Key Points

Question

What communication strategies do oncologists use that are associated with building and sustaining therapeutic alliance in the context of advancing pediatric cancer?

Findings

In this qualitative study, analysis of 141 disease reevaluation discussions representing 17 patient-parent dyads revealed 28 unique approaches used by oncologists that were associated with fostering therapeutic alliance. Ultimately, 7 themes emerged as strategies associated with optimizing therapeutic alliance: human connection, empathy, presence, partnering, inclusivity, humor, and honesty.

Meaning

In this study, pediatric oncologists used diverse communication approaches to deepen connections across advancing illness, with 7 core themes supporting a framework for future clinical and research work to strengthen therapeutic alliance among oncologists, patients, and families.

Abstract

Importance

Therapeutic alliance is a core component of patient- and family-centered care, particularly in the setting of advancing cancer. Communication approaches used by pediatric oncologists to foster therapeutic alliance with children with cancer and their families are not well understood.

Objectives

To identify key oncologist-driven facilitators associated with building and sustaining therapeutic alliance in the setting of advancing pediatric cancer and to develop a framework to guide clinical practice and future investigation of therapeutic alliance.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this qualitative study, serial disease reevaluation discussions that occurred in the clinic, inpatient hospital, or off campus via telephone were recorded among pediatric oncologists, patients with high-risk cancer, and their families across 24 months or until death, whichever occurred first, from 2016 to 2020. This analysis focused on recorded discussions for pediatric patients who experienced progressive disease during the study period. Content analysis was conducted across recorded dialogue to derive inductive codes and identify themes. Participants were patient-parent dyads for whom a primary oncologist projected the patient’s survival to be 50% or less, all family members and friends who attended any of their recorded disease reevaluation conversations, and their oncologists and other clinicians who attended the recorded discussions.

Results

A total of 33 patient-parent dyads were enrolled and followed longitudinally. From this cohort, 17 patients experienced disease progression during the study period, most of whom were female (11 [64.7%]) and White (15 [88.2%]) individuals. For these patients, 141 disease reevaluation discussions were audio recorded, comprising 2400 minutes of medical dialogue. Most children (14 [82.4%]) died during the study period. A median of 7 disease reevaluation discussions per patient (range, 1-19) were recorded. Content analysis yielded 28 unique concepts associated with therapeutic alliance fostered by oncologist communication. Ultimately, 7 core themes emerged to support a framework for clinician approaches associated with optimizing therapeutic alliance: human connection, empathy, presence, partnering, inclusivity, humor, and honesty.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this qualitative study, pediatric oncologists used diverse communication approaches associated with building and deepening connections across advancing illness. These findings offer a framework to support clinical and research strategies for strengthening therapeutic alliance among pediatric oncologists, patients, and families.

This qualitative study identifies key communication strategies used by oncologists to build and sustain therapeutic alliance with children with advancing cancer and their families, developing a framework to inform clinical practice and future investigation of therapeutic alliance.

Introduction

Patients with cancer and their families experience profound physical, psychological, and existential suffering across the illness trajectory.1,2,3,4 Development of therapeutic alliance between the patient or family and the oncologist may help ease the pain.5,6,7 Therapeutic alliance refers to the nature and strength of an affective bond between the patient or family and the clinician in collaboration toward shared goals.8,9,10,11 Among adult patients with advanced cancer, a strong therapeutic alliance with the oncologist has been associated with emotional acceptance of terminal illness and decreased invasive interventions at end of life.5 For young adults with cancer, the patient-oncologist alliance also has been shown to be protective against suicidal ideation.12 In addition, a positive patient-oncologist therapeutic alliance appears to benefit caregivers of adult patients with cancer across the illness course and during bereavement; more specifically, a patient’s report of a strong therapeutic alliance has been shown to be associated with a caregiver’s report of better social function, health-related quality of life, and emotional well-being following the patient’s death.6

As proposed by the National Cancer Institute13 and further validated in pediatric cancer,14 relationship building is considered one of the core functions of patient-centered communication.15 Most parents of children with cancer form trusting relationships with their child’s oncologist, and development of trust is associated with parent perception of high-quality physician communication.16 Fostering therapeutic alliance through patient-centered communication is particularly critical in the context of cancer relapse or progression, when children and families navigate stressful decisions.17 Unfortunately, poor outcomes have been shown to threaten therapeutic alliance, with parents reporting decreased trust in oncologists in the setting of advancing disease.16

