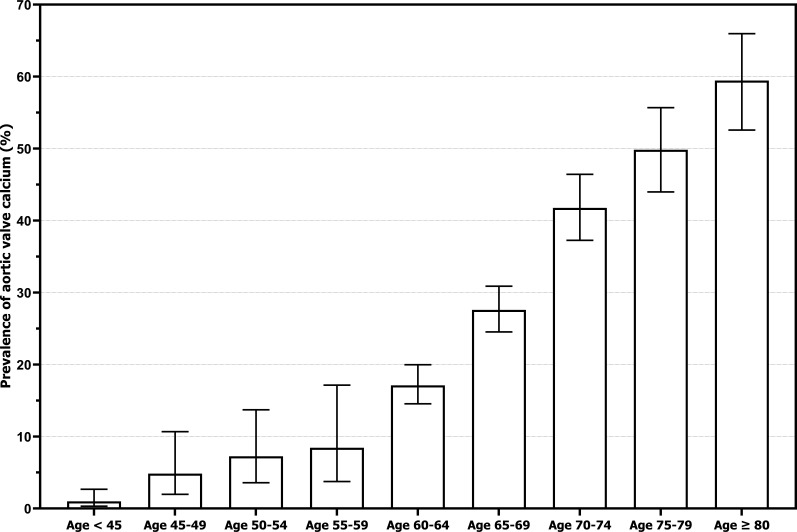

The baseline characteristics for the two separate cohorts are listed in table 1. The Rotterdam Study cohort had a mean age of 69.6±6.7 years (range 60–98 years), and the Amsterdam UMC cohort had a mean age of 45.9±11.6 years (range 24–75 years). There were fewer current smokers in the Rotterdam Study (15.1% vs 22.5%), but more participants using antihypertensive medication (40% vs 17.3%). Other risk factors were equally distributed between cohorts. Figure 1 portrays the pooled prevalence of AVC per 5-year increase in age, ranging from 1.0% for individuals <45 years, up to 59.4% in those ≥80 years. As expected, subjects with AVC were older, more often male, had higher BMI, used antihypertensive medication more frequently and had higher Lp(a) concentrations compared with subjects without AVC (online supplemental table 1). The 80th Lp(a) percentile was 47.7 mg/dL and the 95th Lp(a) percentile was 88.7 mg/dL after combining the two cohorts. Out of the 844 participants with AVC, 244 (28.9%) had Lp(a) concentrations ≥80th percentile and 73 (8.7%) had Lp(a) concentrations ≥95th percentile.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Rotterdam Study cohort (n=2412) | Amsterdam UMC cohort (n=859) | Combined cohort (N=3271) | |

| Age (years) | 69.6±6.7 | 46.3±11.8 | 63.3±13.3 |

| Female (%) | 1247 (51.7) | 488 (56.8) | 1735 (53.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6±3.9 | 26.5±4.4 | 27.4±4.1 |

| Smoking (current) | 365 (15.1) | 193 (22.5) | 558 (17.1) |

| Use of antihypertensive medication (%) | 964 (40.0) | 149 (17.3) | 1113 (34.0) |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.2±1.0 | 3.9±1.1 | 4.1±1.0 |

| Lipoprotein(a) (mg/dL) | 12.5 (5.4–37.4) | 12.6 (5.3–35.2) | 12.5 (5.3–36.7) |

| Presence of aortic valve calcification (%) | 798 (33.1) | 46 (5.4) | 844 (25.8) |

Data are depicted as mean±SD, median (IQR) or number (percentage).

Data are original, non-imputed values.

BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; UMC, University Medical Centers.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of aortic valve calcium stratified by age. Aortic valve calcium was defined as an aortic valve Agatston score >0. The prevalence of aortic valve calcium was 4 of 406 (1.0%) for ages below 45, 6 of 124 (4.8%) for ages 45–49, 9 of 124 (7.3%) for ages 50–54, 7 of 83 (8.4%) for ages 55–59, 132 of 772 (17.1%) for ages 60–64, 218 of 790 (27.6%) for ages 65–69, 193 of 462 (41.8%) for ages 70–74, 146 of 293 (49.8%) for ages 75–79, and 129 of 217 (59.4%) for ages 80 and over. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

heartjnl-2021-319044supp001.pdf (14.6KB, pdf)

Lp(a) and presence of AVC

The associations between Lp(a) and AVC in the Rotterdam Study and Amsterdam UMC cohort are depicted separately in table 2. In the Rotterdam Study, higher Lp(a) concentrations showed a significant relationship with presence of AVC, independent of age, sex, BMI, smoking, use of antihypertensive medication and non-HDL cholesterol: OR 1.54 (95% CI 1.36 to 1.75) per 50 mg/dL increase in Lp(a). In the younger Amsterdam UMC cohort, the effect size of Lp(a) was similar: OR 1.98 (95% CI 1.16 to 3.37) for every 50 mg/dL increase in Lp(a). When stratified to Lp(a) percentile, individuals from the Rotterdam Study between the 80th and 94th Lp(a) percentile and ≥95th Lp(a) percentile had an OR of 1.85 (95% CI 1.43 to 2.40) and 2.93 (95% CI 1.94 to 4.43) for AVC, respectively. Those between the 50th and 79th Lp(a) percentile did not show increased AVC prevalence (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.23). These findings were similar in the Amsterdam UMC cohort, in which individuals between the 80th and 94th Lp(a) percentile more often had AVC (OR 3.36, 95% CI 1.43 to 7.89), as did those ≥95th Lp(a) percentile (OR 3.45, 95% CI 1.17 to 10.16). Adding CAC to the AVC model did not alter the observed effect size of Lp(a) in either cohort.

Table 2.

Association between lipoprotein(a) and presence of aortic valve calcium: separate cohorts

| Rotterdam Study cohort Presence of AVC | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Lp(a), per 50 mg/dL increase | 1.44 (1.28 to 1.61) | 1.56 (1.38 to 1.76) | 1.54 (1.36 to 1.75) | 1.53 (1.34 to 1.73) |

| Lp(a) categories | ||||

| <50th percentile (<12.5 mg/dL) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 50th–79th percentile (12.5–51.4 mg/dL) | 1.04 (0.85 to 1.27) | 1.02 (0.83 to 1.26) | 0.99 (0.80 to 1.23) | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.19) |

| 80th–94th percentile (51.4–96.6 mg/dL) | 1.78 (1.40 to 2.27) | 1.85 (1.43 to 2.40) | 1.85 (1.42 to 2.40) | 1.81 (1.39 to 2.36) |

| ≥95th percentile (>96.6 mg/dL) | 2.39 (1.64 to 3.49) | 3.04 (2.02 to 4.58) | 2.92 (1.93 to 4.42) | 2.93 (1.91 to 4.50) |

|

Amsterdam UMC cohort

Presence of AVC | ||||

| Lp(a), per 50 mg/dL increase | 2.17 (1.31 to 3.60) | 2.12 (1.25 to 3.58) | 2.02 (1.19 to 3.44) | 2.09 (1.23 to 3.55) |

| Lp(a) categories | ||||

| <50th percentile (<12.6 mg/dL) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 50th–79th percentile (12.6–42.4 mg/dL) | 1.46 (0.69 to 3.13) | 1.21 (0.55 to 2.65) | 1.21 (0.55 to 2.65) | 1.12 (0.50 to 2.49) |

| 80th–94th percentile (42.4–74.3 mg/dL) | 2.83 (1.29 to 6.21) | 3.15 (1.38 to 7.18) | 3.15 (1.38 to 7.18) | 3.24 (1.40 to 7.48) |

| ≥95th percentile (>74.3 mg/dL) | 4.48 (1.64 to 12.22) | 3.66 (1.27 to 10.51) | 3.66 (1.27 to 10.51) | 3.46 (1.18 to 10.15) |

Data are presented as OR with 95% CI.

