Abstract

Persistent ill health after acute COVID-19—referred to as long COVID, the post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, or the post-COVID-19 condition—has emerged as a major concern. We undertook an international consensus exercise to identify research priorities with the aim of understanding the long-term effects of acute COVID-19, with a focus on people with pre-existing airways disease and the occurrence of new-onset airways disease and associated symptoms. 202 international experts were invited to submit a minimum of three research ideas. After a two-phase internal review process, a final list of 98 research topics was scored by 48 experts. Patients with pre-existing or post-COVID-19 airways disease contributed to the exercise by weighting selected criteria. The highest-ranked research idea focused on investigation of the relationship between prognostic scores at hospital admission and morbidity at 3 months and 12 months after hospital discharge in patients with and without pre-existing airways disease. High priority was also assigned to comparisons of the prevalence and severity of post-COVID-19 fatigue, sarcopenia, anxiety, depression, and risk of future cardiovascular complications in patients with and without pre-existing airways disease. Our approach has enabled development of a set of priorities that could inform future research studies and funding decisions. This prioritisation process could also be adapted to other, non-respiratory aspects of long COVID.

Introduction

The emergence and rapid spread of COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, has led to about 180 million confirmed cases and nearly 4 million deaths worldwide as of June 19, 2021.1 The acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection results in a range of clinical presentations, from asymptomatic infection to severe illness requiring hospital admission and intensive care.2 Factors associated with increased risk of infection and severe disease include, but are not limited to, age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.3, 4 The presence of pre-existing comorbidities, especially pre-existing respiratory disease, is also a major risk factor for severe outcomes.5

There is already a high global burden of existing, non-COVID-19-related airways disease: 300–400 million people worldwide are living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),6 and the burden is broadly similar for asthma, which has an increasing global prevalence and affects about 10% of the population in high-income countries.7 Furthermore, individuals with COPD have an increased risk of hospital admission and death from COVID-19.8 Mild and moderate asthma has generally not been associated with increased risk of COVID-19-related hospital admission and mortality,9 although individuals with asthma who have required oral steroids in the preceding year have had increased risk of mortality in acute COVID-19.3, 5

In addition to acute illness, COVID-19 can result in long-term morbidity and a prolonged recovery period.10 This post-acute phase of COVID-19 (now widely known as long COVID, the post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, or the post-COVID-19 condition) has been reported in patients admitted to hospital with severe COVID-19,10 as well as in children and adults who initially experienced mild disease.10, 11, 12, 13 In the UK, approximately one in five people are estimated to have COVID-19 symptoms beyond 5 weeks, and one in ten report symptoms persisting for 12 weeks or more.14 As a disease that affects multiple body systems, long COVID can result in wide-ranging symptoms, including breathlessness, chest pain, fatigue, muscle weakness, impaired cognition, anxiety, and depression.10 Studies in the non-COVID-19 literature indicate that the prevalence of many of these symptoms—eg, anxiety, fatigue, and cognitive impairment—is increased in people with airways disease (panel 1 ).6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 However, whether these symptoms are more common or more severe in patients with pre-existing airways disease after acute COVID-19 illness is uncertain. Similarly, the underlying mechanisms of these chronic health sequelae of COVID-19, particularly in relation to pre-existing and newly developed airways disease, are unkown.10, 23

Panel 1. Symptoms reported in people with long COVID and their presence in patients with airways disease.

Several persistent symptoms that have been reported after acute COVID-1910, 11, 12, 13, 15 are also present in patients with chronic airways disease. By contrast, other post-acute symptoms are not well described in airways diseases. Examples are listed below.

Associated with airways disease

Not associated with airways disease

To address these uncertainties and improve long-term health outcomes related to COVID-19, the Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 study (PHOSP-COVID) consortium was established. PHOSP-COVID is a UK national multidisciplinary consortium of clinicians and data and basic scientists aiming to create an integrated research and clinical platform to investigate the multidimensional long-term health outcomes in patients who have been admitted to hospital with COVID-19. Within this consortium, expert subgroups have been established, including a working group on airways disease, bronchiolitis, and bronchiectasis (the PHOSP-COVID Airways Diseases Working Group) who commissioned this priority-setting initiative. We sought to identify research priorities to understand the long-term consequences of acute COVID-19, with a focus on airways disease (pre-existing and newly developed after COVID-19), to guide researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and funding organisations to address the burden of long COVID globally.

Key messages.

Rationale and approach

-

•

Patients with pre-existing airways disease are thought to be at higher risk of developing serious outcomes from acute COVID-19, and new incident cases of airways disease have been reported after acute COVID-19 illness

-

•

Many of the described symptoms in long COVID are commonly reported in patients with airways disease in non-COVID-19 studies; given the emergence of this new disease entity, we sought to identify airways-related research priorities for long COVID

-

•

Using the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI) prioritisation method, 300 research ideas were proposed by participants, including international experts in airways disease and clinicians tackling long COVID

-

•

After a two-phase internal review process, a final list of 98 research ideas was scored by 48 participants according to five predefined criteria: answerability, feasibility, timeliness, effect on burden reduction, and equity; scores were also weighted through input from patients who had been admitted to hospital with COVID-19 in association with pre-existing airways disease or who had developed airways disease after acute COVID-19

Priorities for research

-

•

A list of the 20 highest-ranking research ideas was developed using the experts' scores and patients' input; the top priority was the investigation of the relationship between prognostic scores (using the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infections Consortium 4C Mortality Score) at hospital admission and morbidity at 3 months and 12 months after hospital discharge in patients with and without pre-existing airways disease

-

•

High scores were also assigned to research ideas to investigate the differences between patients with and without airways disease in relation to the prevalence and severity of post-COVID-19 fatigue, sarcopenia, anxiety, depression, and risk of future cardiovascular complications; to understand predictors of hospital readmission; to develop and validate tools for remote monitoring of symptoms; to determine the incidence of and risk factors for new-onset symptomatic obstructive airways disease; to assess the clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of exercise rehabilitation in patients with airways disease; and to investigate risk of venous thrombotic events and outcomes with anticoagulation treatment

Implications

-

•

Identification of research priorities to advance understanding of the long-term effects of COVID-19 in the context of airways disease is vital at a time when resources are limited and rapid answers are needed

-

•

The CHNRI process could be readily adapted to develop research priorities in other respiratory and non-respiratory disease areas relevant to COVID-19 care

Methods

Overview of the CHNRI method

We adapted the Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI) method, which was originally developed for setting research priorities for global child health, to our priority-setting exercise for long COVID in the context of airways disease. The CHNRI method uses the principle of crowdsourcing to independently generate research ideas from a large group of experts, and scores these against a predefined set of criteria. It is a systematic, transparent, and democratic approach that has been used in more than 100 exercises led by national governments (eg, in China, India, and South Africa), funders (eg, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), and multilateral organisations, including WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund. The aim of those exercises was to set research priorities in areas ranging from the reduction of global child mortality, non-communicable diseases, or disability to the efficient execution of national health plans.24, 25, 26, 27 The main advantages of the CHNRI method include: its systematic nature; transparency and replicability; clearly defined context and criteria; involvement of funders, stakeholders, and policy makers; a structured way of obtaining information; informative and intuitive quantitative outputs; assessment of the level of agreement for each proposed research idea; and independent scoring by many experts, thus limiting the influence of individuals on the rest of the group.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 The quantitative output of the CHNRI method as applied here is based on the collective input of a large group of experts in airways disease. As a result of this process, clinicians, academics, funders, and policy makers can clearly visualise the strengths, weaknesses, and relative rankings of each proposed research topic.

