Abstract

The Household Food Waste Questionnaire (van Herpen et al. 2019a) was developed and validated as an effective instrument to identify statistically significant differences between households and to distinguish trends in household food waste over time. The original instrument was validated using consumers sampled from several European countries. We conduct a pilot study with U.S. consumers using the revised questionnaire. We find that a sample of 150 online panelists provided sufficient statistical power to replicate standard findings from the literature that smaller households and older respondents generate less food waste, but not enough statistical power to identify a statistically significant week-to-week reduction in reported food waste among households who received a food waste message rather than a control message. Power analysis conducted via bootstrapping with the pilot data suggests a usable sample size of 180 per group is required. In our study, we adapted the questionnaire for use with consumers in the United States by:

-

•

Adjusting food category descriptions and converting food quantity benchmarks to units and amounts more familiar to U.S. consumers.

-

•

Refining several elements to the questionnaire, including the addition of a visual guide to help respondents better estimate food quantities.

-

•

Expanding the approach by adding a second follow up questionnaire that permits assessment of within household changes over consecutive weeks.

Keywords: Food waste, Food loss, Questionnaire, Intervention, Self-report, Experiment, Validation, Power analysis, Survey design

Graphical abstract

Specifications table

| Subject Area: | Economics and Finance |

| More specific subject area: | Household food waste |

| Method name: | Household Food Waste Questionnaire: U.S. Version |

| Name and reference of original method: |

Name: A validated survey to measure household food waste Reference: van Herpen, E., van Geffen, L., Nijenhuis-de Vries, M., Holthuysen, N., van der Lans, I., & Quested, T.E. [15]. A validated survey to measure household food waste. MethodsX, 6, 2767-2775. |

| Resource availability: | Data analysis software: STATA Original data and survey design in Qualtrics format available upon request. |

Method details

Policy makers continue to emphasize the multifaceted potential that reducing food waste holds for advancing sustainability goals through reductions in resources use, food insecurity, and greenhouse gas emissions. Multiple interventions have been suggested for reducing wasted food at the household level, though few have been robustly tested [7]. This lack of systematic evaluation stems, in part, from the cost and burden of collecting household-level data that is of sufficient quality and granularity to support statistical inference.

Questionnaires in which household members are asked to retrospectively recall the amounts and types of wasted food represent one of several popular methods of estimating household food waste. Other methods require participants to actively track food waste over a period of time, such as diary keeping (Tucker and Farrelly 2016, Diaz-Ruiz et al. 2018 [10,2]) or to coordinate with researchers to ensure waste is collected for subsequent analysis, such as waste compositional analysis [1,8,13]. Questionnaires are a low-cost approach that place less of a time burden on participants than diaries and, unlike waste stream analysis, do not require on-site coordination of waste collection. Hence, questionnaires can scale more easily than alternative methods, e.g., hold the potential to provide insights at a national scale [16].

The accuracy and reliability of questionnaires in capturing waste levels have been scrutinized as such survey-based approaches typically yield lower estimates of food waste than other methods [9,14,16]. This has led official bodies such as the European Commission [3] to omit surveys from the list of approved methods for assessing food waste.

However, van Herpen and colleagues [15] document a modification of standard questionnaire approaches that prompts participants a week prior to the arrival of a detailed questionnaire to monitor their food waste over the next week (pre-announcement). The authors demonstrate that their Household Food Waste Questionnaire (HFWQ) can differentiate across households with differing levels of food waste. This HFWQ reported approximately 639 grams of food waste per week per household, or around 43 percent less compared to using a diary (1122 grams per week per household), 39% less compared to using kitchen caddies, and 48% less compared to the waste composition analysis approach (1450 grams per week per household, [16]b) This is in line with previous findings, which indicated a 40% underreport of food waste through self-reporting [9]. While the method is still unable to document accurate absolute levels of food waste, it holds the promise to accurately distinguish differences in food waste between households and across time, and provides an important, scalable tool for documenting spatial and temporal variation in household food waste.

