Abstract

Background:

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) aims to cure Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) through reestablishing a healthy microbiome and restoring colonization resistance. Although often effective after one infusion, patients with continued microbiome disruptions may require multiple FMTs. In this N-of-1 study, we use a systems biology approach to evaluate CDI in a patient receiving chronic suppressive antibiotics with four failed FMTs over two years.

Methods:

Seven stool samples were obtained between 2016-18 while the patient underwent five FMTs. Stool samples were cultured for C. difficile and underwent microbial characterization and functional gene analysis using shotgun metagenomics. C. difficile isolates were characterized through ribotyping, whole genome sequencing, metabolic pathway analysis, and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determinations.

Results:

Growing ten strains from each sample, the index and first four recurrent cultures were single strain ribotype F078-126, the fifth was a mixed culture of ribotypes F002 and F054, and the final culture was ribotype F002. One single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variant was identified in the RNA polymerase (RNAP) β-subunit RpoB in the final isolated F078-126 strain when compared to previous F078-126 isolates. This SNV was associated with metabolic shifts but phenotypic differences in fidaxomicin MIC were not observed. Microbiome differences were observed over time during vancomycin therapy and after failed FMTs.

Conclusion.

This study highlights the importance of antimicrobial stewardship in patients receiving FMT. Continued antibiotics play a destructive role on a transplanted microbiome and applies selection pressure for resistance to the few antibiotics available to treat CDI.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, N-of-1 studies, microbiome, shotgun sequencing, metabolic analysis

Introduction

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is the most common cause of infectious diarrhea in the United States (US), affecting approximately 500,000 people annually.1,2 The pathophysiology of CDI involves disruption of the gut microbiome, most commonly through use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, which allows for the germination of C. difficile spores into vegetative, toxin-producing cells that cause disease.3 Symptoms of CDI range from diarrhea and abdominal pain to more serious complications such as ileus and pseudomembranous colitis.

Targeted antibiotic treatment with oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin is effective at killing C. difficile and resolving clinical symptoms.4 However, CDI recurrence occurs in 20-25% of patients given vancomycin once antibiotic treatment is discontinued.5 Fidaxomicin has a more narrow spectrum of activity and causes less dysbiosis over the course of treatment.6 Unlike vancomycin, fidaxomicin binds to C. difficile spores preventing outgrowth of vegetative cells.7 Accordingly, rates of recurrence following fidaxomicin use are approximately 50% lower than other treatments.8 Regardless of chosen therapy, the CDI recurrence rate increases with each subsequent episode of CDI, often requiring prolonged courses of antibiotics to control the disease. Although antibiotic resistance is increasing in C. difficile, the emergence of resistance during antibiotic therapy has rarely been reported.9

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) aims to cure CDI by restoring colonization resistance by reestablishing a healthy intestinal microbiome. Although one infusion is often effective, some patients may require two or more FMTs to resolve refractory CDI.10-13 Several risk factors for FMT failure have been identified including severe or severe-complicated CDI, inpatient status during FMT, and the presence of immunocompromising conditions.14 Continued use of non-CDI antibiotics, a risk factor for recurrent CDI in general, is also a risk factor for FMT failure.15,16

As part of an ongoing surveillance study to better understand the pathophysiology of CDI,17,18 we identified a patient with four FMT failures between 2016-18. Our biobank contained seven stool samples with accompanying clinical information from this patient over the two-year time period and provided us the unique opportunity to study the evolution of CDI over multiple FMTs. In this N-of-1 study, we use a systems biology approach to evaluate CDI in a patient receiving chronic suppressive antibiotics and who underwent four failed FMTs.

Methods

The subject was identified as part of an active surveillance system of patients with CDI approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Houston and participating hospitals.18 In this system, stool samples are collected from participating clinical microbiology laboratories and corresponding clinical information is collected from electronic medical records. The patient was identified during clinical data collection, after which our biobank was searched for previous samples from the same patient.

