Summary

Regulatory T cells (Treg) prevent the migration of effector T cells toward sites of inflammation, thereby limiting disease progression. We investigated this aspect of Treg function using psoriatic arthritis (PsA) as an exemplar of chronic inflammation. Patients with PsA had an increased Th17:Treg ratio which was reversed by anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. Utilizing an in vitro migration assay, Treg from patients with PsA treated with conventional therapy paradoxically boosted CCR6+ effector T-cell (a surrogate for Th17) migration toward CCL20. In contrast, Treg from patients with PsA treated with anti-TNF suppressed CCL20-driven effector T-cell migration. The boosting effect of TNF blockade upon Treg suppression of migration was accompanied by increased effector T-cell CCL20 production and enhanced interaction between Treg and effector T cells. This study provides mechanistic insight into Treg modulation of effector T-cell migration in patients with chronic inflammation and how this can be targeted by therapy.

Subject areas: biological sciences, immunology, immune system disorder

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A transwell assay can measure Treg control of effector T-cell migration

-

•

Treg enhanced effector T-cell migration toward CCL20 in psoriatic arthritis

-

•

Anti-TNF induced Treg suppressed effector T-cell migration in psoriatic arthritis

-

•

Increased Th17:Treg ratio was reversed by anti-TNF in psoriatic arthritis

Biological sciences; Immunology; Immune system disorder

Introduction

CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) play a critical role in maintaining autoimmunity through limiting effector T-cell proliferation and cytokine production (Miyara et al., 2014). Analysis of Treg function in humans has been dominated by in vitro assays measuring suppression of effector T-cell proliferation and more recently inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine production. A less well documented but potentially important function is the ability of Treg to inhibit effector T-cell migration, which has been explored in murine models of inflammation (Paust et al., 2016; Ring et al., 2006; Tischner et al., 2006). Several studies have demonstrated the important role of Treg chemokine receptor expression in guiding Treg to sites of inflammation (Afshar et al., 2013; Ding et al., 2012). However, how Treg control effector T-cell migration in patients with chronic inflammatory disease and the impact of therapy remain unknown.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory condition, which develops in 10-30% of patients with psoriasis (Durham et al., 2015). CCR6-mediated Th17 migration is thought to play an important role in the pathogenesis of the disease, and Th17 cells have been detected at increased numbers in synovial fluid and peripheral blood of these patients (Benham et al., 2013). The anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibody secukinumab has demonstrated efficacy in treating PsA validating IL-17 as an important driver of disease (McInnes et al., 2015). Therefore, we utilized an in vitro assay to study inhibition of CCR6+ effector T-cell migration by Treg as a surrogate of Treg suppression of T-cell migration in human inflammation and applied this assay to samples from patients with PsA. We hypothesized that Treg would be impaired in their ability to control CCR6+ effector T cell, as a surrogate indicator of Th17 (Annunziato et al., 2007), migration in PsA, thereby failing to prevent the accumulation of IL-17 within inflamed joints.

Results

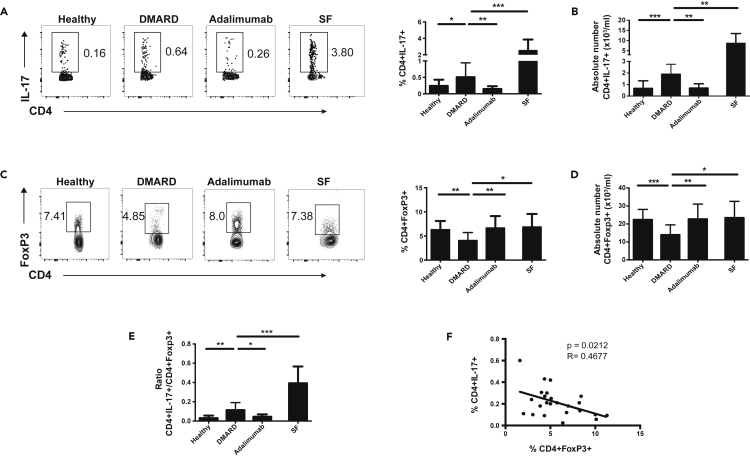

The Th17:Treg ratio was increased in patients with psoriatic arthritis but reversed by anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy

The percentage of CD4+IL-17+ T cells was greater in the peripheral blood of PsA patients (Table S1) receiving conventional therapy (disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, DMARD) compared to healthy controls (Figure 1A). This increase in Th17 in patients with PsA was reversed by anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy (adalimumab) (Figure 1A). The percentage (Figure 1A) and absolute number (Figure 1B) of CD4+IL-17+ cells in synovial fluid were significantly elevated compared to peripheral blood from DMARD-treated patients with PsA. In contrast, CD4+FoxP3+ Treg frequency and the number were reduced in the peripheral blood of DMARD-treated patients compared to healthy controls (Figures 1C and 1D) which has been noted before (Wang et al., 2020). Peripheral blood Treg numbers were restored to normal in patients treated with anti-TNF (Figures 1C and 1D). Higher numbers of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg were present within synovial fluid compared to peripheral blood from patients with PsA treated with conventional therapy (Figures 1C and 1D). These changes in Treg and Th17 numbers in PsA led to a heightened Th17:Treg ratio in the peripheral blood of DMARD-treated patients with PsA which was substantially reduced by anti-TNF therapy (Figure 1E). Indeed, there was a negative correlation between the frequency of Th17 and Treg in the peripheral blood of patients with PsA (Figure 1F). There was also a marked increase in the Th17:Treg ratio in PsA synovial fluid compared to the peripheral blood (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Anti-TNF therapy reversed the increased Th17:Treg ratio in patients with psoriatic arthritis

(A–D) Peripheral blood was taken from healthy individuals, DMARD-, and anti-TNF (adalimumab)-treated patients with PsA, and synovial fluid (SF) was harvested from patients with PsA where available. Representative and cumulative data indicating the percentage (A) and absolute numbers (B) of CD4+IL-17+ and (C and D) CD4+FoxP3+ T cells detected by flow cytometry in peripheral blood or synovial fluid.

(E) Ratio of CD4+IL-17+: CD4+FoxP3+ T cells in healthy individuals and patients with PsA.

(F) Correlation between CD4+Foxp3+ Treg and CD4+IL-17+ in patients with PsA (DMARD and anti-TNF treated). Data are represented as mean ± SD from 17 healthy individuals, 10 DMARD-, 14 adalimumab-treated patients, and 4 synovial fluid samples. Mann-Whitney U tests and unpaired t tests were used to determine significance. p < 0.05∗, p < 0.01∗∗, p < 0.001∗∗∗.

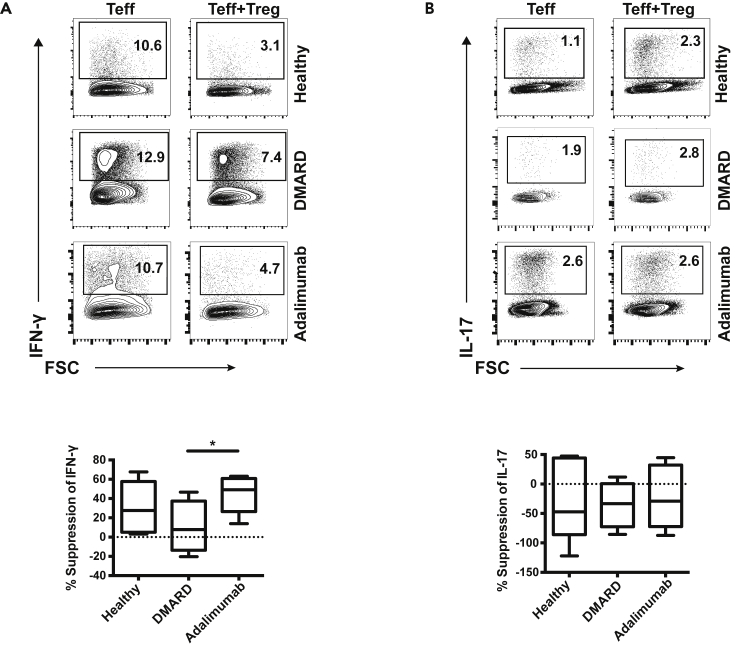

Treg from patients with PsA treated with anti-TNF were more potent suppressors of effector T-cell IFN-γ production compared to Treg from patients with PsA receiving conventional therapy

