Abstract

It is well established that deictic gestures, especially pointing, play an important role in children’s language development. However, recent evidence suggests that other types of deictic gestures, specifically show and give gestures, emerge before pointing and are associated with later pointing. In the present study, we examined the development of show, give, and point gestures in a sample of 47 infants followed longitudinally from 10 to 16 months of age and asked whether there are certain ages during which different gestures are more or less predictive of language skills at 18 months. We also explored whether parents’ responses varied as a function of child gesture types. Child gestures and parent responses were reliably coded from videotaped sessions of parent-child interactions. Language skills were measured at 18 months using standardized (Mullen Scales of Early Learning) and parent report (MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory) measures. We found that at 10 months, show+give gestures were a better predictor of 18-month language skills than pointing gestures were, yet at 14 months, pointing gestures were a better predictor of 18-month language skills than show+give gestures. By 16 months, children’s use of speech in the interaction, not gesture, best predicted 18-month language skills. Parents responded to a higher proportion of shows+gives than to points at 10 months. These results demonstrate that different types of deictic gestures provide a window into language development at different points across infancy.

Keywords: show gestures, give gestures, point gestures, parent responsiveness, language development, infancy

Early language skills predict children’s long-term social and educational outcomes (Durand et al., 2013; Pace et al., 2019). Finding reliable early precursors of language can help us identify children at risk for language delays and inform interventions that promote optimal development. One important predictor of language outcomes identified in the literature is children’s gesture use. Iverson and Goldin-Meadow (2005) reported that the lexical items in a child’s spoken vocabulary could be predicted by looking at which objects the child referenced using gestures, approximately three months earlier. Rowe, Özçalişkan, and Goldin-Meadow (2008) found that children’s gesture use at 14 months predicted vocabulary size at 42 months, controlling for spoken vocabulary at 14 months, suggesting that at the early stages of language development, gesture may be a more sensitive indicator of later language skill than speech.

Deictic gestures, in particular, have been well researched regarding their role in language development. Deictic gestures indicate objects, people, and locations in the environment and include show, give1, and point gestures (Capone & McGregor, 2004). Further, deictic gestures, by definition, depend on the immediate context, so their referents are clear and are likely to elicit contingent input from adults (Goldin-Meadow, 2007; Özçalışkan et al., 2016). For example, when a child shows or points at a ball, the caregiver might say, “it’s a ball”, providing a direct label for the child’s gesture referent. In contrast, conventional gestures (which are culturally defined; e.g., nodding head for yes) or representational gestures (which are metaphoric; e.g., flapping arms to indicate flying), can be more arbitrary in forms and can have less a direct connection between a symbol and its referent, thereby possibly playing a lesser role in children’s language learning relative to deictic gestures.

Accordingly, many researchers seeking to identify predictors of language have focused their attention on early use of deictic gestures, especially on pointing. A meta-analysis of 25 research studies on pointing and language development reported that there were robust associations between the two domains and that these associations became stronger during the second year of life (Colonnesi et al., 2010). Numerous gesture studies in typical development have noted pointing as a hallmark gesture and refer to it as the “most powerful of the deictic gestures” (Aureli et al., 2017, p. 802) and “most important for predicting word onset” (McGillion et al., 2017, p. 157). Similarly, pointing has been the most frequently studied gesture in autism research (Manwaring et al., 2018).

While pointing has been closely examined in the literature, there has been relatively less research on other types of deictic gestures, such as show and give gestures (Boundy et al., 2016; Cameron-Faulkner et al., 2015; Moreno-Núøez et al., 2020). However, recent evidence suggests that show and give gestures may be more important communicative milestones than previously recognized. Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2015) found that show and give gestures emerged around 10 months, prior to points, and were positively associated with use of points at 12 months (which typically have declarative or sharing intentions), but not with production of reaches (which generally are associated with imperative or requesting intentions). Moreno-Núøez et al. (2020) reported that children produced show and give gestures towards an intentional communicative goal much more frequently than point gestures from 9 to 13 months. Together, these findings suggest that show and give gestures precede and predict pointing gestures and may represent children’s intentional communication in infancy.

Despite the emerging evidence suggesting the important role of show and give gestures in early communicative interactions, the development of these gestures has rarely been followed longitudinally in the same children (Bates et al., 1975; Carpenter et al., 1998; Moreno-Núøez et al., 2020). Considering that show and give gestures are associated with later points (e.g., Cameron-Faulkner et al., 2015) and that points predict later language (e.g., Colonnesi et al., 2010), it is plausible that show and give gestures may predict subsequent language outcomes and that they may do so earlier than pointing gestures. Yet, limited research has examined the role of show and give gestures in language development (Bates, Benigni, Bretherton, Camaioni, & Volterra, 1979; Donnellan, Bannard, McGillion, Slocombe, & Matthews, 2020). Furthermore, it remains unknown whether parents respond to a higher proportion of one gesture type (e.g., shows), compared to other gesture types (e.g., points). As some research suggests that parental responses vary as a function of child gestural and vocal communication types (Leezenbaum et al., 2014; Talbott et al., 2016), it is possible that parent responsiveness may differ to each of the gesture type and may also serve as a mechanism in explaining relations between different gesture types and language development in children.

The goal of the present study is to investigate the emergence of shows, gives, and points in a sample of infants followed longitudinally from 10 to 16 months of age and to determine whether and when these gestures best predict subsequent language skills at 18 months. Additionally, we explored whether parent responses differed as a function of child gesture type. The specific research questions are as follows: (1) Does the variation in children’s production of show, give, and point gestures between 10 and 16 months predict language production and comprehension at 18 months? (2) Are parents more likely to respond contingently to one gesture type (e.g., shows) versus another gesture type (e.g., points)?