Microbiology and ribotyping:

Stool samples were selectively cultured on cycloserine-cefoxitin fructose agar (CCFA) at 37°C under anaerobic conditions for 48 hours for C. difficile growth.19 Isolates were confirmed to be C. difficile on the basis of growth on selective agar, morphology, and PCR confirmation for C. difficile toxin genes A and B and the C. difficile tpi gene. C. difficile isolates were then strain typed using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based ribotyping method.20 Ten isolates were taken from each culture to assess for the presence of mixed ribotypes.21 Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined for fidaxomicin, metronidazole, vancomycin, levofloxacin, eravacycline, and meropenem against isolated strains by broth microdilution in 0.1% sodium taurocholate Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) media as previously described.22

Genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction and whole genome sequencing:

gDNA was extracted from cryofrozen isolates and sequenced with both short- and long-read sequencing technologies as previously described.23 Briefly, C. difficile strains were incubated anaerobically on BHI agar for 48 hours. gDNA was extracted using the MasterPure Complete DNA & RNA Purification kit (Lucigen, MC85200), and used for both Illumina and Nanopore sequencing. Libraries of fragmented gDNA were prepared for Illumina sequencing using the NEXTflex Rapid DNA-Seq Kit (Bioo Scientific, NOVA-5149-02). Paired-end reads (2 x 150 bp) were generated on the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using the Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (MS-102-2002) and PhiX Control Kit v3 (FC-110-3001). Libraries of intact gDNA were prepared for Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing using ONT’s rapid barcoding kit (SQK-RBK004). Long-read sequencing was carried out on a MinION device with flow cell type R9.4.1 (FLO-MIN106D).

Sequence data processing and comparative analysis:

PhiX-filtered, paired-end Illumina reads were adapter trimmed and quality filtered with Trimmomatic v0.36 (Bolger 2014). Guppy v3.1.5 was used to basecall, quality filter (minimum qscore 10), demultiplex, barcode and quality trim ONT reads. Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) of Illumina reads was conducted using SRST2 (Inouye 2014) against the C. difficile MLST scheme.24 Nanopore and Illumina reads were combined for hybrid de novo assembly using Unicycler v0.4.8-beta in the conservative assembly mode and resulted in circular chromosomes. 25 Average genome coverages for short- and long-read sequences were calculated by BBMap v38.68 (https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/). Assemblies were annotated with NCBI Prokaryotic Annotation Pipeline.26 The genome of the index case (MHS-156) was closed and SNVPhyl was used to compared this to subsequent isolates using the core genome single nucleotide variant (cgSNV) method.27 Within-host diversity studies have defined the expected number of SNVs between epidemiologically identical isolates to be 0-2 SNVs for strains isolated within 124 days of each other.28

Carbon source utilization:

Carbon source utilization of isolated C. difficile strains was carried out using Biolog Phenotypic Microarray plates.29 Growth studies were conducted under anaerobic conditions (5% hydrogen, 90% nitrogen, 5% carbon dioxide) and strains were cultured overnight in BHI media supplemented with 0.5% w/v yeast extract. Overnight BHIS cultures (~16 hrs of growth) were diluted 1:10 in defined minimal media (DMM) lacking glucose.

Growth was monitored by optical density at 600 nm in a plate reader (Sunrise, Tecan). Growth was determined by comparison of growth in each carbon source to the negative control well lacking any carbon source.

Multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) screening:

Stool samples were screened for MDRO microbiologic colonization using standard microbiologic techniques.30 After stool growth on selective antibiotic media, antimicrobial resistance (genes) was determined by PCR including vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus spp. (vanA), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (mecA), carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae spp. (blakpc), and echinocandin-resistant Candida spp. (FKS1 and FKS2).31

16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing:

16S rRNA sequencing was performed to characterize microbial taxonomy. The V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was sequenced using an Illumina-based sequencing platform with a minimum of 15,000 reads per sample to assess the gut microbiome community structure.32 Quality filtered sequence reads with at least 97% similarity were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) and representative sequences from each OTU were assigned a taxonomic identity at the species level by searching against the NCBI 16S rRNA sequence database (release date September 1, 2018) using NCBI-BLAST+ package v2.8.1 2018. The microbial diversity indices were calculated using QIIME v1.9.0, where species richness and phylogenetic distance represented α-diversity, and Bray-Curtis and Weighted Unifrac were representative of β-diversity.33 R platform34 and GraphPad Prism 7.0 (San Diego, CA) were used for visualizing the results.

