Abstract

Diesel/natural gas (NG) can effectively improve the performance and reduce emissions of the reactivity-controlled compression ignition (RCCI) engine. In this work, n-hexadecane was used to characterize diesel and the methane/ethane/propane mixture was used to characterize NG, and a simplified diesel/NG mechanism containing 645 reactions and 155 species was established. We used brute force sensitivity analysis to optimize the key dynamic parameters of the mechanism and, through the laminar flame velocity, the substance concentration in the jet-stirred reactors and the ignition delay in the shock tube to verify the optimized n-hexadecane/NG mechanism and found that this mechanism can better respond to diesel/NG. Finally, the mechanism was coupled with the computational fluid dynamic (CFD) to study the effect of different diesel injection timings (DITs) on the combustion performance of RCCI engines. The results show that as the DIT advanced, the temperature distribution in the cylinder became uneven. Also, when the temperature was lower, the content of unburned methane in the cylinder increased. When the DIT was 45° crank angle (CA) before the top dead center (BTDC), the temperature and equivalent in the cylinder were more evenly distributed than in the cylinder and the unburned methane content was lower and diesel/NG exhibited a better combustion effect. The diesel/natural gas mechanism model can be better applied to the CFD simulation of dual-fuel RCCI engines.

1. Introduction

In view of the increasing concerns regarding the environment and the accompanying vehicle emission regulations, the development of clean alternative fuels has gained significant interest.1 Among alternative fuels, natural gas (NG) is widely favored because of its rich reserves, high octane number, and clean combustion and is regarded as one of the most potential alternatives to diesel.2−4

NOx and soot are the main emissions of diesel engines, and they have a trade-off relationship.5 To solve the trade-off relationship between NOx and soot of a conventional diesel engine, researchers have proposed a variety of advanced combustion modes, such as homogeneous charge compression ignition (HCCI),6 premixed charge compression ignition (PCCI),7,8 partially premixed compression ignition (PPCI),9 and reactivity-controlled compression ignition (RCCI).10,11 RCCI controls the combustion rate by controlling the proportion of two fuels with different activities. Diesel has a high cetane number and strong reaction activity, while NG has a high octane number and low reaction activity. Therefore, the diesel/NG dual-fuel (DF) model has great potential to develop into an RCCI combustion engine.

During the intake stroke, NG is injected into the intake port, quickly mixed with air, and then drawn into the cylinder. Diesel is injected into the cylinder as the piston approaches the top dead center (TDC).12 The diesel ignites due to the high temperature and pressure in the cylinder, which then ignites NG. The diesel self-ignites after the first ignition delay (ID) period, and the ratio of NG and air determines the second ID period.13,14

Researchers have conducted extensive studies on NG/diesel DF engines.15−20 Abdelaal et al.15 used diesel as a pilot fuel and studied the effects of exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) on DF engine emissions and performance. They found that EGR can reduce the total hydrocarbon (THC) emission at a medium load while improving engine thermal efficiency. To reduce the emissions of unburned THC and CO, diesel quantity can be increased to increase the mixture density at low loads, so as to improve the thermal efficiency.16 Papagiannakis et al.17 pointed out that the air–fuel ratio would decrease with the increase in NG substitution rate, which would reduce the effective thermal efficiency. This phenomenon was not observed at high loads; however, it was significant at medium and low loads. Bari et al.18 experimentally explored the effects of different NG substitution rates on the combustion and emission of DF engines. They found that the combustion quality of NG determines the performance of a DF engine. Engine knock occurs when the NG substitution rate is above 80%. When the diesel consumption is 60%, the economy of the DF engine was found to be the highest. Kalsi et al.19 investigated the emission characteristics of NG/diesel DF engines at different EGR rates. The results showed that the NOx emission of a DF engine decreases significantly when EGR and RCCI technology are combined, and the CO and THC emissions begin to decrease when the EGR rate is 8%. The soot emission of the engine increased slightly with the increase in EGR rate; however, its emission was still lower than that of a traditional diesel engine. Research carried out by Lim et al.20 indicated that with the increase in the NG substitution rate, CO2 and particular matter (PM) emissions decrease, THC and NOx emissions increase gradually, and the THC emission is significantly higher than that of the original diesel engine. Wang et al.21 indicated that advancing the injection time of diesel could make different changes in NG/diesel DF engines, and the highest heat release rate (HRR) could be obtained when the injection time was 42.5 °C before the top dead center (BTDC).

However, experimental research is extremely expensive, and variations in various components and concentrations in the in-cylinder combustion process cannot be clearly understood only through experiments. In recent years, with the popularization of computers, there have been significant developments in research on engine emission and performance using numerical simulations. Through the coupling of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software and mechanism, the combustion and emission mechanism of a diesel/NG DF RCCI engine can be understood in great detail.

Aggarwal et al.22 used a closed homogeneous reactor to examine the ignition characteristics of methane/n-heptane in an HCCI engine. The Chalmers mechanism,23 containing 42 species and 168 reactions, was used for the simulation. The results showed that the simulated values of ID for n-heptane and methane were consistent with the test values. However, they did not provide any experimental verification of the NG/diesel DF HCCI engine. Li et al.24 coupled a reduced primary reference fuel (PRF) mechanism with the CFD tool Converge to assess the combustion performance of the DF engine and predict the distribution of methane in the cylinder. However, they only used n-heptane as a surrogate for diesel and methane as a surrogate for NG. Poorghasemi et al.25 used a NG/diesel detailed mechanism coupled with Converge to assess the combustion performance of a DF engine under different diesel injection strategies. However, they did not verify the emission characteristics at different conditions. Hockett et al.26 simplified the detailed mechanism using the direct relation graph (DRG) simplified method and constructed a NG/diesel DF reduced mechanism that contained 141 species and 709 reactions. Further, they coupled the simplified mechanism with Converge to verify the performance and emission characteristics under the corresponding operating conditions of the engine. However, they did not verify the laminar flame velocity of the NG/air mixture and used the n-heptane representative of diesel. Zhao et al.13 used several simplified methods to build a NG/diesel DF mechanism, which contained 61 species and 199 reactions. They coupled the simplified mechanism with KIVA-4 to explore the performance and emission of NG/diesel DF engines under different conditions. However, they did not verify methane emissions and only used n-heptane as a surrogate for diesel and methane as a surrogate for natural gas.

