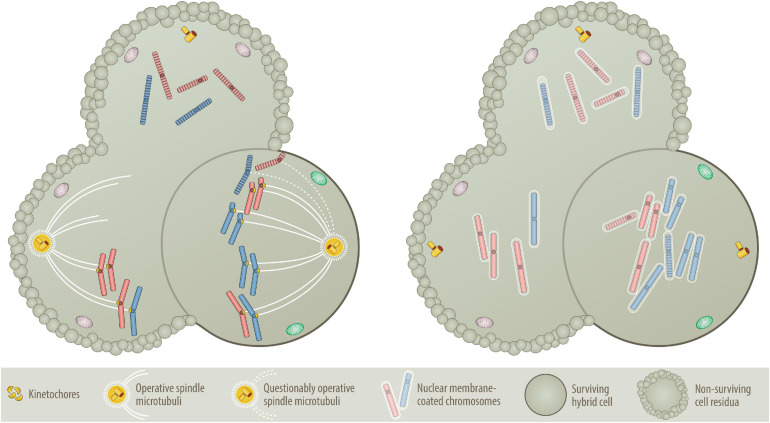

FIGURE 4.

Nondisjunction (Left) versus “micronuclei” fusion (Right) versions of aneuploidy formation. One of the central questions of the BNDA model is whether at all and how prematurely condensed G0/G1 chromosomes can be incorporated into the mitotic chromosome cluster. As illustrated on the left, prematurely condensed chromosomes have no kinetochores, which are deemed necessary to facilitate their attachment to the microtubular spindle network (Tanaka et al., 2005; Cimini, 2008; Thompson and Compton, 2011; Silkworth and Cimini, 2012). As essential components of the mitotic spindle apparatus these multiprotein structures assemble only at the centromeres of sister chromatids in mitosis, where they control, supervise and coordinate sister chromatid segregation (Tanaka et al., 2005; Cimini, 2008; Silkworth et al., 2009; Thompson and Compton, 2011; Silkworth and Cimini, 2012). One circumstantial evidence that can be put forward as an explanation is that at least in the accommodating cytoplasmic milieu of an oocyte, prematurely condensed G0/G1 chromatids of somatic cells can replace sperm-derived ones and attain their segregation competence even without preexisting kinetochores (Saadeldin et al., 2016). Although the vast majority of such semi-somatic zygotes are aneuploid, they nevertheless can even go through early steps of embryonic development (Saadeldin et al., 2016). A further supportive argument resides on the commonplace method that is used to clone animals, in which interphase nuclei of various differentiated donor cells are transferred into empty, enucleated oocytes (Wells, 2005; Wilmut et al., 2015). Importantly, both procedures work only with G0/G1 cells and best with quiescent nuclei of G0 cells (Wells, 2005; Wilmut et al., 2015; Saadeldin et al., 2016). Another kinetochore- and spindle-unrelated mechanism (illustrated on the right) that in a pure somatic setting offers perhaps a much more plausible explanation, relates to the dissolution and reformation process of interphase nuclei (Burke and Ellenberg, 2002; Stewart et al., 2007; Guttinger et al., 2009; Hetzer, 2010; Lu et al., 2011; Schooley et al., 2012). When interphase nuclei split up into individual chromosomes, they produce abundant nuclear membrane fragments that are temporarily stored in the endoplasmatic reticulum before they are reused for reassembling the newly formed segregated chromosomes sets into new nuclei again (Guttinger et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2011; Schooley et al., 2012). To achieve this, membrane fragments first coat the individual chromosomes, which only then agglomerate and coalesce into distinct nuclei again (Schooley et al., 2012). Such single chromosome micronuclei form the basis for the microcell-mediated transfer of exogenous chromosome material into host cells (Meaburn et al., 2005; Fenech et al., 2011), which even enabled the successful integration of entire intact human chromosomes 8, 13, 18 and 21 into human isogenic embryonic stem cells (Kazuki et al., 2014; Hiramatsu et al., 2019) as well as chromosomes 3, 7 and 13 into the karyotypic stable, mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancer cell line DLD-1 (Upender et al., 2004; Nicholson et al., 2015; Rutledge and Cimini, 2016; Wangsa et al., 2019). A missegregated micronucleus can also undergo massive shattering and restructuring before these pieces rejoin again and form a new single chromatid, which can then become part of the nucleus again. Although this process, chromothripsis, is a frequent phenomenon in cancer genomes, it is rare in aneuploid leukemias (Chen et al., 2015). Presuming that this encapsulating mechanism will not discriminate between mitotic and prematurely condensed chromosomes, I consider this the most likely way of how the latter can get mixed up with mitotic ones, even without the necessity of evoking a microtubular-machinery for this purpose. Likewise, this mechanism seems also a reasonable way to explain how the remaining prematurely condensed chromosomes can rejoin again and form at the same time the genomic basis of a second independent aneuploid neoplastic founder cell provided they constitute at least a full haploid set, as illustrated in Figure 2B. The evolving aneuploid hybrid cell in the example shown here contains heterozygous tetrasomic, homozygous trisomic and pentasomic chromosomes, whereas the two other potential fusion cell descendants lack an adequate combination of chromosomes and can therefore not survive.