Abstract

Importance:

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes (“CMS National Partnership”) focuses on reducing antipsychotic prescribing to long-term care residents. Hospice enrollment is not an exclusionary condition for the antipsychotic quality measure reported by CMS. It is unclear how prescribing in hospice may have been impacted by the initiative.

Objective:

Estimate the association of the CMS National Partnership with trends in antipsychotic prescribing among long-term care residents in hospice.

Design:

Interrupted time-series analysis of a 100% Minimum Data Set sample with linked hospice claims from 2011–2017.

Setting:

Long-term care nursing facilities.

Participants:

Older adults ≥65 residing in long-term care (n=3,741,379) and limited to those enrolled in hospice (n=821,610).

Main Outcome:

Quarterly prevalence of antipsychotic and other psychotropic (antianxiety, hypnotic, antidepressant) use among long-term care residents; overall and among residents with dementia, stratified by hospice enrollment.

Results:

From 2011–2017, parallel declines in antipsychotic prescribing were observed among long-term care residents enrolled and not enrolled in hospice (hospice: decline from 26.8% to 18.7%; non-hospice: decline from 23.0% to 14.4%). Following the 2012 CMS National Partnership, quarterly rates of antipsychotic prescribing declined significantly for both residents enrolled and not enrolled in hospice care. Declines in antipsychotic prescribing were greater for residents with dementia, with similar rates among residents enrolled and not enrolled in hospice. Among residents with dementia enrolled in hospice, use of other psychotropic medication classes including antianxiety, antidepressant, and hypnotic use remained relatively stable over time.

Conclusions and Relevance:

Declines in antipsychotic prescribing during the CMS National Partnership occurred among long-term care residents in hospice, where use may be deemed clinically appropriate. Nursing homes are an important location for the provision of dementia end-of-life care and the drivers of potentially unintended reductions in antipsychotic use merits further investigation.

Keywords: Hospice, nursing home, antipsychotic medication

INTRODUCTION

The 2012 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes (“CMS National Partnership”) was established to improve the quality of care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) by reducing potentially inappropriate antipsychotic prescribing to long-term care residents.1,2 Starting in 2015, CMS began publicly reporting a quality measure of antipsychotic use for each nursing home facility through the Nursing Home Compare website and the Five Star Quality Rating System.3 Thus, nursing home homes are incentivized to reduce antipsychotic prescribing to long-term care residents so as to maintain or improve their reported quality rating.

Nursing homes are an important location for the provision of dementia end-of-life care, with over 50% of patients with ADRD dying in nursing homes.4,5 Antipsychotic and benzodiazepine medications are routinely used for end of life symptom management for patients enrolled in hospice and are common components of the hospice “comfort” kit.6 Such medications are often prescribed by hospice providers to provide comfort and sedation during the active dying period and are used to treat both behavioral (e.g., anxiety, agitation, terminal restlessness) and physical (e.g., nausea) symptoms during end-of-life care. Patients enrolled in hospice represent a unique clinical population and are typically excluded from more general prescribing recommendations regarding potentially inappropriate medication use among older adults, such as the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria.7 While residents receiving hospice care are excluded from the Nursing Home Compare quality measure of percent of long-stay residents prescribed antianxiety and hypnotic medications, there is no such hospice exclusion for the antipsychotic prescribing long-stay quality measure.8 Concerns have been raised that this failure to account for hospice status may interfere with the ability of nursing home hospice residents to receive antipsychotics medications when deemed clinically appropriate by a prescribing provider.9

According to CMS, antipsychotic prescribing to long-stay nursing home residents overall has decreased by 40% since the start of the CMS National Partnership.10,11 However, it is unknown if the CMS National Partnership recommendations have diffused more broadly to influence antipsychotic prescribing trends within nursing home hospice care—where use may be considered appropriate by hospice physicians—as these residents are not excluded from the CMS long-stay antipsychotic quality measure. Further, initiatives focused on reducing antipsychotic use among long-term care residents may lead to substitution of antipsychotics with other classes of medications not subject to the CMS National Partnership recommendations or tied to quality ratings such as antianxiety, hypnotic, or antidepressant medications. This analysis uses national Minimum Data Set (MDS) data to examine three clinically important effects: potentially unintended effects of the CMS National Partnership on antipsychotic treatment of patients enrolled in hospice; changes in long-term care antipsychotic prescribing among residents with ADRD in hospice; and changes in the use of specific medication classes over time among long-term care residents with ADRD enrolled in hospice.

METHODS

We examined the association between the initiation of the CMS National Partnership and Five Star Quality Ratings with antipsychotic prescribing among long-stay nursing home residents by hospice status and among residents with dementia. To assess whether other medications were potentially substituted for use of antipsychotics, we explored the association between use of other medication classes (e.g., antianxiety, antidepressant, hypnotic, and analgesics) following the CMS National Partnership in 2012 and introduction of the Five Star Quality Ratings in 2015. This study was approved by the Brown University institutional review board, which waived informed consent for these deidentified data.

Data Source and Study Cohort.