A brief review of development in diesel/NG DF engines in recent years has been presented. The researchers considered n-heptane as an alternative fuel for diesel; however, macromolecular straight-chain hydrocarbons were the main components of the actual alternative fuels.27,28 Since diesel is a very complex mixture, it is unrealistic to construct a detailed mechanism containing all of the species. The n-hexadecane is an important component for measuring the cetane number of a fuel, and the carbon number of n-hexadecane is very similar to that of real diesel. In the DF RCCI combustion mode, diesel plays the role of ignition of the NG, resulting in low soot emissions. Thus, it is not necessary to use cycloalkane and aromatic hydrocarbons to predict the formation of soot precursors. In addition, the cetane number is closely related to the ignition characteristics, which play a very important role in advanced combustion mode (such as HCCI, PCCI, and RCCI). Therefore, using n-hexadecane to represent diesel is justified. In the composition of NG, the proportion of small-molecular straight-chain hydrocarbons is above 95%. Therefore, a mixture of methane, ethane, and propane is used to represent NG. The calculation efficiency can be significantly improved by ensuring accuracy through the use of the reduced mechanism. The simplified DF mechanism is coupled with CFD software, which provides an effective method for exploring the combustion and emission of a DF RCCI engine. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a diesel/NG reduced mechanism.

In this study, n-hexadecane was used to represent diesel and the mixture of propane, ethane, and methane was used to represent NG. Compared with the conversional diesel combustion, the soot produced in the DF mode is low;29 hence, soot emission is not verified in this study. The NG submechanism used in this study was the reduced mechanism of NG constructed in a previous study.30 The n-hexadecane submechanism was obtained by simplifying the detailed mechanism of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL). The simplified mechanism of n-hexadecane/NG DF was obtained by combining the two submechanisms and removing the repeated reaction of the n-hexadecane submechanism. The ID, laminar flame velocity, and species concentration were further verified. Finally, the reduced mechanism was coupled with Converge to verify the combustion and emission of the diesel/NG DF RCCI engine under different diesel injection timings (DITs) (−66 to −45° crank angle (CA) after top dead center (ATDC)). The research results can provide references for improving the natural gas/diesel mechanism and the development of RCCI engines.

2. Mechanism Construction

2.1. Base Natural Gas Mechanism

A poly oxymethylene dimethyl ether 3 (PODE3)/NG simplified mechanism, which included 650 reactions and 124 species, was developed by our research group and has been widely verified for ID, species concentration, and laminar flame velocity while optimizing the flame speed.26 The results indicated that the proposed mechanism can accurately predict the combustion performance of PODE3 and NG. As the simplified mechanism also includes the components and reactions of PODE3, the submechanism of NG was obtained by removing the components and reactions related to PODE3. In this study, the NG submechanism was used as the base mechanism.

2.2. Reduced n-Hexadecane Submechanism

In this study, the n-hexadecane submechanism was acquired by reducing the LLNL detailed mechanism (2115 species and 8157 reactions). To ensure the accuracy of the simplified mechanism, it is important to simplify the detailed mechanism at the comprehensive range of working conditions: the initial pressure was 4–12 atm, the initial temperature was 600–2000 K, and the equivalence ratio was 1.0. The important intermediate components of n-hexadecane were used as the initial retained components. The n-hexadecane submechanism was obtained using the reduced methods of the directed relation graph with error propagation (DRGEP), direct relation graph method (DRG), sensitivity analysis (SA), rate of production (ROP), and isomer lumping31 to reduce the n-hexadecane detailed mechanism. The isomer lumping of the n-hexadecane isomer groups is shown in Table 1. First, the path analysis of the mechanism was performed to determine the intermediate components that need to be retained. The DRG and DRGEP automatic reduced methods were then used to remove the components and their related reactions that were not closely related to the intermediate components. The SA and ROP were used to further simplify the mechanism. Finally, the reaction of isomers was merged by isomer lumping. Thus, the final simplified n-hexadecane mechanism with 295 reactions and 85 species was obtained.

Table 1. Lumped of n-Hexadecane Isomers.

| representative components | isomer group |

|---|---|

| C16H33 | C16H33-2, C16H33-3, C16H33-5, C16H33-6, C16H33-7, C16H33-8 |

| C16H33O2 | C16H33O2-3, C16H33O2-5, C16H33O2-7, C16H33O2-8 |

| C16OOH | C16OOH3-1, C16OOH5-3, C16OOH5-7, C16OOH7-9, C16OOH8-10 |

| C16OOHO2 | C16OOH3-1O2, C16OOH5-3O2, C16OOH7-9O2, C16OOH8-10O2 |

| C16KET | C16KET3-1, C16KET5-3, C16KET7-9, C16KET8-10 |

Figure 1 presents the main reaction paths of n-hexadecane at the pressure of 12 bar, equivalence ratio of 1, and the fuel consumption at 20%. It can be observed that in the low-temperature reaction stage, n-hexadecane underwent dehydrogenation reaction, primary oxygenation reaction, primary isomerization reaction, secondary oxygenation reaction, and secondary isomerization reaction. Eventually, ketohydroperoxide was formed and decomposed into small molecules. In the high-temperature reaction stage, β-decomposition was the dominant step, finally producing CO2.

Figure 1.

Main reaction paths under 20% consumption of n-hexadecane. Black font, 600 K; blue font, 800 K; and red font, 1200 K.

2.3. Formation of Reduced n-Hexadecane/Natural Gas Mechanism

A simplified n-hexadecane/NG mechanism with 645 elementary reactions and 155 components was obtained by combining n-hexadecane and NG submechanisms. In the combination process, the NG submechanism was used as the base mechanism, resulting in the elimination of the repeated components and reactions in the n-hexadecane submechanism. Figure 2 shows the specific steps of the merging process.