Methods

Participants

Data were drawn from a gesture intervention study, which intended to increase use of pointing in parents and their children from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds (Rowe & Leech, 2019). Parent-child dyads were recruited using direct mailings as well as advertisements in social media and community in a large metropolitan area in the Northeast US. Fifty families were enrolled in the study. Among these 50 families, two dyads were excluded because they did not participate in visits after baseline, and another family was excluded because the parent participating in the parent-child interaction (described below) changed during the study. Thus, our final sample comprised of 47 families (46 mothers, 1 grandmother). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. All children had a minimum gestational age of 37 weeks, had no known developmental diagnosis, and were from primarily English-speaking households (i.e., English spoken at least 75% of the time).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 47)

| Demographic Variable | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Parent Education Levela | |

| 8th grade or less | 0 |

| Some high school | 1 |

| GED | 1 |

| High school diploma | 1 |

| Some college | 13 |

| 2 year or professional degree | 5 |

| 4 year college degree | 9 |

| Advanced degree | 17 |

| Household Income Levelb | |

| < $15,000 | 5 |

| $15,000-30,000 | 7 |

| $30,000-45,000 | 3 |

| $45,000-60,000 | 0 |

| $60,000-75000 | 2 |

| $75,000-90,000 | 6 |

| > $ 90,000 | 23 |

| Child Sex | |

| Male | 22 |

| Female | 25 |

| Child Race | |

| American Indian | 0 |

| Asian | 0 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 |

| Black or African-American | 4 |

| White | 34 |

| More than One Race | 8 |

| Other | 1 |

| Birth Order | |

| First born | 26 |

| Later born | 21 |

Parent education was reported as the highest level attained on a eight-point scale (i.e., 1 = 8th grade or less; 8 = advanced degree). Using this categorical information, we created a continuous variable to calculate years of parent education for our analyses to examine relations between early gesture and language development. We coded 10 years if the parent did not graduate high school, 12 if the parent obtained a high school diploma or GED, 14 if the parent had some college (but no degree) or two-year or professional degree, 16 if the parent had a four-year college degree, and 18 if the parent obtained an advanced degree.

One family did not report the income.

Procedures and Measures

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the Harvard University (IRB14-2973, A Gesture Training for Low-income Parents to Improve Child Language Development). Written, informed consent was obtained from all parents prior to their children’s participation in the study. Data were collected at families’ homes at child age 10, 12, 14, 16, and 18 months.

Gesture Intervention.

At 10 months (i.e., baseline), families were randomized into a control or intervention group after demographic information and videotaped parent-child interactions were collected. Parents in the intervention group were then shown a 5-minute training video focused on increasing use of gestures, particularly pointing, with children. The video emphasized the importance of gestures in promoting child development and showed examples of parent-child dyads using gestures during play (e.g., how parents can point with children and respond to children’s gestures). Parents in the control group did not receive the training video.

Gesture Measures.

At 10, 12, 14, and 16 months, parent-child dyads engaged in 15-minute semi-structured play interactions at home. Parents were asked to play with their child as they normally would and were provided with three bags of age appropriate toys (e.g., book, shape sorter, farm set). Of note, a play situation was chosen, as the study was advertised as a project about play and child development. Further, the three-bag task is a commonly used situation to investigate early parent-child communicative behaviors (e.g., Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015; Vandell, 1979), and we chose toys that we thought would specifically elicit gestures. These parent-child interactions were videotaped and later transcribed by trained research assistants using the CHAT (Codes for Human Analysis Transcripts) transcription conventions of the Child Language Data Exchange System (MacWhinney, 2000). Specifically, trained research assistants, who achieved 95% agreement on utterance boundaries of the parent-child interactions with an experienced transcriber, reliably transcribed each session at the utterance level and identified occurrences of gestures by watching the videotaped session of the interaction. Each transcript was then verified by a second coder to ensure that all speech was accurate and a separate second coder to check that all gestures were captured accurately. Gesture coding was then done by a separate set of three coders and reliability was conducted on a subset of the videotaped sessions with percent agreement of 88% and a mean Cohen’s kappa of .86.

The present study focused a priori on the following types of deictic gestures: show (holding up an object in a communicative partner’s sight; i.e., “look at this!”), give (holding up an object for a partner to take; i.e., “I want you to take this!”), and point (extending the index finger toward a referent). Whole-hand points were not included. All show, give, and point gestures were counted whether or not they occurred with eye gaze or during joint attention. Of note, there is a substantial heterogeneity in the definition of show and give gestures across studies (Supplemental Information, Table S1; see Colonessi et al. 2020 for discussion of the varying definitions of pointing gestures). While our definitions of show and give gestures were comparable to those of earlier work (e.g., Cameron-Faulkner et al., 2015), micro-behaviors found to differentiate show and give gestures such as an arm position and hand orientation (Boundy et al., 2016) were not considered in coding, as they were not of interest for the current study, and the shows and gives were combined later in the analyses.

Parent Responses.

Parent responses were coded if they occurred within the first two utterances following the child’s show, give, or, point gesture, and they were categorized as contingent or non-contingent. We determined that the response was contingent if the parent provided a verbal or nonverbal input related to the child’s gesture. For example, when the child pointed at a car and the parent responded, “You found a car!” or showed the car to the child, the response was coded as contingent because the parent responded to their child’s referent. By contrast, when the parent redirected the child’s attention or did not respond, the response was coded as non-contingent. For example, when the infant pointed at a car and the parent said, “Do you want to read a book?” the response was coded as non-contingent because the parent did not respond to their child’s referent. Reliability between two coders was assessed on 13% of the transcripts, with percent agreement of 89% and Cohen’s kappa of .72.

Language Skills.

At 18 months, children’s language skills were measured using the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen; Mullen, 1995) and the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (CDI; Fenson et al., 1994). The Mullen is an experimenter-administered, standardized assessment with five subscales (Expressive Language, Receptive Language, Fine Motor, Gross Motor, and Visual Reception), which provide an overall index of cognitive functioning in children from birth to 68 months. In the original study (Rowe & Leech, 2019), only the Expressive Language subscale of the Mullen was administered. Standardized (T) scores from the Mullen Expressive Language subscale were used to assess children’s language skills in the present study. The CDI is a parent report measure for assessing communicative and language development in young children. We used the CDI short-form version, which contains a 89-word checklist for vocabulary production and comprehension for 8- to 18-month-olds (Fenson et al., 1994).

Covariates.