The purpose of this article is to describe an adaptation, refinement, and extension of the HFWQ suitable for U.S. consumers (HFWQ:US). Adaptation is necessary because the questionnaire was developed and tested in several European countries. Descriptions of food and food waste are inherently intertwined with culture, necessitating translation and adaptation of survey language and measurement units into relevant national contexts. We begin by describing our adaptation of the version published by van Herpen et al. [15]. We then describe several logical refinements and extensions to the questionnaire that may enhance its utility to researchers. We next share analysis from an Autumn 2020 pilot study that uses the HFWQ: US to test if standard between-household differences in food waste levels can be detected and if food waste messaging induces reductions in week-to-week waste levels reported by participating households. By adopting the HFWQ self-report survey method in the US setting, we aim not only to expand the adaptability of the method that has previously been proven validate in the Europe Union, but to improve the versatility of this approach by exploring the potential to use the expanded survey to measure the comparative efficacy of food waste reduction messages over a one-week period.

Original survey structure

The HFWQ features a brief communication (pre-announcement) followed by the primary questionnaire [15]. The pre-announcement tells participants to monitor the amounts of food and drink waste in their homes over the next week. It further clarifies that the focus is on wasted food and drink items that are or were once edible (not shells, bones and peels that are not normally consumed) and on food and drink consumed in their residence (including takeout consumed at home, but not waste that occurs during meals consumed away from home). It emphasizes that items should be considered waste even if they were composted or given to an animal.

The primary questionnaire arrives approximately 7 days later. It begins by reiterating the points made in the pre-announcement. It then lists 24 food and drink categories and prompts respondents to mark each category in which waste occurred during the past 7 days, plus a box that can be marked if no waste occurred in any category during the past 7 days. For each category chosen, a set of questions appears that prompts the respondent to choose one in an increasing sequence of quantity categories representing the amount wasted (e.g., less than 1 cup, 1 to 2 cups, 3 to 4 cups, 5 to 6 cups, more than 6 cups). Once chosen, participants are prompted to mark the status of the majority of food wasted in the category. The options include ‘completely unused food’, ‘partly used foods’, ‘meal leftovers’ or ‘leftovers after storing.’ Participants then proceed through the remaining categories that were selected as having any waste. Additional questions assessing participant characteristics, awareness, attitudes, etc., can be added to either the pre-announcement or main survey.

Survey adaptations and refinements for U.S. participants

Adaptation for an audience in the United States focused on revising: 1) food category names and 2) reference units and quantities for quantifying waste in each food category. These adjustments are summarized in Table 1. Estimates of total household food waste were calculated by translating each category's waste level into grams and summing across all categories. This requires two sets of assumptions. First, a number must be assigned for each category, e.g., ‘less than 1 cup’ = 0.5 cups, ‘1 to 2 cups’ = 1.5 cups, etc. Next, a weight in grams must be assigned to each quantity. For categories with items that have highly variable weight per unit of volume (e.g., within vegetables, a cup of raw asparagus weighs about 7 times more than a cup of raw chopped arugula), we assume the items thrown away mirror the U.S. profile of items produced (USDA 2021) [12]. Table 2 lists the gram weight for each quantity category across the 24 food categories.

Table 1.

U.S. adaptations to the household food waste questionnaire by food category.

| Category Names | Units and Amounts | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Van Herpen et al. (2019) | U.S. Adaptation | Van Herpen et al. (2019) | U.S. Adaptation |

| Fresh Vegetables and Salads | -* | Serving spoon (50g) | Cups (153g) ** |

| Non-fresh vegetables | - | Serving spoon (50g) | Cups (130g) ** |

| Fresh Fruit | - | Piece (100g) | Pieces (130g) ** |

| Non-fresh Fruit | - | Piece (80g) | - |

| Potatoes | - | Serving spoon (60g) | Cups (153.6g) |

| Potato products (fries, chips, baby or precooked potatoes, etc.) | Potato products (fries, hash browns, etc. - report potato chips under 'salty snacks') | 10 fries/piece (50g) | Cups (128g) |

| Pasta | - | Serving spoon (50g) | Cups (128g) |

| Rice and remaining grains (including wraps, couscous, etc.) | Rice and other grains (including wraps, couscous, etc.) | Serving spoon (60g) | Cups (153.6g) |

| Beans | - | Serving spoon (50g) | Cups (184g) ** |

| Meat (please report cold meat slices at “bread toppings”) | Meat (please report deli meat under 'sandwich ingredients') | Portion (150g) | - |

| Meat substitute | Meat alternatives | Portion (150g) | - |

| Fish | Fish | Portion (150g) | - |

| Bread toppings (cold meats slices, cheese slices, sweet topping, etc.) | Sandwich ingredients (deli meats, cheese slices, relishes, etc., but report lettuce and vegetables under 'fresh vegetables and salads') | Portion (20g) | - |