Data were drawn from a 100% sample of nursing home resident assessment data (Minimum Data Set; MDS) and hospice claims files from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2017. Using MDS data, we first constructed quarterly cohorts of long-stay residents of nursing facilities. A resident was included in a given quarterly cohort if they met criteria for long-stay (>100 days) for at least one day during the quarter, had a target MDS assessment completed during the quarter that coincided with their long-stay period, and were ≥65 years of age at the time of assessment. Further, we excluded those with an active diagnosis of schizophrenia, Tourette’s syndrome, and Huntington’s disease to match the exclusion criteria that CMS uses for its antipsychotic monitoring (e.g., for Nursing Home Compare and the CMS National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care) during a given quarter.8 Using the long-stay quarterly cohorts, residents with ADRD were identified based on active diagnosis codes in the MDS assessments. Finally, hospice enrollment status among long-stay residents in a given quarter was determined using linked Medicare hospice claims files.

Outcomes.

The outcomes of interest were antipsychotic and other central nervous system (CNS)-active medication use during a given quarter, the latter of which may represent potential substitution medications. Medication use was obtained from Section N of MDS version 3.0 target assessments which contains information on medications administered and received by the nursing home resident within the past 7 days, including antipsychotic, antianxiety, antidepressant, and hypnotic medications. Consistent with other studies utilizing MDS data, the pharmacologic treatment of pain was designated as receipt of either scheduled or as needed analgesic medication during a 5-day look back period.12

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

Age, gender, and race/ethnicity were obtained from the MDS target assessments. In addition to demographic data, a number of clinical measures from the MDS were obtained to describe resident clinical status. The Agitated and Reactive Behavior Scale (ARBS) was used to evaluate the level of physical and verbal agitation as well as resident resistance to care.13 For residents’ physical function, the 28-point Morris Activities of Daily Living Scale was used.14,15 Cognitive status was assessed using the Cognitive Function Scale (CFS).16 We also calculated the Changes in Health, End-Stage Disease and Symptoms and Signs (CHESS) score to indicate health instability and likelihood of future mortality.17

Statistical Analysis.

To examine the association of the CMS National Partnership and Five Star Quality Rating System with antipsychotic use among long-stay residents in hospice, we fit a 3-phase interrupted time series regression model. The 3 phases were: 1) before the 2012 CMS National Partnership (“pre-Partnership period”: 2011, quarter 1, through 2012, quarter 1); 2) after the CMS National Partnership (“post-Partnership period”: 2012, quarter 2, through 2014, quarter 4); and 3) after the addition of the antipsychotic use criterion to the Five Star Quality Rating System (“Five Star Quality Rating System”: 2015, quarter 1, through 2017, quarter 4) (Figure 1). The quarterly percentage using antipsychotics was the dependent variable and the model included a linear time-trend variable, indicators for post-Partnership and post-Five Star Quality Rating System, and terms for change in the linear time trend between the study periods (e.g., between the pre-Partnership and post-Partnership periods). Coefficients for the two indicators represent immediate changes to percent antipsychotic use associated with the CMS National Partnership and Five Star Quality Rating System, respectively, whereas coefficients for the post-Partnership and post-Five Star Quality Rating System time trends represent differences in the slope (i.e., expected quarterly change in percent) relative to the preceding period.