Although high-quality oncologist communication is known to be important for therapeutic alliance,16 specific communication approaches used by oncologists to facilitate therapeutic alliance in pediatric cancer are not well understood. The U-CHAT (Understanding Communication in Healthcare to Achieve Trust) trial was designed to better understand the evolution and impact of communication across the advancing pediatric cancer trajectory.18 In this prospective, longitudinal study, serial disease reevaluation conversations among pediatric oncologists, patients with high-risk cancer, and their families were audio recorded across the illness course to the time of death. The primary aim of this study was to characterize the evolution of communication strategies used by pediatric oncologists across advancing illness. In this article, we present the findings from a secondary aim of that study: to identify and describe oncologist approaches for promoting therapeutic alliance, with the goal of developing a framework to organize emerging constructs and better understand potential facilitators for alliance to target in future research.

Methods

The protocol for this qualitative study was developed by an interdisciplinary team of pediatric oncology and hospice and palliative medicine experts in collaboration with a bereaved parent steering council; it was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. Data were collected between 2016 and 2020. We present study methods and findings following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) reporting guideline and checklist.19 All participants provided written or verbal informed consent that was obtained in a manner consistent with the Common Rule requirements. No one received compensation or was offered any incentive for participating in this study.

Details about the study protocol and feasibility and acceptability metrics for enrollment and capture of longitudinal data have been previously published.18,20 In brief, we enrolled a convenience sample of 6 pediatric oncologists who provided care to patients with solid tumors at an academic pediatric cancer center and obtained verbal informed consent. We then enrolled 4 to 6 patient-parent dyads with poor prognoses per oncologist. Eligible patients were aged 0 to 30 years, diagnosed as having non–central nervous system solid tumors, and considered to have poor prognosis, with the primary oncologist estimating survival of 50% or lower. Eligible parents or guardians were legal caregivers aged 18 years or older with English language proficiency who planned to be present for disease reevaluation discussions. Eligible patient-parent dyads were identified by the research team through review of outpatient clinic schedules and institutional trial lists, and permission to approach dyads was requested from the primary oncologist. A research team member obtained written informed consent from patients and caregivers during a clinic visit that did not include a disease reevaluation discussion; patients aged 12 years or older provided formal assent, and patients aged 18 years or older and parents provided consent. Demographic and disease-related information were extracted from the electronic medical record.

Patient-parent dyads were followed prospectively, with serial disease reevaluation discussions among patients, their family members and friends, and oncologists and other clinicians recorded in the clinic, hospital, or off campus via telephone across the illness course until death or 24 months from disease progression on study, whichever occurred first. The present work focuses on analysis of recorded discussions for dyads who experienced progressive disease during the study period.

To characterize key components of therapeutic alliance building in advancing pediatric cancer, we performed content analysis of recorded medical dialogue. We wanted to approach the data with openness to allow the dialogue to inform the findings; however, we also started with a priori constraints that shaped the lens through which we assessed the data (ie, we wanted to focus on clinician behaviors that served as potential facilitators of therapeutic alliance), precluding use of a traditional grounded theory approach. A research team representing medical and nursing perspectives across pediatric oncology and palliative medicine (Table 1) reviewed the literature related to therapeutic alliance in oncology; finding little consensus for fundamentals of alliance building in pediatric cancer care, we used an inductive approach21 to identify oncologist communication approaches to foster affective bonds with patients and families. Two researchers (E.C.K. and S.R.) repetitively listened to audio recordings, conducted extensive memo writing, and used raw data to inform development of codes, code definitions, and salient examples related to therapeutic alliance building.22 Additional researchers (C.W. and J.N.B.) reviewed recorded content and provided feedback in iterative cycles of codebook development. As facilitators were identified, we reviewed existing frameworks when possible to help codify concepts. For example, for expressions of empathy, we referenced the naming, understanding, respecting, supporting, and exploring framework for navigating emotions.23,24 However, through the processes of memo writing and inductive code development, we created definitions for each code based on the concepts emerging from the dialogue. The codebook was finalized following deep review of sufficient raw data to reach saturation, with no new therapeutic alliance concepts emerging from the recorded dialogue. The codebook is presented in Table 2.