| Bread | - | Slice (35g)/Loaf (800g) | - |

| Cereals (muesli, granola, oat, brinta, etc.) | Cereals (breakfast cereal, corn meal, oats, etc.) | Portion (40g) | Cups (128g) |

| Yoghurt, custard, etc. | Yogurt, custard, etc. | Portion (150g) | Cups (240g) |

| Cheese (cheese cubes, French cheese, sprinkle cheese. Excluded: cheese as bread topping) | Cheese (report cheese slices under 'Sandwich ingredients') | Cube (10g) | Cups (128g) |

| Eggs | - | Egg (60g) | - |

| Soups/curry | Soups/stews | Ladle (150g)/Liter (1000g) | Cups (240g) |

| Sauce (ketchup, mayonnaise, cocktail sauce, etc.) | Condiments and sauces (ketchup, mayonnaise, cocktail sauce, etc.) | Tablespoon (14g)/Jar (630g) | - |

| Candy / cookies / granola bars / chocolate bars | - | Portion (20g) | - |

| Crisps / nuts | Salty snacks (chips, nuts, pretzels, etc.) | Portion (20g) | - |

| Non-alcoholic beverages (milk, juice, soda. Excluded: water, tea, coffee, diluted syrup) | - | Glass (250g)/Liter (1000g) | Cups (240g)/Quart (950g) |

| Alcoholic beverages | - | Beer glass (300g)/Liter (1000g) | Cups (240g)/Quart (950g) |

Table 2.

Weight in grams by quantity category for all 24 food categories.

| Category: Quantity→ Product ↓ |

1* | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh Vegetables | 76.5 | 229.5 | 535.5 | 841.5 | 1071 |

| Non-fresh vegetables | 65 | 195 | 455 | 715 | 910 |

| Fresh Fruits | 32.5 | 65 | 130 | 520 | 650 |

| Non-fresh Fruits | 20 | 40 | 80 | 240 | 400 |

| Potatoes | 76.8 | 230.4 | 537.6 | 844.8 | 1075.2 |

| Potato products | 64 | 192 | 448 | 704 | 896 |

| Pasta | 64 | 192 | 448 | 704 | 896 |

| Rice | 76.8 | 230.4 | 537.6 | 844.8 | 1075.2 |

| Beans | 92 | 276 | 644 | 1012 | 1288 |

| Meat | 37.5 | 150 | 375 | 675 | 900 |

| Meat alternatives | 37.5 | 150 | 375 | 675 | 900 |

| Fish | 37.5 | 150 | 375 | 675 | 900 |

| Sandwich ingredients | 5 | 20 | 50 | 90 | 120 |

| Bread | 18 | 70 | 400 | 800 | 1600 |

| Cereal | 64 | 192 | 448 | 704 | 896 |

| Yogurt | 120 | 360 | 840 | 1320 | 1680 |

| Cheese | 64 | 192 | 448 | 704 | 896 |

| Eggs | 30 | 60 | 150 | 270 | 360 |

| Soups | 60 | 180 | 360 | 840 | 1200 |

| Condiments | 7 | 28 | 84 | 315 | 1260 |

| Candy | 5 | 20 | 50 | 90 | 120 |

| Salty Snacks | 5 | 20 | 50 | 90 | 120 |

| Non-alcoholic beverages | 60 | 240 | 475 | 950 | 1900 |

| Alcoholic beverages | 60 | 240 | 475 | 950 | 1900 |

*See exact questionnaire language in supplemental materials for descriptions of each quantity category by food category.

Questionnaire refinements and expansions

We refine and add several components to the questionnaire implemented in the U.S. pilot study described below. First, during the pre-announcement, after informing respondents to monitor their food discards during the upcoming week, we ask them to answer a question to assess their comprehension of the instructions. Second, during the primary questionnaire, we show respondents a visual aid immediately before the quantity estimation questions to help respondents estimate food amounts more accurately (Fig. 1). Third, in the primary questionnaire, we permit respondents to indicate if any issues may have caused an unusual amount of food to be discarded during the past week (unexpected guests, eating out unexpectedly, tried a new recipe, etc.).

Fig. 1.

Visual aid for estimating food quantities.