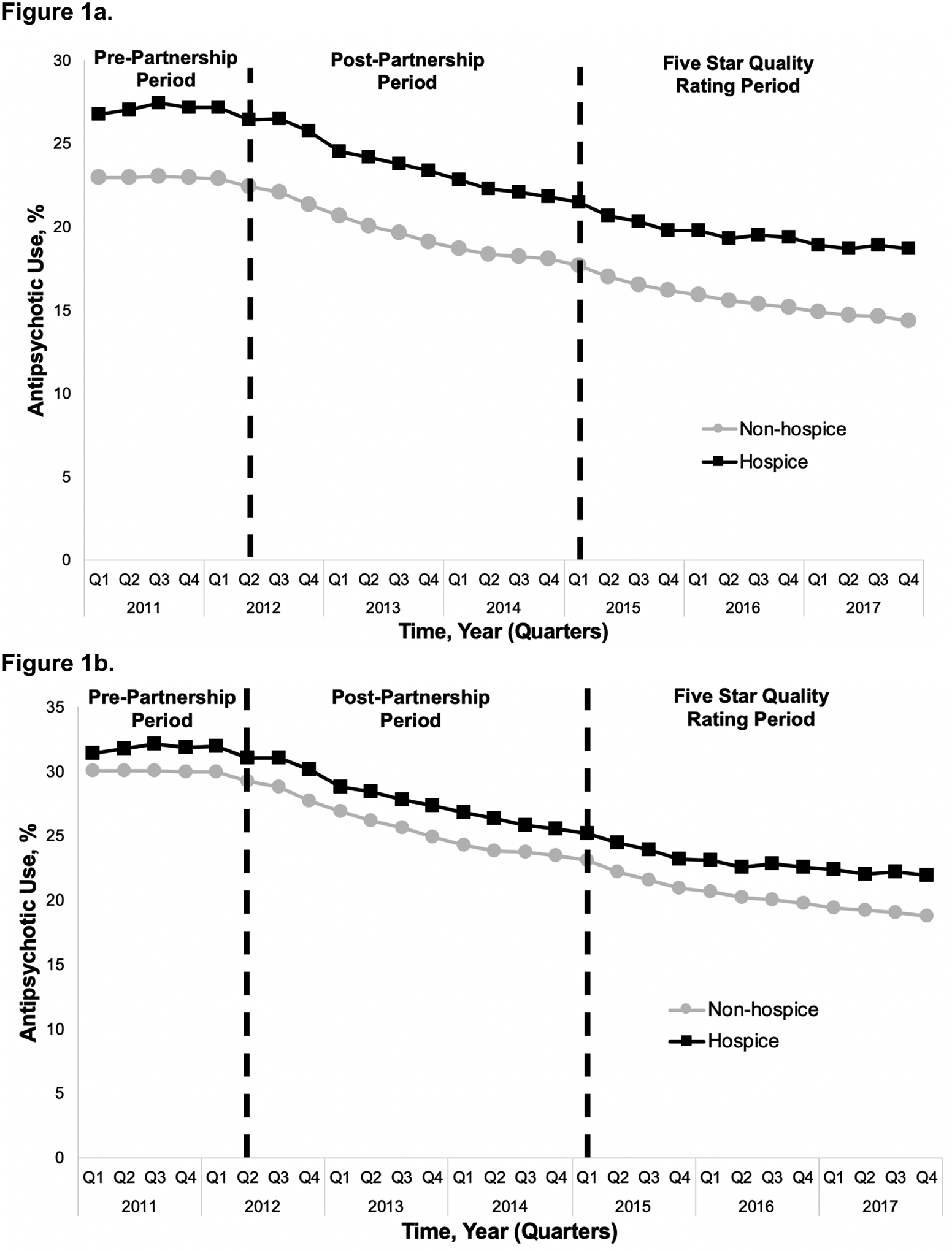

Figure 1a and 1b.

Percent of long-stay nursing home residents prescribed antipsychotics (1a) by hospice enrollment status and (1b) by hospice enrollment status among residents with dementia.

We examined autocorrelation using the Cumby-Huizinga test; based on results of the Cumby-Huizinga test, we refit the model with the appropriate lag and Newey-West standard errors. We repeated these steps to examine antipsychotic use among long-stay residents not in hospice and among long-stay residents with dementia. Finally, among long-stay residents with dementia enrolled in hospice, we repeated these steps substituting antianxiety, antidepressant, hypnotic, and pain treatment for antipsychotic use. All analyses were conducted using the itsa package in Stata 16.0.18 Alpha was set at 0.05 and all tests were two-sided.

RESULTS

Study Cohort Characteristics.

The cohort for the primary analysis included 3,741,379 long-stay (>100 days) nursing home residents between 2011–2017; 821,610 long-stay residents were enrolled in hospice for at least one quarter during the study period. Among 1,395,146 long-stay nursing home residents in 2011, the mean age was 83.7 years; the majority of residents overall were female (71.1%) and white (81.9%; Table 1). Further, 910,227 (65.2%) of residents had a diagnosis of ADRD.

Table 1.

Characteristics of long-stay nursing home residents in 2011, overall and by hospice enrollment status

| Characteristica | Overall N=1,395,146 |

Not in hospiceb N=1,240,930 |

Hospice N=154,216 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of assessments in 2011 | 2,638,948 | 2,326,566 | 312,382 |

| Age at nursing home entry, y (mean [SD]) | 83.65 (8.36) | 83.39 (8.39) | 85.73 (7.87) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 403,417 (28.9%) | 362,942 (29.3%) | 40,475 (26.3%) |

| Female | 991,729 (71.1%) | 877,988 (70.8%) | 113,741 (73.8%) |

| Race | |||

| White | 1,142,784 (81.9%) | 1,008,273 (81.3%) | 134,511 (87.2%) |

| Black | 160,112 (11.5%) | 147,552 (11.9%) | 12,560 (8.1%) |

| Hispanic | 63,002 (4.5%) | 57,861 (4.7%) | 5,141 (3.3%) |

| Other | 29,248 (2.1%) | 27,244 (2.2%) | 2,004 (1.3%) |

| Clinical conditions | |||

| Dementia | 910,227 (65.24%) | 795,346 (64.09%) | 114,881(74.49%) |

| MDS Clinical assessments | |||

| Average ADL, mean (SD) | 17.44 (6.70) | 17.02 (6.74) | 20.86 (5.31) |

| Average CHESS, mean (SD) | 0.91 (0.92) | 0.81 (0.85) | 1.67 (1.04) |

| Average CFS, mean (SD) | 2.45 (0.96) | 2.39 (0.96) | 2.90 (0.88) |

| Average ARBS scale score, mean (SD) | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.29 (0.45) |

SD, standard deviation; ADL, Activities of Daily Living; CHESS, Changes in Health, End-Stage Disease and Symptoms and Signs; CFS, Cognitive Function Scale; ARBS, Agitated and Reactive Behavior Scale; MDS, Minimum Data Set.

Characteristics taken from MDS assessments in 2011. When a long-stay resident had more than one assessment in 2011, the resident-level mean was computed.