Figure 2.

Construction process of n-hexadecane/NG simplified mechanism.

During the preliminary verification of the ID of the combined mechanism, it was found that the simulated values of the ID period for NG are in good agreement with the predicted values of the detailed mechanism. However, there was a significant difference between the simulated and experimental data of the ID for n-hexadecane. Therefore, the combination mechanism was optimized. The brute force SA of n-hexadecane was performed at temperatures of 600, 800, and 1200 K, pressure of 12 bars, and an equivalence ratio of 1. The sensitivity coefficient was calculated using eq 1(32)

| 1 |

where τ0.5 is the ID after the rate constant divided by 2 and τ2 is the ID after the rate constant multiplied by 2. The negative sensitivity coefficient represents the promotion of the reaction, and the positive sensitivity coefficient represents the inhibition of the reaction.

Figure 3 presents the normalized results of the sensitivity coefficient of n-hexadecane to ID at high temperature (1200 K), negative temperature coefficient (NTC) region (800 K), and low temperature (600 K). By optimizing the rate constant of the reaction with high sensitivity to temperature (see Table 2), the calculated data of ID of the optimized mechanism was found to be consistent with the test data.

Figure 3.

Sensitivity coefficient of the reaction of n-hexadecane at different temperatures under an equivalence ratio of 1.0 and pressure of 12 bar.

Table 2. Optimized Reaction and Adjustment of the Pre-Exponential Factor.

| no | reaction | mechanisms | A | n | Ea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R95 | NC16H34 + OH → C16H33-1 + H2O | M-1 | 1.05 × 1010 | 0.97 | 1.59 × 103 |

| M-2 | 6.05 × 1010 | 0.97 | 1.59 × 103 | ||

| R208 | C16H33O2 → C16OOH | M-1 | 1.25 × 1011 | 0.0 | 2.085 × 104 |

| M-2 | 9.25 × 1010 | 0.0 | 2.085 × 104 | ||

| R227 | C16KET → OH + C6H13COCH2 + NC7H15CHO | M-1 | 1.05 × 1016 | 0.0 | 4.16 × 104 |

| M-2 | 1.05 × 1015 | 0.0 | 4.16 × 104 | ||

| R96 | NC16H34 + OH → C16H33 + H2O | M-1 | 5.64 × 108 | 1.61 | –3.5 × 101 |

| M-2 | 7.0 × 108 | 1.61 | –3.5 × 101 | ||

| R211 | C16OOH → C16O + OH | M-1 | 9.375 × 109 | 0.0 | 7.0 × 103 |

| M-2 | 9.375 × 108 | 0.0 | 7.0 × 103 |

As shown in Figure 3, temperature had the strongest promoting effect on the reaction C16H33O2 → C16OOH (R208) in the NTC and the low-temperature regions; in the high-temperature reaction region, temperature had a strong promoting effect on the reaction of NC16H34 + OH → C16H33-1 + H2O (R95) but had the greatest inhibitory effect on the reaction of NC16H34 + OH → C16H33 + H2O (R96). Therefore, there is a competitive relationship between R95 and R96 at high temperatures. In addition, the reaction C16OOH → C16O + OH (R211) had a sensitivity coefficient only in the low-temperature and NTC regions, which indicates that R211 only occurs at medium and low temperatures. The reaction C16KET → OH + C6H13COCH2 + NC7H15CHO (R227) had a negative sensitivity coefficient at low temperatures and a positive sensitivity coefficient in the NTC region.

To sum up, by optimizing the rate constant of the reaction with a large sensitivity coefficient, the accuracy of the mechanism for predicting the ID was improved. Table 2 provides the optimization results. The thermal physical parameters and transport parameters of the detailed mechanism were applied to the reduced mechanism. The n-hexadecane/NG reduced mechanism can be found in the Supporting Information.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation of Ignition Delay

The ID period is the critical parameter of engine ignition; therefore, it is crucial to verify the ID for engine operations. In this study, the ID period was defined as the time required for the initial temperature to increase by 400 K.33 It was assumed that the ID occurred under the conditions of homogenization, constant volume, and insulation and was calculated using the closed homogeneous reactor code.34 The simulated results were compared with the measured values.

Figure 4 presents a comparison between the simulated values and the test values of the ID for n-hexadecane at pressure values of 4 and 12 bar and equivalence ratio of 1. As can be observed, at 4 bar, the calculated results of the simplified mechanism were consistent with the simulated data of the detailed mechanism, while at 12 bar, the calculated results of the reduced mechanism were consistent with the test values. The NTC phenomenon could also be reproduced accurately.

Figure 4.

Comparison between experimental values and simulated data of ID for n-hexadecane under the pressures of 435 and 12 bar.36 Symbols: experimental data. Dash lines: reduced mechanism-simulated result. Solid lines: detailed mechanism-predicted result.

Figure 5 provides a comparison between the predicted data of the simplified mechanism and the calculated results of the detailed mechanism37 for NG at different pressure and equivalence ratios. The value of 70/20/10 represents 70, 20, and 10% of CH4, C2H6, and C3H8, respectively. The ratio of 90/6.7/3.3 represents 90, 6.7, and 3.3% of CH4, C2H6, and C3H8, respectively, in NG. As could be seen, the simulated results of the simplified mechanism were in good agreement with the predicted results of the detailed mechanism. Therefore, the simplified mechanism of n-hexadecane/NG can accurately predict the ID of n-hexadecane and NG.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the predicted values of the ID of the simplified mechanism and the simulated results of the detailed mechanism: (a–f). Dash lines: reduced mechanism; solid lines: detailed NG mechanism (NUIG).37

3.2. Validation of Species Concentration

The species concentration plays a critical role in predicting the intermediate and final products. To evaluate the accuracy of the current simplified mechanism, the species concentration must be verified. The curves of reactants, important intermediate products, and products of n-hexadecane at high temperatures were measured by Ristori et al.38 in a jet-stirred reactor (JSR).