We next tested whether PsA Treg could limit effector T-cell cytokine production. In vitro suppression assays were performed using effector T cells and Treg purified from peripheral blood (Figure S1). The percentage suppression of IFN-γ effector T-cell production by Treg from adalimumab-treated patients with PsA was greater than their counterparts from DMARD-treated patients (Figure 2A). Healthy Tregs were unable to suppress effector T-cell IL-17 production, and both DMARD and adalimumab PsA Treg were similarly impaired (Figure 2B). Indeed, IL-17 production tended to increase when Treg were added to effector T cells in the presence of monocytes.

Figure 2.

Anti-TNF therapy enhanced Treg suppression of effector T-cell IFN-γ production in psoriatic arthritis

CD4+Treg (Treg: CD4+CD25highCD127-), CD4+ effector T cells (Teff: CD4+CD25−CD127+), and CD14+ monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood of healthy individuals, DMARD-, and adalimumab-treated patients with PsA. Teff were stained with CFSE, monocytes were stained with PKH-26, and Treg was left unlabeled. Teff:Treg:monocytes were cultured at a 3:1:1 ratio with anti-CD3. Representative and cumulative data show percentage suppression of IFN-γ (A) and IL-17 (B) production by effector T cells in the presence of Treg. Data are represented as mean ± SD from healthy individuals (n = 5), DMARD-treated patients with PsA (n = 4), and adalimumab-treated patients with PsA (n = 6). Unpaired t tests were used to determine significance. p < 0.05∗.

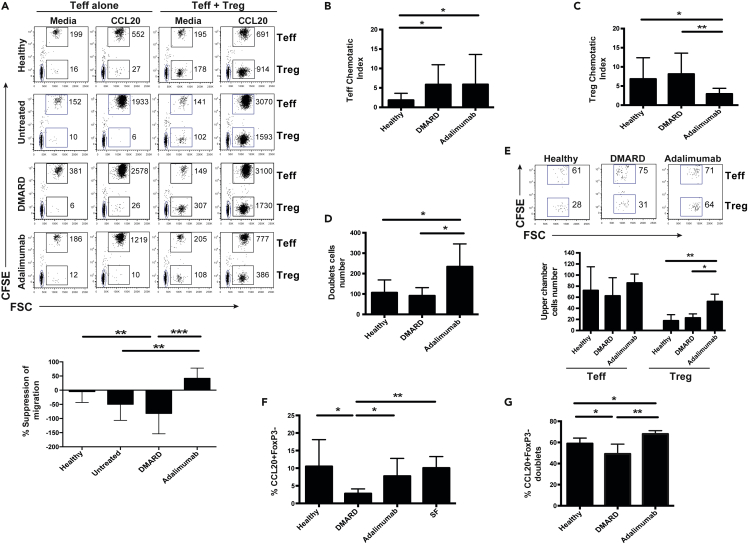

Treg from anti-TNF-treated patients with PsA suppressed effector T-cell migration which was associated with enhanced Treg-effector T-cell interaction