Each of the 1,395,146 long-stay nursing home residents in 2011 were categorized according to whether they were enrolled in hospice while a long-stay resident during 2011 or not.

Antipsychotic Prescribing among Long-Stay Residents by Hospice Enrollment Status and Dementia Diagnosis

Figure 1a presents the percentage of long-stay nursing home residents prescribed an antipsychotic medication on a quarterly basis before (pre-Partnership period) and during (post-Partnership period) the CMS National Partnership as well as following the introduction of the Five Star Quality Rating System (Five Star Quality Rating period) by hospice enrollment status (Supplementary Table S1 presents the quarterly rates represented in Figure 1a and 1b). At the start of 2011, 26.8% of long-stay residents enrolled in hospice were prescribed an antipsychotic while 23.0% of long-stay residents not enrolled in hospice were prescribed an antipsychotic. Following the 2012 CMS National Partnership (post-Partnership period), parallel declines in the rate of antipsychotic prescribing were observed among long-stay residents enrolled in hospice (slope change = −0.60, p < 0.001) and those not enrolled in hospice (slope change = −0.46, p < 0.001; Table 2). By the end of the study period following the Five Star Quality Rating period (2017, quarter 4), antipsychotic use had fallen to 18.7% among those enrolled in hospice and 14.4% among those not enrolled in hospice, representing a 30.2% and 37.4% absolute percent change from the start of the study period, respectively. While the overall rate of antipsychotic use continued to decline during the Five Star Quality rating period, the quarterly rate of decline was slower relative to the post-Partnership period among both groups (hospice: slope change = 0.28, p < 0.001; non-hospice: slope change = 0.18, p < 0.01). This means that, while the slope during the Five Star Quality rating period remained negative, it was smaller in absolute value relative to the slope during the post-Partnership period.

Table 2.

Rate and trends in quarterly antipsychotic use among long-stay residents, by hospice enrollment status and dementia diagnosisa,b

| Residents Overall N=3,741,379 |

Residents with Dementia N=2,388,991 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-stay residents not in hospice N=3,610,536c |

Hospice enrollees N=821,610c |

Long-stay residents not in hospice N=2,277,341 |

Hospice enrollees N=579,599 |

||||||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | ||||

| Period 1 (2011–2012_Q1) | |||||||||||

| % Use at start of pre-Partnership Period | 22.99*** | 22.95, 23.03 | 26.94*** | 26.64, 27.24 | 30.12*** | 30.08, 30.17 | 31.63*** | 31.34, 31.92 | |||

| Slope during pre-Partnership Period | −0.004 | −0.02, 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.01, 0.21 | −0.04*** | −0.06, −0.02 | 0.11* | 0.004, 0.21 | |||

| Period 2 (2012_Q2–2014) | |||||||||||

| Level change | −0.75** | −1.21, −0.30 | −0.93** | −1.52, −0.35 | −0.98** | −1.56, −0.40 | −1.12** | −1.76, −0.47 | |||

| % Use at start of Period 2 | 22.22*** | 21.79, 22.64 | 26.49*** | 26.03, 26.95 | 28.95*** | 28.40, 29.51 | 31.06*** | 30.52, 31.59 | |||

| Slope change pre- and post-Partnership | −0.46*** | −0.53, −0.39 | −0.60*** | −0.73, −0.47 | −0.57*** | −0.67, −0.48 | −0.70*** | −0.83, −0.57 | |||

| Period 3 (2015_Q1–2017) | |||||||||||

| Level change | 0.08 | −0.37, 0.54 | −0.10 | −0.69, 0.48 | 0.14 | −0.46, 0.75 | −0.13 | −0.84, 0.57 | |||

| % Use at start of Period 3 | 17.21*** | 16.85, 17.58 | 20.86*** | 20.32, 21.41 | 22.37*** | 21.83, 22.92 | 24.45*** | 23.77, 25.13 | |||

| Slope change after Five Star Quality Rating | 0.18** | 0.07, 0.30 | 0.28*** | 0.16, 0.39 | 0.26** | 0.10, 0.41 | 0.33*** | 0.20, 0.46 | |||

CL, confidence interval.

<0.05;

<0.01;

<0.001.

Percent use reported here is predicted percent use from the interrupted time series model. Percent use after an interruption (e.g., start of Period 2) accounts for the interruption (i.e., level change included in estimate). Observed percent use can be found in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

The sample size reported here refers to the number of unique long-stay residents from 2011–2017 (e.g., there were 821,610 unique long-stay residents enrolled in hospice for at least one quarter from 2011 to 2017)

Because a long-stay resident can transition from not being enrolled in hospice to being enrolled in hospice, the number of long-stay residents not in hospice and in hospice do not add up to the total number of unique long-stay residents.