The simulation was carried out using the perfectly stirred reactor (PSR) code,34 and it was assumed that the reaction occurs under homogenized and isothermic conditions. The experimental temperature (1000–1250 K), pressure (P = 1 bar), equivalence ratio (Φ = 1), and residence time (τ = 70 mss) of Ristori et al.38 were used as initial conditions for the calculation.

Figure 6 provides a comparison of the calculated and test data of the species concentration for n-hexadecane. As can be seen from Figure 6, the calculated results were in good agreement with the measured values, although there was a slight deviation. This is because the prediction of species concentration was related to the small molecules in the mechanism. The combination of NG submechanism and n-hexadecane submechanism increases the number of small molecules, thus affecting the reaction rate of n-hexadecane cracking into small molecules. Therefore, there will be some errors in calculating the species concentration of n-hexadecane. Nevertheless, the reduced mechanism can accurately predict species concentration of important intermediate components, reactants, and production of n-hexadecane.

Figure 6.

Comparison between the test38 and predicted values of component concentrations for n-hexadecane. Solid lines: reduced mechanism-simulated results. Symbols: test values.

3.3. Validation of Laminar Flame Speed

Laminar flame speed is also a critical combustion parameter, which can represent the chemical and physical properties of fuel and oxidant in the process of mixing. Hence, it was also verified in this study. The laminar flame velocities were calculated using the PREMIX code.34

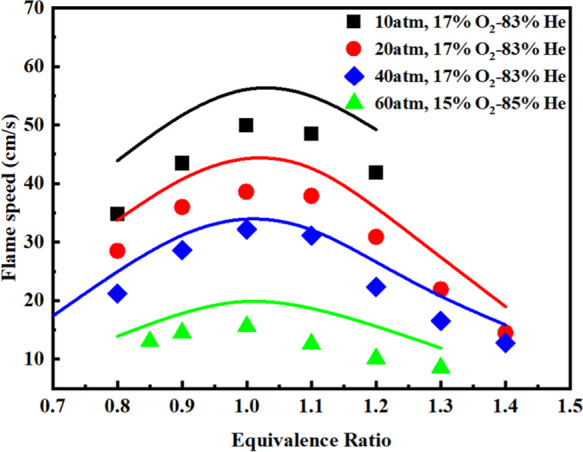

Li et al.39 obtained the test values of the laminar flame speed for n-hexadecane/air mixture at the unburned gas temperature (443 K), the atmospheric pressure, and a wide range of equivalence ratios (0.8 to 1.4). The laminar flame speed of methane/air was measured by Rozenchan et al.40 under the unburned gas temperature of 298 K and a wide pressure (1–20 atm) range. At the pressure range of 10–40 atm, they tested the laminar flame speed of the CH4/He/O2 mixture using an O2/He mixture with a volume ratio of 17:83 as the oxidant. At the pressure of 60 atm, they used a mixture of O2/He with the volume ratio of 15:85 as an oxidant to test the laminar flame speed of the CH4/He/O2 mixture. Based on the above test data, the laminar flame velocities of n-hexadecane/air, NG/air, and NG/oxygen/helium mixtures were verified.

Figure 7 presents a comparison between the test and simulated data of the laminar flame velocity of n-hexadecane/air at a temperature of 443 K and normal atmospheric pressure. As can be known, the flame velocities increased first and then decreased with the increase of the equivalence ratio. At a lean-burn condition (Φ < 1), the predicted data of the reduced mechanism are well in agreement with the test values. However, under rich combustion conditions (Φ > 1), there was a slight deviation between the simulated results of the simplified mechanism and the measured values. This is because the speed of flame propagation is controlled by the reactions between small molecules. During the combination of n-hexadecane and NG submechanism, the number of C0–C3 reactions increased, which influenced the rate constant of the reaction with the methane laminar flame-sensitive reaction. However, in general, the variation of laminar flame speeds of n-hexadecane/air can be accurately captured by the reduced mechanism.

Figure 7.

Comparison between experimental values39 and simulated data of laminar flame velocities for n-hexadecane. Symbols: test values. Solid lines: reduced mechanism-predicted results.

The comparison of the predicted and experimental data of the laminar flame velocity of CH4/air at an unburned gas temperature of 298 K and wide pressure (1–20 atm) conditions are shown in Figure 8. As can be observed, the flame speeds decreased with the increase of initial pressure, and the calculated results of the reduced mechanism are well in agreement with the test values under different pressures and equivalence ratios. Therefore, the current mechanism can accurately capture the variation of laminar flame velocity in CH4/air.

Figure 8.

Comparison between measured values40 and simulated data of laminar flame speeds for the methane/air mixture. Symbols: test values. Solid lines: reduced mechanism-simulated values.

Figure 9 presents a comparison between simulated data and measured values of the laminar flame speeds of CH4/O2/He at the conditions of different oxidants, pressure from 10 to 60 atm, and unburned gas temperature of 298 K. It was observed that with the increase of equivalence ratios, the laminar flame velocities increased first and then decreased, reaching a peak when the equivalence ratio was 1. Overall, the predicted results of the current mechanism are in good agreement with the test values.

Figure 9.

Comparison between the experimental and simulated values40 of laminar flame velocities for CH4/O2/He mixture with diluted helium. Solid lines: reduced mechanism-simulated results. Symbols: experimental values.

Therefore, the developed reduced mechanism can accurately capture the laminar flame velocity of n-hexadecane and NG under different pressures, equivalence ratios, and oxidant conditions.

3.4. Validation of Combustion and Emissions in Diesel/NG DF RCCI Engine

In the engine test, diesel was directly injected into the cylinder, while NG was injected into the intake port, and the mass of injected NG was controlled by the electronic control unit (ECU). The detailed experimental bench setup is shown in Figure 10, and the engine parameters are shown in Table 3. The physical and chemical properties of test fuels are shown in Table 4.

Figure 10.

Test engine device setting.