Table 1. Research Team Attributes and Qualifications.

| Author | Attributes and qualifications |

|---|---|

| E.C.K. | Female physician-scientist with a medical degree, a master’s degree in public health, graduate-level training in qualitative research methods with a focus on communication science, and clinical training and practice in pediatric hematology-oncology and hospice and palliative medicine |

| S.R. | Female nurse-scientist with a master’s degree in public health, graduate-level training in qualitative research methods, and clinical training and practice as a pediatric oncology nurse and an advanced practice provider |

| C.W. | Female research associate with formal MAXQDA training and expertise in qualitative research methods |

| M.E.L. | Female physician-scientist with a medical degree, graduate-level training in qualitative research methods with a focus on communication science, and clinical training and practice in pediatric neurology and neonatal neurology |

| K.A. | Female scientist with a PhD degree in qualitative research methods and extensive experience with teaching and conducting qualitative research |

| J.N.B. | Male physician-scientist with a medical degree, extensive clinical and research expertise related to difficult communication in oncology, and clinical training and practice in pediatric hematology-oncology and hospice and palliative medicine |

| J.W.M. | Female physician-scientist with a medical degree, a master’s degree in public health, extensive research expertise in communication science, clinical training in pediatric hematology-oncology and hospice and palliative medicine, and practice in pediatric hematology-oncology |

Table 2. Codes and Definitions Derived From Raw Dialogue Data.

| Code | Definition |

|---|---|

| Human connection | |

| Remembering | Oncologist recalls information, unprompted, that is personal or important to the patient’s or family’s life |

| Sharing | Oncologist contributes personal information about themselves or their life in an effort to find common ground with a patient or family, such as character, emotions, personal life, or work habits |

| Friendly conversation | Oncologist use of small talk that does not include symptom discussion, treatment plan, medical care, emotional support, etc; includes back-and-forth small talk between parent and oncologist |

| Affection | Any time the oncologist, parent, or patient expresses a sentiment or feeling of fondness toward each other |

| Empathy | |

| Standing in another’s shoes | Oncologist uses empathetic statements to respond to emotions; includes validation of emotions and sharing grief; may also include countertransference (ie, ability to imagine oneself in the patient’s or family’s position) |

| Naming | Naming the emotions displayed by the patient or family |

| Understanding | Acknowledging and appreciating the patient’s or family’s situation; validating emotions |

| Respecting | Offering praise whenever appropriate; oncologist provides statement of reassurance and encouragement to parent or patient |

| Supporting | Expressing concern and a willingness to help |

| Exploring | Giving the patient or family an opportunity to talk about whatever they are feeling or processing; exploring sources of conflict (eg, guilt, grief, culture, family, and trust in medical team); exploring values behind decisions; includes a probing question |

| Saying sorry | Oncologist uses the phrase “I am sorry” or synonymous sentiments |

| Presence | |

| Being in the moment | Oncologist makes direct comments that indicate they are available and fully in the moment with the patient or family; comments that indicate the oncologist is not rushed and is purposefully giving their time to the patient or family |

| Silence | Code for any uninterrupted pause, in response to an emotion, that is 5 s or longer in length; pause with intention to create space for processing |

| Partnering | |

| Nonabandonment | Statements that indicate oncologist will be there to share the entire life or clinical experience with the patient or parent; in it for the long run |

| Team mentality | Any time statements are used that align or join the oncologist, patient, and family in collaborative goals and decision-making; includes “we” statements, indicating oncologist and family are a team or unit |

| Accommodating | Discussion of logistics that anticipate needs or accommodate life events for the patient or family |

| Inclusivity | |

| Open door | Oncologist uses open-ended language that prompts discussion of patient’s or family’s hopes, wishes, opinions, or goals of care; may be in relation to treatment options, location of care, or end-of-life preferences (do not code actual goals of care content) |

| Affirming | Statements that validate patient or parent as important in decision-making and integral to the process |

| Connecting symptoms | Oncologist links patient’s symptoms or pain with scan results or disease progression to provide clarity or understandable medical information |

| Using analogy | Oncologist uses an analogy or a prop to provide clarity or understandable medical information |

| Showing images | Oncologist shows the patient or family the imaging findings (or will show in the near future) to provide clarity or make medical information more understandable |

| Humor | |

| Comedy | Oncologist use of comedic relief, attempt at humor, and joking during conversations |

| Ribbing | The use of playful teasing by the oncologist |

| Matching maturity level | Oncologist matches the tone, language, and maturity level of a patient to connect with them |

| Honesty | |

| Warning shot | Oncologist opens with a statement that gives patient or family a moment to emotionally prepare for hearing bad news |

| Transparency | Oncologist uses statements that attempt to transmit or highlight realistic prognostic assessment related to delivering good or bad prognosis; a linguistic choice that captures oncologist attempt to bond through transparency; includes language about being honest or “I worry” statements |

| Giving opinion | Oncologist uses statements of ownership, including “I think,” “I feel,” “I recommend,” or “I believe,” or synonyms, while discussing illness course, treatment plan, goals of care; statements that show ownership or personalize opinion while building alliance or partnership with patient or family; includes any time the oncologist uses the phrase “If it were me or my child…” |

| Summarizing | The oncologist uses a summary statement to reiterate results, treatment, or findings of scans |