We proceeded to address whether Treg suppressor function extended to limiting effector T-cell migration toward CCL20, which is an essential chemoattractant for CCR6+ Th17 cells (Hirota et al., 2007). We found that healthy Treg had no significant effect on effector T-cell migration toward CCL20 in vitro (Figure 3A). Unexpectedly, Treg from untreated and DMARD-treated patients with PsA enhanced effector T-cell migration. In contrast, Treg from adalimumab-treated patients suppressed effector T-cell migration (Figure 3A). The chemotactic index of effector T cells, in the absence of Treg, in both DMARD- and adalimumab-treated patients with PsA was significantly higher than that in healthy controls (Figure 3B). Treg migration from adalimumab-treated patients, in the presence of their corresponding effector T cells, was significantly reduced compared to Treg from DMARD-treated patients with PsA and healthy controls (Figure 3C). Thus, the ratio of effector T cell to Treg migration was significantly increased in patients treated with adalimumab compared to DMARD-treated patients and healthy individuals (Figure S2B). We used forward and side scatter analysis to identify cell doublets as a surrogate for Treg and effector T-cell interaction in the upper chamber of the transwell (Figure S2C). The upper compartment of the transwell contained significantly more cell doublets when Treg and effector T cells from adalimumab-treated patients were co-cultured, compared to T cells from patients with PsA receiving DMARDs and healthy controls (Figures 3D and S2C). Effector T cells and Treg were added at a 3:1 ratio to the top compartment of the transwell, but these proportions shifted toward parity after co-culture when effector T cells and Treg were isolated from adalimumab-treated patients (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Regulatory T cells enhanced CCR6-driven effector T-cell migration in psoriatic arthritis which was reversed by anti-TNF

(A–E) CD4+Treg (Treg: CD4+CD25highCD127-) and CD4+ effector T cells (Teff: CD4+CD25−CD127+) were purified from peripheral blood of healthy individuals, untreated, DMARD-, and adalimumab-treated patients with PsA. Effector T cells were stained with CFSE, and Treg were left unlabeled. Effector T cells (150,000) were placed in the upper compartment of a transwell (with CCL20 in the lower chamber) either alone or with CD4+ Treg (effector T cell: Treg ratio was 3:1) and co-cultured for 3 hr.

(A) Representative flow cytometry plot showing the number of effector T cells migrating toward CCL20 (or media alone) in the presence or absence of Treg. Cumulative data represented as mean ± SD show the percentage suppression of migration of effector T cells by Treg in the different groups. Healthy individuals n = 9, untreated PsA n = 5, DMARD-treated patients with PsA n = 6, adalimumab-treated patients with PsA n = 9.

(B) Chemotactic index of effector T cells migrating toward CCL20 in the absence of Treg from healthy individuals, DMARD-, and adalimumab-treated patients with PsA.

(C) Chemotactic index of Treg in the presence of their matched effector T cells.

(D-E) The upper chambers of the transwells containing effector T cells and Treg from the chemotaxis assays were harvested, and cell doublets were identified based on forward and side scatter. Cumulative data showing (D) cell doublet number, (E) with effector T cells and Treg separately enumerated in the cell doublets contained within the upper chamber, with a representative flow cytometry plot gated on cell doublets discriminating effector T cell and Treg based on CFSE staining of effector T cells. Healthy individuals n = 5, DMARD-treated patients with PsA n = 4, adalimumab-treated patients with PsA n = 5.

(F) Expression of CCL20 in peripheral blood and synovial fluid within effector T cells, healthy individuals n = 12, DMARD-treated patients with PsA n = 6, adalimumab-treated patients with PsA n = 10.

(G) Percentage of CCL20 producing effector T cells present in the cell doublets from the upper compartment of the transwell. Healthy individuals n = 5, DMARD-treated patients with PsA n = 5, adalimumab-treated patients with PsA n = 5. Unpaired t-tests were used to determine significance. p < 0.05∗, p < 0.01∗∗, p < 0.001∗∗∗.

We postulated that the production of CCL20 by Th17 cells (Hirota et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2007) in the upper chamber was competing with the CCL20 in the lower compartment to attract the co-cultured Treg. Effector T cells from patients treated with adalimumab showed increased CCL20 production compared to DMARD-treated patients, reaching similar levels found in effector T cells from synovial fluid (Figure 3F). Effector T cells in the doublets analyzed from the upper chamber of the transwell had higher expression of CCL20 compared to effector T cells in peripheral blood, with the greatest increase in those from adalimumab-treated patients (Figure 3G). The frequency of CCR6+ Treg (and CCR6 Treg expression) was significantly reduced in the peripheral blood of adalimumab-treated patients compared to untreated and DMARD PsA (Figures S3B and S3D). Similar levels of frequency and expression of CCR6 were found in effector T cells in PsA irrespective of treatment (Figures S3A and S3C).