Given that previous research has found that parent education, sex, birth order, and early vocabulary relate to language development (Hoff, 2003; Huttenlocher et al., 1991, 2010; Rowe et al., 2008), we considered these variables as potential covariates in data analyses. To control for child vocabulary at 10 and 12 months when children were producing very little language, we used vocabulary comprehension scores from the CDI. At 14 and 16 months when there was substantial variation in child speech at these ages (Table 2), child number of different words, derived from parent-child interactions, served as a measure of vocabulary. In addition, we consider intervention status (0 = control, 1 = intervention) as a potential covariate given the intervention design of the study.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations among Gestures, Language Skills, and Covariates

| Mean | SD | Range | Correlations with 18-month Mullen |

Correlations with 18-month CDI Production |

Correlations with 18-month CDI Comprehension |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shows+Gives | ||||||

| 10 Months | 0.83 | 1.51 | 0-6 | 0.39* | 0.41** | 0.10 |

| 12 Months | 2.87 | 3.24 | 0-12 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.14 |

| 14 Months | 3.70 | 4.95 | 0-19 | 0.15 | −0.05 | −0.14 |

| 16 Months | 6.12 | 7.83 | 0-41 | −0.03 | −0.17 | −0.19 |

| Points | ||||||

| 10 Months | 1.38 | 3.78 | 0-22 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| 12 Months | 2.36 | 3.36 | 0-13 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.09 |

| 14 Months | 8.56 | 12.12 | 0-62 | 0.48** | 0.43** | 0.35* |

| 16 Months | 8.43 | 9.44 | 0-42 | 0.49** | 0.48** | 0.34* |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Parent Education | 15.53 | 2.14 | 10-18 | 0.32* | −0.04 | −0.19 |

| Child Vocabularya | ||||||

| 10 Months | 8.93 | 7.91 | 0-34 | 0.05 | 0.33* | 0.57*** |

| 12 Months | 21.21 | 12.74 | 2-48 | 0.14 | 0.39* | 0.52*** |

| 14 Months | 3.00 | 3.39 | 0-13 | 0.42** | 0.47** | 0.40* |

| 16 Months | 8.95 | 8.85 | 0-28 | 0.80*** | 0.77*** | 0.49** |

| Child Sex | - | - | - | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.22 |

| Child Birth Order | - | - | - | −0.21 | −0.11 | −0.01 |

| Intervention Group | - | - | - | −0.02 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

Note.

Child vocabulary was measured using the CDI comprehension scores at 10 and 12 months because children mostly vocalize and do not produce words at these ages. At 14 and 16 months, child vocabulary was measured using speech (word types) derived from the interactions.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Results

Preliminary Analyses: Gesture Absence Versus Gesture Presence

Because show and give gestures were produced at relatively low frequency (Table 2) and both represent proximal communicative behaviors, they were combined into one category (hereafter, “shows+gives”), similar to the approach used in Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2015). Figure 1 shows the percentages of children who produced shows+gives and points at 10, 12, 14, and 16 months. Given that some children did not produce these gestures, we first examined the presence or absence of the gesture types in relation to later language measured on Mullen and CDI. In other words, children were classified as those who produced shows+gives or those who did not produce shows+gives, as well as those who displayed points or those who did not display points at each age; then, their mean language scores at 18 months were compared using independent samples t-tests (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Percentage of children who produced shows+gives (light gray) and points (dark gray) between 10 and 16 months of age (n = 47). Shows+gives were produced by 34%, 67%, 77%, 86% of children at 10, 12, 14, and 16 months, respectively. Points were produced by 34%, 51%, 86%, and 88% of children at 10, 12, 14, and 16 months, respectively.

Figure 2.

Comparison of mean language scores on (a) the Mullen Expressive Language subscale, (b) the CDI Productive Vocabulary, and (c) the CDI Receptive Vocabulary at 18 months between children who produced no shows+gives (light gray), children who produced shows+gives (light gray with pattern), children who produced no points (dark gray), and children who produced points (dark gray with pattern) at 10 and 14 months. Of note, language skills of children did not differ depending on whether or not the child produced shows+gives or points at 12 or 16 months.

At 10 months, children who produced shows+gives had significantly higher scores on 18-month language production measures, compared to their peers who did not produce any shows+gives, Mullen: t(39) = −2.45, p = .019; CDI production: t(38) = −2.14, p = .039. At 12 months, children who produced shows+gives or points did not differ in 18-month language scores from those who did not produce such gestures. At 14 months, children who pointed in the interaction had higher 18-month language production and comprehension scores than non-pointers, Mullen: t(37) = −2.62, p = .013; CDI production: t(36) = −3.08, p = .004; CDI comprehension: t(36) = −2.29, p = .028. At 16 months, children who produced shows+gives or points did not differ in 18-month language scores from those who did not produce such gestures. In sum, these preliminary analyses indicated that the presence of 10-month shows+gives or 14-month points was related to 18-month language scores.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Next, we examined the shows+gives and points as continuous measures to determine whether individual variability in shows+gives and points between 10 and 16 months related to language skills at 18 months. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between gesture variables at 10, 12, 14, and 16 months and language scores at 18 months are presented in Table 22. As shown in Table 2, individual variation in shows+gives at 10 months was related to language scores on the Mullen and CDI production at 18 months. However, by 12 months, this relation between shows+gives and later language was no longer evident. Shows+gives at 10 months also predicted later pointing (rs = .34-.40, p < .05), and variation in pointing at 14 and 16 months (not 10 or 12 months) was related to later language at 18 months.

Additionally, bivariate correlations between potential covariates and child language at 18 months were examined. We found that parent education and early child vocabulary were significantly associated with language outcomes. However, sex, birth order, and intervention group were not associated with 18-month language measures in our sample. Thus, sex, birth order, and intervention status were dropped from subsequent analyses and are not discussed further here. We continued examining the significant results of these correlational analyses with regression analyses to determine whether the effect of a specific gesture measure (i.e., 10-month shows+gives; 14-month points; 16-month points) on language holds, even when parent education and child vocabulary are controlled.

Do Show+Give and Point Gestures Across Infancy Differentially Predict Later Language?

To investigate the ages at which different types of deictic gestures best predict later language skills, we conducted a series of regression analyses first predicting the Mullen and then the CDI. Children’s scores on the Mullen and the CDI at 18 months were moderately correlated, Mullen and CDI production: r = .61, p < .001; Mullen and CDI comprehension: r = .43, p = .007, and we were interested in whether findings would be similar across the outcomes.

Regression Analyses Predicting Mullen Expressive Language.

