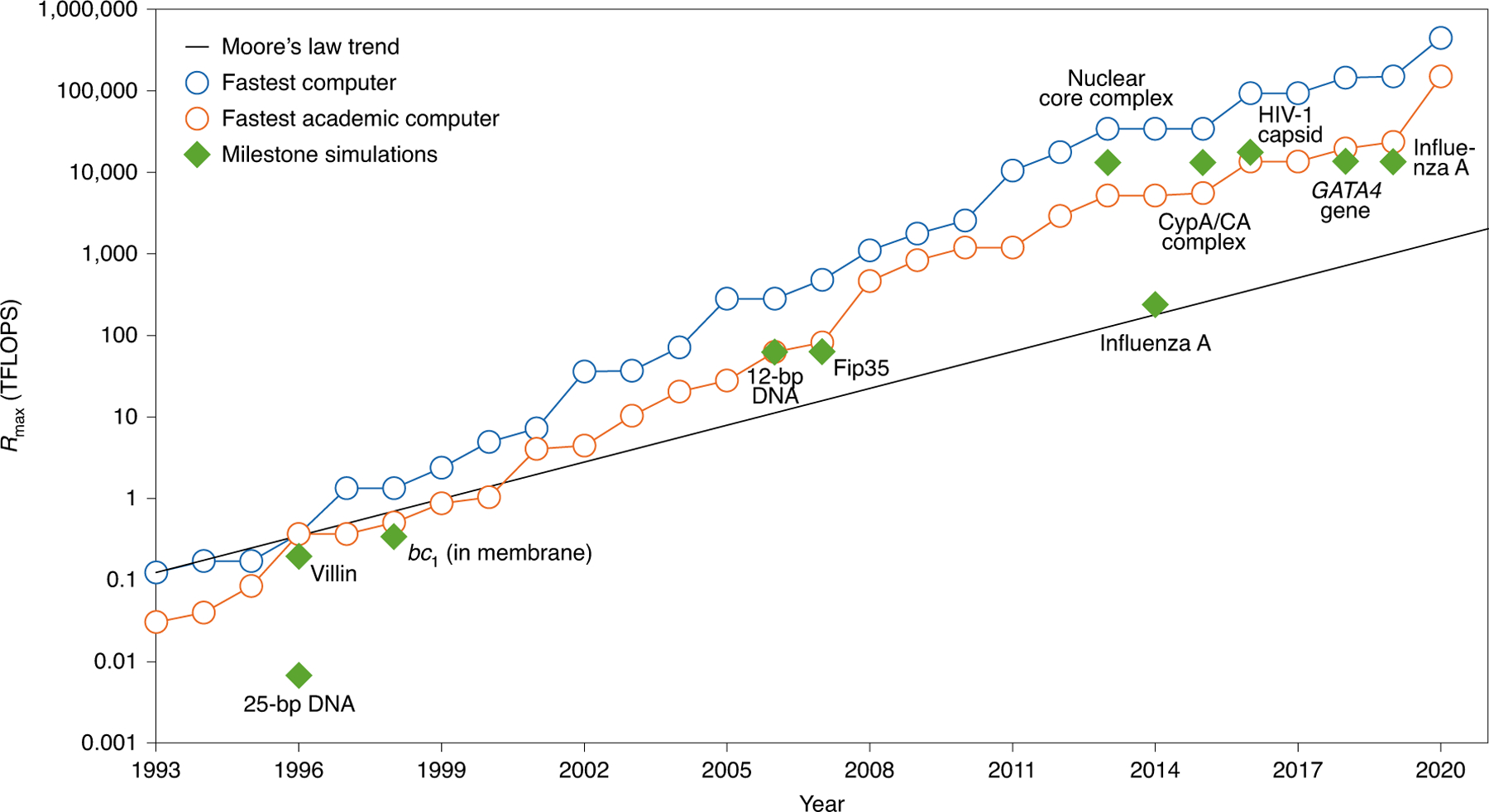

Fig. 2 |. Performance of landmark simulations compared with the world’s fastest supercomputers and moore’s law trend.

Plot of the computational system ranked first (blue) and the highest ranked academic computer (orange) as reported in Rmax according to the LINPACK benchmark as assembled in the Top500 supercomputer lists (www.top500.org). Rmax is the unit used to define computer performance in TFLOPS (trillion floating point operations per second). Landmark simulations (green diamonds) are dated assuming calculations were performed about a year before publication, except for the publications in 1998, which we assumed were performed in 1996. These include, from 1996 to the present, 25-bp DNA using National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) Silicon Graphics Inc. (SGI) machines144; villin protein145 using the Cray T3E900; bc1 membrane complex146 using the Cray T3E900; 12-bp DNA147 using MareNostrum/Barcelona; Fip35 protein148 using NCSA Abe clusters; nuclear core complex151 using Blue Waters; influenza A virus152 using the Jade Supercomputer; CypA/CA complex154 using Blue Waters; HIV-1 capsid7 using Titan Cray XK7; GATA4 gene39 using Trinity Phase 2; and influenza A virus H1N136 using Blue Waters. As Blue Waters has opted out of the Top500, we use estimates of sustained system performance/sustained petascale performance (SSP/SPP) from 2012 and 2020. For system size and simulation time of each landmark simulation, see Fig. 1.