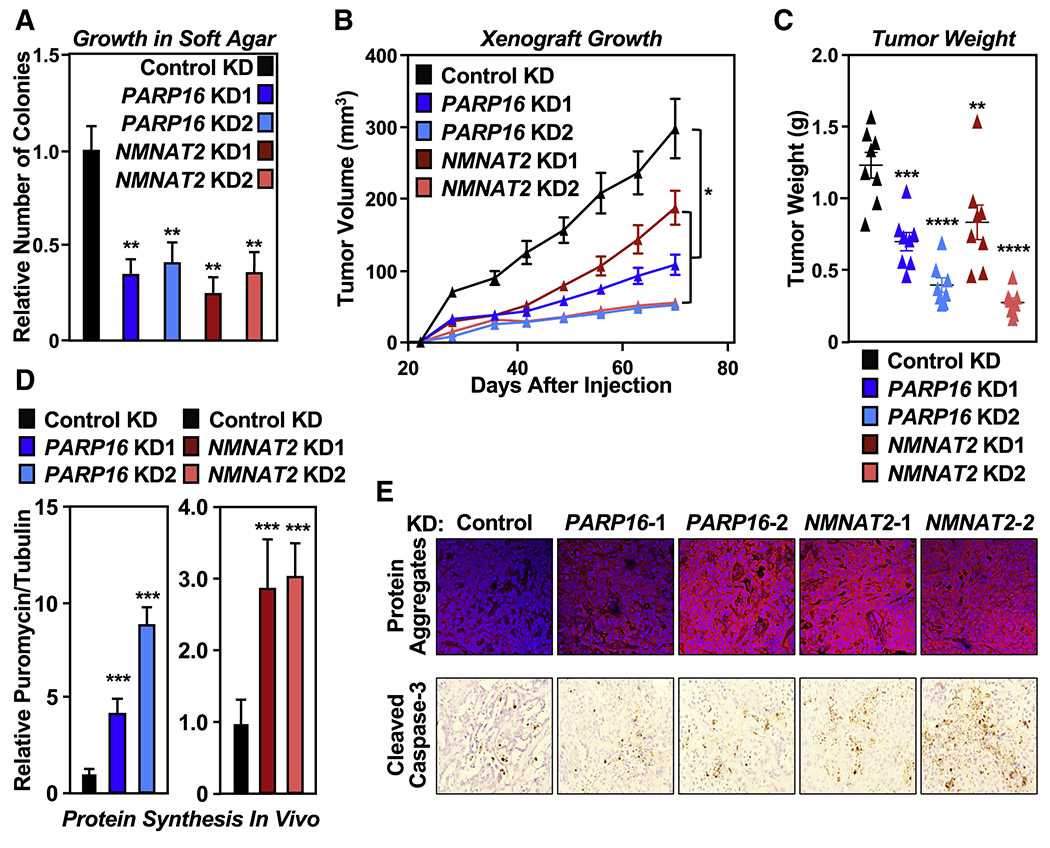

Figure 4. NMNAT-2 and PARP-16 support ovarian cancer cell growth through ribosomal protein MARylation.

(A) Depletion of PARP-16 or NMNAT-2 inhibits the anchorage-independent growth of OVCAR3 cells. Soft agar assay of OVCAR3 cells subjected to PARP16 or NMNAT2 knockdown. Each bar in the graph represents the mean ± SEM of the relative number of colonies (n = 3, one-way ANOVA, ** p < 0.01).

(B) Depletion of PARP-16 or NMNAT-2 inhibits the in vivo growth of xenograft tumors formed from OVCAR3 cells subjected to PARP16 or NMNAT2 knockdown (n = 8 per group, ANOVA, * p<0.05).

(C) Weights of tumors formed from OVCAR3 cells subjected to PARP16 or NMNAT2 knockdown (n = 8, one-way ANOVA, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.0001).

(D) Depletion of PARP-16 or NMNAT-2 enhances protein synthesis and protein aggregation in vivo. Each bar in the graph in (D) represents the mean ± SEM of the relative ratios of Western blot signals of puromycin to tubulin (n = 3, t-test with Holm-Sidak correction, *** p<0.001).

(E) Depletion of PARP-16 or NMNAT-2 causes proteotoxicity in vivo. Analysis of xenograft tumors described in (B) with Proteostat aggresome detection reagent staining and IHC using an antibody that recognizes cleaved caspase-3.

See also Figure S5.