Table 3 shows the results of regression models predicting children’s language scores measured on the Mullen Expressive Language subscale at 18 months. Model 1 shows that 10-month shows+gives predicted later Mullen scores, even with parent education and 10-month vocabulary controlled, b = 5.27, S.E. = 1.91, p = .009, β = 0.39. Model 2 displays that 14-month points predicted later Mullen scores while controlling for parent education and 14-month vocabulary, b = 1.87, S.E. = 0.87, p = .040, β = 0.32. Model 3 shows that 16-month points did not predict later Mullen scores, controlling for parent education and 16-month vocabulary. Instead, 16-month vocabulary (i.e., the number of different words children spoke during parent-child interactions) was a significant positive predictor, b = 0.98, S.E. = 0.16, p < .001, β = 0.70. Finally, in Model 4, when both 10-month shows+gives and 14-month points were entered in the same model simultaneously to determine their independent contributions to later language, both gesture types were significant predictors (p < .05) of later Mullen scores, with parent education controlled. Of note, 16-month points were not included in Model 4 because by 16 months speech best predicted language.

Table 3.

Regression Models Predicting Mullen Expressive Language Scores at 18 Months Using Different Types of Early Deictic Gestures

| Mullen Parameter Estimate (SE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Intercept | 11.37 (14.94) | 24.35~ (12.07) | 14.87 (10.07) | 28.86* (12.40) |

| Parent Education | 2.22* (0.87) | 1.22 (0.78) | 1 77** (0.64) | 1.02 (0.81) |

| Concurrent Vocabulary | 0.38 (0.21) | 1.17** (0.42) | 0 98*** (0.16) | |

| 10-month Shows+Gives | 5.28** (1.91) | 4.71* (1.95) | ||

| 14-month Points | 1.87* (0.87) | 2.03* (0.94) | ||

| 16-month Points | 0.04 (0.90) | |||

| N | 39 | 38 | 37 | 39 |

| R2 (%) | 29.8 | 38.5 | 66.0 | 33.0 |

Note. Because gesture variables were not normally distributed, violating the multivariate normality assumption of linear regressions, they were square root transformed. Concurrent vocabulary refers to children’s vocabulary measured at the same visit as their gestures (e.g., 10-month CDI vocabulary was used as a covariate in Model 1 to examine 10-month shows+gives as a predictor of later language).

p < .1

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Thus far, we found that children’s 10-month shows+gives, 14-month points, and 16-month speech each uniquely predicted later language scores measured on the Mullen, an experimenter-administered assessment. Next, we investigated whether the same relations would be found when using the CDI, a parent report measure. As the Mullen was an expressive language measure in the present study, we start with the CDI production and follow with CDI comprehension.

Regression Analyses Predicting CDI Production.

Table 4 shows the results of regression models predicting children’s CDI production scores at 18 months. We present our models in the same order as above. In Model 1, 10-month shows+gives were significantly positively associated with CDI production at 18 months, controlling for parent education and 10-month vocabulary, b = 9.58, S.E. = 3.78, p = .016, β = 0.38. Next, 14-month points were significantly positively associated with later CDI production when controlling for parent education, b = 4.39, S.E. = 1.89, p = .027, β = 0.39, but its effect was reduced to marginal significance upon the inclusion of 14-month vocabulary due to potential collinearity (Model 2), b = 3.88, S.E. = 2.04, p = .066, β = 0.34. In Model 3, controlling for parent education and 16-month vocabulary, 16-month points did not predict later CDI production; however, 16-month vocabulary did, b = 1.54, S.E. = 0.29, p < .001, β = 0.76. In Model 4, both 10-month shows+gives and 14-month points were, again, significant predictors of later CDI production, with parent education controlled. In sum, these results were highly consistent with the reported results for the Mullen. We next investigated whether these gestures also predicted the CDI comprehension at 18 months.

Table 4.

Regression Models Predicting CDI Production Scores at 18 Months Using Different Types of Early Deictic Gestures

| CDI Production Parameter Estimate (SE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Intercept | 9.84 (28.92) | 43.69 (27.99) | −13.42 (16.98) | 48.52~ (24.49) |

| Parent Education | 0.45 (1.70) | −1.68 (1.81) | 1.69 (1.10) | −2.12 (1.61) |

| Concurrent Vocabulary | 0.74 (0.43) | 0.71 (1.02) | 1 54*** (0.29) | |

| 10-month Shows+Gives | 9.58* (3.78) | 8.27* (3.88) | ||

| 14-month Points | 3.88~ (2.04) | 3.72* (1.83) | ||

| 16-month Points | −0.82 (1.61) | |||

| N | 39 | 38 | 37 | 38 |

| R2 (%) | 21.7 | 14.9 | 56.7 | 23.9 |

Note. Because gesture variables were not normally distributed, violating the multivariate normality assumption of linear regressions, they were square root transformed.

p < .1

p < .05

p < .001

Regression Analyses Predicting CDI Comprehension.

Table 5 shows the results of regression models predicting children’s CDI comprehension scores at 18 months. In Model 1, 10-month shows+gives were not significantly associated with later CDI comprehension, when controlling for parent education and concurrent vocabulary. In Model 2, 14-month points were marginally associated with later comprehension, with parent education and 14-month vocabulary controlled, b = 3.83, S.E. = 1.91, p = .053, β = 0.34. In Model 3, 16-month points were not associated with later comprehension, but 16-month vocabulary was marginally predictive of the outcome variable, b = 0.76, S.E. = 0.42, p = .079, β = 0.35. In Model 4, when 10-month shows+gives and 14-month points were entered simultaneously in the same model, only 14-month points predicted later comprehension, b = 4.38, S.E. = 1.86, p = .024, β = 0.39.

Table 5.

Regression Models Predicting CDI Comprehension Scores at 18 Months Using Different Types of Early Deictic Gestures

| CDI Comprehension Parameter Estimate (SE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Intercept | 36.82 (26.54) | 84.87** (26.80) | 53.65* (25.51) | 95.65*** (25.09) |

| Parent Education | 0.54 (1.56) | −2.45 (1.71) | −0.53 (1.63) | −3.07 (1.64) |

| Concurrent Vocabulary | 1.32** (0.38) | 1.04 (0.94) | 0.76~ (0.42) | |

| 10-month Shows+Gives | 3.33 (3.49) | 1.86 (3.91) | ||

| 14-month Points | 3.83~ (1.91) | 4.38* (1.86) | ||

| 16-month Points | 1.82 (2.35) | |||

| N | 40 | 38 | 37 | 38 |

| R2 (%) | 28.8 | 20.5 | 20.7 | 18.2 |

Note. Because gesture variables were not normally distributed, violating the multivariate normality assumption of linear regressions, they were square root transformed.

p < .1

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Summarizing our findings on the associations between gesture and language, we found that at 10 months, children’s shows+gives predicted 18-month expressive language scores on both the standardized (Mullen) and parent report (CDI production) measures and that at 14 months, children’s points were associated with the language production outcomes (Mullen and CDI production). By 16 months, children’s speech was most related to later expressive language scores. The effects of the different gesture types were not as evident when predicting later CDI comprehension scores.