Fourth, we invite participants to complete a second primary questionnaire that is administered approximately a week after the completion of the first primary questionnaire. The second primary questionnaire repeats all food waste measurement questions, thus providing estimates of food waste over two consecutive weeks.

Pilot study: testing between subject differences and food waste reduction messages

The study was approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Review Board, and all respondents provided informed consent to participate. Qualtrics was utilized for both the design and implementation of the online survey. Respondents were contacted via an email or text (according to panelists’ preferences previously communicated to Qualtrics) that provided them with an overview of the study and a web link to participate. They were asked to consider taking a survey being conducted to “…understand how food waste behavior in the U.S. at the household level responds to several types of treatments and different socio-demographic characteristics” and were offered compensation for participation. Inclusion criteria included (a) age 18 or older, (b) responsibility for at least half of household food preparation, (c) access to the internet, and (d) willingness to complete initial baseline (pre-announcement) survey and two follow up (primary) surveys.

For the purposes of this pilot study, two additional inclusion criteria were enforced. Recruits had to be part of younger (18 – 35) or older (55+) age cohorts and had to live in small (1-2 people) or large (5+ people) households. Past research [4] suggests age and household size are among the most robust characteristics when predicting levels of household food waste. These additional screening criteria were chosen to maximize our chances of identifying significant differences in food waste between households that differed in terms of household size and participant age within our limited sample size.

Vendors affiliated with Qualtrics distributed the surveys to lists of respondents from across the continental United States who were willing to participate in surveys of all types and met the inclusion criteria. Respondents participated in several screening questions as part of the pre-announcement survey. All who passed the screener questions, provided consent, and received the pre-announcement messages were invited to participate in the primary questionnaire. Participants who completed both the pre-announcement and primary questionnaire were invited to complete the second primary questionnaire (the distribution gap between surveys ranged from 5 to 7 days). From the 150 respondents who completed the pre-announcement, 124 took the primary questionnaire with 118 providing sufficient responses to calculate a household food waste quantity (21.3% attrition rate between pre-announcement and primary questionnaire). Two additional participants were lost between the first and second primary questionnaires, yielding 116 usable values for changes in food waste between the two primary questionnaires (22.7% attrition rate from pre-announcement to the second primary questionnaire).

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 3. Like many online surveys, some demographic segments are underrepresented, including respondents who report less formal education or income and those who identify as Black. Attrition was greater among Black participants, younger participants, and those from the highest income category. Older participants were significantly less likely to attrite while Black participants were significantly more likely to attrite (see supplemental materials for regression results). We note that attrition and representativeness may have differed if we had not purposefully excluded respondents in the middle age and household size categories. Sample self-selection on demographic and attitudinal characteristics is likely an issue for surveys as well as other residential food waste measurement approaches that require participant consent (e.g., diaries and waste analysis).

Table 3.

Summary statistics from pilot sample.

| Variable | Pre-announcement n=150 | 1st Primary Questionnaire n=118 | 2nd Primary Questionnaire n=116 | US (2019) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-identified Racial Identification | ||||

| White | 81.3% | 83% | 82.8% | 72% |

| Black | 6.7% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 12.8% |

| Asian | 5.3% | 6.8% | 6.9% | 5.7% |

| Other | 6.7% | 6.8% | 6.9% | 9.5% |

| Age | ||||

| 18-24 | 6.7% | 4.2% | 4.3% | 11.8% |

| 25-34 | 19.3% | 16.1% | 16.4% | 18.0% |

| 35-54 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 32.3% |

| 55-64 | 16.7% | 16.1% | 16.4% | 16.6% |

| 65 and older | 57.3% | 63.6% | 62.9% | 21.2% |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 50.7% | 51.7% | 51.7% | 49.2% |

| Female | 49.3% | 48.3% | 48.3% | 50.8% |

| Highest education level | ||||

| Less than high school graduate | 2% | 0% | 0% | 9.6% |

| High school graduate, diploma or GED | 16.7% | 20.2% | 19.8% | 24.2% |

| Some college or Associate degree | 31.3% | 30.7% | 30.2% | 30.4% |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 50% | 49.1% | 50% | 35.8% |

| Total household food waste (g/week) (std dev) | – | 737.12 (1887.76) | 532.35 (931.97) | – |

| Per person food waste (g/week) (std dev) | – | 430 (1610.485) | 308.85 (819.97) | – |

| Annual household income | ||||

| Less than $50,000 | 22.7% | 31.4% | 22.4% | 38.4% |

| $50,000 to $99,999 | 44.7% | 45.8% | 45.7% | 30.2% |

| $100,000 or more | 32.6% | 22.8% | 31.9% | 31.4% |

| Average household size (std dev) | 2.48 (1.7) | 2.4 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.69) | 2.52 |

| Average # of children < 18 (std dev) | 0.48 (1) | 0.39 (1) | 0.4 (1.01) | 0.57 |

* [11].