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing:

The DNA extracted from fecal samples previously used for 16S rRNA sequencing was shotgun metagenome sequenced using an Illumina-based platform for analysis of microbiome functional genes. The functional gene profiling of the shotgun metagenome was performed using HUMAnN2 v0.11.2 pipeline.35 In the preprocessing step, quality filtering of sequencing reads was performed and followed by screening and removal of contaminant host (human) reads. Trimmomatic v0.38 was used for the filtering and trimming of raw sequence data with the default cut-off settings. The reads were searched against a human genome database in paired-end mode using bowtie2 algorithm and were discarded if they were mapped to the database. To obtain the gene family profiles, these quality-controlled metagenome sequences were first searched against a nucleotide database (ChocoPhlAn) using bowtie2 and then against a protein database (UniRef90) using diamond. All the identified gene families were annotated using UniRef90 and pathways using MetaCyc identifiers. α- and β-diversities were generated with the gene family profiles.

Results

Patient case

The patient was a 42-year-old Caucasian female with a past medical history of systemic lupus erythematosus managed with hydroxychloroquine, chronic musculoskeletal pain syndrome, opioid dependence, autoimmune hepatitis treated with high dose steroids leading to avascular necrosis of multiple joints, hypothyroidism, type II diabetes mellitus, moderate obesity, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. As a result of her avascular necrosis, she underwent bilateral shoulder, bilateral hip, and bilateral knee replacements, after which she suffered from chronic prosthetic joint infections and osteomyelitis in her left knee leading to a left transfemoral amputation in 2013. In addition to these orthopedic procedures, her past surgical history is remarkable for thyroidectomy, appendectomy, and cholecystectomy.

Her antibiotic history prior included 12 courses of non-C. difficile antibiotics between early 2014 and her first CDI diagnosis in 2016. She completed antibiotic courses with glycopeptides, carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, tetracyclines, clindamycin, and linezolid. Between initial diagnosis (October 2016) and her fifth FMT (May 2018), she had 16 positive nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for C. difficile completed through either the BD Max Cdiff™ assay (BD Diagnostics, Becton, Dickinson and Company, NJ, USA) and/or the FilmArray® Gastroinestinal Panel (BioFire Diagnostics, Salt Lake City, UT). Choice of test was dictated by the preferred diagnostic at the hospital during the time period. Testing was at the discretion of the treating medical team based on suspected signs and symptoms of CDI Six of those 16 positive samples were available in our biobank and included in our analysis.

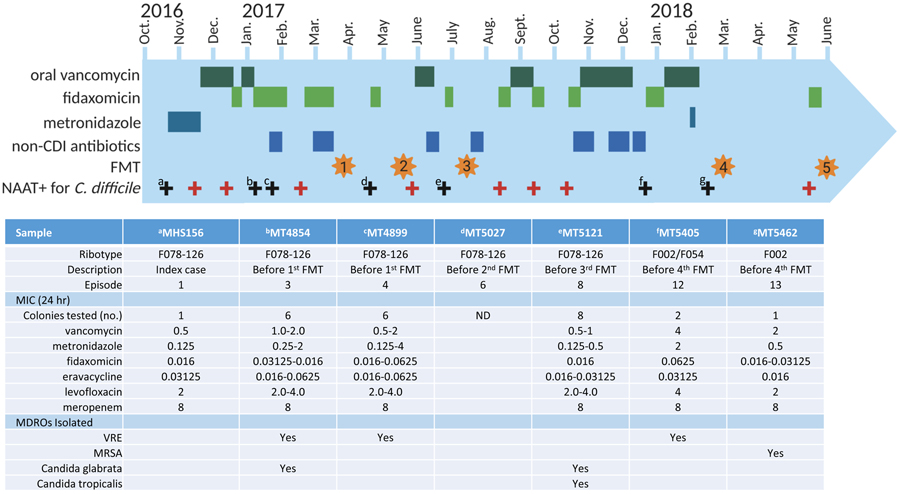

The stool instilled during each FMT was from a third-party donor (OpenBiome) and a volume of 250-350 mL of emulsified stool was instilled via colonoscopy each time. The patient received bowel preparation before the procedures, and loperamide 4 mg tablets two to four times daily following the procedure. Recurrent CDI after FMTs was treated with fidaxomicin, oral vancomycin, or fidaxomicin-vancomycin combination. Details of her clinical course including treatment are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline including treatment course, ribotypes, MIC determination, and presence of MDROs