Model 1 is unadjusted. Model 2 is adjusted for age and sex. Model 3 adds body mass index, use of antihypertensive medication, smoking and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Model 4 adds coronary artery calcification.

AVC, aortic valve calcium; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); UMC, University Medical Centers.

Lp(a) and valvular calcific burden

In individuals with established calcification, Lp(a) as a continuous variable was not associated with valvular Agatston score in the Amsterdam UMC cohort. In the Rotterdam Study, there was a significant association between increasing Lp(a) levels and the Agatston score of the aortic valve (β 0.19, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.32 for each 50 mg/dL increase in Lp(a)) (table 3). This effect seemed to be driven by those with extremely high Lp(a) levels (≥95th percentile), who had significantly higher valvular Agatston scores compared with participants below the 50th Lp(a) percentile (β 0.57, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.97).

Table 3.

Association between Lp(a) and aortic valve calcific burden: separate cohorts

| Rotterdam Study cohort Aortic valve Agatston score (ln) | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Lp(a), per 50 mg/dL increase | 0.16 (0.03 to 0.29) | 0.21 (0.08 to 0.34) | 0.19 (0.06 to 0.32) | 0.19 (0.06 to 0.32) |

| Lp(a) categories | ||||

| <50th percentile (<12.5 mg/dL) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 50th–79th percentile (12.5–51.4 mg/dL) | −0.10 (−0.35 to 0.16) | −0.09 (−0.35 to 0.16) | −0.18 (−0.44 to 0.08) | −0.19 (−0.45 to 0.07) |

| 80th–94th percentile (51.4–96.6 mg/dL) | 0.161 (−0.13 to 0.46) | 0.20 (−0.09 to 0.16) | 0.13 (−0.16 to 0.42) | 0.13 (−0.16 to 0.42) |

| ≥95th percentile (>96.6 mg/dL) | 0.424 (−0.00 to 0.85) | 0.60 (0.18 to 0.49) | 0.57 (0.17 to 0.97) | 0.54 (0.15 to 0.94) |

|

Amsterdam UMC cohort

Aortic valve Agatston score | ||||

| Lp(a), per 50 mg/dL increase | −0.12 (−1.11 to 0.88) | −0.17 (−1.09 to 0.90) | 0.01 (−1.05 to 1.07) | −0.02 (−1.09 to 1.05) |

| Lp(a) categories | ||||

| <50th percentile (<12.6 mg/dL) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 50th–79th percentile (12.6–42.4 mg/dL) | 0.74 (−0.75 to 2.23) | 1.08 (−0.26 to 2.42) | 1.00 (−0.42 to 2.41) | 0.96 (−0.51 to 2.42) |

| 80th–94th percentile (42.4–74.3 mg/dL) | 0.93 (−0.59 to 2.45) | 0.55 (−0.74 to 1.84) | 0.78 (−0.62 to 2.18) | 0.75 (−0.70 to 2.20) |

| ≥95th percentile (>74.3 mg/dL) | −0.59 (−2.47 to 1.30) | −1.29 (−3.90 to 1.32) | −1.03 (−3.96 to 1.90) | −1.01 (−3.99 to 1.97) |

Data are presented as beta coefficients with 95% CI.

Model 1 is unadjusted. Model 2 is adjusted for age and sex. Model 3 adds body mass index, use of antihypertensive medication, smoking and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Model 4 adds coronary artery calcification.

Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); UMC, University Medical Centers.