Table 3. Main Technical Parameters of the Engine.

| parameter | value |

|---|---|

| stroke (mm) | 145 |

| bore (mm) | 123 |

| compression ratio (−) | 17.5 |

| connecting rod length (mm) | 224 |

| displacement (L) | 10 |

| Nozzle hole × diameter (mm) | 8 × 0.121 |

| EVO (°CA ATDC) | 140 |

| IVC (°CA ATDC) | –156 |

Table 4. Physical and Chemical Properties of Diesel and Natural Gas41.

| property | diesel | natural gas |

|---|---|---|

| density (kg/m3) | 814 | 0.75(@0 °C and 1 atm) |

| cetane number | 44 | |

| lower heating value (MJ/kg) | 44.64 | 48.15 |

| H/C ratio | 1.90 | 3.96 |

In this study, the substitution rate was defined as in eq 2,42 and the calculation formula of the HRR of a dual-fuel engine is shown in eq 3(43)

| 2 |

where mdiesel and mNG are the mass of diesel and NG, respectively, and LHVdiesel and LHVNG are the low heat values of diesel and NG, respectively.

| 3 |

where V is defined as the instantaneous cylinder volume, γ is the specific heat ratio, and p is the measured in-cylinder pressure.

The CFD software used for the simulation was Converge v2.4.44 The working process of an internal combustion engine involves a high Reynolds number and multiphase turbulent processes, which includes turbulent flow, spray, evaporation, mixing, combustion, heat transfer, and emission generation. The RNG k--ε model developed by Han and Reitz45 was used as the turbulence model for the simulation. The KH–RT spray model46 was applied to simulate the spray crushing process. When the fuel is injected into the cylinder, it is necessary to simulate the evaporation process of the fuel droplets. To obtain the change in the drop radius caused by evaporation, the Frossling correlation47 was used to simulate the evaporation process of fuel drops. The No Time Counter model developed by Schmidt and Rutl48 was used to simulate the collision process between fuel droplets. Through the SAGE model,49 the simplified mechanism was introduced into Converge to simulate the combustion process of the diesel/NG DF RCCI engine. The soot precursor model was not added to the current mechanism as the soot emissions from the diesel/NG DF engine are extremely low.29 The physical models used in the simulation process are shown in Table 5. The experimental conditions are shown in Table 6.

Table 5. Submodels Used in the Simulation.

| chemical mechanism | n-hexadecane/NG reduced mechanism | |

|---|---|---|

| turbulent model | RANS (RNG k-ε)45 | |

| spray model | wall interaction model | wall film51 |

| collision model | no time counter48 | |

| vaporization model | Frossling correlation47 | |

| breakup model | KH–RT46 | |

| drop drag model | dynamic drag50 | |

| combustion model | SAGE Multizone49 | |

| NOx model | extended Zeldovich mechanism52 | |

Table 6. Experimental Conditions.

| parameter | value |

|---|---|

| diesel injection timing (°CA ATDC) | –45, −55, −66 |

| EGR rate (%) | 0 |

| diesel injection pressure (MPa) | 100 |

| mass of injection diesel (mg/cyc) | 7.2 |

| speed (rpm) | 1220 |

| substitution rate (%) | 90 |

| BMEP (MPa) | 1 |

As the injector had eight injection holes, the one-eighth model was used for simulation (see Figure 11). The calculation started from the intake valve closure (IVC) timing (−156° CA ATDC) to the exhaust valve open (EVO) timing (140° CA ATDC). The base grid was set to 2 mm and the adaptive mesh refinement (AMR) scale was set to 3, resulting in a minimum grid size of 0.25 mm. The subgrid criterion for velocity and temperature was set as 2 m/s and 5 K, respectively. Fixed embedding was performed on piston, liner, head, and injector. The fixed embedding scale of piston, liner, and head was 1, i.e., the fixed embedding grid size was 1 mm. The fixed embedding scale of the injector was set as 2, corresponding to the fixed embedding grid size of 0.5 mm.

Figure 11.

Computational meshes of in-cylinder temperature distribution at TDC.

Figure 12 presents a comparison between the test data and the calculated results of injection pressure (IPs) and HRR under different DIT conditions. It can be observed that the simulated results of IPs were well in agreement with the test values; however, those of HRR showed some deviation. On the one hand, in the simulation, the HRR was equal to the difference between the heat transfer of the chemical kinetic model and the heat transfer of the cylinder wall. In the experiment, the HRR was derived by the average pressure, and the average pressure was obtained based on the assumption that the in-cylinder pressure and the temperature were uniformly distributed. As the local high-temperature region in the cylinder was ignored, the experimental values of HRR were lower than the predicted values of the current mechanism. On the other hand, there is a deviation between the fuel injection duration and the fuel injection rule used in the simulation and the experimental value. Nevertheless, the simulation results still accurately captured the tendency of the HRR, which indicated that the constructed reduced model can be used to predict the in-cylinder combustion of the actual diesel/NG DF RCCI engine.

Figure 12.

Comparison between calculated values and test data of heat release rate (hrr) and in-cylinder pressures (IPs): (a) −45, (b) −55, and (c) −66.

With the advance of DIT, the combustible mixture is too lean (see Figure 15), and the reactivity decreases, which results in the decrease of flame propagation speed, the in-cylinder temperature decrease (see Figure 13), and the start of combustion (SOC) point delay, which are not conducive to the constant volume combustion and the cylinder pressure decrease.

Figure 15.

Isosurfaces of the equivalence ratio and temperature in the cylinder with different DITs at CA50.

Figure 13.

Distribution of the temperature in the cylinder with different DITs.