Microbiology and ribotyping

The index C. difficile culture and six recurrent cultures were available for microbiologic analysis. Ribotyping indicated that the index C. difficile isolate and isolates from the first four recurrent episodes were single strain ribotype F078-126, representing true recurrent cases. C. difficile isolated from the fifth recurrent stool specimen constituted a mixture of ribotypes F002 and F054, while isolates from the final recurrent episode were ribotype F002, suggesting the final two episodes of CDI were new infections. Ribotyped, single pure isolates from each stool specimen are listed in Figure 1 and were characterized further for minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of vancomycin, metronidazole, fidaxomicin, eravacycline, levofloxacin, and meropenem. MIC determinations of these antibiotics were generally lower in the F078-126 isolates than the F002/F054 isolates and did not change appreciatively from the index to recurrent cases. Meropenem MICs were consistently 8 ug/mL for all strains and levofloxacin MICs were 2-4 ug/mL. Other MDROs identified in the stool samples included vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis (VRE), methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and two species of Candida. Details of ribotyping, MIC determinations, and MDRO colonization are shown in Figure 1.

Whole genome sequencing and SNP analysis

The C. difficile isolates from the first four recurrent episodes identified as the same ribotype (F078-126) as the index case (day 0) and were isolated 77, 96, 183, and 247 days from the index case. Hybrid de novo assembly of Illumina/Nanopore sequence data produced a complete circular sequence of the chromosome for the index C. difficile isolate MHS-156 which was used as a reference genome for downstream comparisons. Using SNVPhyl, the core genomes of MHS-156, MT4854, MT4899, and MT5027 were identical with zero SNVs present. However, a single cgSNV differentiated the index case from the genome of isolate MT5121 obtained from the fourth recurrent episode at 247 days post index. The SNV occurred at MHS-156 bp position 100,546 within the RNA polymerase β subunit (rpoB) gene. The cytosine at rpoB nucleotide position 1649 in isolate MT5121 had changed to adenine (C1649A), substituting serine with tyrosine at amino acid position 550 (S550Y).

Carbon source utilization

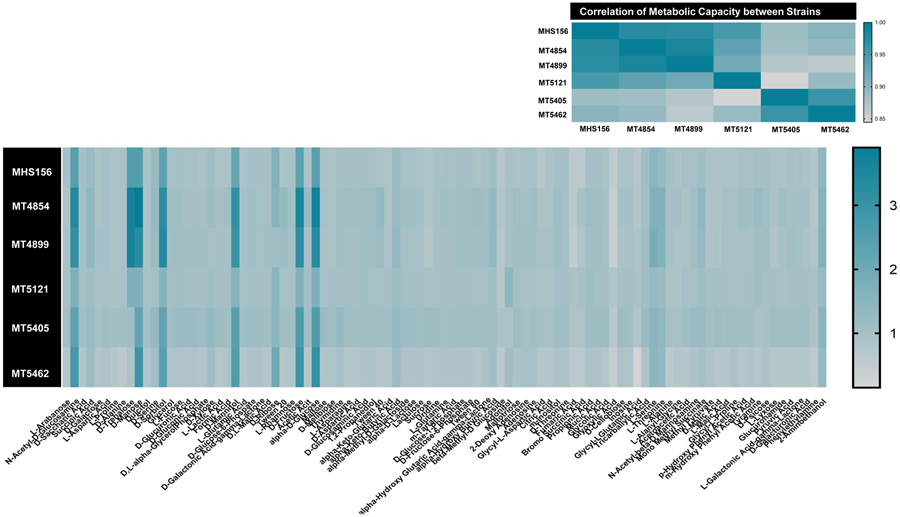

The Biolog growth assays were performed on the index strain and five strains isolated during recurrent infections including the final strain with the RpoB S550Y mutation. Overall, the growth of the strains aligns with what has been previously discovered with RT078 strains in that they can metabolize trehalose more efficiently than the F002 strains (bottom two strains, Figure 2). Other carbon sources tested did not show appreciable differences other than the fact that the strain MT5121 carrying the RpoB S550Y substitution grew more poorly than all of the other strains on carbon sources that supported significant growth (with the exception of the sugar alcohol adonitol).