Lp(a) compared with other risk factors for AVC

After observing that the distribution and effect size of Lp(a) and the prevalence of AVC were comparable between the Rotterdam Study and the Amsterdam UMC cohort, we combined these data at the individual participant level to assess how the effect size of Lp(a) compares with that of other known risk factors for AVC. Table 4 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis, demonstrating that the OR for AVC in individuals with Lp(a) ≥95th percentile (OR 2.84, 95% CI 1.96 to 4.10) was comparable with a 10-year increase in age (OR 2.93, 95% CI 2.61 to 3.28), and much larger than for male sex (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.70 to 2.45), BMI per kg/m2 increase (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.06), active smoking (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.86), use of antihypertensive medication (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.51) and non-HDL cholesterol per mmol/L increase (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.19). The OR for Lp(a) levels between the 80th and 94th percentile was 1.89 (95% CI 1.48 to 2.42). As a sensitivity analysis, we added the cohort (Rotterdam Study or Amsterdam UMC) as a variable to the logistic regression analysis to assess whether the study centre was acting as a confounder, but this was not significantly associated with the outcome (p=0.20) and did not change the results of the analysis.

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis for presence of AVC: combined cohorts

| Variable | OR for AVC | P value |

| Lipoprotein(a) group | ||

| <50th percentile (<12.5 mg/dL) | Reference | |

| 50th–79th percentile (12.5–47.7 mg/dL) | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.21) | 0.853 |

| 80th–94th percentile (47.7–88.7 mg/dL) | 1.89 (1.48 to 2.42) | <0.001 |

| ≥95th percentile (>88.7 mg/dL) | 2.84 (1.96 to 4.10) | <0.001 |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 2.93 (2.61 to 3.28) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 2.04 (1.70 to 2.45) | <0.001 |

| BMI (per kg/m2 increase) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.06) | 0.003 |

| Smoking (active) | 1.45 (1.14 to 1.86) | 0.003 |

| Use of antihypertensive medication | 1.25 (1.03 to 1.51) | 0.022 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (per mmol/L increase) | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.19) | 0.092 |

Data are presented as OR with 95% CI.

AVC, aortic valve calcium; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

Age and sex do not modify the effect of Lp(a) on AVC

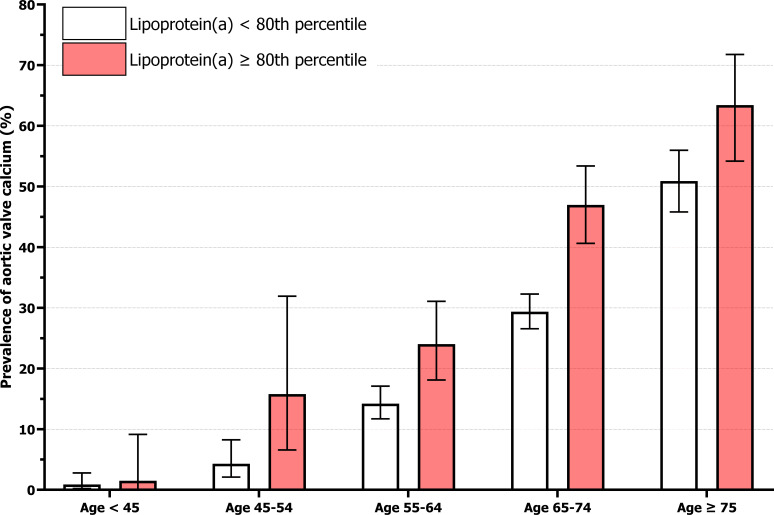

The prevalence of AVC stratified by age and Lp(a) is depicted in figure 2. Strikingly, the prevalence of AVC in those above the 80th Lp(a) percentile was comparable with 10-year-older individuals below the 80th percentile for nearly all age groups. In individuals above and below the 80th Lp(a) percentile, respectively, AVC prevalence was 1.5% vs 0.9% in those <45 years, 15.8% vs 4.3% between 45 and 54 years, 24.0% vs 14.2% between 55 and 64 years, 47.0% vs 29.4% between 65 and 74 years, and 63.4% vs 50.9% in those ≥75 years of age. Age was not a significant effect modifier on the association between Lp(a) and presence of AVC (p=0.89), nor was sex (p=0.53).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of aortic valve calcium stratified by age and lipoprotein(a). Aortic valve calcium was defined as an aortic valve Agatston score >0. The prevalence of aortic valve calcium for lipoprotein(a) above and below the 80th percentile (47.7 mg/dL), respectively, was 1 of 67 (1.5%) vs 3 of 339 (0.9%) for ages below 45, 6 of 38 (15.8%) vs 9 of 210 (4.3%) for ages 45–54, 43 of 179 (24.0%) vs 96 of 676 (14.2%) for ages 55–64, 116 of 247 (47.0%) vs 295 of 1005 (29.4%) for ages 65–74, and 78 of 123 (63.4%) vs 197 of 387 (50.9%) for ages 75 and over. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