Discussion

The main finding of these data is that Treg differentially modulates CCR6-mediated cell migration in PsA providing insight into the properties of Treg in an inflammatory disease and the impact of therapy. Treg from DMARD-treated patients with PsA promoted CCR6-mediated effector T-cell migration toward the chemokine CCL20 which could promote inflammation and worsen disease. In contrast, Treg from anti-TNF-treated patients suppressed CCL20-driven effector T-cell migration. Our data support the hypothesis that the increased interaction between effector T cells and Treg, from anti-TNF-treated patients, in the upper chamber of the transwell reduced the numbers of effector T cells migrating toward the CCL20 in the lower compartment. We postulate that the increased CCL20 production by effector T cells competes with the CCL20 added to the lower compartment, reducing the migration of Treg and promoting the formation of Treg-effector T-cell conjugates, thereby also reducing their own transmigration to the lower chamber. The reduced CCR6 expression on circulating Treg from anti-TNF-treated patients could contribute to their reduced migration toward the distant CCL20 in the bottom compartment of the transwell and may favor an interaction with neighboring CCL20 producing effector T cells. Moreover, the lower CCR6 expression on Treg from patients receiving anti-TNF therapy could account for their heightened suppressive properties, both in respect of inhibiting effector T-cell migration and cytokine production, in light of previous data showing expression of this chemokine receptor can disable Treg function (Kulkarni et al., 2018). It remains unclear where Tregs are exerting their effects on migration of effector T cells. Data from murine models of arthritis suggest that Treg may act in the draining lymph nodes rather than the inflamed joints (or peripheral blood) (Oh et al., 2010; Ohata et al., 2007), which would explain our observations that Th17 cells were reduced in the peripheral blood after anti-TNF therapy.

The enhanced migration of effector T cells driven by Treg in PsA is consistent with the enrichment of Th17 cells in synovial fluid and associated with increased production of IL-17 at the site of inflammation (Benham et al., 2013). This pro-inflammatory effect of Treg in PsA may represent another manifestation of their instability during inflammation, in addition to their well described propensity to release IL-17 (Beriou et al., 2009; Koenen et al., 2008). Treg-accelerated CCR6-mediated Th17 migration, compounded by their inability to control Th17 production which has also been reported in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (McGovern et al., 2012), would likely worsen disease. Indeed, Treg can themselves produce IL-17, which could exacerbate inflammation (Koenen et al., 2008). Of note, anti-TNF did not endow Treg with the ability to suppress IL-17 production by effector T cells, in contrast to patients with RA (McGovern et al., 2012). However, anti-TNF did increase peripheral blood Treg numbers in patients with PsA compared to those treated with conventional therapy reminiscent of findings in RA (McGovern et al., 2012).

Our findings suggesting that changes in effector T-cell chemokine production in anti-TNF-treated patients could modulate the ability of Treg to function at sites of inflammation are reminiscent of the boosting properties of effector T cells upon Treg in a murine model of diabetes (Grinberg-Bleyer et al., 2010). Th17 cells produce CCL20 (Wilson et al., 2007) which could represent a negative feedback mechanism to attract Treg and dampen inflammation. Increased interaction between Treg and effector T cells would likely limit migration into the joint and pro-inflammatory cytokine release. Anti-TNF therapy confers upon Treg the ability to suppress effector T-cell migration as well as more efficient suppression of IFN-γ, revealing a potential mechanism of action for this treatment in PsA. Resistance to Treg suppression by effector T cells may contribute to the differences observed in effector T-cell migration in the presence of Treg from the different patient groups. Additional studies are needed to demonstrate the clinical utility of the in vitro migration assay utilized here as a measure of Treg function in other chronic inflammatory diseases, and whether Treg suppressing effector T cell migration is an important mechanism of action of anti-TNF therapy. Further examination of this axis of regulation could provide new therapeutic avenues to treat PsA as well as extend these findings to other diseases characterized by chronic inflammation.