Figure 2.

Metabolic capacity of C. difficile strains

MDRO colonization

Prior to her first FMT, the patient was colonized with VRE and C. glabrata. Colonization was not observed following her first FMT but C. glabrata and C. tropicalis were again cultured prior to her second FMT. Candida colonization was not observed after her second FMT but colonization with VRE and MRSA was observed. Details of MDRO colonization is shown in Figure 1.

Microbiome diversity and functional gene analysis

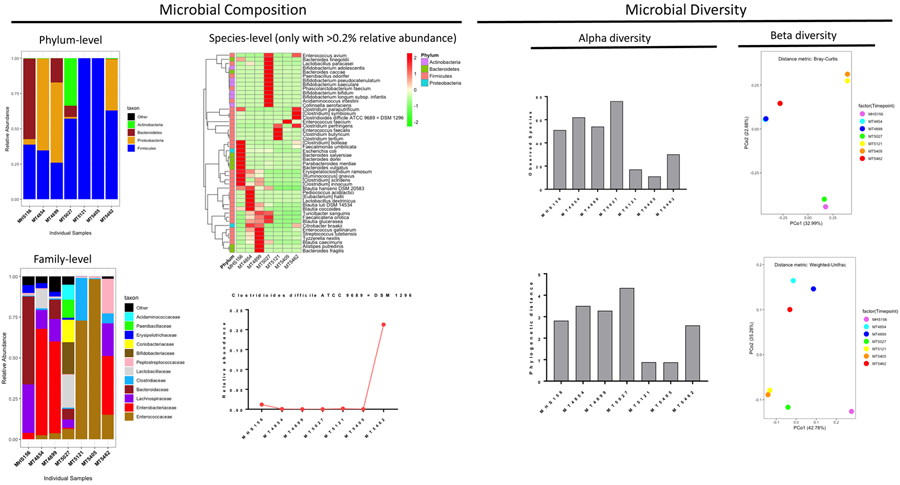

Marked differences at the phylum, family, and species levels were observed during the time course of the infection (Figure 3). During the index CDI case (MHS156), the majority of sequences were classified as Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. Proteobacteria, predominantly Enterobacteriaceae, were dominant in the second (MT4854) and third (MT4899) samples. Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and a larger diversity of organisms was observed for the fourth sample (MT5027), which was collected after her first FMT and in the absence of further antimicrobials. Firmicutes became dominant after another course of systemic, non-CDI antibiotics (MT5121) with eventual domination of Enterococcus faecium (MT5405) and Firmicutes with Proteobacteria (MT5462). C. difficile was low abundance during the entire course with the exception of her sixth (last) episode in which C. difficile accounted for approximately 20%.

Figure 3.

Microbial data analysis using 16S V3-V4 amplicon data

α-diversity decreased over time and especially during when the microbiome was dominated by few species (MT5121, MT5405, and MT5462). Changing β-diversity over time was also observed with the samples grouped roughly into three separate clusters (Figure 3).