Establishment of expert groups

In September 2020, a subgroup of the PHOSP-COVID Airways Diseases Working Group (LGH, ADS, AS, IR, OE, LD, KP, and DA) established the Expert Management Group. This group defined the aims and context of the prioritisation exercise and drafted guidelines for the application of the CHNRI method to research priorities for airways disease in long COVID. This included defining the final criteria, the approach to scoring, and the timelines, coordinating the steps of the priority-setting exercise, and inviting experts.

Revised guidelines for the CHNRI method, based on experience of its use, have recently been published.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 The CHNRI approach involves the selection of experts according to their research impact in previous years. However, as studies of COVID-19 were just emerging in the published literature when the Expert Management Group was established, we used two main approaches to identify international experts. First, experts who contributed to recently completed CHNRI-based prioritisation exercises on asthma or COPD were invited to participate. Their opinions were relevant because their research already focused on chronic airways disease. They were identified in the previous CHNRI exercises through searches of the Web of Science for the most productive authors in the preceding 5-year period or for lead authors (first, last, or corresponding authors) of the top 1% most cited research articles in the relevant area of study. Second, experts were invited from other established research groups working on airways disease and COVID-19, including the PHOSP-COVID consortium and the remainder of the PHOSP-COVID Airways Diseases Working Group, the Severe Asthma Registry Network, the UK Bronchiectasis Network and Biobank, and the International Primary Care Respiratory Group. After excluding duplicate names, a total of 202 experts were identified and invited to participate. Each expert was invited to submit a minimum of three priority research ideas or topics related to COVID-19 and airways disease.

Scoring of research ideas

In the first phase of internal review by the Expert Management Group, submitted research ideas were checked for clarity and to ensure that they met the purpose of the study. The final list of research topics was consolidated during the second phase of review, which involved refining the submitted ideas to clearly identify the new knowledge that would be generated through the proposed research. Topics with a high degree of overlap were merged. Research subthemes were identified from the consolidated list. The experts were then invited to systematically rank the final list of research ideas using five predefined criteria: answerability, feasibility, timeliness, effect on burden reduction, and equity (panel 2 ). Experts were offered four response options for scoring: 0 (unlikely to meet the criterion); 0·5 (informed, but not sure whether it can meet the criterion); 1 (likely to meet the criterion); or left blank if the expert felt insufficiently informed to make a judgment.

Panel 2. Predefined context for setting research priorities and criteria for scoring.

The context

-

•

Population of interest: the research priorities will apply to patients admitted to hospital for COVID-19 who had pre-existing airways disease or who developed airways disease after COVID-19

-

•

Disease, disability, and death burden: the research priorities will focus on the long-term consequences of airways disease in COVID-19 survivors with a form of the disease that required hospital admission

-

•

Geographical limits: the findings from this priority-setting exercise should have global relevance

-

•

Timescale: the results of the proposed research ideas should be available or ready to implement within 3 years

-

•

Preferred style of investing: the research priorities identified should guide investment strategy in health research with funding distributed across the various research directions with different levels of investment risk and feasibility

Criteria for scoring

-

•

Answerability: is the research idea likely to be answerable, using the proposed study design?

-

•

Feasibility: is the research idea feasible, given the required inputs, facilities, equipment, and personnel?

-

•

Timeliness: is the research idea likely to be answered within the timeframe specified in the context?

-

•

Burden: is the research idea likely to lead to a substantial reduction of the burden specified in the context?

-

•

Equity: is the research idea likely to lead to interventions or changes in practice that will favour patients equally?

The context and criteria for scoring were defined according to recommendations from previous Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative exercises and guidelines.32, 33

Data analysis

All completed scoresheets from the experts were collated into a final worksheet. First, all entries were checked for consistency and errors by the Expert Management Group. Intermediate scores were then computed for each criterion as the sum of the scores (ie, 1, 0·5, or 0) across the criteria divided by the total number of answers received. The answers that were left blank were not included in the denominator. The overall research priority score (RPS) for each idea was computed as the mean of the scores across the five criteria. Thus, the RPS could theoretically range between 0% and 100% for each scored research idea.

To give insight into the level of agreement among all the scorers, we computed the average expert agreement (AEA). This provides an indicator of the average proportion of scoring experts who gave the most common answer when scoring a particular research idea, expressed as:

where 5 represents the five criteria and N is the total number of experts.

Patient input and weighting

In addition to the experts' scoring, we extended aspects of the exercise to patients who had been admitted to hospital with acute COVID-19 or were experiencing long COVID (including individuals with pre-existing airways disease and individuals who had developed a new airways disease after treatment for COVID-19). To account for patients' views, we developed weights for the selected criteria using a method already established by the CHNRI for involving stakeholders.31 We contacted patients through the Asthma UK and British Lung Foundation Partnership, a UK-based national charity that aims to foster improvements in outcomes for people affected by lung diseases. We used an online survey to recruit and screen patients. The purpose, context, and criteria specific to this exercise were explained to the patients, who then answered the question: “Which of the criteria (ie, answerability, feasibility, timeliness, burden, equity) do you consider most important to set research priorities for COVID-19 in airways diseases?” The resulting weights were expressed as a percentage and applied to each criterion. This resulted in a weighted RPS, defined by the following equation:

where RPSn and w n are the RPS and weights for each of the five criteria, respectively.

Results

Research ideas, themes, and scoring

Among the 202 experts contacted, 88 (44%) accepted the invitation and 59 (29%) contributed research ideas after the CHNRI process had been explained to them. Over a 4-week period, we received 300 research ideas from experts. After the two-phase internal review process by the Expert Management Group, 165 duplicate or unclear ideas were removed and 27 were merged (appendix 1 pp 2–4). Ten research ideas were excluded because they were considered to be out of scope or could not be addressed within the context of PHOSP-COVID research.