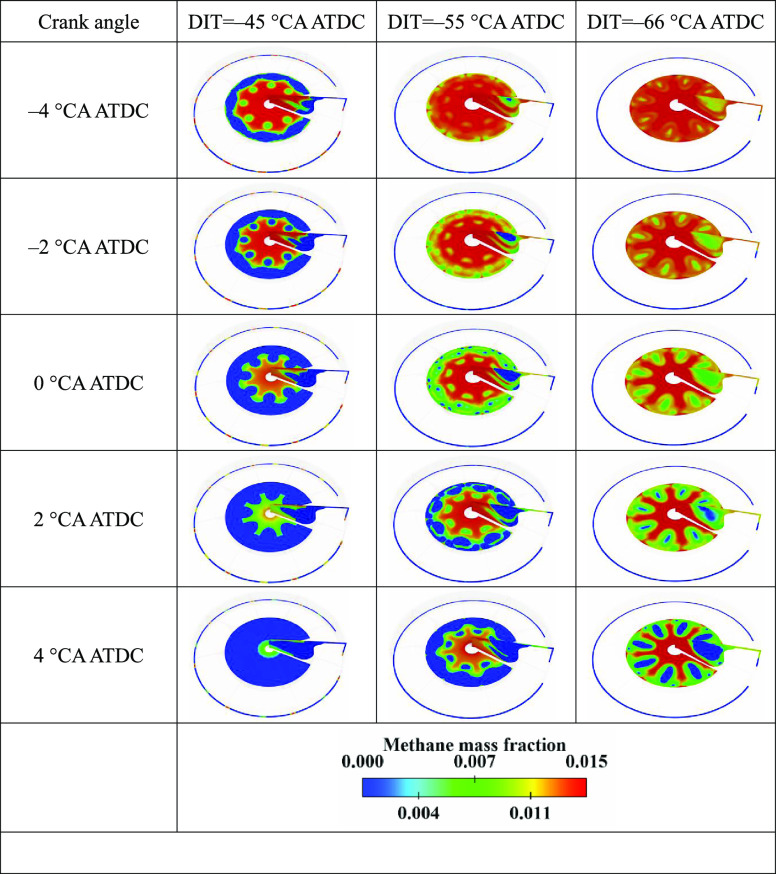

Figure 13 shows the distribution of the temperature in the cylinder with different DITs. Figure 14 shows the distribution of the unburned methane in the cylinder with different DITs. As can be seen from Figure 14, the NG present in the cylinder center was the main source of unburned methane emissions for the diesel/NG DF RCCI engine. This is because the lower reactivity of the combustible mixture in the cylinder center leads to a lower combustion temperature (see Figure 13), and the NG self-ignition temperature was high. Hence, the NG in the cylinder center could not be ignited. Therefore, this part of the NG was discharged out of the cylinder with the exhaust gas.

Figure 14.

Distribution of the unburned methane in the cylinder with different DITs.

Figure 15 shows the isosurfaces of equivalence ratio and temperature in the cylinder with different DITs at CA50. As can be seen from Figures 14 and 15, in the region with an equivalence ratio of 0.5, although the combustion temperature was not the highest (see Figure 15), it was the area that consumes the most NG (see Figure 14). Therefore, when the equivalence ratio is in the range of 0.5–0.7, the activity of the combustible mixture is the highest. Furthermore, with the DIT delay, the highest temperature appeared at the head of the combustion chamber, indicating that NOx were more easily generated at the cylinder head.

With the DIT delay, the stratification of the mixture in a cylinder was obvious, the SOC was advanced, and the combustion was close to constant volume combustion, which promotes NG combustion and increases thermal efficiency.

4. Conclusions

In this study, diesel was represented by n-hexadecane and NG was represented by a mixture of CH4, C2H6, and C3H8. The submechanism of n-hexadecane was optimized using the brute force SA. Therefore, a diesel/NG simplified mechanism with 155 components and 645 reactions was constructed for a DF RCCI engine.

-

1.

The simulated data of the optimized simplified mechanism for ID were well agreement with the test data, and the negative temperature coefficient phenomenon of n-hexadecane could be reproduced. The ignition delay of the NG predicted by the simplified mechanism was consistent with the predicted values of the detailed mechanism.

-

2.

When the component concentration was verified. It was found that the predicted values of the component concentrations for the current mechanism were consistent with the measured values.

-

3.

The laminar flame velocities of methane/air and methane/argon/oxygen mixture were verified under different pressures (10–60 atm), and the current mechanism accurately captured the laminar flame velocities of NG.

-

4.

The current mechanism was coupled with Converge to verify the performance and emission characteristics of the diesel/NG DF RCCI engine at different DITs. The predicted values were consistent with the measured data.

-

5.

The simplified mechanism of n-hexadecane/NG can be used to simulate the in-cylinder combustion characteristics and emission generation of diesel/NG DF RCCI engines.

Acknowledgments

The research is sponsored by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Development and Integration on Hybrid Powertrain System of Cost-effective Commercial Vehicle, No. 2018YFB0105900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51966001) and the Scientific Research and Technology Development Program of Guangxi (1598007-44).

Glossary

Nomenclature Used

- AMR

adaptive mesh refinement

- ATDC

after top dead center

- CA

crank angle

- CA50

crank angle location for 50% cumulative heat release

- CFD

computational fluid dynamic

- CH4

methane

- C2H6

ethane

- C3H8

propane

- CO

carbon oxide

- DF

dual fuel

- DIT

diesel injection timing

- DRG

direct relation graph

- DRGEP

directed relation graph with error propagation

- EGR

exhaust gas recirculation

- EVO

exhaust valve open

- HCCI

homogeneous charge compression ignition

- He

helium

- HRR

heat release rate

- ID

ignition delay

- ICP

in-cylinder pressure

- IP

injection pressure

- IVC

intake valve closure

- JSR

jet-stirred reactor

- NG

natural gas

- NOx

nitrogen oxide

- NTC

negative temperature coefficient

- O2

oxygen

- PCCI

premixed charge compression ignition

- PM

particular matter

- PODE3

poly oxymethylene dimethyl ether 3

- PPCI

partially premixed compression ignition

- PSR

perfectly stirred reactor

- RCCI

reactivity-controlled compression ignition

- SA

sensitivity analysis

- THC

total hydrocarbon

- BTDC

before top dead center

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c02514.