Do Parents Provide More Responses to Shows+Gives vs. Points?

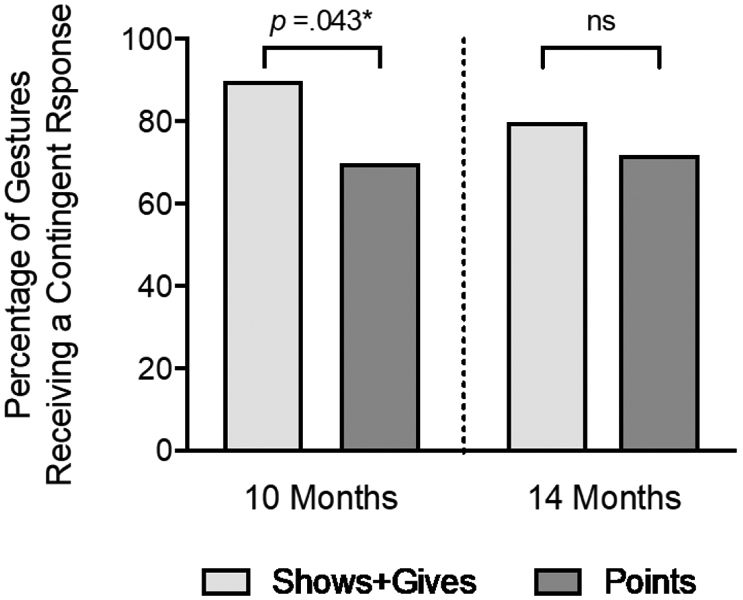

Last, we conducted exploratory analyses to compare parents’ contingent responses to shows+gives and to points at 10 and 14 months, as we hypothesized that parental responsiveness might differ as a function of child gesture type and might serve as a potential mechanism underlying the differential relations between the different gesture types and language outcomes in children. Figure 3 displays the percentages of parental contingent responses to shows+gives versus points at 10 and 14 months. At 10 months, parents responded to a significantly higher proportion of shows+gives (M = 90%; SD = 26%) than to points (M = 70%; SD = 26%), t(29) = 2.11, p = .043. At 14 months, parents responded to shows+gives (M = 80%; SD = 29%) and points (M = 72%; SD = 28%) at similar rates. We also explored the relations between parents’ contingent responses and children’s language outcomes at 18 months. Parents’ contingent responses to 10-month shows+gives were significantly positively correlated with children’s 18-month CDI production (r = .69, p = .009) and comprehension (r = .61, p = .028) scores. There were no other significant correlations. Finally, given the nature of the intervention design in our original study (Rowe & Leech, 2019), we checked to see if the intervention had any effect on parents’ contingent responsiveness. We found that there were no significant group differences in responsiveness to children’s shows+gives and points between parents in the intervention group and those in the control group.

Figure 3.

Comparison of percentages of child shows+gives (light gray) and points (dark gray) that received a contingent response from parents at 10 months and 14 months.

Discussion

In both typical and atypical development, there has been a predominant focus on pointing as a predictor of language (Boundy et al., 2016; Manwaring et al., 2018). In the present study, we examined the emergence and use of other deictic gestures such as shows and gives, along with points, between 10 and 16 months and investigated the ages at which they were associated with later language skills at 18 months. Our key finding is that there seems to be a developmental progression where show+give gestures are predictive of language outcomes several months before pointing gestures are. And once pointing gestures predict language outcomes, show+give gestures no longer do so. Specifically, at 10 months, use of shows+gives predicted later use of points and was a better predictor of 18-month language than points; yet at 14 months, points were more related to later language than shows+gives. By 16 months, children’s use of speech in the interaction, not gesture, predicted 18-month language scores. Also, there was some preliminary evidence indicating that parent responsiveness differed based on child gesture type. Below we discuss each of these findings.

Our finding that shows+gives at 10 months related to later points replicates the finding of Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2015), who found shows+gives at 10-11 months predicted subsequent points. There are a few methodological differences between the present study and Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2015) worth mentioning. One obvious difference is that the sample consisted of children mostly from middle class backgrounds in the UK in Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2015), while our sample was comprised of children from socioeconomically diverse backgrounds in the US. Another difference is that the gestures were examined in a quasi-naturalistic context (e.g., points were elicited from infants in a laboratory setting) in Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2015), whereas spontaneous gestures were observed during parent-child interactions in home environments in the present study. Despite these differences from Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2015), we found a consistent finding that shows+gives around age 10 months predicted later points, adding more support to the hypothesis that shows+gives may be a developmental precursor to points.

One explanation for the association between shows+gives and later points is that infants may use shows+gives to draw attention to proximal reference around 10 months, and as they develop more advanced motor skills to use index-finger pointing, they may indicate objects with more distal references. What remains unclear, however, is that whether shows and gives, which were examined together in the present study and Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2015), make unique contributions to the development of points. In a fine-grained analysis of show and give gestures, Boundy et al. (2016) found that different micro-behaviors predicted show and give gestures, suggesting they may be two distinct behaviors. For example, an infant’s raised arm was associated with more shows than gives, and an inverted handshape was associated with more gives than shows. Therefore, future research should determine if early shows or gives better account for variability in later points and language. Moreover, a recent study by Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2020) reported a significant positive relation between shows+gives and later points in the English, but not Bengali and Chinese samples. Thus, future research is needed to uncover the degree to which shows+gives predict points in different cultural groups.