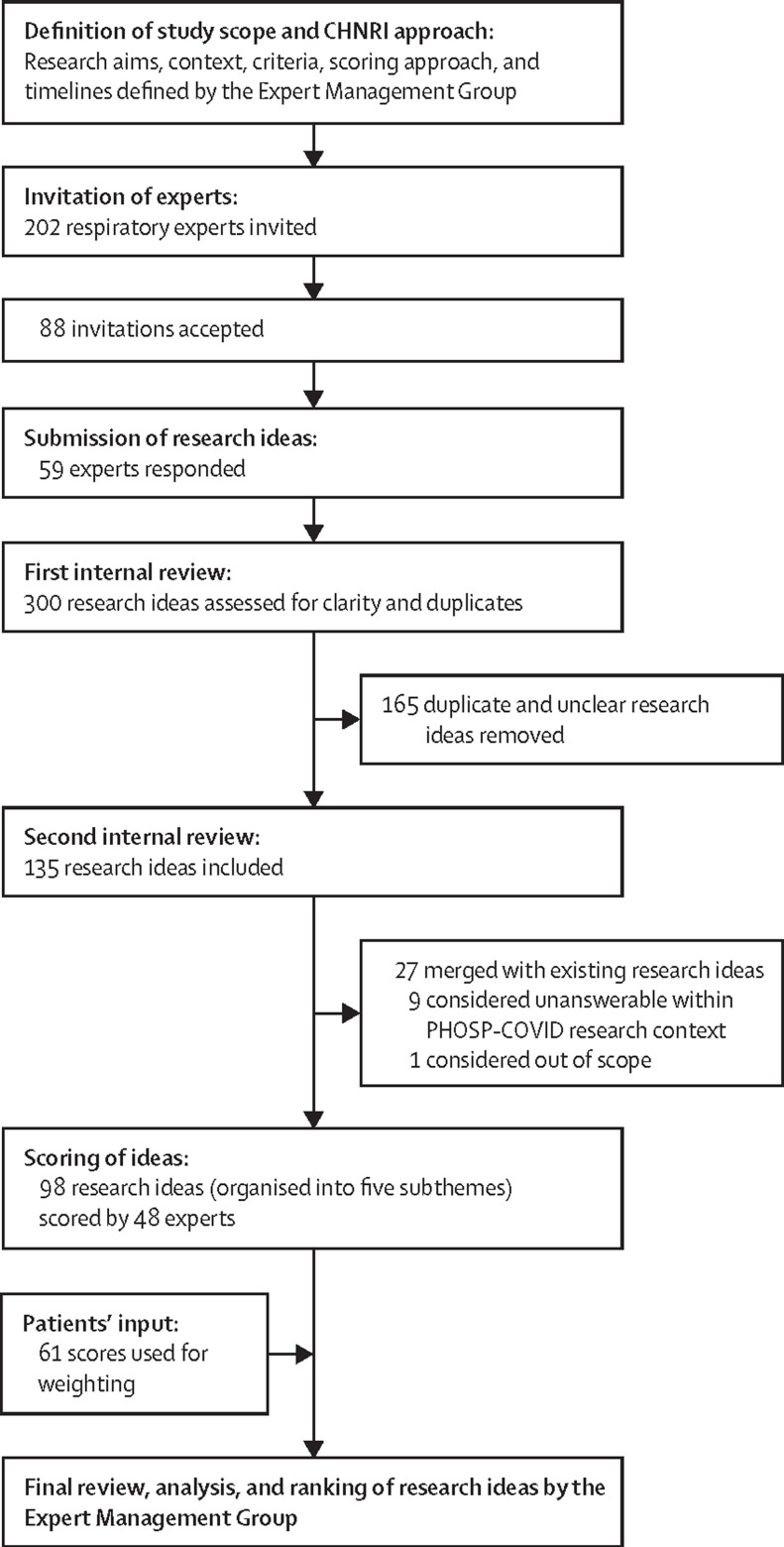

The final list of 98 research ideas was organised into five subthemes and sent back to the contributing experts for scoring. The subthemes were: (1) study of associations with or risk factors for the development or exacerbation of airways disease in COVID-19 survivors (36 research ideas); (2) understanding of the role of interventions for COVID-19 on the short-term and long-term outcomes of people with chronic airways disease (22 research ideas); (3) investigation of the long-term physiological effects and disease burden of COVID-19 in patients with chronic airways disease (21 research ideas); (4) investigation of the long-term effects of COVID-19 on quality of life, mental health, and social characteristics in patients with chronic airways disease (6 research ideas); and (5) development of innovative approaches to health care and policy-making initiatives targeting patients with chronic airways disease (13 research ideas). These subthemes were systematically ranked by 48 experts (55% of the 88 participants who accepted the invitation) who returned completed scoresheets within 4 weeks. The process for the CHNRI priority-setting exercise is summarised in the figure .

Figure.

Process for setting research priorities

CHNRI=Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative. PHOSP-COVID=Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 study.

Overall research priority score

The overall RPS for each of the 98 research ideas ranged from 0·339 to 0·864. The AEA ranged from 0·417 to 0·846, with a median of 0·683. There was a high degree of agreement among experts on the most highly-ranked research ideas, with the AEA decreasing with decreasing RPS (r=0·9334, p<0·001). The 98 ranked research ideas, with RPS and AEA data, are presented in appendix 1 (pp 5–15) and appendix 2 (sheets 6, 7).

Of the 20 highest-ranked research ideas, half (including five of the ten highest scoring ideas) were on subtheme 1—ie, identification of associations with or risk factors for developing or worsening airways disease in COVID-19 survivors (table 1 ). The three highest scoring research ideas involved comparing morbidity after hospital discharge between COVID-19 survivors with and without pre-existing airways disease, with the first (RPS 0·864, AEA 0·838) focusing on the correlation between prognostic scores—using the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infections Consortium (ISARIC) 4C Mortality Score,34 a risk stratification score used to predict in-hospital mortality for patients with COVID-19—at hospital admission and post-discharge morbidity at 3 months and 12 months in the two groups. The second highest-ranked priority (RPS 0·852, AEA 0·846) was assessment of the extent of post-COVID-19 fatigue, sarcopenia, anxiety, and depression. The third (RPS 0·849, AEA 0·817) was investigation of the risk of future cardiovascular complications in patients treated for severe COVID-19. The ten highest priorities included research ideas relating to hospital admission and symptoms in patients with pre-existing airways disease, such as understanding predictors of hospital readmission and validating tools for remote monitoring of symptoms. Other topics among the ten highest scoring ideas were specific to patients with obstructive airways disease who had COVID-19, including determining the incidence of and risk factors for new-onset airways disease, recovery of current smokers with COPD, and clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of exercise rehabilitation. Research ideas to explore the risk of venous thromboembolic events in patients with COVID-19, including estimation of the incidence of pulmonary embolism and study of the effects of treatment with anticoagulants on outcomes of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19, were among the 20 highest-ranking research topics.

Table 1.