Thermodynamic; transport; and mechanism data files of the 645 reactions and 155 species set in CHEMKIN format (ZIP)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Liang Y.; Bian X.; Qian W.; Pan M.; Ban Z.; Yu Z. Theoretical analysis of a regenerative supercritical carbon dioxide Brayton cycle/organic Rankine cycle dual loop for waste heat recovery of a diesel/natural gas dual-fuel engine. Energy Convers. Manage. 2019, 197, 111845 10.1016/j.enconman.2019.111845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Liu X.; Liu H.; Ye Y.; Wang H.; Dong J.; Liu B.; Yao M. Kinetic Study of the Ignition Process of Methane/n-Heptane Fuel Blends under High-Pressure Direct-Injection Natural Gas Engine Conditions. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 14796–14813. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c02667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Geng P. A review on natural gas/diesel dual fuel combustion, emissions and performance. Fuel Process Technol. 2016, 142, 264–278. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2015.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A.; Panua R. S.; Debroy D.; Bose P. K. An experimental study of the performance, combustion and emission characteristics of a CI engine under dual fuel mode using CNG and oxygenated pilot fuel blends. Energy 2015, 86, 560–573. 10.1016/j.energy.2015.04.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; He J.; Chen Z.; Geng L. A comparative study of combustion and emission characteristics of dual-fuel engine fueled with diesel/methanol and diesel–polyoxymethylene dimethyl ether blend/methanol. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 147, 714–722. 10.1016/j.psep.2021.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taghavi M.; Gharehghani A.; Nejad F. B.; Mirsalim M. Developing a model to predict the start of combustion in HCCI engine using ANN-GA approach. Energy Convers. Manage. 2019, 195, 57–69. 10.1016/j.enconman.2019.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salahi M. M.; Gharehghani A. Control of combustion phasing and operating range extension of natural gas PCCI engines using ozone species. Energy Convers. Manage. 2019, 199, 112000 10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Ma S.; Zhang Z.; Zheng Z.; Yao M. Study of the control strategies on soot reduction under early-injection conditions on a diesel engine. Fuel 2015, 139, 472–481. 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.; Shuai S.; Wang Z.; Wang J.; Xu H. New premixed compression ignition concept for direct injection IC engines fueled with straight-run naphtha. Energy Convers. Manage. 2013, 68, 161–168. 10.1016/j.enconman.2013.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz R. D.; Duraisamy G. Review of high efficiency and clean reactivity controlled compression ignition (RCCI) combustion in internal combustion engines. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2015, 46, 12–71. 10.1016/j.pecs.2014.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Tang Q.; Yang Z.; Ran X.; Geng C.; Chen B.; Feng L.; Yao M. A comparative study on partially premixed combustion (PPC) and reactivity controlled compression ignition (RCCI) in an optical engine. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2019, 37, 4759–4766. 10.1016/j.proci.2018.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; He J.; Zhong X. Engine combustion and emission fuelled with natural gas: a review. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 1123–1136. 10.1016/j.joei.2018.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W.; Yang W.; Fan L.; Zhou D.; Ma X. Development of a skeletal mechanism for heavy-duty engines fuelled by diesel and natural gas. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 123, 1060–1071. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.05.175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abagnale C.; Cameretti M. C.; Simio L. D.; Gambino M.; Iannaccone S.; Tuccillo R. Numerical simulation and experimental test of dual fuel operated diesel engines. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 65, 403–417. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.01.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelaal M. M.; Hegab A. H. Combustion and emission characteristics of a natural gas-fueled diesel engine with EGR. Energy Convers. Manage. 2012, 64, 301–312. 10.1016/j.enconman.2012.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci A. P.; Risi A. D.; Laforgia D.; Naccarato F. Experimental investigation and combustion analysis of a direct injection dual-fuel diesel-natural gas engine. Energy 2008, 33, 256–263. 10.1016/j.energy.2007.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papagiannakis R. G.; Kotsiopoulos P. N.; Zannis T. C.; Yfantis E. A.; Hountalas D. T.; Rakopoulos C. D. Theoretical study of the effects of engine parameters on performance and emissions of a pilot ignited natural gas diesel engine. Energy 2010, 35, 1129–1138. 10.1016/j.energy.2009.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bari S.; Hossain S. N. Performance of a diesel engine run on diesel and natural gas in dual-fuel mode of operation. Energy Procedia 2019, 160, 215–222. 10.1016/j.egypro.2019.02.139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsi S. S.; Subramanian K. A. Experimental investigations of effects of EGR on performance and emissions characteristics of CNG fueled reactivity controlled compression ignition (RCCI) engine. Energy Convers. Manage. 2016, 130, 91–105. 10.1016/j.enconman.2016.10.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim O.; Iida N.; Cho G.; Narankhuu J. In The Research About Engine Optimization And Emission Characteristic Of Dual Fuel Engine Fueled with Natural Gas And Diesel, SAE Technical Paper, 2012-32-0008, SAE, 2012.

- Wang Z.; Zhao Z.; Wang D.; Tan M.; Han Y.; Liu Z.; Dou H. Impact of pilot diesel ignition mode on combustion and emissions characteristics of a diesel/natural gas dual fuel heavy-duty engine. Fuel 2016, 167, 248–256. 10.1016/j.fuel.2015.11.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal S. K.; Awomolo O.; Akber K. Ignition characteristics of heptane-hydrogen and heptane-methane fuel blends at elevated pressures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 15392–15402. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.08.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golovitchev V. I.Mechanisms (Combustion Chemistry). http://www.tfd.chalmers.se/~valeri/MECH.html.