Extending the previous research on the link between shows+gives and later points, we also found that 10-month shows+gives were associated with subsequent language skills (Mullen expressive language and CDI production) at 18 months, over and above the factors previously identified as predictors of language (i.e., parent education and child vocabulary). This finding is consistent with Donnellan et al. (2020), who found that show gestures were the best gestural predictor of later expressive vocabulary. Importantly, the effects of 10-month shows+gives remained significant when 10-month shows+gives and 14-month points were entered simultaneously as predictors in the same model. These results demonstrate that shows+gives predict later language skills, even with 14-month pointing, which has been identified as a reliable predictor of language in the literature (e.g., Rowe et al., 2008), controlled and vice versa. By contrast, 10-month points were not predictive of later language. Taken together, these findings add to a growing number of studies, suggesting that in the first year of life, points may not always be the best gestural indicator of language outcomes (Donnellan et al., 2020; McGillion et al., 2017). Rather, the predictive value of different deictic gestures may depend on the developmental timing in infancy.

There are multiple reasons why gesture might predict language. One potential mechanism is that gestures may elicit informative contingent responses from parents that contribute to language development. In the current study, we were interested in understanding whether parent responsiveness differed across gesture types. In fact, we found that parents contingently responded to a significantly higher percentage of children’s shows+gives than to points at 10 months, which provides some preliminary evidence for this potential mechanism. Cameron-Faulkner et al. (2015) similarly reported that parents often commented or acted upon an object when an infant showed or gave them the object. Thus, it may be that the association between children’s early shows+gives and later language are explained by parents’ responses targeted to the child’s focus of attention. Conducting mediation analyses with larger sample sizes is a viable direction for future research to determine whether parental responsiveness indeed mediates the association between early shows+gives and language development. While not examined in the current study, it is also possible that parents’ translations of children’s gestures into words (e.g., child shows a cup, and parent says, “it’s a cup!”), in particular, may help children acquire vocabulary. In fact, studies with both typically and atypically developing populations have found that parents translate the majority of their children’s gestures into words and that these translations subsequently benefit children’s vocabulary development (Dimitrova et al., 2016; Goldin-Meadow et al., 2007; Masur, 1982). Future work should examine whether parents’ translations of child gestures differ as a function of gesture types and if so, whether they have differential, facilitative effects for children’s language development. For example, Leezenbaum et al. (2014) found that maternal translations of children’s 13-month shows and points were significantly positively correlated with children’s 18-month word production while parental translations of the gives and requests were not, among dyads involving infants at high and low risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Our finding that 10-month shows+gives predicted language production, but not comprehension, at 18 months is similar to that of a recent study (Cameron-Faulkner et al., 2020), which reported that early gestures at 10-12 months had a positive relation with vocabulary production, but not comprehension, at 18 months in their English sample; however, a significant relation was found in their Chinese sample (also see Vogt & Mastin, 2013 for within-cultural differences in the association between early gesture directed to infants and later language between urban and rural communities in Mozambique). Altogether, these findings suggest that the potential effects of early gestures may differ depending on language modalities (production vs. comprehension) and/or cultural groups, calling for further research in this area.

Whereas shows+gives best predicted later language at an earlier age (10-months), points were a better predictor of later language skills than shows+gives at 14 months. The finding demonstrating the link between 14-month points and later language is consistent with a robust body of previous studies (Colonnesi et al., 2010; Rowe et al., 2008; Rowe & Goldin-Meadow, 2009). One possible explanation for the connection between points and later language is that children of this age use more points than shows+gives. In fact, points were produced more than twice as frequently as shows+gives at 14 months (Mpoints = 8.56, Mshows+gives = 3.70; Table 2), but not at 10 or 12 months. Nevertheless, parent responsiveness to shows+gives vs. points did not differ at 14 months, indicating that parents were similarly responsive to shows+gives and to points. It is possible, then, that more frequent points, which lead to parent responses, facilitate increased language learning opportunities.

Collectively, these results highlight that there are multiple mechanisms (e.g., social, cognitive) by which gestures could play a role in language development. As previously noted, one mechanism may be that children’s gestures elicit helpful responses from parents (Goldin-Meadow et al., 2007; Olson & Masur, 2015). In fact, in the current study we found that 10-month shows+gives received a higher proportion of parental contingent responses than 10-month points and that 10-month shows+gives were associated with higher 18-month language skills. Alternatively, the act of gesturing itself could be part of the learning mechanism (Goldin-Meadow & Alibali, 2013; Iverson & Goldin-Meadow, 2005; Rowe et al., 2008). For example, child gesture at 14 months predicted later vocabulary at 42 months, over and above other potent predictors such as socioeconomic status and child speech (Rowe et al., 2008). We similarly found in the present study that points at 14 months better predicted later language than other predictors. Thus, these findings suggest that gestures could provide children with the opportunity to practice ideas that they are not yet able to convey via speech, which could then pave the way for language acquisition (Goldin-Meadow & Alibali, 2013). In sum, research suggests that there are (at least) social and cognitive mechanisms by which gesture could facilitate language development, and our results provide evidence that these mechanisms may operate differently at various ages and with different gesture types.

Finally, we found that at 16 months, child speech, but not gesture, best predicted later language skills. Thus, by around this age, points may be a less useful indicator of future language skills relative to the child’s actual language production, which varies extensively across children by 16 months. At this age, children are better able to express themselves verbally and may depend less on gestures to communicate. The fact that children produced, on average, six more words at 16 months than at 14 months, but did not show any increase in their points (Table 2) provides potential evidence to this explanation.

Overall, these findings are consistent with a developmental scenario in which shows+gives are most related to later language early in development (10-months), points become more related to language in the second year of life (14-months), and speech best predicts language when children have larger spoken vocabularies (16-months+). Thus, across infancy, different types of deictic gestures provide a window into later vocabulary skills at different time points in early development. It should be noted, however, that we are not arguing that different gesture types relate to later language at these exact ages. Given the nature of data collected between 10 and 16 months at every two months in the present study, we approached the data by examining the production of shows+gives and points at different time points (i.e., 10, 12, 14, and 16 months). Therefore, it is possible that the exact ages at which shows+gives and points best predict later language may not be precisely 10 and 14 months, for instance. Alternative approaches, such as denser sampling of data and thorough analysis of gestures over time, will allow more careful characterization of developmental trajectories of gestures in relation to language development, and could speak to the important issue of whether shows and gives are replaced or supplemented by pointing gestures across early development. For example, when looking at the subset of children who produced shows+gives at 10 months (Supplemental Information, Table S3), they continued to produce shows+gives at similar rates even when they started to use more points around 14 months. Therefore, shows+gives may be supplemented, rather than replaced, by points over the course of time, although this needs to be replicated with larger samples. It is also worth mentioning that previous research has also examined production of pointing gestures in combination with speech (gesture+speech combinations) as predictive of syntactic development. The timing of those findings differed, with the gesture+speech combinations at 18 months predictive of later spoken syntax (Rowe & Goldin-Meadow, 2009).