Among long-stay residents with a diagnosis of ADRD, Figure 1b presents the percentage of residents prescribed an antipsychotic by hospice enrollment status throughout the three study periods. At the start of 2011, the rates of antipsychotic use were higher among patients with ADRD than among the overall study sample, with 31.5% of residents with ADRD in hospice and 30.1% of residents with ADRD not enrolled in hospice prescribed antipsychotic medications. Among long-stay residents with ADRD not in hospice, the rate of antipsychotic use began to fall during the pre-Partnership period (i.e., even before the start of the CMS National Partnership) (slope = −0.04, p < 0.001; Table 2). Conversely, among residents with ADRD enrolled in hospice, the rate of antipsychotic use was increasing (slope = 0.11, p = 0.04) during the pre-Partnership period. Following the 2012 CMS National Partnership (post-Partnership period), parallel declines in the rate of antipsychotic prescribing were observed among long-stay residents with ADRD enrolled in hospice (slope change = −0.70, p < 0.001) and among those not enrolled in hospice (slope change = −0.57, p < 0.001; Table 2). As with long-stay residents overall, the quarterly rate of decline in antipsychotic use slowed significantly from the post-Partnership to Five Star Quality rating period among both groups (hospice: slope change = 0.33, p < 0.001; non-hospice: slope change = 0.26, p <0.01). At the end of the study period, antipsychotic prescribing had been reduced to 22.0% of residents with ADRD in hospice and 18.8% of residents with ADRD not in hospice, representing a 30.2% and 37.5% absolute percent change, respectively.

Antipsychotic and Other Psychotropic Medication Prescribing among Long-Stay Residents with Dementia Enrolled in Hospice

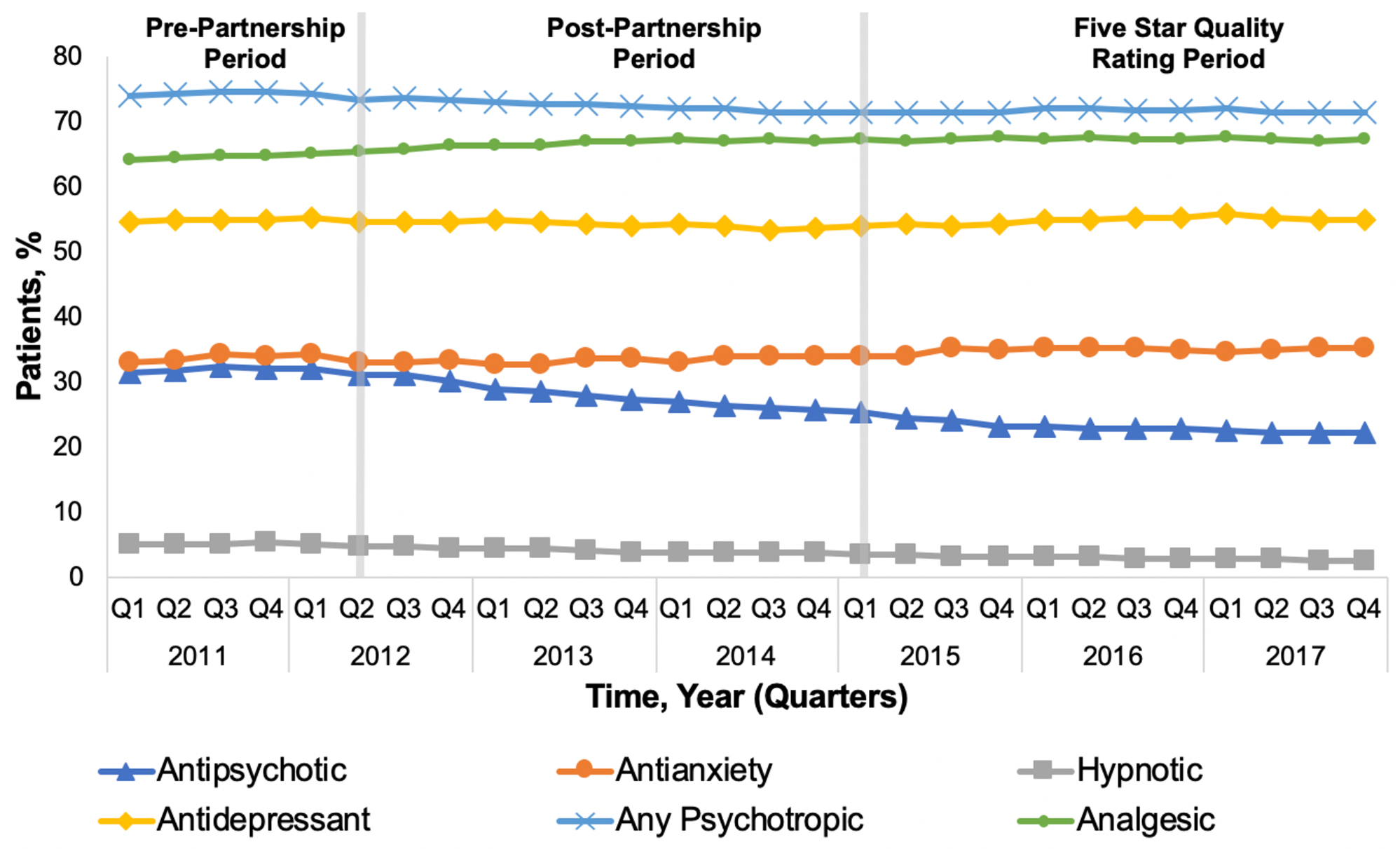

Among the subset of patients with ADRD enrolled in hospice, Figure 2 presents the percentage of patients prescribed antipsychotic or other CNS-active medication (Supplementary Table S2 presents the quarterly rates represented in Figure 2). Prior to the start of the CMS National Partnership (pre-Partnership period), utilization of all medication classes except hypnotics was increasing (Table 3). Following the CMS National Partnership and Five Star Quality Rating system, there was no clear pattern of substitution of other CNS-active medications following reductions in antipsychotic prescribing (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percent of long-stay nursing home residents with a diagnosis of dementia enrolled in hospice care with antipsychotic and comparison medication use

Table 3.