20 highest-ranked research ideas according to their overall RPS and AEA

| Research idea | Subtheme | Answerability | Feasibility | Timeliness | Burden | Equity | RPS | AEA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Investigation of the correlation between prognostic scores using the ISARIC 4C Mortality Score* at hospital admission and morbidity at 3 months and 12 months after hospital discharge in patients with and without pre-existing airways disease | 1 | 1·00 | 1·00 | 0·98 | 0·56 | 0·78 | 0·864 | 83·8 |

| 2 | Assessment of whether 3-month and 6-month post-COVID-19 fatigue, sarcopenia, anxiety, and depression scores are worse in patients with pre-existing airways disease than in those without pre-existing airways disease, and whether any difference is significant when adjusted for severity of in-patient disease | 1 | 0·96 | 0·91 | 0·96 | 0·66 | 0·77 | 0·852 | 84·6 |

| 3 | Investigation of whether patients treated for acute COVID-19 with pre-existing airways disease are at higher risk of future cardiovascular complications (eg, myocardial infarction or stroke at 6 months and 12 months after hospital discharge) than those without pre-existing airways disease | 3 | 0·95 | 0·90 | 0·94 | 0·65 | 0·81 | 0·849 | 81·7 |

| 4 | Identification of the predictors of hospital readmission after COVID-19 in patients with pre-existing airways disease compared with those without pre-existing airways disease | 1 | 0·93 | 0·88 | 0·89 | 0·71 | 0·83 | 0·847 | 83·3 |

| 5 | Development and validation of tools for remote monitoring of symptoms, and for self-monitoring of symptoms, especially in patients with pre-existing airways disease | 5 | 0·89 | 0·88 | 0·90 | 0·76 | 0·78 | 0·841 | 82·1 |

| 6 | Investigation of the incidence of and risk factors for new-onset symptomatic obstructive airways disease after COVID-19, defined clinically or with objective diagnostic tests (eg, spirometry and CT imaging at 3 months and 12 months after hospital discharge) | 1 | 0·97 | 0·91 | 0·91 | 0·64 | 0·77 | 0·840 | 80·8 |

| 7 | Assessment of whether recovery from severe COVID-19 pneumonia is worse for current smokers with COPD than for non-smokers with COPD | 1 | 0·98 | 0·90 | 0·96 | 0·60 | 0·76 | 0·838 | 80·8 |

| 8 | Comparison of the clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of exercise and education-based rehabilitation to improve health status with standard care in patients with pre-existing airways disease | 2 | 0·90 | 0·81 | 0·89 | 0·74 | 0·81 | 0·828 | 82·1 |

| 9 | Examination of the benefits of progressive or bespoke exercise rehabilitation delivered live or virtually for patients with airways disease and persistent symptoms or physical limitations after hospital discharge | 2 | 0·92 | 0·87 | 0·86 | 0·74 | 0·74 | 0·826 | 81·3 |

| 10 | Assessment of whether outcomes of patients admitted to hospital with acute COVID-19 and pre-existing airways disease treated with pre-COVID-19 long-term anticoagulants are better than for those not treated with long-term anticoagulants (eg, using in-patient length of stay, discharge rates, and long COVID-19 markers at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after hospital discharge) | 3 | 0·90 | 0·88 | 0·90 | 0·63 | 0·81 | 0·825 | 77·5 |

| 11 | Investigation of the effects of ethnicity on recovery of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and pre-existing asthma or COPD | 1 | 0·95 | 0·90 | 0·95 | 0·56 | 0·75 | 0·819 | 77·1 |

| 12 | Examination of whether use of inhaled corticosteroids in the preceding 12 months by patients with pre-existing airways disease is associated with greater in-patient COVID-19 disease burden (eg, on the SOFA score, length of hospital stay, or ventilation status) or increased post-COVID-19 rates of fatigue or sarcopenia | 1 | 0·94 | 0·88 | 0·88 | 0·67 | 0·71 | 0·817 | 77·5 |

| 13 | Identification of the predictors of a new diagnosis of bronchiectasis after COVID-19 on CT scans at 6 months after hospital discharge (eg, disease severity, length of stay, clinical history of sputum production, or sputum microbiology at ≥3 months) | 3 | 0·93 | 0·84 | 0·91 | 0·60 | 0·76 | 0·808 | 72·9 |

| 14 | Assessment of the effects of nutritional status (nutritional depletion or obesity) on recovery from COVID-19 in patients with airways disease and whether this can be modified by nutritional interventions | 1 | 0·87 | 0·79 | 0·80 | 0·78 | 0·78 | 0·804 | 77·9 |

| 15 | Estimation of the incidence of pulmonary embolism up to 1 year after acute COVID-19 | 1 | 0·95 | 0·95 | 0·98 | 0·47 | 0·67 | 0·802 | 78·8 |

| 16 | Comparison of rates of return to work at 6 months and 12 months between patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 with and without pre-existing airways disease | 4 | 0·96 | 0·93 | 0·95 | 0·51 | 0·66 | 0·802 | 78·3 |

| 17 | Examination of whether changes on chest x-ray and CT scans in patients with COVID-19 correlate with subsequent long-term symptoms and outcomes | 3 | 0·96 | 0·95 | 0·82 | 0·57 | 0·68 | 0·796 | 76·3 |

| 18 | Examination of whether patients with asthma and COPD who have had severe COVID-19 pneumonia develop additional long-term restrictive lung function impairment after recovery | 3 | 0·94 | 0·88 | 0·82 | 0·56 | 0·76 | 0·793 | 77·9 |

| 19 | Identification of the characteristics of patients with pre-existing airways disease that predict the need for non-invasive ventilation | 1 | 0·91 | 0·89 | 0·93 | 0·48 | 0·74 | 0·791 | 77·1 |

| 20 | Investigation of the effects of type and duration of anticoagulation treatment given after venous thromboembolism or as prophylaxis in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and pre-existing airways disease | 2 | 0·92 | 0·82 | 0·82 | 0·59 | 0·75 | 0·780 | 72·5 |

See main text for definition of subthemes. Scores for the predefined priority-setting criteria are also presented. AEA=average expert agreement. COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. ISARIC=International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infections Consortium.34 RPS=research priority score. SOFA=Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

A risk stratification score used to predict in-hospital mortality for patients with COVID-19.

The majority of the 20 research ideas with the lowest RPS values were from subthemes 2 and 5 (seven from each subtheme). They focused on understanding the role of interventions for COVID-19 on outcomes and development of innovative approaches to health care and policy-making initiatives for patients with chronic airways disease. The three lowest-ranked research topics related to the evaluation of the role of the private sector in pandemic management (RPS 0·339, AEA 0·638), alternative medicine in patients with COVID-19 with pre-existing airways disease (RPS 0·362, AEA 0·608), and the risk of developing lung cancer from acute or long COVID (RPS 0·446, AEA 0·588). Other low-ranking research ideas included determining priority for vaccination among COVID-19 survivors, exploring opportunities for artificial intelligence and advanced technologies such as xenon MRI in the assessment and treatment of patients with COVID-19, investigating the risk of developing pulmonary aspergillosis in COVID-19 survivors, and studying the perceptions and practices of general practitioners during the COVID-19 pandemic (appendix 1 pp 5–15).

Scores for the priority-setting criteria

Across three of the priority-setting criteria (answerability, feasibility, and timeliness), the highest scoring research idea was investigation of the correlation between prognostic scores at hospital admission and morbidity at 3 months and 12 months after discharge in patients with and without pre-existing airways disease (table 2 ). The second highest-ranking research idea for both feasibility and timeliness was estimation of the incidence of pulmonary embolism up to 1 year after acute COVID-19. Many of the three highest scoring research ideas for the priority-setting criteria were also among the 20 highest scoring ideas according to their overall RPS (table 2). A notable exception was investigation of whether patients at risk of persisting disability after COVID-19 can be identified and targeted for rehabilitation or nutritional interventions. This idea was ranked highest for both burden and equity criteria, but was ranked 21st in the overall list. Similarly, investigation of the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of people with COPD was ranked third for the answerability criterion, but 25th in the overall list, and development of scores to predict long-term respiratory disease severity and risk of mortality in survivors of severe COVID-19 was ranked third for the equity criterion, but 28th in the overall list (table 2). The ten highest scoring research ideas for each of the five criteria are presented in appendix 1 (pp 16–25) and the full list of 98 research ideas with scoring data for the five criteria are presented in appendix 2 (sheets 1–5).