While the present study extends previous work by using a socioeconomically diverse community sample of families and identifying differential effects of different deictic gestures in predicting language skills, it has several limitations that should be addressed in future studies. First, this study had a larger number of participants than previous similar studies, but the present sample is still limited, so these findings should be replicated with larger samples in future research. A related point is that the number of children who produced shows+gives at 10 months was low (n = 16 of the 47 children); therefore, our findings on the relation between 10-month shows+gives and 18-month language may not be generalizable to all children. Second, language skills were not measured beyond 18 months, which limits our ability to assess the predictive value of gestures beyond this point, especially shows+gives that have been less explored in the literature, in later stages of language development. Future investigations should thus determine whether the effects of shows+gives predict long-term language outcomes. Third, the present findings of the associations among shows+gives, points, and language in typical development provide a platform for further research to elucidate these relations in atypical development, such as ASD. Examining shows+gives vs. points in clinical populations could reveal important insights about their specificity and sensitivity of as predictors of language. For example, a review paper on deictic gesture use in children with or at risk for ASD reported that reduced showing was a more specific marker of the disorder than pointing (Manwaring et al., 2018), demonstrating the importance of studying shows+gives and other non-pointing gestures, which have been relatively overlooked in the literature, in relation to language development in at-risk populations. Next, while we did not exclude fathers or other caregivers from participating in the study, the majority of the parents who participated in our study were mothers (98%), and therefore, our findings about the parent responses may not generalize to other important caregivers in children’s lives such as fathers, nannies, and day care teachers. Given there is limited research about the contribution of input of caregivers other than ‘mothers,’ an important avenue for future research will be to expand reach to a more diverse caregiver pool. Also, we examined children’s gesture development using a 15-minute semi-structured play session, which may not capture typical behaviors produced throughout the day (Abels et al., 2017) and may be more similar to the “peak” interaction points during a day (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2017); therefore, a future study may consider utilizing daylong recordings that can provide more ecologically valid and naturalistic data from diverse communities (Cychosz et al., 2020). Finally, our coding criteria for show and give gestures was broad and did not examine any associated micro-behaviors that can help classify different gestures quantitatively (Boundy et al., 2016). Relatedly, given the heterogeneity in the definition of show and give gestures in the literature (Supplemental Information, Table S1), future research should employ consistent operationalization and measurement of the gestural types that can lead to a clear understanding of the contribution of different deictic gestures in children’s language learning.

In conclusion, this study examined the developmental course of infants’ use of shows, gives, and points between 10 and 16 months and assessed the extent to which these gestures differentially predicted language skills at 18 months. At 10 months, shows and gives best predicted later language skills, while at 14 and 16 months, points and speech best predicted later language. Taken together, these findings suggest that early show and give gestures are important factors to consider in studying children’s communicative and language development (Boundy et al., 2016; Moreno-Núøez et al., 2020). Furthermore, these results indicate that early show and give gestures may serve as useful indices of language outcomes and may help identify children, especially those in need of intervention, earlier in life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This work was funded by grant R21HD078771 from the NICHD to Rowe. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with regard to the funding source for this study. We would like to thank all the families and staffs who contributed to this project including: Virginia Salo, Molly McDowell, Kaitlin Herbert, Haley Kittel, Stone Dawson, Emily Dowling, Grace Zielinski, Meishi Haslip, Jennifer McCatharn, Rebecca Goldberg, Emma Gulley and Julian Blatt. We also thank Rachel M. Hantman for helpful comments and edits on the previous version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

In the present study, give gestures were defined as holding out an object for a partner to take as defined in some previous studies (e.g., Cameron-Faulkner et al., 2015). However, it should be noted that there are differences in the definition of give gestures in the literature; for example, gives were operationalized as requesting for objects i.e., “extending an empty open palm toward a ball to convey ‘give ball’” (p. 329) in Özçalışkan et al., 2017, whereas such gestures were coded as “palm-up” gestures in our data and not examined in this study.

Descriptive statistics on shows+gives by intervention status are provided in Supplemental Information, Table S2. There were no significant group differences in shows+gives between the intervention and control groups at 10, 12, 14, and 16 months. Descriptive statistics and group comparisons on point gestures can be found in our previous work focusing on the effects of intervention on point gestures (Rowe & Leech, 2019). Children whose parents received the intervention produced significantly more points, compared to children of control parents at 12 months; however, the intervention effects on points were not observed at any other ages.