Rates and trends in quarterly antipsychotic and comparison medication prescribing among long-stay residents with a dementia diagnosis enrolled in hospice (N=579,599 hospice enrollees)a

| Antipsychotic | Antianxiety | Antidepressant | Hypnotic | Analgesic | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | |||||

| Period 1 (2011–2012_Q1) | ||||||||||||||

| % Use at beginning of pre-Partnership Period | 31.63*** | 31.34, 31.92 | 32.95*** | 32.66, 33.26 | 54.57*** | 54.46, 54.68 | 4.98*** | 4.91, 5.06 | 64.14*** | 64.03, 64.25 | ||||

| Slope during pre-Partnership Period | 0.11* | 0.004, 0.21 | 0.34**** | 0.22, 0.46 | 0.12*** | 0.07, 0.16 | 0.03 | −0.001, 0.07 | 0.24*** | 0.19, 0.28 | ||||

| Period 2 (2012_Q2–2014) | ||||||||||||||

| Level change | −1.12** | −1.76, −0.47 | −1.89*** | −2.48, −1.30 | −0.47** | −0.82, −0.13 | −0.36*** | −0.48, −0.25 | 0.42* | 0.10, 0.74 | ||||

| % Use at start of Period 2 | 31.06*** | 30.52, 31.59 | 32.75*** | 32.39, 33.11 | 54.69*** | 54.32, 55.07 | 4.78*** | 4.73, 4.83 | 65.75*** | 65.38, 66.11 | ||||

| Slope change pre- and post-Partnership | −0.70*** | −0.83, −0.57 | −0.23** | −0.35, −0.11 | −0.22*** | −0.31, −0.14 | −0.16*** | −0.20, −0.13 | −0.08 | −0.17, 0.01 | ||||

| Period 3 (2015_Q1–2017) | ||||||||||||||

| Level change | −0.13 | −0.84, 0.57 | 0.48 | −0.26, 1.22 | 0.47 | −0.04, 0.97 | 0.03 | −0.06, 0.12 | −0.17 | −0.57, 0.24 | ||||

| % Use at start of Period 3 | 24.45*** | 23.77, 25.13 | 34.36*** | 33.68, 35.05 | 54.01*** | 53.56, 54.45 | 3.36*** | 3.30, 3.43 | 67.30*** | 67.00, 67.59 | ||||

| Slope change after Five Star Quality Rating | 0.33*** | 0.20, 0.46 | −0.04 | −0.14, 0.07 | 0.22*** | 0.12, 0.33 | 0.04*** | 0.02, 0.05 | −0.17** | −0.27, −0.08 | ||||

CI, confidence interval.

<0.05;

<0.01;

<0.001.

Percent use reported here is predicted percent use from the interrupted time series model. Percent use after an interruption (e.g., start of Period 2) accounts for the interruption (i.e., level change included in estimate). Observed percent use can be found in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Analgesics were the most commonly prescribed medication class at all time points, and the only medication class for which use did not decline following the CMS National Partnership (Table 3). The overall use of analgesics increased marginally from 64.0% at the start of the study period (quarter 1, 2011) to 67.1% at the end of the study (quarter 4, 2017).

Antidepressant medications were the next most commonly prescribed medication class to long-stay residents with ADRD enrolled in hospice, with 54.5% of residents prescribed antidepressants at the start of the study period in 2011. Rates of antidepressant use remained largely steady throughout the study period. Antianxiety medications were the next most common medication class, prescribed to 32.8% of residents at the start of the study period. Rates of antianxiety medication use also remained largely stable throughout the study, with 35.0% of residents prescribed antianxiety medications at the end of 2017. Lastly, the rate of hypnotic medication prescribing remained low throughout the study period, with only 2.3% of long-stay residents with ADRD enrolled in hospice prescribed hypnotics by the end of the study.

DISCUSSION

In this analysis examining CNS-active medication prescribing before and during the CMS National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care, we found that antipsychotic treatment declined significantly in patients residing in long-term care following the CMS National Partnership. However, declines in antipsychotic prescribing were not just limited to patients with ADRD, the intended target of the CMS National Partnership. Parallel declines in antipsychotic prescribing were also observed among long-stay residents enrolled in hospice—a population for which use of these medications may be deemed clinically appropriate by hospice physicians—representing a 30% absolute percent change in use of antipsychotic medications among patients in hospice. Similar declines in antipsychotic prescribing were observed among patients with ADRD for both residents enrolled and not enrolled in hospice services. This did not appear to be offset by an increase in other CNS-active medication use for patients with dementia enrolled in hospice.