- Li Y.; Li H.; Guo H.; Li Y.; Yao M. A numerical investigation on methane combustion and emissions from a natural gas-diesel dual fuel engine using CFD model. Appl. Energy 2017, 205, 153–162. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.07.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poorghasemi K.; Saray R. K.; Ansari E.; Irdmousa B. K.; Shahbakhti M.; Naber J. D. Effect of diesel injection strategies on natural gas/diesel RCCI combustion characteristics in a light duty diesel engine. Appl. Energy 2017, 199, 430–446. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hockett A.; Hampson G.; Marchese A. J. Development and Validation of a Reduced Chemical Kinetic Mechanism for CFD Simulations of Natural Gas/Diesel Dual Fuel Engines. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 2414–2427. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.5b02655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitz W. J.; Mueller C. J. Recent progress in the development of diesel surrogate fuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2011, 37, 330–350. 10.1016/j.pecs.2010.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.; Ming J.; Liu Y.; Li Y.; Xie M.; Yin H. Application of a Decoupling Methodology for Development of Skeletal Oxidation Mechanisms for Heavy n-Alkanes from n-Octane to n-Hexadecane. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 3467–3479. 10.1021/ef400460d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Zhu Z.; Chen Y.; Chen Y.; Lv D.; Zhu J.; Ou Yang T. Experimental and numerical study of multiple injection effects on combustion and emission characteristics of natural gas-diesel dual-fuel engine. Energy Convers. Manage. 2019, 183, 84–96. 10.1016/j.enconman.2018.12.110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Chen Y.; Zhu J.; Chen Y.; Lv D.; Zhu Z.; Wei L.; Wei Y. Construction of a Reduced PODE3/Nature Gas Dual-Fuel Mechanism under Enginelike Conditions. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 3504–3517. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b03926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An H.; Yang W.; Maghbouli A.; Li J.; Chua K. A skeletal mechanism for biodiesel blend surrogates combustion. Energy Convers. Manage. 2014, 81, 51–59. 10.1016/j.enconman.2014.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Zhu J.; Lv D.; Wei Y.; Zhu Z.; Yu B.; Chen Y. Development of a reduced n-heptane-n-butylbenzene-polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) mechanism for engine combustion simulation and soot prediction. Energy 2018, 165, 90–105. 10.1016/j.energy.2018.09.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ra Y.; Reitz R. D. A reduced chemical kinetic model for IC engine combustion simulations with primary reference fuels. Combust. Flame 2008, 155, 713–738. 10.1016/j.combustflame.2008.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kee R. J.; Rupley F. M.; Miller J. A.. Chemkin-II: A Fortran Chemical Kinetics Package For The Analysis Of Gas-phase Chemical Kinetics, Sandia National Labs., Livermore, 1989.

- Vasu S. S.; Davidson D. F.; Hong Z.; Vasudevan V.; Hanson R. K. n-Dodecane oxidation at high-pressures: Measurements of ignition delay times and OH concentration time-histories. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2009, 32, 173–180. 10.1016/j.proci.2008.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Liang X.; Yu H.; Wang Y.; Zhu Z. Comparison the Performance of N-heptane, N-dodecane, N-tetradecane and N-hexadecane. Energy Procedia 2017, 105, 1426–1433. 10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Healy D.; Kalitan D. M.; Aul C. J.; Petersen E. L.; Curran H. J.; Bourque G. Oxidation of C1–C5 Alkane Quinternary Natural Gas Mixtures at High Pressures. Energy Fuels 2010, 24, 1521–1528. 10.1021/ef9011005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ristori A.; Dagaut P.; Cathonnet M. The oxidation of n-Hexadecane: experimental and detailed kinetic modeling. Combust. Flame 2001, 125, 1128–1137. 10.1016/S0010-2180(01)00232-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.; Liu N.; Zhao R.; Zhang H.; Egolfopoulos F. Flame propagation of mixtures of air with high molecular weight neat hydrocarbons and practical jet and diesel fuels. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2013, 34, 727–733. 10.1016/j.proci.2012.05.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenchan G.; Zhu D. L.; Law C. K.; Tse S. D. Outward propagation, burning velocities, and chemical effects of methane flames up to 60 ATM. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2002, 29, 1461–1470. 10.1016/S1540-7489(02)80179-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi A.; Guo H.; Birouk M. Split diesel injection effect on knocking of natural gas/diesel dual-fuel engine at high load conditions. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115828 10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W.; Park C.; Bae C. Characterization of combustion process and emissions in a natural gas/diesel dual-fuel compression-ignition engine. Fuel 2021, 291, 120043 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.120043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Teng W.; Li Z.; Liu Q.; Wang Q.; Pan M. Improvement of emission characteristics and maximum pressure rise rate of diesel engines fueled with n-butanol/PODE3-4/diesel blends at high injection pressure. Energy Convers. Manage. 2017, 152, 45–56. 10.1016/j.enconman.2017.09.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards K. J. SAP.Converge Manual. Converg (Version 24) Manual; Converg Sci Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Han Z.; Reitz R. D. Turbulence Modeling of Internal Combustion Engines Using RNG k-ε Models. Combust. Sci. Technol. 1995, 106, 267–295. 10.1080/00102209508907782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beale J. C.; Reitz R. D. Modeling Spray Atomization with the Kelvin-Helmholtz/Rayleigh Taylor Hybrid Model. Atomization Sprays 1999, 9, 623–650. 10.1615/AtomizSpr.v9.i6.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amsden A. A.; O’rourke P. J.; Butler T. D.. KIVA-II: A Computer Program For Chemically Reactive Flows With Sprays; Los Alamos National Lab, Los Alamos, NM, 1989.

- Schmidt D. P.; Rutland C. J. A new droplet collision algorithm. J. Comput. Phys. 2000, 164, 62–80. 10.1006/jcph.2000.6568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senecal P. K.; Pomraning E.; Richards K. J.; Briggs T. E.; Choi C. Y.; McDavid R. M.; Patterson M. A.. Multi-Dimensional Modeling of Direct-Injection Diesel Spray Liquid Length and Flame Lift-off Length Using CFD and Parallel Detailed Chemistry, SAE Technical Paper, 2003-01-1043, SAE, 2003.

- Liu A. B.; Mather D.; Reitz R. D.. Modeling the Effects Of Drop Drag And Breakup On Fuel Sprays, SAE Technical Paper, 930072, SAE, 1993.

- O’Rourke P. J.; Amsden A. A.. A Spray/Wall Interaction Submodel for the KIVA-3 Wall Film Model, SAE Technical Paper, 2000-01-0271, SAE, 2000.

- Tao F.; Golovitchev V. I.; Chomiak J.. Self-Ignition and Early Combustion Process of N-heptane Sprays Under Diluted Air Conditions: Numerical Studies Based on Detailed Chemistry, SAE Technical Paper 2000-01-2931, SAE, 2000.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.