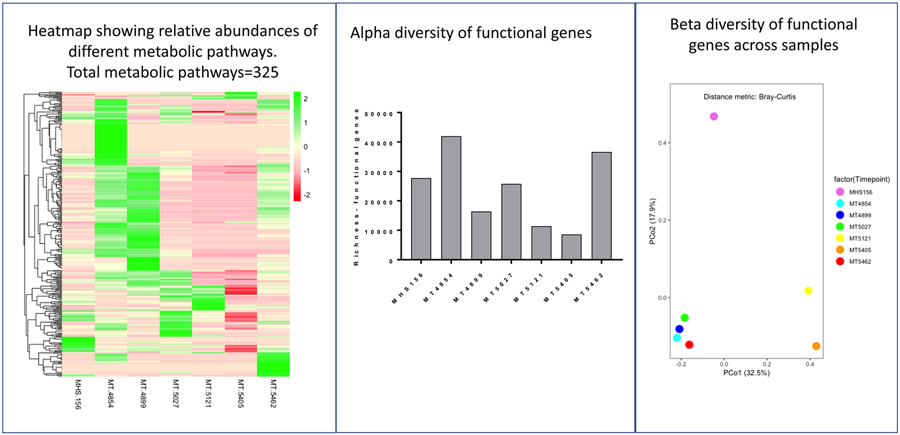

The functional gene analysis is shown in Figure 4. Overall relative abundance of different metabolic pathways (top 325) increased with MT4854 and MT4899 and changed markedly after the first FMT. Relative abundance of different metabolic pathways decreased as Firmicutes (MT5121) or E. faecium, specifically (MT5405), became dominant. Relative abundance of gene expression increased with increased α-diversity of microbiota (MT5462). The variation in microbiota composition (taxonomic composition) correlated with the functional gene composition (R2 = 0.877; p<0.01 by Mantel Haenszel Chi Square test).

Figure 4.

Functional gene analysis using shotgun metagenomics

Discussion

FMT can profoundly change the host microbiome and has changed the management of patients with recurrent CDI.10,36 Although remarkably effective at preventing CDI recurrence, many patients require more than one FMT due to a relapse of symptoms.37 As part of an ongoing study to better understand the systems biology of CDI, we identified a woman who failed several courses of FMT. She remained on suppressive antibiotic therapy for CDI for several years while concomitantly receiving other systemic antibiotics. This gave us a unique opportunity to explore a patient’s clinical course using state-of-the-art microbiome technologies.

Through the combined use of these technologies, we were able to provide multi-dimensional insight into our N-of-one case. Using PCR-fluorescent ribotyping, we demonstrated clinical infection was initially caused by one ribotype F078-126 infecting strain and was eventually replaced by another infecting strain (F002) after her third failed FMT. We sampled multiple colonies from each positive sample as previous studies had demonstrated that a mixed colony of ribotypes may predict CDI recurrence.21 Although we sampled ten strains per culture, it is possible we may have still had a mixed infection with one strain present at a low concentration. Although MICs to vancomycin or fidaxomicin did not change over the timeframe studied, whole genome sequencing revealed a single SNV at nucleic acid position 1649 in the MT5121 isolate that was associated with changing metabolic capacity. This could possibly indicate that the mutation in rpoB conferred a growth disadvantage over the other strains and may be the reason that although it may have provided an advantage over the previous F078-126 isolates in vivo in the presence of fidaxomicin that its poor growth set the stage for the F002 strains to cause later infections. This hypothesis will require future studies. We also demonstrated significant microbiome changes, including Proteobacteria overgrowth during continued therapy with oral vancomycin. Microbial diversity increased after FMT but decreased to almost complete Enterococcus spp. dominance with continued vancomycin therapy. Taken together, these experiments highlight several features that may contribute to the development of refractory CDI and to our patient’s multiple failed FMTs.

Concurrent antibiotic use is a well-recognized risk factor to predict failed FMT.37 In a multicenter study of 404 patients who underwent FMT for CDI, risk of recurrent CDI after FMT significantly increased in patients who also received systemic antibiotics (HR 8.4, 95% CI 4.2-16.9, p<0.001).34 Our study adds to these previous findings by demonstrating this disrupted microbiome includes overgrowth of Proteobacteria and Enterococcus dominance. In studies of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplants, these dysbiotic states were associated with increases in gram-negative bacteremia by 10-fold and VRE bacteremia by three-fold.38 Such studies contribute to the conclusion that a disrupted microbiome not only increases the risk for CDI and recurrent CDI development, but poor outcomes following infection as well.39

Chronic antibiotic use is also a driving force potentiating the development of antibiotic resistance, as seen in our case. We observed within-host microevolution in the last ribotype F078-126 isolate (MT5121) with a SNP identified at rpoB nucleotide position 1649. Previous studies demonstrated increased fidaxomicin MICs with SNP changes in the rpoB gene but generally at position 1143.40 No change in vancomycin and fidaxomicin MICs were observed in our patient, although changes in the metabolic profile were noted with this SNP change. Interesting, providers at the point of care commented in the medical chart on decreased clinical efficacy of fidaxomicin during this time period. The clinical significance of this microevolution while on antibiotic therapy will require further study.