Statistical analysis was performed in Stata (version 14). Statistical significance is established at the 5% level with significance at the 10% level deemed marginal significance. Differences across groups during a single time period are analyzed using a censored regression to account for a nontrivial portion of respondents who report zero waste (Stata routine ‘tobit’). Differences across time are calculated as the weight from the second primary questionnaire minus the weight from the first primary questionnaire. These values are analyzed using a censored regression implemented via a different Stata command (‘intreg’), which permits customization of which observations are censored. When analyzing differences across time, censoring occurs when a respondent reports a positive amount on the first primary questionnaire (week 1) and zero waste on the second primary questionnaire (week 2). For example, in our pilot, a respondent may have had a positive amount of waste in week 1 and then changed behavior to eliminate waste in week 2. However, the amount of waste reduction possible is censored by the amount of waste created in week 1. Finally, three observations are deemed outliers as their reported quantities have z-scores that exceed |3| (+5.66, +7.67, +8.19); these are omitted from all regression analyses, but not from the summary statistics.

Pilot experimental design

As part of the pilot, we embed two experimental elements. First, we randomly assigned the language on the pre-announcement survey instructions that prompts respondents to monitor their actions during the upcoming 7 days. Half were randomly assigned to the standard HFWQ message telling participants to “…pay attention to the amounts of foods that you throw away because they are past date, spoiled or are no longer wanted for other reasons.” The remainder were simply told to “…pay close attention to the food and drinks you use in your home…” (see Fig. 2). We hypothesize that adding specific language regarding waste may trigger participants to create and/or report less waste on the follow up survey than the more general language to monitor food and drink use.

Fig. 2.

Messages randomly assigned during study.

Second, upon completion of the first primary questionnaire, we randomly assign participants to one of two messages (Fig. 2). A treatment message focuses on food waste while a placebo message focused on screen time for children. Each message was immediately followed by three questions to assess comprehension and stimulate engagement with the information.

Pilot results

Finding 1: absolute reported levels of food waste are low

In week 1 (captured by the first primary questionnaire), the average household waste reported is 736 g/week (1.62 pounds) or 430 g/week (0.95 pounds) on a per person basis; 31.4 percent report zero waste. Waste declines to an average of 532 g/week (1.17 pounds) in week 2, with 31.0 percent reporting zero waste. These amounts are less than the 2.5 pounds per person estimated among households in three U.S. cities in 2017 using a diary approach corrected for underreporting rates that were calibrated using contemporaneous waste stream analysis [6]. However, we must remember that our survey sample omitted middle-sized households with heads in the middle age categories (both groups tend to have middling amounts of waste compared to the included groups), which makes comparisons to broader samples more tenuous. Given this caveat, our results from weeks one and two bracket the amount reported in the original Household Food Waste Questionnaire (639 grams per week per household) administered in Europe. Hence, our findings are consistent with van Herpen et al.’s [16] assessment that questionnaires like the HFWQ and its US counterpart likely underestimate the absolute level of wasted food produced by households.

Finding 2: expected between-group differences are significant

Even with the sample size available, we were able to replicate differences in waste by respondent age and household size. Younger respondents report significantly greater waste than older respondents while small households report marginally significantly less waste than large households (Table 4, first two rows). Bootstrapping the data suggests a sample size of 56 (28 per group) to detect a significant difference in food waste between young and old participants while a sample size of 86 (43 per group) is recommended to detect a significant difference in food waste between small and large households.

Table 4.

Tobit regression coefficients for week 1 household food waste quantity.

| Variable | Coefficient (Standard Error) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age 18 - 35 (vs. Age 55+) | 583.62 (261.75) |

0.028 |

| 1 or 2 Household Members (vs. 5+) | -443.44 (244.96) |

0.073 |

| Pre-announcement instructions: Monitor discarded food and drink (vs. monitor food and drink use) | 100.60 (178.71) |

0.575 |

Notes: n=114. Chi-square(3) = 12.73 (p = 0.0053). 37 values are left-censored. Robust standard errors are reported.