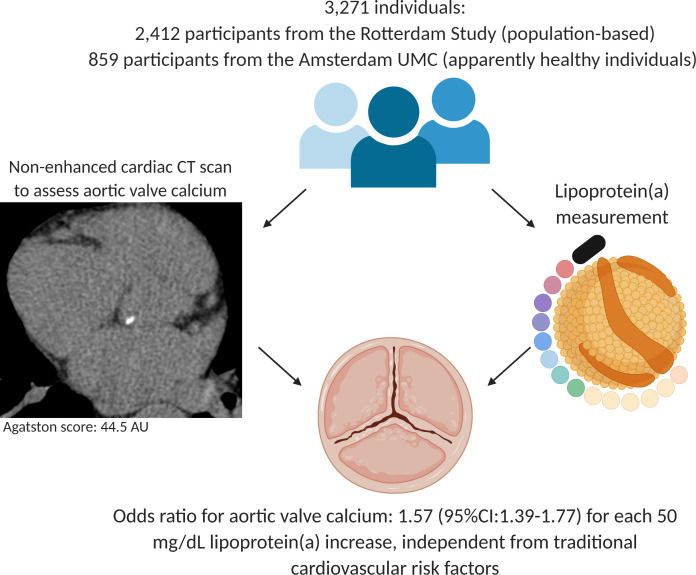

Our study demonstrates that Lp(a) is robustly associated with AVC, independent of age, sex and known risk factors for AVC. Additional adjustment for CAC, reflecting the global atherosclerotic burden, did not alter the relation between Lp(a) and AVC (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Individuals with elevated lipoprotein(a) levels have a significantly increased prevalence of aortic valve calcium, independent from age, sex, body mass index, smoking, use of antihypertensive medication, and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. UMC, University Medical Centers; AU, Agatston units.

CT imaging has previously been used in large cohort studies to identify individuals with AVC. Here, we report a 33.1% prevalence of AVC in the population-based Rotterdam Study cohort with a mean age of 69.6 years. This is in line with population cohorts of similar age, such as the Framingham Heart Study (39%), the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (43%), and with a slightly younger cohort from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (16%), taking into account the differences in age and ethnicity.9 17 By extending the cohort with individuals from the Amsterdam UMC cohort, we were able to add important insights into the prevalence of AVC in younger age categories. In individuals between 45 and 54 years of age above the 80th Lp(a) percentile, the prevalence of AVC was already 15.8%. Importantly, we observed an almost identical association of Lp(a) with AVC in both cohorts included in the current study. This implies that Lp(a) is equally important in younger individuals, stressing both the importance and opportunities of early diagnosis.

Lp(a) is considered to play a role during both the initiation and progression phase of AVS. However, as calcium begets calcium, Lp(a) lowering is less likely to abrogate the accelerated calcification phase towards clinically overt AVS.18 This notion is in line with previous trials which found low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) lowering with statins and/or ezetimibe to be an unsuccessful strategy to attenuate AVS progression,19–21 despite LDL-C being implicated in the development of AVS. Namely, a recent post-hoc subanalysis of the Simvastatin and Ezetimibe in Aortic Stenosis (SEAS) trial indicated that simvastatin/ezetimibe seemed to impede aortic jet velocity progression in a subgroup of patients with mild stenosis and high baseline LDL-C levels, whereas those who already had moderate stenosis and low baseline LDL-C did not benefit.22 Similarly, we envision that those with elevated Lp(a) would benefit most from Lp(a) lowering at earlier stages of AVC.