Reducing antipsychotic prescribing in dementia has become an intense focus of regulatory efforts following the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) black box warnings in 2005 and 2008, which highlighted increased mortality risk with both atypical and typical antipsychotic treatment of dementia-related behaviors19 and reports of elevated risk of stroke.20 The CMS National Partnership was introduced to improve dementia care which was initially defined as reducing antipsychotic prescribing among long-term care residents to decrease unnecessary overmedication and potential harms to persons with ADRD.11 Studies evaluating changes in prescribing following the CMS National Partnership have shown that reductions in antipsychotic prescribing have been widespread, with facility reductions as high as 45% reported.11,21 While some antipsychotic prescribing among persons with ADRD may be substituted by recommended first-line non-pharmacologic treatment interventions, reports from long-term care staff suggest considerable challenges in implementing such non-pharmacologic treatment strategies given staff turnover and limited resources to implement such interventions.22 We found that antipsychotic prescribing also declined significantly among long-stay residents enrolled in hospice care, which was not the intention of the CMS National Partnership. While the response to the CMS National Partnership may reduce unwarranted antipsychotic prescribing and subsequent medication related harms within hospice,23,24 the intended target of the initiative was not to reduce use among terminally ill residents, including those with malignancies, where medication may be recommended for symptom palliation (e.g., olanzapine treatment of nausea,25 sedation to address terminal agitation26) at the end of life.

There are currently few randomized controlled trials to inform the benefit of antipsychotic use among patients enrolled in hospice or with limited life effectancy.24,25,27,28 Of these available trials, relatively few demonstrate robust benefit with antipsychotic use for treatment of behavioral (e.g., agitated delirium)29 or physical (e.g., haloperidol for treatment of nausea)25 symptoms. Despite this lack of available evidence, antipsychotics are routinely prescribed for symptom management in hospice and palliative settings based on provider experience and anecdotal evidence that these medications are helpful.26

In the setting of these prescribing initiatives to drive down antipsychotic use, concerns have been raised from long-term care staff and hospice physicians that this has led to an “overcorrection” in which antipsychotics are being withheld from residents where use of these medications are deemed indicated by hospice physicians.9 National guidelines on safe prescribing for older adults, including the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria, recognizes patients in palliative and hospice settings as a unique clinical population and excludes patients in hospice from their general prescribing recommendations.7 Anecdotally, hospice physicians have raised concerns that the CMS National Partnership has increased the difficulty of prescribing antipsychotics to hospice patients within nursing home facilities. There has been a call for CMS to consider excluding patients in hospice from the long-stay antipsychotic quality measure given concerns that it may impede access to this common component of the hospice toolkit.9

Among long-stay residents with ADRD enrolled in hospice, use of antipsychotic medications decreased significantly throughout the study period. Prescribing trends for other CNS-active medications among residents with ADRD enrolled in hospice remained largely stable without clear evidence of substitution. High rates of use of analgesics, antianxiety, and antidepressant medication use were observed among long-stay residents with ADRD in hospice from 2011–2017. There are limited results by which to compare our findings as CMS did not previously capture medication prescribing data for patients enrolled in hospice.30 Previous reports of medication use in hospice are limited to survey data,31 prescribing information from a single hospice organization,6 and do not show prescribing trends over time.32

Our analysis has several limitations. First, use of MDS assessments to ascertain medication data limits analysis to medication classes included in the MDS assessments and excludes medication use that occurs in between recorded MDS assessments. Therefore, we are unable to evaluate use of other CNS medication classes (e.g., such as antiepileptic or mood stabilizers) which may be substituted for antipsychotics, evaluate the use of specific agents, or determine change in medication dose.21 However, unlike other medication claims data such as Part D, MDS assessments do inform medication use as only medications received by nursing home residents are recorded in MDS assessments. Second, we do not know the prescribing indication for the medications in this analysis or whether medication prescribing was appropriate. Third, this analysis does not include patient-level outcomes from medication exposure to inform potential benefits versus harms of antipsychotic use among nursing home residents enrolled in hospice. Finally, our analysis ends in 2017 and does not capture the most recent prescribing trends.

CONCLUSIONS

Reductions in antipsychotic prescribing that occurred following the CMS National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes were widespread and appear to have impacted both intended (i.e., patients with dementia) and unintended (i.e., hospice enrollees) long-term care populations. The likelihood of antipsychotic treatment declined for patients enrolled in hospice, for whom such prescribing may have been deemed indicated by hospice physicians. This overall reduction may also reflect changes in nursing home and hospice prescribing practices as well as greater focus on use of non-pharmacologic treatment strategies. Nursing homes are an important location for the provision of end-of-life care and the drivers of potentially unintended reductions in antipsychotic use in hospice merits cautious monitoring to make sure that potentially appropriate use does not also decline.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1. Percent of long-stay nursing home residents prescribed antipsychotics by hospice enrollment status and dementia diagnosis (used for Figure 1a and 1b)

Supplementary Table S2. Percent of long-stay nursing home residents with dementia enrolled in hospice prescribed antipsychotics or other psychotropic medication (used for Figure 2)

Impact Statement:

We certify that this work is novel. This study provides the first national evaluation of reductions in antipsychotic prescribing among nursing home hospice residents.