Finding 3: pre-announcement monitoring instructions focused on food waste are not statistically significant

Respondents who were given the standard pre-announcement instructions to monitor food and drink discards over the next 7 days reported about 100 g more waste than those who were simply told to pay attention to their food and drink use over the next 7 days (Table 4, last row). However, this difference was not statistically significant. Hence, the hypothesis that mentioning terms for waste in the monitoring instructions induces lower reported amounts (e.g., actual reductions in waste or reductions in reported waste) is not supported in this pilot sample.

Finding 4: food waste message testing requires a larger sample size

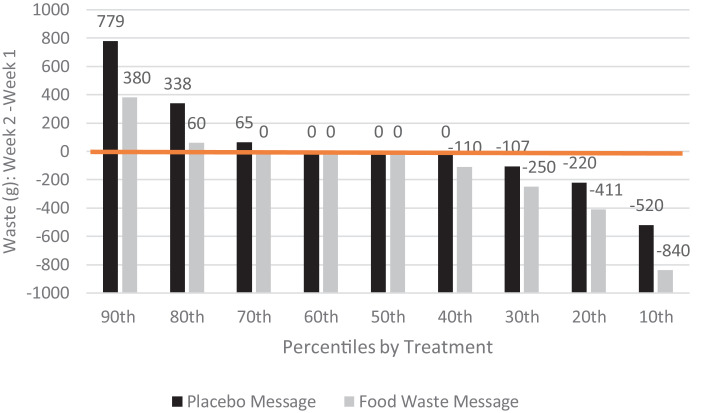

Fig. 3 shows that those respondents who received the food waste message reported a week-over-week reduction in reported waste that was greater than or equal to the reduction reported by those who received the placebo message at every decile of the sample distribution. There could be some reduction in reported waste level even in the absence of any messaging focused on food waste, but we only observed close to marginally significant week-over-week reduction among those receiving the placebo message (Table 5, p = 0.109). Those receiving the food waste message responded with a highly significant reduction (p = 0.006). However, the difference in difference coefficient, while of the expected negative sign, was not statistically significant (p = 0.352), suggesting the current sample size was insufficient to identify a statistically significant treatment effect.

Fig. 3.

Change in weekly waste levels by randomly assigned message.

Table 5.

Difference in difference estimates: food waste message effect.

| Effect | Censored Regression Coefficient | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo: Week 2 – Week 1 | −159.79 (99.79) |

0.109 |

| Food Waste: Week 2 – Week 1 | −392.58 (142.74) |

0.006 |

| Difference in Differences | −151.02 (162.42) |

0.352 |

The effect size of the food waste message is about 25% (the absolute value of the difference in difference coefficient of 151 g is about 25% the size of the week 1 average waste of 594.6 g created by the group who received the food waste message). This suggests that a larger sample size would be needed to establish a statistically significant result. By bootstrapping the original data, we recommend that researchers interested in establishing significance of an intervention with a 25% effect size at the 5% (10%) level have a usable sample of 480 (360) respondents. Given an attrition rate of 24% (which includes both attrition and the incidence rate of outliers), this suggests enrolling about 630 (474) participants or about 315 (237) enrollees per message (treatment and placebo). We note that the bootstrap results and these suggested group sizes might have been different had the sample included all age groups and all household size groups rather than omitting the middle age and size groups as was done in this pilot study.

Discussion and conclusions

We adapt the Household Food Waste Questionnaire for U.S. consumers and suggest several possible refinements and extensions. In our pilot test, this adapted questionnaire identifies statistically significant differences in reported waste amounts that are expected between households of different sizes and respondents of different ages populated by those of different ages, all within a sample of modest size for an online panel survey (150 recruits, 118 completes, and 114 usable responses). When the primary questionnaire is used within households over consecutive weeks, we observe very little additional attrition of sample size between the administration of the first and second primary questionnaire. However, the modest sample size from our pilot was not sufficient to identify a 25% effect size associated with the food waste reduction message we tested. Bootstrap analysis suggests a usable sample size of 360 (180 each for the treatment and control condition) is needed to identify marginally statistically significant reductions associated with such interventions, which translates to about 237 per group given the attrition and outlier rates observed among the online consumer panel used in this pilot study.