We show that the individuals with Lp(a) concentrations above the 80th percentile are characterised by a vastly increased prevalence of AVC from a young age. It may be hypothesised that the prolonged presence of AVC in these individuals predisposes to progression to end-stage AVS, supported by an association between Lp(a) and AVC quantity in the current study. Moreover, previous imaging studies using sodium fluoride indeed showed that asymptomatic patients with AVS with higher Lp(a) are characterised by increased active valvular calcification, more progression on follow-up echocardiography and CT, and more valve-related events.23 24 With Lp(a) lowering therapies on the horizon, timing of intervention in those who would benefit most is crucial. CT imaging might be a promising method to screen asymptomatic individuals with high Lp(a) for the presence of AVC, the earliest discernible disease stage of AVS. Such a cohort would provide an ideal testing ground to assess whether Lp(a) lowering therapy can delay or prevent end-stage aortic valve disease. As 28.9% of individuals with AVC are characterised by elevated Lp(a) concentrations (≥80th percentile, corresponding to approximately 50 mg/dL), more than one in four individuals with AVC may benefit from Lp(a) lowering treatment.

The strengths of our study include the large sample size and the CT-based assessment of AVC. Specifically, the fact that we were able to include two cohorts and thereby present data over a wide age range from 24 to 98 years is unique and important in light of the development of preventive strategies for AVS. However, this study also has some limitations that deserve consideration. First, although the Amsterdam UMC cohort consists of apparently healthy individuals, they were selected based on a positive family history of premature atherosclerosis. However, the gradual increase in AVC prevalence over age suggests no meaningful inconsistency between the included cohorts. Second, three different CT scanners were used to assess the presence of AVC. To address this issue, we used standardised protocols for the acquisition of coronary calcium scans, which should make the variance between different scanners negligible. Third, participants did not undergo echocardiography, which made us unable to account for valve morphology in our analysis. Fourth, triglycerides were not measured, precluding the possibility to calculate the LDL-C concentration. Accordingly, we corrected for non-HDL cholesterol in our analyses. Finally, as this was a cross-sectional study, we were unable to determine any causality between Lp(a) and AVC.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that Lp(a) is robustly associated with AVC in two large Dutch cohorts of asymptomatic individuals. Screening high-risk individuals above the 80th Lp(a) percentile (≥50 mg/dL) for AVC with CT imaging could be a fruitful approach to select individuals for randomised trials, to assess whether Lp(a) reduction can delay or prevent end-stage AVS.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Aortic valve calcium (AVC) is the earliest discernible stage of aortic valve disease.

Studies suggesting a causal role of lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) in the aetiology of AVC are accumulating.

Large-scale data on age-stratified and Lp(a)-stratified prevalence and quantity of AVC remain scarce.

What might this study add?

Lp(a) is strongly associated with the presence of AVC.

In those with AVC, Lp(a) correlates with increased calcific burden.

AVC is already highly prevalent in younger individuals with Lp(a) above the 80th percentile, emphasising the need for early identification.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

CT imaging might be a fruitful method to detect early AVC in high-risk individuals with elevated Lp(a), who might benefit most from Lp(a) lowering therapies.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Zheng_KH

Contributors: YK: study concept and design, statistical analysis, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript. SSS, MK, MV: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript. KHZ, RV: study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript. S-JP: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript. ES: analysis and interpretation of data, funding acquisition, critical revision of the manuscript. MB: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript. YBdR: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, funding acquisition, critical revision of the manuscript. ESGS, DB: supervision, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, funding acquisition, critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: The Rotterdam Study is supported by Erasmus MC and Erasmus University Rotterdam; the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research; the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw); the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly; the Netherlands Genomics Initiative; the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science; the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport; European Commission; and the Municipality of Rotterdam. YK and ESGS were supported by the Netherlands Heart Foundation (CVON 2017-20: generating the best evidence-based pharmaceutical targets for atherosclerosis (GENIUS II)).