Data Analysis

Coding processes were conducted within MAXQDA, a mixed-methods data analysis software system.25 Three analysts (E.C.K., S.R., and C.W.) pilot tested the codebook across a series of medical dialogue recordings to identify areas of variance. All analysts met to reconcile variances and achieve consensus, modifying the codebook as needed to improve dependability, confirmability, and credibility of independent codes.26 Following codebook finalization, independent coding was performed by 2 analysts (S.R. and C.W.), with weekly meetings to review any coding variances and third-party (E.C.K. and J.N.B.) adjudication to reach consensus. Consistency in code segmentation also was reviewed to ensure a standardized approach (E.C.K., S.R., and C.W.). Code frequency, temporal duration, and distribution across discussion subtype were calculated and reported as descriptive statistics. Codes with greater frequency and impactful content were examined more closely, with further inductive exploration, categorization, and synthesis of identified quotes to generate themes (E.C.K., M.E.L., J.N.B., and J.W.M.). Identified themes were then incorporated into a summary figure, with input from all authors and iterative revision, to ensure that themes were appropriately integrated.

Results

In total, 33 patient-parent dyads were enrolled and followed longitudinally. From this cohort, 17 patient-parent dyads, representing all 6 participating oncologists, experienced advancing disease during the study period. Most patients were female (11 [64.7%]) and White (15 [88.2%]) individuals; additional participant demographic variables are presented in Table 3. In total, 141 disease reevaluation conversations were audio recorded, comprising approximately 2400 minutes of recorded dialogue. A median of 7 medical discussions per patient (range, 1-19) were recorded. Most patients (14 [82.4%]) died during the study period; 3 remained alive at 24 months. No participants formally dropped out of the study, although 1 dyad received care at another institution prior to death. Data on patient-parent dyads who declined enrollment in the larger study have been published previously.20 In brief, 7 of 41 approached dyads (17%) did not enroll owing to hesitation or refusal by either the patient (n = 4) or parent (n = 4). Although these numbers are small, refusal rates did not appear to disproportionately exclude dyads based on race and ethnicity. Only 1 of the 7 dyads self-identified as Black (approximately 14%) and 1 as Hispanic (approximately 14%), which are roughly equivalent to the percentages of Black patients and Hispanic patients treated at the institution.

Table 3. Participating Patient, Parent, and Oncologist Characteristics.

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient | |

| No. | 17 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 11 (64.7) |

| Male | 6 (35.3) |

| Race | |

| White | 15 (88.2) |

| Black | 1 (5.9) |

| Multiracial | 1 (5.9) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic | 17 (100) |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |

| 0-2 | 2 (11.8) |

| 3-11 | 6 (35.3) |

| 12-18 | 7 (41.2) |

| ≥19 | 2 (11.8) |

| Parent | |

| No. | 17 |

| Gender/role | |

| Female/mother | 14 (82.4) |

| Male/father | 3 (17.6) |

| Pediatric oncologist | |

| No. | 6 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 3 (50) |

| Male | 3 (50) |

| Race | |

| White | 6 (100) |

| Black | 0 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 0 |

| Non-Hispanic | 6 (100) |

| Years in clinical practice | |

| 1-4 | 2 (33) |

| 5-9 | 2 (33) |

| 10-19 | 0 |

| ≥20 | 2 (33) |

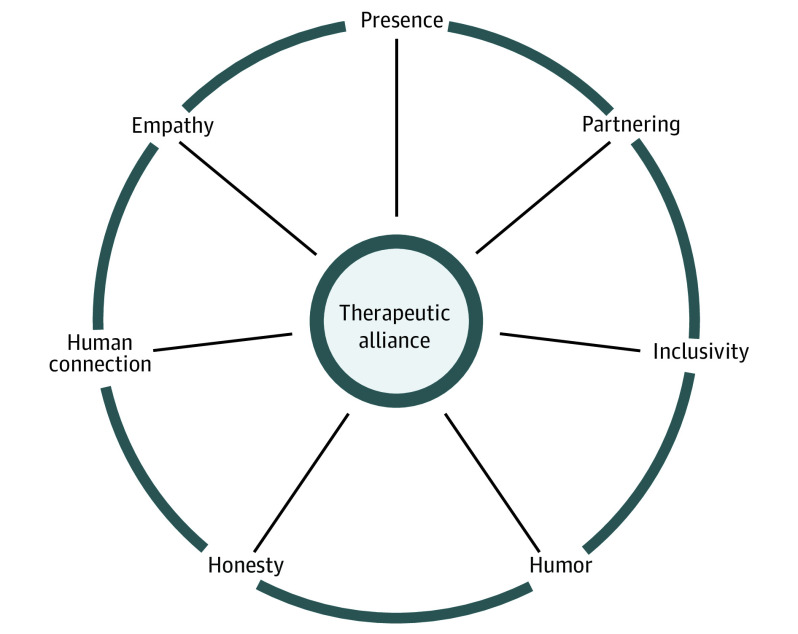

Across the advancing illness course, we identified 28 unique concepts as potential facilitators associated with therapeutic alliance, with further synthesis generating 7 core themes: human connection, empathy, presence, partnering, inclusivity, humor, and honesty (Table 4). We present these themes as a framework for potential facilitators associated with therapeutic alliance in pediatric cancer (Figure).

Table 4. Therapeutic Alliance Codes and Representative Quotes.

| Code | Example |

|---|---|

| Human connection | |

| Remembering |

|

| Sharing |

|

| Friendly conversation |

|

| Affection |

|

| Empathy | |

| Standing in another’s shoes |

|

| Naming |

|

| Understanding |

|

| Respecting |

|

| Supporting |

|

| Exploring |

|

| Saying sorry |

|

| Presence | |

| Being in the moment |

|

| Silence | NA |

| Partnering | |

| Nonabandonment |

|

| Team mentality |

|

| Accommodating |

|

| Inclusivity | |

| Open door |

|

| Affirming |

|

| Connecting symptoms |

|

| Using analogy |

|

| Showing images |

|

| Humor | |

| Comedy (making jokes) |

|

| Ribbing (gentle mocking) |

|

| Matching maturity level |

|

| Honesty | |

| Warning shot |

|

| Transparency |

|

| Giving opinion |

|

| Summarizing |

|

Abbreviations: NA, not available; PET, positron emission tomography.

Figure. Oncologist Approaches to Building Therapeutic Alliance in Pediatric Cancer.

Oncologists develop and deepen therapeutic alliance through 7 thematic approaches: human connection, empathy, presence, partnering, inclusivity, humor, and honesty. We present a framework for conceptualizing the interconnectivity and interdependency of these core facilitators associated with therapeutic alliance in pediatric cancer. The framework aesthetic intentionally resembles a wheel, evoking the idea that therapeutic alliance helps to move communication forward more productively, enabling clinicians, patients, and families to travel collaboratively across the illness course.

Human Connection

Oncologists promoted connection on a human level with the patient and family through 4 approaches. In the remembering approach, oncologists recalled information, unprompted, related to the patient’s or family’s personal life. Some recollections were lighthearted or fun (“Where is my birthday twin?”); other times, oncologists recalled prior feelings central to the patient’s values related to decision-making (“I know that in the past, you’ve also said it’s very hard to be away from family.”). Through sharing, oncologists also contributed personal information about themselves or their lives as an approach to find common ground with the patient or family. Shared information ranged from minor details about their personality or likes or dislikes (eg, “I’m not a reptile person.”) to a window into their personal life or emotions (eg, “I don’t know about you guys, but the uncertainty drives me crazy.”). Oncologists used friendly conversation or small talk unrelated to the illness or treatment plan to connect with patients and families. Finally, affection or expressions of fondness were also used to help generate connection on a human level: “It’s okay if you don’t want to, sweetheart.”

Empathy

We identified 7 facilitators of empathy, including 2 de novo concepts and 5 concepts originating from naming, understanding, respecting, supporting, and exploring, each of which was refined during the inductive coding process. In the first de novo concept, standing in another’s shoes, oncologists used empathetic statements to convey a willingness to imagine the patient’s or family’s struggle: “You guys are so wonderful. And I can only imagine how hard this is too because you’ve lost a lot of friends.” In the second de novo concept, saying sorry, oncologists used “I’m sorry” statements as a mechanism of conveying empathy: “I’m so sorry . . . that’s not what we wanted to talk to you about today.”