Table 2.

Three highest-ranked research ideas for each of the predefined priority-setting criteria

| Research idea | RPS | AEA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Answerability | |||

| 1 | Investigation of the correlation between prognostic scores using the ISARIC 4C Mortality Score* at hospital admission and morbidity at 3 months and 12 months after hospital discharge in patients with and without pre-existing airways disease | 0·864 | 83·8 |

| 7 | Assessment of whether recovery from severe COVID-19 pneumonia is worse for current smokers with COPD than for non-smokers with COPD | 0·838 | 80·8 |

| 25 | Investigation of the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of people with COPD | 0·773 | 75·4 |

| Feasibility | |||

| 1 | Investigation of the correlation between prognostic scores using the ISARIC 4C Mortality Score* at hospital admission and morbidity at 3 months and 12 months after hospital discharge in patients with and without pre-existing airways disease | 0·864 | 83·8 |

| 15 | Estimation of the incidence of pulmonary embolism up to 1 year after acute COVID-19 | 0·802 | 78·8 |

| 17 | Examination of whether changes on chest x-ray and CT scans in patients with COVID-19 correlate with subsequent long-term symptoms and outcomes | 0·796 | 76·3 |

| Timeliness | |||

| 1 | Investigation of the correlation between prognostic scores using the ISARIC 4C Mortality Score* at hospital admission and morbidity at 3 months and 12 months after hospital discharge in patients with and without pre-existing airways disease | 0·864 | 83·8 |

| 15 | Estimation of the incidence of pulmonary embolism up to 1 year after acute COVID-19 | 0·802 | 78·8 |

| 2 | Assessment of whether 3-month and 6-month post-COVID-19 fatigue, sarcopenia, anxiety, and depression scores are worse in patients with pre-existing airways disease than in those without pre-existing airways disease, and whether any difference is significant when adjusted for severity of in-patient disease | 0·852 | 84·6 |

| Burden | |||

| 21 | Investigation of whether patients at risk of persisting disability after COVID-19 can be identified (eg, with disease indicators at the acute event, frailty scores, or nutritional scores) and targeted for rehabilitation, nutritional interventions, or both | 0·778 | 75·4 |

| 14 | Assessment of the effects of nutritional status (nutritional depletion or obesity) on recovery from COVID-19 in patients with airways disease and whether this can be modified by nutritional interventions | 0·804 | 77·9 |

| 5 | Development and validation of tools for remote monitoring of symptoms, and for self-monitoring of symptoms, especially in patients with pre-existing airways disease | 0·841 | 82·1 |

| Equity | |||

| 21 | Investigation of whether patients at risk of persisting disability after COVID-19 can be identified (eg, with disease indicators at the acute event, frailty scores, or nutritional scores) and targeted for rehabilitation, nutritional interventions, or both | 0·778 | 75·4 |

| 4 | Identification of the predictors of hospital readmission after COVID-19 in patients with pre-existing airways disease compared with those without pre-existing airways disease | 0·847 | 83·3 |

| 28 | Development of scores to predict long-term respiratory disease severity and risk of mortality in survivors of acute COVID-19 | 0·764 | 73·8 |

Research ideas are numbered by their overall RPS rank.26 AEA=average expert agreement. COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. ISARIC=International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infections Consortium.34 RPS=research priority score.

A risk stratification score used to predict in-hospital mortality for patients with COVID-19.

Patients' weighting

The patients' contributions offered insights into the overall ranking of the research ideas, providing additional perspectives for clinicians, researchers, and policy makers. 61 patients were recruited through the online survey. We do not have extensive data on the demographics of the patient survey respondents, but nearly half reported a pre-COVID-19 airways disease. Of the 61 patients who responded to the question on weighting of the criteria, 32·8% considered burden the most important criterion for setting research priorities for COVID-19 in airways disease, answerability and equity were each selected by 21·3% of patients, 18·0% chose feasibility, and 6·6% opted for timeliness (appendix 1 p 32).

Applying those weights to generate weighted RPS values led to four research ideas moving up into the weighted list of the 20 highest scoring topics. Of note were the ideas concerning investigation of the long-term effects of COVID-19 on the mental health of people with COPD and development of scores to predict long-term respiratory disease severity and risk of mortality in survivors of severe COVID-19—both already identified among the three highest research priorities according to answerability and equity criteria. The two other research ideas that moved into the weighted list of the 20 highest-ranking topics focused on assessment of the effectiveness of counselling and psychological services in addressing long-term psychological and cognitive effects of COVID-19 in patients with pre-existing airways disease and investigation of whether patients with pre-existing asthma develop an accelerated loss of lung function after severe COVID-19. In summary, the 20 highest scoring overall research priorities according to the weighted and individual RPS values were largely overlapping, although their rankings differed slightly (appendix 1 pp 26–28; the 20 lowest scoring overall ideas according to weighted RPS values are presented in appendix 1 pp 29–31).

Discussion

As the COVID-19 pandemic progresses into a second year, there is an increasing need to understand the burden of emerging or worsening pre-existing comorbidities. Here, we report the findings of a CHNRI research priority-setting exercise aimed at addressing this burden in relation to airways disease in people who have survived an acute illness due to COVID-19. Although the focus was on airways disease, many of the priorities identified would be broadly applicable to the study of long COVID and its management in patients not admitted to hospital or those with other comorbidities. The considerable diversity in topics covered by the highest-ranking research ideas—from identification of associated risk factors and assessment of incidence of events to investigation of the effects of interventions both in the acute setting and after hospital discharge—reflects the wide-ranging concerns about the burden of the long-term sequelae of COVID-19.

Key findings

The four highest-ranked research priorities focused on comparisons of the health outcomes of COVID-19 survivors with and without pre-existing airways disease. These priorities included exploration of correlations between prognostic scores (using the ISARIC 4C Mortality Score34) at hospital admission and post-discharge morbidity at 3 months and 12 months, and investigation of the potential risk of developing comorbidities or complications in COVID-19 survivors. Comorbidities and complications include fatigue, sarcopenia, anxiety, depression, cardiovascular complications, and hospital readmission. Investigation of the incidence and risk factors (eg, smoking and ethnicity) associated with developing new symptomatic airways disease or structural airways abnormalities on radiological imaging also featured in the 20 highest-ranked ideas. Additionally, investigation of correlations between imaging findings identified during acute COVID-19 illness and subsequent long-term symptoms and outcomes was ranked highly.