Competing interests: SSS, YBdR and ES were supported by Amgen: Lp(a) Ahead Study. ESGS has received research grants/support to his institution from Amgen, Sanofi, Resverlogix and Athera, and has served as a consultant for Amgen, Sanofi, Esperion, Novartis and Ionis Pharmaceuticals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The Rotterdam Study has been approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus MC. The Amsterdam UMC study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

References

- 1.Lindman BR, Clavel M-A, Mathieu P, et al. Calcific aortic stenosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16006. 10.1038/nrdp.2016.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iung B, Vahanian A. Degenerative calcific aortic stenosis: a natural history. Heart 2012;98:iv7–13. 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamstrup PR, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated lipoprotein(a) and risk of aortic valve stenosis in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:470–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arsenault BJ, Boekholdt SM, Dubé M-P, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels, genotype, and incident aortic valve stenosis: a prospective Mendelian randomization study and replication in a case-control cohort. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2014;7:304–10. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsimikas S, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Gouni-Berthold I, et al. Lipoprotein(a) reduction in persons with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2020;382:244–55. 10.1056/NEJMoa1905239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2739–91. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pawade T, Clavel M-A, Tribouilloy C, et al. Computed tomography aortic valve calcium scoring in patients with aortic stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;11:e007146. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bos D, Bozorgpourniazi A, Mutlu U, et al. Aortic valve calcification and risk of stroke: the Rotterdam study. Stroke 2016;47:2859–61. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thanassoulis G, Campbell CY, Owens DS, et al. Genetic associations with valvular calcification and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2013;368:503–12. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao J, Steffen BT, Budoff M, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels are associated with subclinical calcific aortic valve disease in white and black individuals: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2016;36:1003–9. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikram MA, Brusselle GGO, Murad SD, et al. The Rotterdam study: 2018 update on objectives, design and main results. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:807–50. 10.1007/s10654-017-0321-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vliegenthart R, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, et al. Coronary calcification improves cardiovascular risk prediction in the elderly. Circulation 2005;112:572–7. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.488916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verweij SL, de Ronde MWJ, Verbeek R, et al. Elevated lipoprotein(a) levels are associated with coronary artery calcium scores in asymptomatic individuals with a family history of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Clin Lipidol 2018;12:597–603. 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;15:827–32. 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsimikas S, Fazio S, Ferdinand KC, et al. NHLBI working group recommendations to reduce lipoprotein(a)-mediated risk of cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:177–92. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsimikas S. A test in context: lipoprotein(a): diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:692–711. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens DS, Katz R, Takasu J, et al. Incidence and progression of aortic valve calcium in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Cardiol 2010;105:701–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng KH, Tzolos E, Dweck MR. Pathophysiology of aortic stenosis and future perspectives for medical therapy. Cardiol Clin 2020;38:1–12. 10.1016/j.ccl.2019.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowell SJ, Newby DE, Prescott RJ, et al. A randomized trial of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in calcific aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2389–97. 10.1056/NEJMoa043876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossebø AB, Pedersen TR, Boman K, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with simvastatin and ezetimibe in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1343–56. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chan KL, Teo K, Dumesnil JG, et al. Effect of lipid lowering with rosuvastatin on progression of aortic stenosis: results of the aortic stenosis progression observation: measuring effects of rosuvastatin (ASTRONOMER) trial. Circulation 2010;121:306–14. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.900027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greve AM, Bang CN, Boman K, et al. Effect modifications of lipid-lowering therapy on progression of aortic stenosis (from the simvastatin and ezetimibe in aortic stenosis [SEAS] study). Am J Cardiol 2018;121:739–45. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capoulade R, Yeang C, Chan KL, et al. Association of mild to moderate aortic valve stenosis progression with higher lipoprotein(a) and oxidized phospholipid levels: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3:1212–7. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng KH, Tsimikas S, Pawade T, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and oxidized phospholipids promote valve calcification in patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2150–62. 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

heartjnl-2021-319044supp001.pdf (14.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.