Limitations of the study

The principle limitation of this research is the use of an in vitro assay to study control of effector T-cell migration by Treg. This was necessary as we wanted to study human Treg rather than utilize an animal model of disease, where relevance to disease is unclear and response to targeted therapy does not always match mechanisms in patients. The findings presented here do not prove that anti-TNF works via Treg suppressing effector T-cell migration. In addition, if Treg is acting in draining lymph nodes to prevent egress of effector T cells into the inflamed joint, it would have been valuable to have data from this tissue. Finally, it would have been useful to study the synovial tissue of patients treated with anti-TNF to ascertain the changes in Treg and Th17 cells, although these patients rarely have synovial fluid due to their response to treatment.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENTS or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-CD4 AF700 | BD Biosciences | Cat#557922; RRID: AB_396943 |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-CD25 PE | BD Biosciences | Cat#555432; RRID: AB_395826 |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-IFN-γ PE-Cy7 | BD Biosciences | Cat#557643; RRID: AB_396760 |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-CCR6 BV605 | Biolegend | Cat#353419; RRID: AB_11124539 |

| Goat Monoclonal anti-IL-17-AF488 | Biolegend | Cat#516604; RRID: AB_10730721 |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-CCL20 PE | R&D Systems | Cat#IC360P; RRID: AB_2071798 |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-FoxP3 efluor 660 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#50-4777-42; RRID: AB_2574219 |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-CD127 APC-efluor 780 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#47-1278-42; RRID: AB_1548674 |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-CD14 PE | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#12-0149-42; RRID: AB_10598367 |

| Mouse Monoclonal anti-CD3 | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#16-0039-81; RRID: AB_468858 |

| Chemicals, peptides, andrecombinantproteins | ||

| Recombinant Human MIP-3α (CCL20) | PeproTech | Cat#300-29A |

| Golgi Stop | BD Biosciences | Cat#554724 |

| Ficoll Paque Plus | Merk | Cat#GE17-1440-02 |

| Phorbol 12-Myristate 13-Acetate | Merk | Cat#P-8139 |

| Ionomycin | Merk | Cat#I0634 |

| PKH-26 | Merk | Cat#CPKH26GL |

| FoxP3 Transcription buffer staining kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#00-5523-00 |

| Live/Dead Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain Kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#L23105 |

| Cell Trace Violet Cell Proliferation CFSE Kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#C34557 |

| OneComp eBeads | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#01-1111-42 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Peripheral blood from patients with psoriatic arthritis | University College London Hospital | N/A |

| Peripheral blood from healthy individuals | University College London Hospital | N/A |

| Software | ||

| FACS DIVA v9.0.0 | BD Bioscences | https://www.bdbiosciences.com/ |

| FlowJo v10.7.1 | BD Biosciences | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| Prism v8 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Michael R. Ehrenstein (m.ehrenstein@ucl.ac.uk)

Materials availability

This study did not generate unique reagents.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

Subjects

Heparinised peripheral blood and synovial fluid were taken from 66 PsA patients (34 male and 32 female patients, mean age: 52.8 years, standard deviation: 14.2 years) (Table S1). Synovial fluid was isolated from patients with active disease on conventional DMARD therapy. Peripheral blood from 38 healthy volunteers were also recruited. Ethical approval was granted by the North London Ethics Committee and written consent was obtained from all patients participating in the study. Patients recruited to the study were either treatment naïve (untreated) or were receiving methotrexate or sulfasalazine (DMARD), or treated with the anti-TNF therapy adalimumab. All other biologic and conventional therapies were excluded from the study.

Method details

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood and synovial fluid mononuclear cells (PBMC and SFMC) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll (Merk) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were stained with Live/Dead Blue (ThermoFisher Scientific) before staining for CD4, CCL20 and CCR6 surface expression. Samples were then fixed/permeabilised using the FoxP3 Transcription buffer staining kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stained for FoxP3 expression. Immune cell phenotyping was performed using an LSR2 or Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and Diva software, version 9.0.0, and analyzed by FlowJo v10.7.1 (BD Bioscences). For intracellular cytokine staining, fresh PBMC and SFMC were stimulated for 4 hours with PMA (40 ng/ml, Merk), Ionomycin (2μg/ml, Merk) and Golgi Stop® (1μg/ml, BD Biosciences). Samples were fixed/permeabilised as above and stained for IL-17 or IFN-γ production.