Oncologists also used naming to identify emotions that presented during discussion, such as fear, sadness, or anxiety. By labeling the reaction or feeling (eg, “You just got the most nervous look on your face” or “The tears are worries, I got it; it could be [disease]”), oncologists showed an ability to recognize the feelings of the patient or family. Oncologists also expressed understanding by acknowledging or appreciating the patient’s and family’s difficult situation and validating their emotions. At times, oncologists (or clinicians) repeated statements as a form of affirmation: [Patient: “That’s a lot of information.”] “It is a lot of information.” Oncologists showed respect through provision of encouragement, praise, or reassurance: “You did everything right.” Respect often overlapped with the concept of supporting, in which oncologists expressed concern alongside a willingness to help: “As long as you want to try something, we’re willing to try something.” Oncologists also cultivated empathy through the concept of exploring, in which they offered patients or family members an opportunity to talk about whatever they were feeling or processing: “What do you want to, what’s running through your head?”

Presence

We found 2 concepts that promoted a sense of meaningful presence as part of nurturing therapeutic alliance: being in the moment and silence. Oncologists verbalized with intention their willingness to stay in the moment, whether by giving time (eg, “We need to take the time. I think you guys deserve the time”) or by silencing other distractions (eg, “I turned my ringer off”). Silence was also used with intention to create space for processing and emotional connection.

Partnering

We discerned 3 concepts that fostered a sense of partnership among oncologists, patients, and their families. In the concept of nonabandonment, oncologists expressed a commitment to stay, no matter how difficult things became: “You know that you will never shake us, like good luck trying.” This concept of being “in it for the long run” also manifested through running imagery: “We love you, and we’re going, we’re all going to do this together, okay. This is a marathon and we’re all going to just keep running.” In the concept of team mentality, oncologists used “we” language to demonstrate a sense of teamwork and collaboration with respect to values, goals, or decision-making: “This is not a conversation that says that we don’t keep fighting because we always keep fighting.” Finally, in the concept of accommodation, oncologists partnered with patients and families by anticipating and meeting their needs and preferences. For example, the oncologists offered to reschedule visits or therapies to optimize quality of life: “I think we can do [the treatment] in a way that’s not going to interfere with the trips that you have planned.”

Inclusivity

We found 5 concepts that centered or included the patient or family with respect to transfer of knowledge or navigation of decision-making. In the open door concept, oncologists used open-ended statements to lay groundwork for sensitive conversations and to prompt patients or families to voice their hopes, wishes, opinions, or goals: “If that’s part of our goal . . . maybe we want to do that without getting into really intense things that are going to get you stuck in the hospital and things like that. You know, to me that seems like it would be a very, that would be a very reasonable goal, a good goal to have.” Oncologists also reinforced inclusivity by affirming the voice of the patient or parent as integral to decision-making: “Buddy, every decision that we make is the right decision for you because they’re your decisions, you know. We’re not, you know, whatever you decide is not ever going to be the wrong choice.”

Practically, oncologists used several concrete strategies to center the patient or family in medical dialogue. By connecting symptoms, they linked imaging findings with how a patient felt, translating abstract data into meaningful patient-centered information: “The biggest issues are in your bones. I think that’s why you feel bad.” By using analogies, oncologists simplified medical information into lay language for patients and families: “Your bone can look a little bit more like Swiss cheese, to use an analogy, and then the trouble with Swiss cheese is it has holes, and so if pushing on it having a lot of stress you can sometimes get a little bit of collapse.” Oncologists further included patients and families by showing imaging during discussions: “All this area over here is in her right shoulder, even though we radiated it, it’s much, much worse. All this super black stuff, that is disease.”

Humor

We identified 3 concepts related to humor as a key aspect of therapeutic alliance. In the concept of comedy, oncologists made jokes, often at their own expense, sharing in laughter with patients and families. Even serious conversations were sometimes punctuated by moments of levity or silliness via verbal or physical humor or sometimes through song. In the concept of ribbing, oncologists connected with patients or families through playful teasing: “She doesn’t have time for this. She’s got things to do. [Parent: Bother me for 1 of them.] Mm-hmm, bother, bother [patient]. That’s top, top of the list every day.” In the concept of matching maturity level, oncologists connected with patients by aligning their tone or language choices with the patient’s developmental stage: “I know that’s what you’re thinking, isn’t it? Yeah, like, loser, why haven’t we talked about this before?”