References

- Abels M, Papaligoura Z, Lamm B, & Yovsi RD (2017). How usual is “play as you usually would”? A comparison of naturalistic mother-infant interactions with videorecorded play sessions in three cultural communities. Child Development Research, 2017, e7842030. 10.1155/2017/7842030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aureli T, Spinelli M, Fasolo M, Garito MC, Perucchini P, & D’Odorico L (2017). The pointing–vocal coupling progression in the first half of the second year of life. Infancy, 22(6), 801–818. 10.1111/infa.12181 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates E, Benigni L, Bretherton I, Camaioni L, & Volterra V (1979). Cognition and communication from nine to thirteen months: Correlational findings. In The emergence of symbols: Cognition and communication in infancy (pp. 69–140). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bates E (1976). Language and Context: The Acquisition of Pragmatics. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bates Elizabeth, Camaioni L, & Volterra V (1975). The acquisition of performatives prior to speech. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly of Behavior and Development, 21(3), 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Boundy L, Cameron-Faulkner T, & Theakston A (2016). Exploring early communicative behaviours: A fine-grained analysis of infant shows and gives. Infant Behavior & Development, 44, 86–97. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron-Faulkner T, Theakston A, Lieven E, & Tomasello M (2015). The relationship between infant holdout and gives, and pointing. Infancy, 20(5), 576–586. 10.1111/infa.12085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capone NC, & McGregor KK (2004). Gesture development: A review for clinical and research practices. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 47(1), 173–186. 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M, Nagell K, Tomasello M, Butterworth G, & Moore C (1998). Social cognition, joint attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 63(4), i–174. JSTOR. 10.2307/1166214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements C, & Chawarska K (2010). Beyond pointing: Development of the 'showing' gesture in children with autism spectrum disorders. Yale Review of Undergraduate Research in Psychology, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Colonnesi C, Stams GJJM, Koster I, & Noom MJ (2010). The relation between pointing and language development: A meta-analysis. Developmental Review, 30(4), 352–366. 10.1016/j.dr.2010.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cychosz M, Romeo R, Soderstrom M, Scaff C, Ganek H, Cristia A, Casillas M, de Barbaro K, Bang JY, & Weisleder A (2020). Longform recordings of everyday life: Ethics for best practices. Behavior Research Methods. 10.3758/s13428-020-01365-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova N, Özçalışkan Ş, & Adamson LB (2016). Parents’ translations of child gesture facilitate word learning in children with autism, Down syndrome and typical development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 221–231. 10.1007/s10803-015-2566-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan E, Bannard C, McGillion ML, Slocombe KE, & Matthews D (2020). Infants’ intentionally communicative vocalizations elicit responses from caregivers and are the best predictors of the transition to language: A longitudinal investigation of infants’ vocalizations, gestures and word production. Developmental Science, 23(1), e12843. 10.1111/desc.12843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand VN, Loe IM, Yeatman JD, & Feldman HM (2013). Effects of early language, speech, and cognition on later reading: A mediation analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 4. 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, & Pethick SJ (1994). Variability in early communicative development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(5), 1–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Marchman VA, Thal DJ, Dale PS, Reznick JS, & Bates E (2007). MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S (2007). Pointing sets the stage for learning language—And creating language. Child Development, 78(3), 741–745. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, & Alibali MW (2013). Gesture’s role in speaking, learning, and creating language. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 257–283. 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin-Meadow S, Goodrich W, Sauer E, & Iverson J (2007). Young children use their hands to tell their mothers what to say. Developmental Science, 10(6), 778–785. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek K, Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Owen MT, Golinkoff RM, Pace A, Yust PKS, & Suma K (2015). The contribution of early communication quality to low-income children’s language success. Psychological Science, 26(7), 1071–1083. 10.1177/0956797615581493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E (2003). The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development, 74(5), 1368–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J, Haight W, Bryk A, Seltzer M, & Lyons T (1991). Early vocabulary growth: Relation to language input and gender. Developmental Psychology, 27(2), 236–248. 10.1037/0012-1649.27.2.236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J, Waterfall H, Vasilyeva M, Vevea J, & Hedges LV (2010). Sources of variability in children’s language growth. Cognitive Psychology, 61(4), 343–365. 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2010.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson JM, & Goldin-Meadow S (2005). Gesture paves the way for language development. Psychological Science, 16(5), 367–371. 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.01542.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leezenbaum NB, Campbell SB, Butler D, & Iverson JM (2014). Maternal verbal responses to communication of infants at low and heightened risk of autism. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 18(6), 694–703. 10.1177/1362361313491327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B (2000). The CHILDES Project: Tools for analyzing talk. (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Manwaring SS, Stevens AL, Mowdood A, & Lackey M (2018). A scoping review of deictic gesture use in toddlers with or at-risk for autism spectrum disorder. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 3, 2396941517751891. 10.1177/2396941517751891 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masur EF (1982). Mothers’ responses to infants’ object-related gestures: Influences on lexical development. Journal of Child Language, 9(1), 23–30. 10.1017/S0305000900003585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillion M, Herbert JS, Pine J, Vihman M, dePaolis R, Keren-Portnoy T, & Matthews D (2017). What paves the way to conventional language? The predictive value of babble, pointing, and socioeconomic status. Child Development, 88(1), 156–166. 10.1111/cdev.12671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Núøez A, Rodríguez C, & Miranda-Zapata E (2020). Getting away from the point: The emergence of ostensive gestures and their functions. Journal of Child Language, 47(3), 556–578. 10.1017/S0305000919000606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen EM (1995). Mullen Scales of Early Learning (AGS). American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Olson J, & Masur EF (2015). Mothers’ labeling responses to infants’ gestures predict vocabulary outcomes. Journal of Child Language, 42(6), 1289–1311. 10.1017/S0305000914000828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan Ş, Adamson LB, & Dimitrova N (2016). Early deictic but not other gestures predict later vocabulary in both typical development and autism. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 20(6), 754–763. 10.1177/1362361315605921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özçalışkan Ş., Adamson LB, Dimitrova N, & Baumann S (2017). Do parents model gestures differently when children’s gestures differ? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–16. 10.1007/s10803-017-3411-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace A, Alper R, Burchinal MR, Golinkoff RM, & Hirsh-Pasek K (2019). Measuring success: Within and cross-domain predictors of academic and social trajectories in elementary school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 46, 112–125. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe ML, & Goldin-Meadow S (2009). Early gesture selectively predicts later language learning. Developmental Science, 12(1), 182–187. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00764.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe ML, & Leech KA (2019). A parent intervention with a growth mindset approach improves children’s early gesture and vocabulary development. Developmental Science, 22(4), e12792. 10.1111/desc.12792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe ML, Özçalişkan Ş., & Goldin-Meadow S (2008). Learning words by hand: Gesture’s role in predicting vocabulary development. First Language, 28(2), 182–199. 10.1177/0142723707088310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbott MR, Nelson CA, & Tager-Flusberg H (2016). Maternal vocal feedback to 9-month-old infant siblings of children with ASD. Autism Research, 9(4), 460–470. psyh. 10.1002/aur.1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Kuchirko Y, Luo R, Escobar K, & Bornstein MH (2017). Power in methods: Language to infants in structured and naturalistic contexts. Developmental Science, 20(6). 10.1111/desc.12456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandell DL (1979). A microanalysis of toddlers’ social interaction with mothers and fathers. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 134(2), 299–312. 10.1080/00221325.1979.10534063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt P, & Mastin JD (2013). Rural and urban differences in language socialization and early vocabulary development in Mozambique. Proceedings of the 35th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 3787–3792. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.