The importance of the increased incidence of venous thromboembolic disease in patients with COVID-19 was reflected in three of the 20 highest scoring ideas, including investigation of the incidence of pulmonary embolism and the role of anticoagulants—both newly administered and previously prescribed—on outcomes. Other ideas of interest among the experts included the role of interventions such as exercise-based rehabilitation programmes, nutritional interventions, and the use of acute non-invasive ventilation in patients with pre-existing airways disease. Research ideas from the subcategories addressing long-term effects of COVID-19 on quality of life, mental health, and social characteristics (subtheme 4), and development of innovative approaches to health care and policy-making initiatives (subtheme 5) for patients with chronic airways disease were less common among the 20 highest priorities, featuring one idea each.

Topics regarded as less important by the experts in this exercise were those that involved basic science research, the role of advanced technologies such as xenon MRI and artificial intelligence, and suggestions to develop or amend international guidelines. Other ideas with low scores included understanding perceptions of the private sector and primary care providers during the pandemic, and the prevalence of less frequently observed conditions such as invasive aspergillosis after severe pneumonia. These lower scores might have reflected concerns over deliverability in a pandemic situation (eg, for MRI-based studies) or the perception of low burden of disease (eg, for aspergillosis complicating COVID-19).

Strengths and limitations

The use of the standardised CHNRI method enabled a systematic, transparent, and democratic approach to identification of research priorities for long COVID in the setting of airways disease. Despite the pressures associated with the pandemic on clinicians and researchers, we achieved a return rate of more than 40%, which is similar to that for previous CHNRI exercises.24, 25 Furthermore, previous experience and statistical simulations have shown considerable convergence of collective expert opinion when the number of scoring experts is 40 or more, ensuring stability and replicability of the final rankings according to CHNRI methods;26, 28 consistent with this, we found a high degree of agreement among experts on the most highly-ranked research ideas according to the AEA values.

As a result of the good response rate, we were able to include opinions from a range of experts with both clinical and academic expertise, including some from low-income and middle-income countries. Although individuals from 36 nations were invited, we had no responses from experts in South America, and few participants from Africa and Asia, and the identified research priorities might therefore not be directly relevant to these regions. Similarly, although general practitioners with respiratory expertise and International Primary Care Respiratory Group members were invited, only a few experts from primary care took part in the study. The lower RPS values and relative lack of research priorities specific to primary care are likely to reflect the targeted population of COVID-19 survivors who had been admitted to hospital, but the involvement of relatively few primary care experts might have also been a contributing factor. As the burden of COVID-19 shifts from acute to chronic care, greater input from primary care experts in priority setting will be essential. Additional expertise relevant to the symptoms seen in long COVID—including input from neurological, psychological, renal, and cardiac fields—should be sought to capture diversity in research questions to feed into future priority-setting exercises.

The incorporation of patients' priorities was a novel aspect of our method that offers additional benefits for setting the directions for future research by ensuring that researchers, policy makers, and stakeholders are engaging in research that meets the needs of affected individuals. Our rapid, online patient survey allowed us to achieve a good number of respondents, although it is likely that views of certain patient groups were missed.

A limitation of this exercise was the large number of ideas that were unclear or that could not be addressed within the context of PHOSP-COVID research, which were removed during the internal review process (appendix 1 pp 2–4). Although we endeavoured to carefully rephrase research ideas to reflect the new knowledge they proposed to generate, some might have been poorly reworded, which might have contributed to some ideas being considered as lower priority. Interestingly, few of the proposed research priorities focused on non-respiratory comorbidities, which probably reflects the focus of this initiative on airways disease. Despite the respiratory focus, the absence of high-ranking research ideas relating to cystic fibrosis or sleep-related disorders is important to acknowledge.

Interpretation in the context of published studies

Clinicians and policy makers already recognise the need to follow up patients who have had acute COVID-19. However, understanding which subgroups of patients most need follow-up will be increased by addressing the research priorities outlined here. The development of the ISARIC 4C Mortality Score has helped to identify those at high risk of adverse outcomes during hospital admission.34 The ISARIC 4C Mortality Score is readily available and has been increasingly adopted in clinical practice.34 If subsequent studies show that this acute severity score also helps to identify those with greatest risk of more severe long COVID, it will facilitate service provision and treatment algorithms. Conversely, if correlations with acute illness scores are low, as suggested by some early data,2 then long COVID clinics might need a much larger service provision to provide follow-up to people with long COVID who were not admitted to hospital. This is highly relevant because the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly affected outpatient follow-up for long-term conditions across most medical specialties. Respiratory and infectious diseases are likely to be further disadvantaged owing to the key roles of these specialties in providing acute COVID-19 services.

Patients with airways disease have a recognised complex of comorbidities and (pre-COVID-19) clinical patterns that are relevant to COVID-19 and its multisystem disease manifestations. For example, acute COPD exacerbations are associated with a high hospital readmission rate—up to 40% at 3 months—and a long-term increased risk of vascular events, such as myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism.35 Similarly, acute COVID-19, with extrapulmonary disease, widely reported thrombotic events, and other multisystem effects,2, 34 can lead to complications after hospital discharge. Understanding the frequency and severity of complications in post-acute COVID-19 and identifying patient subgroups at highest risk of such complications should enable investigation of different intervention strategies, such as anticoagulant treatment after discharge, which might minimise early and late thromboembolism.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed, it has become clear that—unlike many other respiratory viruses—SARS-CoV-2 does not cause typical exacerbations of airways disease.36 Observational data have suggested that patients with COPD and selected subgroups with asthma have poorer outcomes than do patients without these pre-existing conditions.3, 5, 8, 9 Research into the role of inhaled steroid use in patients with pre-existing airways disease on COVID-19 disease burden was ranked 12th in our exercise according to its overall RPS. Some studies have suggested that inhaled steroid treatment might be protective against severe COVID-19.37 However, the available observational studies on inhaled steroids are potentially confounded by the effects of behavioural factors such as better adherence to treatments, shielding programmes, and a reduction of exposure to factors related to exacerbation events (eg, other infections and air pollution).

Thus, the effect of COVID-19 on patients with pre-existing airways disease, or with de-novo airways disease, needs to be studied prospectively in large cohorts of patients. These studies will need to have an appropriately matched control group with linked retrospective health-care data to ensure robust assessment of pre-COVID-19 health status. This priority-setting exercise provides a framework to address key research topics in this important patient group.

Implications for policy, practice, and research

This exercise showed a high level of concordance between experts and patients in the 20 highest scoring research topics when weighting of the criteria according to patients' input was included. The weighting led to some differences in the five highest priorities, but in general, the experts' ranks reflected patients' expectations. As a result, we expect that there will be positive engagement in terms of research participation to address the priority areas identified.

Many of the highly-ranked research topics could be addressed within a short time-frame, particularly with national and international coordination. Investigating the potential risk factors identified in the research priorities (eg, socioeconomic status, comorbidities, ethnicity, nutritional status, and medication use) could help to identify patients who are at highest risk of long COVID, which in turn will inform service development during a time of resource constraints and large backlogs in clinical follow-up of patients with long-term conditions. Understanding of the predictors and causes of hospital readmissions after COVID-19 might allow targeted interventions to minimise readmission and reduce the strain on hospital capacity. Care bundles (standardised assessment tools used by the COPD hospital team for patients admitted with acute COPD exacerbations both during the hospital stay and after discharge) to minimise COPD readmissions38 have been widely adopted and could provide the basis to inform post-acute COVID-19 care.