Honesty

We identified 4 concepts around honesty as a strategy to engender trust. In the warning shot concept, oncologists prefaced bad news with a forewarning to allow a patient or family to emotionally prepare: “So I’m afraid I don’t have very good news for you. So let me start from the beginning, okay.” In the concept of transparency, oncologists emphasized a desire to be honest or frank, particularly when discussing difficult information: “But it doesn’t mean that we don’t have plans. Okay, I just want to be honest.” Phrases such as “I worry” also enabled oncologists to share their thoughts candidly. Oncologists further fostered alliance via the giving opinions concept, using statements of ownership (eg, “I think,” “I feel,” “I recommend,” and “I believe”) when discussing illness progression, treatment planning, or goals of care: “I think we need to continue this therapy. Whether it’s really doing a lot or not, I don’t know, but I feel very uncomfortable stopping.” In the concept of summarizing, oncologists synthesized challenging information, thereby strengthening its trustworthiness: “What I would say, then, to kind of put the whole picture together, is that things are stable.”

Discussion

Therapeutic alliance is one core component of patient- and family-centered communication, particularly in the context of advancing illness. Through analysis of key conversations among pediatric oncologists, patients with advancing cancer, and their families, we identified 7 themes informing a framework for potential facilitators associated with therapeutic alliance: human connection, empathy, presence, partnering, inclusivity, humor, and honesty (Figure). This framework has possible utility in clinical practice and future research. When striving to create, sustain, or repair therapeutic alliance, particularly during stressful time points across an advancing illness course, clinicians might draw from this framework to emphasize certain facilitators with intention. Recognizing that personalities and communication styles naturally vary, clinicians may review the framework and choose to highlight behaviors that feel most genuine to them. We studied conversations recorded at times of crisis for patients and families, and even in these painful spaces, we found moments wherein clinicians created meaning (even laughter) through connection and caring. We hope that the facilitators underpinning this framework may help guide clinicians in forming meaningful therapeutic bonds, particularly when sharing difficult information, as a way to affirm our shared humanity and communicate to patients and families that their feelings matter.

This study also highlights the need for future investigation of several important, unexplored questions. We observed interactions among oncologists, patients, and their families across evolving illness, and we identified potential facilitators associated with therapeutic alliance. However, the identified concepts reflected our perspectives as clinicians and observers. We did not ask parents and children what they personally valued with respect to therapeutic alliance, and we do not know whether these interactions actually supported the human bond between clinicians and children or their families. We also do not know how cultural background or personal lived experiences may influence oncologists’ comfort levels with using certain facilitators of relationship building. For example, although the concept of “sharing personal information” emerged as a frequent approach, this method may not be appropriate or valued by everyone. Similarly, the act of “giving opinions” may come across as paternalistic by some stakeholders. The constructs that we identified, informing development of this initial theoretical framework, require validation to determine whether they align with what patients and families believe to be most important. Future investigation should consider participatory research methods to engage patients and families in assessing the trustworthiness of constructs and prioritizing communication approaches that they perceive to be most meaningful.

Although preliminary, this framework outlines key components associated with creating therapeutic alliance, filling a gap in the literature. Few existing conceptual frameworks characterize the variables intrinsic to development and evolution of therapeutic alliance in pediatric cancer care. One model derived from the experience of oncologists proposes a cyclical reinforcing association between effective communication and therapeutic alliance across the illness trajectory15; however, that model does not propose constructs for building alliance. Several models for therapeutic alliance in psychology and psychotherapy exist, yet their authors acknowledge ongoing challenges with application of the models toward measurement and characterization of therapeutic alliance in medicine.27,28

Several quantitative tools have been validated to measure therapeutic alliance between patients and oncologists. For example, The Human Connection scale is a psychometrically validated tool with Likert scale items that measures the extent of patient-reported mutual understanding, caring, and trust with their physicians, which has shown reliability in adult cancer populations.5 Yet given the nuance and complexity of therapeutic alliance, a mixed-methods approach that incorporates qualitative analysis has potential utility. Recognizing the potential role that therapeutic alliance plays in influencing patient care, caregiver well-being, and bereavement outcomes, studying therapeutic alliance as a potential modifiable factor is important. This theoretical framework offers potential infrastructure to further our understanding of therapeutic alliance in future cancer research.