Key Points:

The CMS National Partnership was associated with reductions in antipsychotic prescribing among nursing home residents enrolled in hospice.

Why Does this Paper Matter?

Initiatives aimed at reducing antipsychotic prescribing among long-term care residents with dementia may have also impacted prescribing among populations not originally intended including residents without dementia and those enrolled in hospice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding Source:

This work was supported by NIA P01AG027296 and R03AG060073.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have none to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Office of Inspector General U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare atypical antipsychotic drug claims for elderly nursing home residents. 2011. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-07e08e00150.pdf.AccessedAugust 29, 2020.

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS announces partnership to improve dementia care in nursing homes. 2012. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announces-partnership-improve-dementia-care-nursing-homes.AccessedMarch 23, 2020.

- 3.Medicare.gov. About Nursing Home Compare data. Available at: https://www.medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare/Data/About.html.AccessedOctober 21, 2020.

- 4.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164(3):321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, Mor V. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sera L, McPherson ML, Holmes HM. Commonly prescribed medications in a population of hospice patients. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2014;31(2):126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Mediaid Services. MDS 3.0 Quality Measures User’s Manual October 2020. Avialble at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/NHQIQualityMeasures.AccessedAugust 1, 2020.

- 9.Herndon C, Wahler R Jr., McPherson ML. Beers Criteria, the Minimum Data Set, and Hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(7):1519–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Data show National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care achieves goals to reduce unnecessary antipsychotic medications in nursing homes. 2017. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/data-show-national-partnership-improve-dementia-care-achieves-goals-reduce-unnecessary-antipsychotic.Accessed onOctober 1, 2020.

- 11.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes: Antipsychotic Medication Use Data Report October 2019. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/antipsychotic-medication-use-data-report-updated-01242020.pdf.Accessed onJune 1, 2020.

- 12.Hunnicutt JN, Tjia J, Lapane KL. Hospice Use and Pain Management in Elderly Nursing Home Residents With Cancer. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2017;53(3):561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCreedy E, Ogarek JA, Thomas KS, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set Agitated and Reactive Behavior Scale: Measuring Behaviors in Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(12):1548–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wysocki A, Thomas KS, Mor V. Functional Improvement Among Short-Stay Nursing Home Residents in the MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(6):470–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(11):M546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care. 2017;55(9):e68–e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirdes JP, Frijters DH, Teare GF. The MDS-CHESS scale: a new measure to predict mortality in institutionalized older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linden A Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. The Stata Journal 2015;15.2:480–500. [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Public Health Advisory: Deaths with Antipsychotics in Elderly Patients with Behavioral Disturbances. Published 2005. Available at: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170113112252/http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm053171.htm.Accessed onSeptember 1, 2020.

- 20.Zivkovic S, Koh CH, Kaza N, Jackson CA. Antipsychotic drug use and risk of stroke and myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):189–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maust DT, Kim HM, Chiang C, Kales HC. Association of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care With the Use of Antipsychotics and Other Psychotropics in Long-term Care in the United States From 2009 to 2014. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2018;178(5):640–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simmons SF, Bonnett KR, Hollingsworth E, et al. Reducing Antipsychotic Medication Use in Nursing Homes: A Qualitative Study of Nursing Staff Perceptions. Gerontologist. 2017;58(4):e239–e250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of Oral Risperidone, Haloperidol, or Placebo for Symptoms of Delirium Among Patients in Palliative Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(1):34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finucane AM, Jones L, Leurent B, et al. Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020;1:Cd004770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutherland A, Naessens K, Plugge E, et al. Olanzapine for the prevention and treatment of cancer-related nausea and vomiting in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;9(9):Cd012555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Essential Medicines in Palliative Care. Executive Summary. Published January 2013. Available at: https://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/19/applications/PalliativeCare_8_A_R.pdf.Accessed onJanuary 15, 2021.

- 27.Beller EM, van Driel ML, McGregor L, Truong S, Mitchell G. Palliative pharmacological sedation for terminally ill adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;1:Cd010206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray-Brown F, Dorman S. Haloperidol for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015(11):Cd006271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hui D, Frisbee-Hume S, Wilson A, et al. Effect of Lorazepam With Haloperidol vs Haloperidol Alone on Agitated Delirium in Patients With Advanced Cancer Receiving Palliative Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(11):1047–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Center for Medicare Chronic Care Policy Group. Medicare hospice payment reform: analysis of how the Medicare hospice benefit is used. 2015. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Hospice/Downloads/December-2015-Technical-Report.pdf.AccessedSeptember 15, 2020.

- 31.Dwyer LL, Lau DT, Shega JW. Medications That Older Adults in Hospice Care in the United States Take, 2007. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2282–2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchanan RJ, Choi M, Wang S, Huang C. Analyses of nursing home residents in hospice care using the minimum data set. Palliative Medicine. 2002;16(6):465–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Percent of long-stay nursing home residents prescribed antipsychotics by hospice enrollment status and dementia diagnosis (used for Figure 1a and 1b)

Supplementary Table S2. Percent of long-stay nursing home residents with dementia enrolled in hospice prescribed antipsychotics or other psychotropic medication (used for Figure 2)