Development of multidisciplinary clinics for long COVID is already encouraged by policy makers and patient advocacy groups.39 These clinics can form the basis for multisite international studies and assessment of interventions to prevent additional morbidity (eg, anticoagulation studies) or enhance return to baseline (eg, rehabilitation studies to tackle sarcopenia).39 However, provision of and access to such multidisciplinary clinics could be challenging in some low-income and middle-income countries where numbers of health-care professionals per capita and resource availability are already lower than in high-income countries and are further stretched by the pandemic. Other challenges could include difficulties in defining caseload where access to COVID-19 testing is limited or there is incomplete or non-systematic assessment of patients—eg, with echocardiography, CT scanning, or lung diffusion capacity testing to identify people who are breathless and have developed myocardial dysfunction or interstitial lung disease, compared with those who are breathless with no radiological changes.

Conclusions

In summary, we have undertaken a robust expert consensus process to identify research priorities for long COVID in the context of airways disease, taking into account the views of a large group of international experts as well as those of patients who have had COVID-19 in association with pre-existing airways disease or who have developed airways disease after COVID-19. The rankings of the research priorities are likely to have been influenced by the current stage of the pandemic and the status of vaccine development and roll-out, as well as the knowledge base and backgrounds of the experts and patients. Involving a different group of participants (eg, with expertise in neurology, psychiatry, cardiovascular disease, or digital health) should be considered in future priority-setting exercises as understanding of the burden and symptom complex of long COVID increases. With the COVID-19 pandemic set to continue for the foreseeable future, we recommend that such prioritisation exercises be repeated when the initial priority areas have been addressed and as the knowledge base grows.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched PubMed for articles published from database inception to Jan 14, 2021, with no language restrictions, using the following combination of search terms: “health priorities OR priority setting OR resource allocation” AND “research” AND “COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus disease 2019 OR 2019-nCoV” AND “survivor* OR recover* OR persistent OR follow up OR discharge* OR long term OR sequelae”. The final list of references was selected for this Position Paper with the aim of providing an overview of the best available evidence.

Data sharing

All data for this study were linked, stored, and analysed within a secure online platform. All data have been de-identified where necessary and are available in appendix 2.

Declaration of interests

CEB reports grants from the Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 study during the conduct of the study. JRH reports personal fees and non-financial support from pharmaceutical companies (AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline) that make medicines to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, outside the submitted work. JDC reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Insmed, Novartis, Chiesi, and Zambon, outside the submitted work. PEP reports personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, and a grant and non-financial support from GlaxoSmithKline, outside the submitted work. AS reports grants from the Health Data Research UK BREATHE Hub, the Medical Research Council, and the National Institute for Health Research, during the conduct of the study. ADS has received medical education grant support for BRONCH-UK, a UK bronchiectasis network, from GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead, Chiesi, and Forest labs, and his institution receives fees for his work as coordinating investigator on a phase 3 trial in bronchiectasis sponsored by Bayer. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This study and the Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 study (PHOSP-COVID) consortium are supported by a grant to the University of Leicester from the Medical Research Council (MRC)–UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) rapid response panel to tackle COVID-19. The NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre is a partnership between the University Hospitals of Leicester National Health Service (NHS) Trust, the University of Leicester, and Loughborough University. The study was also supported by the UK Health Data Research BREATHE Hub. PHOSP-COVID is registered with the ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN10980107). The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit for publication. We acknowledge the contributions of the following experts who submitted research ideas: David Denning, Rachael Evans, Paula Kauppi, Paul Mcnamara, Shoaib Faruqi, Nikos Papadopoulos, Michael Wechsler, George Slavich, Sian Williams, and Neil Fitch. We also acknowledge the support of the following groups to the initiative: the Severe Asthma Registry Network, the UK Bronchiectasis Network and Biobank, the Asthma UK and British Lung Foundation Partnership, and the International Primary Care Respiratory Group. Martha McIlvenny contributed to the administration of the project. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, MRC–UKRI, NIHR, or DHSC.

Contributors

The International COVID-19 Airways Diseases Group consists of the Post-hospitalisation COVID-19 study (PHOSP-COVID) Airways Diseases Working Group (which is co-led by LGH and ADS and includes all authors of this paper) and the international collaborators. AS, IR, and DA conceptualised the research priority exercise. LGH, ADS, AS, IR, OE, LD, KP, and DA formed the Expert Management Group, a subgroup of the PHOSP-COVID Airways Diseases Working Group. The Expert Management Group defined the aims of the exercise and context, identified and contacted international experts as collaborators, and collected and analysed the results. KP and SW designed and organised the patients' survey. DA, LD, and OE wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. The PHOSP-COVID Airways Diseases Working Group members JKQ, SW, CEB, SS, JRH, JDC, PEP, PN, and TMD oversaw the exercise, contributed to the proposed research ideas, completed the scoresheets, and reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript. The international collaborators proposed research ideas, completed the scoresheets, and reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript. All authors were able to access the study data. DA, KP, OE, LD, IR, AS, ADS, and LGH accessed and verified all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the article for publication.

International collaborators

Australia Renae Mcnamara (University of Sydney, Sydney), Andrew Tai (Women's and Children's Hospital, Adelaide). Canada Anthony D'Urzo (University of Toronto, Toronto). Denmark Peter Schwarz, Charlotte Suppli Ulrik (Copenhagen University Hospital-Hvidovre, Copenhagen). France Marcel Bonay (University of Versailles, INSERM, Ambroise Paré Hospital, Boulogne), Arnaud Bourdin (University of Montpellier, CNRS, INSERM, CHU Montpellier, Montpellier). Hong Kong Fanny Wai San Ko (The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong). India Dhiraj Agarwal (KEM Hospital Research Centre, Pune), Jagadeesh Bayry (Indian Institute of Technology Palakkad, Palakkad). Iran Mohammad Abdollahi (Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran). Ireland Catherine M Greene (Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin). Italy Gaetano Caramori (University of Messina, Messina). Malaysia Ee Ming Khoo (University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur). Netherlands Louis J Bont (University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht), Gerard H Koppelman (University of Groningen, University Medical Centre Groningen, Beatrix Children's Hospital, Groningen). New Zealand Amy Hai Yan Chan (University of Auckland, Auckland). Saudi Arabia Riyad Al-Lehebi (King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh). South Africa Pisirai Ndarukwa (University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban). South Korea Chin Kook Rhee (The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul). Spain Cristóbal Esteban (Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo Hospital, Galdakao, Osakidetza, Bizkaia), Jose Luis Lopez-Campos (Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Universidad de Sevilla), Miguel A Martinez-Garcia (Hospital Universitari i Politècnic la Fe, Valencia), Marc Miravitlles (Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona). Sweden Magnus Ekström (Lund University, Lund), Karin Lisspers (Uppsala University, Uppsala). UK Peter J Barnes, Michael Loebinger (Imperial College London, London), Thomas Brown (Portsmouth Hospitals University NHS Trust, Portsmouth), David H Dockrell, Michelle C Williams (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh), Simon Doe (Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle), Jamie Duckers (Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, Cardiff), Atul Gupta, Matthew Maddocks (King's College Hospital, London), Brian J Lipworth (University of Dundee, Dundee), Alison Pooler (Keele University, Keele), Dominick Shaw (University of Nottingham, Nottingham), Michael Steiner (University of Leicester, Leicester), Paul Walker (University of Liverpool, Liverpool). USA Jennifer L Ingram (Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC), David Mannino (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY).