In conclusion, our study highlights the importance of antimicrobial stewardship in patients receiving FMT. Continued use of antibiotics following FMT clearly disrupts the donor microbiome and hindered our patient’s ability to successfully engraft and restore colonization resistance. The emergence of micro-evolutionary changes within the genome of C. difficile underscores the reality of antibiotic selection pressure and the possible emergence of resistance to the few antibiotics available to treat this common infection. Future studies will be needed to offer better insight into how to continue to kill the infecting organisms while preserving or restoring a protective host microbiome.

Data availability.

The whole genome sequencing has been deposited under BioProject Number PRJNA732388 at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession JAHESB000000000. The version described in this paper is version JAHESB010000000. The annotated genomes are listed under the NCBI accession number CP075683, CP075684, and CP075685.

The pathophysiology of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) failures are not well understood

This patient level investigation used microbiologic and genomic techniques to investigate FMT failure

A single C difficile strain was noted for the majority of the entire study period

One single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variant was identified in the RNA polymerase (RNAP) β-subunit RpoB

This SNV was associated with metabolic shifts but phenotypic differences in fidaxomicin MIC were not observed.

Microbiome differences were observed over time during antibiotic therapy and after failed FMTs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) U01 AI124290-01 and R01 AI139261 and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists/BioMerieux Microbial Diagnostics in Antimicrobial Stewardship Research Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors state no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 2015;372(9):825–34. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guh AY, Mu Y, Winston LG, et al. Trends in U.S. Burden of Clostridioides difficile Infection and Outcomes. N Engl J Med 2020;382(14):1320–1330. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britton RA, Young VB Role of the intestinal microbiota in resistance to colonization by Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterology 2014;146(6):1547–53. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis 2018;66(7):987–994. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciy149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, et al. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59(3):345–54. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciu313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louie TJ, Cannon K, Byrne B, et al. Fidaxomicin preserves the intestinal microbiome during and after treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) and reduces both toxin reexpression and recurrence of CDI. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55Suppl 2:S132–42. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cis338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chilton CH, Crowther GS, Ashwin H, Longshaw CM, Wilcox MH Association of Fidaxomicin with C. difficile Spores: Effects of Persistence on Subsequent Spore Recovery, Outgrowth and Toxin Production. PLoS One 2016;11(8):e0161200. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crook DW, Walker AS, Kean Y, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection: meta-analysis of pivotal randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55Suppl 2:S93–103. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cis499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saha S, Kapoor S, Tariq R, et al. Increasing antibiotic resistance in Clostridioides difficile: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaerobe 2019;58:35–46. DOI: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.102072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 2013;368(5):407–15. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quraishi MN, Widlak M, Bhala N, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent and refractory Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46(5):479–493. DOI: 10.1111/apt.14201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullish BH, Quraishi MN, Segal JP, et al. The use of faecal microbiota transplant as treatment for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection and other potential indications: joint British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Healthcare Infection Society (HIS) guidelines. Gut 2018;67(11):1920–1941. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis 2018;66(7):e1–e48. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cix1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allegretti JR, Mehta SR, Kassam Z, et al. Risk Factors that Predict the Failure of Multiple Fecal Microbiota Transplantations for Clostridioides difficile Infection. Dig Dis Sci 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-020-06198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allegretti JR, Kao D, Sitko J, Fischer M, Kassam Z Early Antibiotic Use After Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Increases Risk of Treatment Failure. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66(1):134–135. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cix684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garey KW, Sethi S, Yadav Y, DuPont HL Meta-analysis to assess risk factors for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. J Hosp Infect 2008;70(4):298–304. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson TJ, Endres BT, Le Pham J, et al. Eosinopenia and Binary Toxin Increase Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With Clostridioides difficile Infection. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7(1):ofz552. DOI: 10.1093/ofid/ofz552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzales-Luna AJ, Carlson TJ, Dotson KM, et al. PCR ribotypes of Clostridioides difficile across Texas from 2011 to 2018 including emergence of ribotype 255. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020;9(1):341–347. DOI: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1721335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reveles KR, Dotson KM, Gonzales-Luna A, et al. Clostridioides (Formerly Clostridium) difficile Infection During Hospitalization Increases the Likelihood of Nonhome Patient Discharge. Clin Infect Dis 2019;68(11):1887–1893. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciy782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walk ST, Micic D, Jain R, et al. Clostridium difficile ribotype does not predict severe infection. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55(12):1661–8. (Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.) (In eng). DOI: 10.1093/cid/cis786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seekatz AM, Wolfrum E, DeWald CM, et al. Presence of multiple Clostridium difficile strains at primary infection is associated with development of recurrent disease. Anaerobe 2018;53:74–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basseres E, Endres BT, Khaleduzzaman M, et al. Impact on toxin production and cell morphology in Clostridium difficile by ridinilazole (SMT19969), a novel treatment for C. difficile infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71(5):1245–51. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkv498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spinler JK, Gonzales-Luna AJ, Raza S, et al. Complete Genome Sequence of Clostridioides difficile Ribotype 255 Strain Mta-79, Assembled Using Oxford Nanopore and Illumina Sequencing. Microbiol Resour Announc 2019;8(42). DOI: 10.1128/MRA.00935-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths D, Fawley W, Kachrimanidou M, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48(3):770–8. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01796-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 2017;13(6):e1005595. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Badretdin A, et al. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44(14):6614–24. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkw569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petkau A, Mabon P, Sieffert C, et al. SNVPhyl: a single nucleotide variant phylogenomics pipeline for microbial genomic epidemiology. Microb Genom 2017;3(6):e000116. DOI: 10.1099/mgen.0.000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eyre DW, Cule ML, Wilson DJ, et al. Diverse sources of C. difficile infection identified on whole-genome sequencing. N Engl J Med 2013;369(13):1195–205. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1216064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins J, Robinson C, Danhof H, et al. Dietary trehalose enhances virulence of epidemic Clostridium difficile. Nature 2018;553(7688):291–294. DOI: 10.1038/nature25178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halton K, Arora V, Singh V, Ghantoji SS, Shah DN, Garey KW Bacterial colonization on writing pens touched by healthcare professionals and hospitalized patients with and without cleaning the pen with alcohol-based hand sanitizing agent. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011;17(6):868–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beyda ND, John J, Kilic A, Alam MJ, Lasco TM, Garey KW FKS mutant Candida glabrata: risk factors and outcomes in patients with candidemia. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59(6):819–25. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciu407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fadrosh DW, Ma B, Gajer P, et al. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome 2014;2(1):6. DOI: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 2010;7(5):335–6. DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.R Core Team (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franzosa EA, McIver LJ, Rahnavard G, et al. Species-level functional profiling of metagenomes and metatranscriptomes. Nat Methods 2018;15(11):962–968. DOI: 10.1038/s41592-018-0176-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khoruts A, Dicksved J, Jansson JK, Sadowsky MJ Changes in the composition of the human fecal microbiome after bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010;44(5):354–60. DOI: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c87e02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allegretti JR, Kao D, Phelps E, et al. Risk of Clostridium difficile Infection with Systemic Antimicrobial Therapy Following Successful Fecal Microbiota Transplant: Should We Recommend Anti-Clostridium difficile Antibiotic Prophylaxis? Dig Dis Sci 2019;64(6):1668–1671. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-018-5450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taur Y, Xavier JB, Lipuma L, et al. Intestinal domination and the risk of bacteremia in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55(7):905–14. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cis580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peled JU, Gomes ALC, Devlin SM, et al. Microbiota as Predictor of Mortality in Allogeneic Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med 2020;382(9):822–834. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwanbeck J, Riedel T, Laukien F, et al. Characterization of a clinical Clostridioides difficile isolate with markedly reduced fidaxomicin susceptibility and a V1143D mutation in rpoB. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019;74(1):6–10. DOI: 10.1093/jac/dky375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The whole genome sequencing has been deposited under BioProject Number PRJNA732388 at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession JAHESB000000000. The version described in this paper is version JAHESB010000000. The annotated genomes are listed under the NCBI accession number CP075683, CP075684, and CP075685.