One key cause of this issue as mentioned in van Herpen's et al.’s [16] systematic review is that survey-based food waste measurement draws upon respondent memory to recall past events, which is not always reliable. Therefore, they proposed using a survey pre-announcement as a strategy to mitigate under-reporting ([16]b). Because respondents were not monitored when taking the survey, motives such as social desirability to reduce food waste, may still prevent truth telling, and respondents may report a lower amount of food waste. To our knowledge, no previous work has isolated the effect of social desirability on reported amounts of food waste, though the effect of social desirability on self-reported food intake is well documented [5].

Another key discussion point remains around how to interpret week-to-week reductions in reported food waste amounts that occur in response to researcher provided messaging. One hypothesis is that such changes represent true reductions spurred by the food waste message, while at the other extreme, it may represent merely a reduction in reported waste that is independent of actual behavior. The fact that the group in our pilot study who received a placebo message responded with reductions in weekly waste that bordered marginal significance suggests that the act of self-monitoring may trigger some social desirability response. The food waste message trends toward inducing more change, though whether this represents a larger social desirability response or a larger actual response in food waste reduction will require verification via a second independent data stream that does not involve self-reporting. Without another form of simultaneous independent measurement to validate the self-reports, we are unable to answer this definitively with the data at hand.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors recognize helpful feedback from Aishwarya Badiger, Xiaoyi Fang, Dennis Heldman, Ran Li and Danyi Qi. The authors recognize funding from the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center (project OHOA1632) and USDA-NIFA (#OHO01419).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.mex.2021.101377.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Dennison G.J. A socio-economic based survey of household waste characteristics in the City of Dublin, Ireland. I. Waste composition. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 1996;17(3):227–244. doi: 10.1016/0921-3449(96)01070-1. 1996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz-Ruiz R. Moving ahead from food-related behaviours: an alternative approach to understand household food waste generation. J. Cleaner Prod. 2017;172:1140–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.148. 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commission European. Commission delegated decision (EU) 2019/1597 of 3 May 2019 supplementing Directive 2008/98/EC of the European parliament and of the council as regards a common methodology and minimum quality requirements for the uniform measurement of levels of food waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019. 2019;248:77–85. https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/3/2019/EN/C-2019-3211-F1-EN-ANNEX-1-PART-1.PDF Annex 3. Availble online at. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hebrok M., Boks C. Household food waste: drivers and potential intervention points for design: an extensive review. J. Cleaner Prod. 2017;151:380–392. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hebert J.R., Clemow L., Pbert L., Ockene I.S., Ockene J.K. Social desirability bias in dietary self-report may compromise the validity of dietary intake measures. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1995;24(2):389–398. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoover, D., & Moreno, L. C. (2017). “Estimating quantities and types of food waste at the city level. Natural Resources Defense Council.” Available online at: https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/food-waste-city-level-report.pdf

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2020. A National Strategy to Reduce Food Waste at the Consumer Level. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parizeau K., von Massow M., Martin R. Household-level dynamics of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours in Guelph, Ontario. Waste Manage. 2015;35:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quested Ingle, R., Parry A. Household food and drink waste in the United Kingdom 2012. WRAP. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker C.A., Farrelly T. Household food waste: the implications of consumer choice in food from purchase to disposal. Local Environ. 2015;21(6):682–706. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2015.1015972. 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Census Bureau. (2020). “America's families and living arrangements: 2020.” The United States Census Bureau, www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/families/cps-2020.html.

- 12.US Department of Agriculture (2021). “Food Availability (Per Capita) Data System. Economic Research Service.” Available online at: www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-availability-per-capita-data-system/food-availability-per-capita-data-system/#Food%20Availability.

- 13.Van Der Werf P., Seabrook J.A., Gilliland J.A. The quantity of food waste in the garbage stream of southern ontario, canada households. PLoS One. 2018;13(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Dooren Corné. Measuring food waste in Dutch households: a synthesis of three studies. Waste Manage. (Oxford) 2019;94:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.05.025. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Herpen E., van Geffen L., Nijenhuis-de Vries M., Holthuysen N., van der Lans I., Quested T.E. A validated survey to measure household food waste. MethodsX. 2019;6:2767–2775. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2019.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Herpen E., van der Lans I.A., Holthuysen N., Nijenhuis-de Vries M., Quested T.E. Comparing wasted apples and oranges: an assessment of methods to measure household food waste. Waste Manage. (Oxford) 2019;88:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.