Contributor Information

International COVID-19 Airways Diseases Group:

Davies Adeloye, Omer Elneima, Luke Daines, Krisnah Poinasamy, Jennifer K Quint, Samantha Walker, Chris E Brightling, Salman Siddiqui, John R Hurst, James D Chalmers, Paul E Pfeffer, Petr Novotny, Thomas M Drake, Mohammad Abdollahi, Dhiraj Agarwal, Riyad Al-Lehebi, Peter J Barnes, Jagadeesh Bayry, Marcel Bonay, Louis J Bont, Arnaud Bourdin, Thomas Brown, Gaetano Caramori, Amy Hai Yan Chan, David H Dockrell, Simon Doe, Jamie Duckers, Anthony D'Urzo, Magnus Ekström, Cristóbal Esteban, Catherine M Greene, Atul Gupta, Jennifer L Ingram, Ee Ming Khoo, Fanny Wai San Ko, Gerard H Koppelman, Brian J Lipworth, Karin Lisspers, Michael Loebinger, Jose Luis Lopez-Campos, Matthew Maddocks, David Mannino, Miguel A Martinez-Garcia, Renae Mcnamara, Marc Miravitlles, Pisirai Ndarukwa, Alison Pooler, Chin Kook Rhee, Peter Schwarz, Dominick Shaw, Michael Steiner, Andrew Tai, Charlotte Suppli Ulrik, Paul Walker, Michelle C Williams, Liam G Heaney, Igor Rudan, Aziz Sheikh, and Anthony De Soyza

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO Coronavirus disease dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brodin P. Immune determinants of COVID-19 disease presentation and severity. Nat Med. 2021;27:28–33. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultze A, Walker AJ, MacKenna B, et al. Risk of COVID-19-related death among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma prescribed inhaled corticosteroids: an observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1106–1120. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30415-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adeloye D, Chua S, Lee C, et al. Global and regional estimates of COPD prevalence: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2015;5 doi: 10.7189/jogh.05-020415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Asthma Network . Global Asthma Network; Auckland, New Zealand: 2018. The Global Asthma Report 2018.http://globalasthmareport.org/Global%20Asthma%20Report%202018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung JM, Niikura M, Yang CWT, Sin DD. COVID-19 and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2020;56 doi: 10.1183/13993003.02108-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skevaki C, Karsonova A, Karaulov A, Xie M, Renz H. Asthma-associated risk for COVID-19 development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:1295–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UK Government COVID-19: long-term health effects. 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-long-term-health-effects/covid-19-long-term-health-effects

- 12.World Health Organization What we know about Long-term effects of COVID-19. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/risk-comms-updates/update-36-long-term-symptoms.pdf?sfvrsn=5d3789a6_2 (in French).

- 13.Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a multistate health care systems network—United States, March–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:993–998. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office for National Statistics The prevalence of long COVID symptoms and COVID-19 complications. 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/news/statementsandletters/theprevalenceoflongcovidsymptomsandcovid19complications

- 15.Mandal S, Barnett J, Brill SE, et al. ‘Long-COVID’: a cross-sectional study of persisting symptoms, biomarker and imaging abnormalities following hospitalisation for COVID-19. Thorax. 2021;76:396–398. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hester KL, Macfarlane JG, Tedd H, et al. Fatigue in bronchiectasis. QJM. 2012;105:235–240. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Wu F, Yi H, et al. Gender differences in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease symptom clusters. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:1101–1107. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S302877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heslop K, Newton J, Baker C, Burns G, Carrick-Sen D, De Soyza A. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) interventions for anxiety in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) undertaken by respiratory nurses: the COPD CBT CARE study: (ISRCTN55206395) BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodd JW, Getov SV, Jones PW. Cognitive function in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:913–922. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00125109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Børvik T, Brækkan SK, Enga K, et al. COPD and risk of venous thromboembolism and mortality in a general population. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:473–481. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00402-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raj SR, Arnold AC, Barboi A, et al. Long-COVID postural tachycardia syndrome: an American Autonomic Society statement. Clin Auton Res. 2021;31:365–368. doi: 10.1007/s10286-021-00798-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roig M, Eng JJ, Road JD, Reid WD. Falls in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a call for further research. Respir Med. 2009;103:1257–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gemelli Against C-P-ACSG Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:1613–1620. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01616-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudan I, El Arifeen S, Bhutta ZA, et al. Setting research priorities to reduce global mortality from childhood pneumonia by 2015. PLoS Med. 2011;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontaine O, Kosek M, Bhatnagar S, et al. Setting research priorities to reduce global mortality from childhood diarrhoea by 2015. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudan I, Yoshida S, Chan KY, et al. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: VII. A review of the first 50 applications of the CHNRI method. J Glob Health. 2017;7 doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.011004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudan I, Yoshida S, Wazny K, Chan KY, Cousens S. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: V. Quantitative properties of human collective knowledge. J Glob Health. 2016;6 doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.010502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida S, Rudan I, Cousens S. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: VI. Quantitative properties of human collective opinion. J Glob Health. 2016;6 doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.010503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudan I, Yoshida S, Chan KY, et al. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: I. Involving funders. J Glob Health. 2016;6 doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.010301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshida S, Cousens S, Wazny K, Chan KY. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: II. Involving researchers. J Glob Health. 2016;6 doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.010302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida S, Wazny K, Cousens S, Chan KY. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: III. Involving stakeholders. J Glob Health. 2016;6 doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.010303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudan I. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: IV. Key conceptual advances. J Glob Health. 2016;6 doi: 10.7189/jogh-06-010501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudan I, Gibson JL, Ameratunga S, et al. Setting priorities in global child health research investments: guidelines for implementation of CHNRI method. Croat Med J. 2008;49:720–733. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.49.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knight SR, Ho A, Pius R, et al. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: development and validation of the 4C Mortality Score. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alqahtani JS, Njoku CM, Bereznicki B, et al. Risk factors for all-cause hospital readmission following exacerbation of COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29 doi: 10.1183/16000617.0166-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beurnier A, Jutant EM, Jevnikar M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of asthmatic patients with COVID-19 pneumonia who require hospitalisation. Eur Respir J. 2020;56 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01875-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Izquierdo JL, Almonacid C, González Y, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on patients with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2021;57 doi: 10.1183/13993003.03142-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zafar MH, Panos RJ, Ko J, et al. Reliable adherence to a COPD care bundle mitigates system-level failures and reduces COPD readmissions: a system redesign using improvement science. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26:908–918. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yelin D, Wirtheim E, Vetter P, et al. Long-term consequences of COVID-19: research needs. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30701-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data for this study were linked, stored, and analysed within a secure online platform. All data have been de-identified where necessary and are available in appendix 2.