Treg suppression assay

CD4 Treg (CD25highCD127low), CD4 effector T cells (Teff) (CD25-CD127+) and autologous CD14+ monocytes were purified from freshly isolated PBMC using an Aria Cell Sorter (Figure S1). Monocytes were added to boost IL-17 production (McGovern et al., 2012). Teff were stained with CFSE (ThermoFisher Scientific), and CD14+ monocytes with PKH-26 (Merk). Treg were left unlabeled. Cells were cultured at a ratio of 3:1:1; Teff:Treg:monocytes in the presence of 1 μg/ml anti-CD3 (HIT-3a) for 4 days. Cells were re-stimulated with PMA, Ionomycin and Golgi Stop® and stained for intracellular cytokines as detailed above. Data represented as percentage suppression of Teff IFN-γ or IL-17 production, calculated as: [(% IFN-γ+ or IL-17+ Teff alone - % IFN-γ+ or IL-17+ Teff in presence of Treg)/ % IFN-γ+ or IL-17+ Teff alone] x100.

Treg suppression of migration assay

Treg and effector T cells (Teff) were purified from freshly isolated PBMC using an Aria Cell Sorter as above. Effector T cells were stained with CFSE and cultured at a 3:1 ratio with Treg (1.5 x 105 Teff:0.5 x105 Treg, 50 μl each; in a total volume 100 μl in the top well of a 24-well 5 μm transwell Corning). CCL20 (50 ng/ml, PeproTech) was placed in the bottom compartment in media (600 μl). After 3 hours incubation, the number of migrated cells in the bottom well was enumerated by flow cytometry using beads. Counting beads (20,000/tube, One Comp ebeads, ThermoFisher Scientific) were added to each well and analysis by flow cytometry for each sample was completed after 2000 beads were recorded. The number of migrated effector T cells and Treg were measured by flow cytometry after gating on CFSE+ (Teff) or CFSE- (Treg) cells (Figure S2A). Chemotactic Index = No. cells migrated towards CCL20/no. cells migrated to media alone. Percentage suppression = [(chemotactic index of Teff alone – chemotactic index of Teff in presence of Treg)/chemotactic index of Teff alone] x 100.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the D'Agostino & Pearson omnibus test to assess whether they were normally distributed. Parametric data were analyzed using paired and unpaired t-tests, non-parametric data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U Test. All analyses were performed using Prism software, version 8. A value of p less than 0.05 was considered significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alice Cotton, Ellie Hawkins, and Jesusa Guinto for recruiting patients and collecting the samples at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Jamie Evans (the Rayne Flow Cytometry Facility, UCL) for isolating the T-cell populations using flow cytometry. M.R.E. was supported in part by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and University College London. The project was supported by Versus Arthritis UK grant reference numbers 19823 and 21286.

Author contributions

D.X.N. and H.M.B. share first authorship, with D.X.N. providing the critical experiments to complete the work that H.M.B. initiated. D.X.N, H.M.B., A.N.E., M.R.B., and M.R.E. designed the experiments. D.X.N., H.M.B., A.N.E., and M.R.B. conducted the experiments and undertook the analysis. D.X.N., H.M.B., and M.R.E. wrote the paper with input from A.N.E.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: September 24, 2021

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.102973.