Limitations

Study limitations include single-site design and potential sample bias for patient-parent dyads inclined to value or promote therapeutic alliance; all eligible oncologists participated, mitigating selection bias for physicians. Racial and ethnic diversity was limited and requires prioritization in future work. Rarely, discussions were not recorded due to logistical issues or at the request of the participating patient or parent; missing data might influence concept generation. However, given the saturation of themes across thousands of recorded minutes, several missing time points are less likely to influence the synthesis of findings.

Conclusions

Therapeutic alliance is an important aspect of the illness and care experience for children with cancer and their families. Drawing from longitudinal medical dialogue across an advancing illness course, we identified 7 core themes associated with therapeutic alliance: human connection, empathy, presence, partnering, inclusivity, humor, and honesty. These findings offer a framework to support clinician education and future opportunities to study key stakeholder perspectives on approaches to optimize therapeutic alliance among oncologists, patients, and their families.

References

- 1.Ruijs CDM, Kerkhof AJFM, van der Wal G, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. Symptoms, unbearability and the nature of suffering in terminal cancer patients dying at home: a prospective primary care study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Ullrich C, et al. Symptoms and distress in children with advanced cancer: prospective patient-reported outcomes from the PediQUEST Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1928-1935. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg AR, Orellana L, Ullrich C, et al. Quality of life in children with advanced cancer: a report from the PediQUEST Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(2):243-253. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siler S, Borneman T, Ferrell B. Pain and suffering. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019;35(3):310-314. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, et al. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: the Human Connection scale. Cancer. 2009;115(14):3302-3311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trevino KM, Maciejewski PK, Epstein AS, Prigerson HG. The lasting impact of the therapeutic alliance: patient-oncologist alliance as a predictor of caregiver bereavement adjustment. Cancer. 2015;121(19):3534-3542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An AW, Ladwig S, Epstein RM, Prigerson HG, Duberstein PR. The impact of the caregiver-oncologist relationship on caregiver experiences of end-of-life care and bereavement outcomes. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(9):4219-4225. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05185-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(3):438-450. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horvath AO, Symonds BD. Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol. 1991;38:139-149. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.38.2.139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stubbe DE. The therapeutic alliance: the fundamental element of psychotherapy. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2018;16(4):402-403. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20180022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dundon WD, Pettinati HM, Lynch KG, et al. The therapeutic alliance in medical-based interventions impacts outcome in treating alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95(3):230-236. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trevino KM, Abbott CH, Fisch MJ, Friedlander RJ, Duberstein PR, Prigerson HG. Patient-oncologist alliance as protection against suicidal ideation in young adults with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(15):2272-2281. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Cancer Institute. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering; NIH publication No. 07-6225. Published 2007. Accessed July 9, 2021. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/pcc_monograph.pdf

- 14.Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW. How parents of children with cancer learn about their children’s prognosis. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20172241. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blazin LJ, Cecchini C, Habashy C, Kaye EC, Baker JN. Communicating effectively in pediatric cancer care: translating evidence into practice. Children (Basel). 2018;5(3):40. doi: 10.3390/children5030040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mack JW, Kang TI. Care experiences that foster trust between parents and physicians of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(11):e28399. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaefer MR, Kenney AE, Himelhoch AC, et al. A quest for meaning: a qualitative exploration among children with advanced cancer and their parents. Psychooncology. 2021;30(4):546-553. doi: 10.1002/pon.5601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaye EC, Gattas M, Bluebond-Langner M, Baker JN. Longitudinal investigation of prognostic communication: feasibility and acceptability of studying serial disease reevaluation conversations in children with high-risk cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(1):131-139. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaye EC, Stall M, Woods C, et al. Prognostic communication between oncologists and parents of children with advanced cancer. Pediatrics. 2021;147(6):e2020044503. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-044503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(3):398-405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Tulsky JA, Fryer-Edwards K. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(3):164-177. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.3.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VitalTalk. Responding to emotion: respecting. Accessed January 24, 2021. http://vitaltalk.org/guides/responding-to-emotion-respecting/

- 25.Schönfelder W. CAQDAS and Qualitative Syllogism Logic-NVivo 8 and MAXQDA 10 compared. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2011;12:21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24(1):120-124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elvins R, Green J. The conceptualization and measurement of therapeutic alliance: an empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(7):1167-1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hougaard E. The therapeutic alliance—a conceptual analysis. Scand J Psychol. 1994;35(1):67-85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1994.tb00934.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]