Supplemental information

References

- Afshar R., Strassner J.P., Seung E., Causton B., Cho J.L., Harris R.S., Hamilos D.L., Medoff B.D., Luster A.D. Compartmentalized chemokine-dependent regulatory T-cell inhibition of allergic pulmonary inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;131:1644–1652.e1644. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziato F., Cosmi L., Santarlasci V., Maggi L., Liotta F., Mazzinghi B., Parente E., Fili L., Ferri S., Frosali F. Phenotypic and functional features of human Th17 cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:1849–1861. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham H., Norris P., Goodall J., Wechalekar M.D., FitzGerald O., Szentpetery A., Smith M., Thomas R., Gaston H. Th17 and Th22 cells in psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013;15:R136. doi: 10.1186/ar4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beriou G., Costantino C.M., Ashley C.W., Yang L., Kuchroo V.K., Baecher-Allan C., Hafler D.A. IL-17-producing human peripheral regulatory T cells retain suppressive function. Blood. 2009;113:4240–4249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Xu J., Bromberg J.S. Regulatory T cell migration during an immune response. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durham L.E., Kirkham B.W., Taams L.S. Contribution of the IL-17 pathway to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2015;17:55. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg-Bleyer Y., Saadoun D., Baeyens A., Billiard F., Goldstein J.D., Gregoire S., Martin G.H., Elhage R., Derian N., Carpentier W. Pathogenic T cells have a paradoxical protective effect in murine autoimmune diabetes by boosting Tregs. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:4558–4568. doi: 10.1172/JCI42945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K., Yoshitomi H., Hashimoto M., Maeda S., Teradaira S., Sugimoto N., Yamaguchi T., Nomura T., Ito H., Nakamura T. Preferential recruitment of CCR6-expressing Th17 cells to inflamed joints via CCL20 in rheumatoid arthritis and its animal model. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:2803–2812. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen H.J., Smeets R.L., Vink P.M., van Rijssen E., Boots A.M., Joosten I. Human CD25highFoxp3pos regulatory T cells differentiate into IL-17-producing cells. Blood. 2008;112:2340–2352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni N., Meitei H.T., Sonar S.A., Sharma P.K., Mujeeb V.R., Srivastava S., Boppana R., Lal G. CCR6 signaling inhibits suppressor function of induced-Treg during gut inflammation. J. Autoimmun. 2018;88:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern J.L., Nguyen D.X., Notley C.A., Mauri C., Isenberg D.A., Ehrenstein M.R. Th17 cells are restrained by Treg cells via the inhibition of interleukin-6 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis responding to anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3129–3138. doi: 10.1002/art.34565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes I.B., Mease P.J., Kirkham B., Kavanaugh A., Ritchlin C.T., Rahman P., van der Heijde D., Landewe R., Conaghan P.G., Gottlieb A.B. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyara M., Ito Y., Sakaguchi S. TREG-cell therapies for autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2014;10:543–551. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S., Rankin A.L., Caton A.J. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in autoimmune arthritis. Immunol. Rev. 2010;233:97–111. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohata J., Miura T., Johnson T.A., Hori S., Ziegler S.F., Kohsaka H. Enhanced efficacy of regulatory T cell transfer against increasing resistance, by elevated Foxp3 expression induced in arthritic murine hosts. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2947–2956. doi: 10.1002/art.22846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paust H.J., Riedel J.H., Krebs C.F., Turner J.E., Brix S.R., Krohn S., Velden J., Wiech T., Kaffke A., Peters A. CXCR3+ regulatory T cells control TH1 responses in crescentic GN. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016;27:1933–1942. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring S., Schafer S.C., Mahnke K., Lehr H.A., Enk A.H. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress contact hypersensitivity reactions by blocking influx of effector T cells into inflamed tissue. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36:2981–2992. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischner D., Weishaupt A., van den Brandt J., Muller N., Beyersdorf N., Ip C.W., Toyka K.V., Hunig T., Gold R., Kerkau T. Polyclonal expansion of regulatory T cells interferes with effector cell migration in a model of multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2006;129:2635–2647. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Zhang S.-X., Hao Y.-F., Qiu M.-T., Luo J., Li Y.-Y., Gao C., Li X.-F. The numbers of peripheral regulatory T cells are reduced in patients with psoriatic arthritis and are restored by low-dose interleukin-2. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2020;11 doi: 10.1177/2040622320916014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N.J., Boniface K., Chan J.R., McKenzie B.S., Blumenschein W.M., Mattson J.D., Basham B., Smith K., Chen T., Morel F. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2007;8:950–957. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.