Abstract

Muscle microvasculature critically regulates skeletal and cardiac muscle health and function. It provides endothelial surface area for substrate exchange between the plasma compartment and the muscle interstitium. Insulin fine-tunes muscle microvascular perfusion to regulate its own action in muscle and oxygen and nutrient supplies to muscle. Specifically, insulin increases muscle microvascular perfusion, which results in increased delivery of insulin to the capillaries that bathe the muscle cells and then facilitate its own transendothelial transport to reach the muscle interstitium. In type 2 diabetes, muscle microvascular responses to insulin are blunted and there is capillary rarefaction. Both loss of capillary density and decreased insulin-mediated capillary recruitment contribute to a decreased endothelial surface area available for substrate exchange. Vasculature expresses abundant glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptors. GLP-1, in addition to its well-characterized glycemic actions, improves endothelial function, increases muscle microvascular perfusion, and stimulates angiogenesis. Importantly, these actions are preserved in the insulin resistant states. Thus, treatment of insulin resistant patients with GLP-1 receptor agonists may improve skeletal and cardiac muscle microvascular perfusion and increase muscle capillarization, leading to improved delivery of oxygen, nutrients, and hormones such as insulin to the myocytes. These actions of GLP-1 impact skeletal and cardiac muscle function and systems biology such as functional exercise capacity. Preclinical studies and clinical trials involving the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists have shown salutary cardiovascular effects and improved cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Future studies should further examine the different roles of GLP-1 in cardiac as well as skeletal muscle function.

Keywords: cardiac muscle, endothelium, GLP-1, insulin resistance, microvascular perfusion, skeletal muscle

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Insulin resistance is common in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which predisposes people who have it to metabolic derangements and accelerated cardiovascular complications. People with insulin resistance manifest impaired insulin action in all insulin target organs/tissues including skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, liver, adipose tissue, and brain, as well as the vasculature. Both endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells express abundant insulin receptors, insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) receptors, and the insulin and IGF-I hybrid receptors. Insulin acts via these receptors to regulate vascular tone and tissue perfusion. Muscle microvasculature provides an endothelial surface to facilitate tissue extraction of oxygen, nutrients, and hormones and the removal of tissue metabolic wastes and by-products. Insulin actively regulates muscle microvascular perfusion, and this action is blunted in humans and animal models with evidence of metabolic insulin resistance. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), a hormone secreted by intestinal L-cells in response to nutrient intake, stimulates glucose-dependent secretion of insulin, decreases glucagon, and suppresses appetite and thus regulates blood glucose levels, particularly postprandially. As such, GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists have become a major therapeutic option for the management of hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes. GLP-1 is also a vasoactive hormone, and it acts via the GLP-1R to cause vasodilation of both resistance vessels and the microvasculature to regulate tissue perfusion. Multiple clinical trials have demonstrated a beneficial cardiovascular action of GLP-1R agonists in patients with T2DM. Here we review the regulation of skeletal and cardiac muscle microvascular perfusion by insulin and GLP-1, their interplay in health and T2DM, and the clinical implications of these actions.

2 |. MUSCLE MICROVASCULATURE CRITICALLY REGULATES MUSCLE HEALTH AND INSULIN ACTION

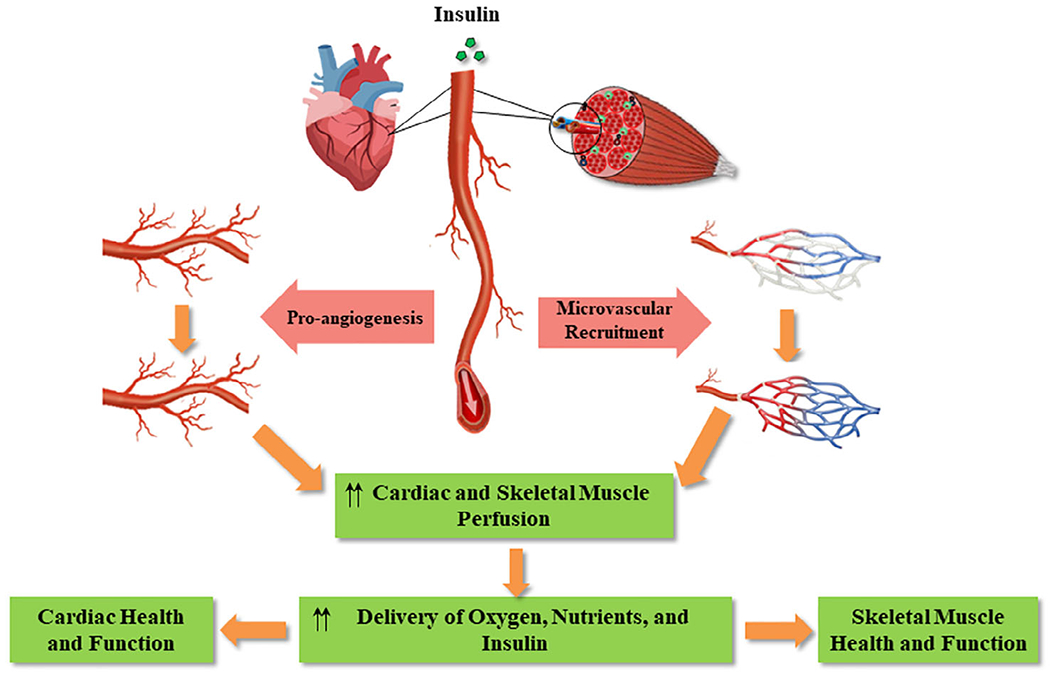

Muscle microvasculature is composed of small arterioles, capillaries, and small venules. It plays a critical role in the maintenance of muscle health and function by allowing the extraction of nutrients, oxygen, and hormones such as insulin from the blood into the muscle interstitium and the removal of metabolic by-products from the muscle cells to the circulation with subsequent clearance by the liver and kidney (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Muscle microvasculature regulates tissue perfusion, health, and function

Skeletal muscle is a major target of insulin actions and responsible for ~80% of insulin-mediated glucose uptake.1,2 Numerous human and rodent studies have convincingly demonstrated that the skeletal muscle microvasculature is an important site for insulin action as well as a rate-limiting regulator of insulin action.3,4 In the resting state, approximately one third of capillaries are perfused in the skeletal muscle.5 In the presence of increased metabolic demand such as occurs with exercise, more capillaries are perfused via the relaxation of the precapillary arterioles, a process termed microvascular recruitment. Increasing tissue microvascular perfusion results in an expansion of the endothelial surface area and increased substrate delivery and extraction. Given the slow blood flow (only ~0.2 L/min)6 and the sheer size of the endothelial surface area within the skeletal muscle, even small changes in microvascular perfusion profoundly affect the availability of oxygen, nutrients, and hormones to the myocytes with subsequent impact on muscle health and function.

Insulin relaxes the precapillary arterioles to increase the delivery of insulin to the capillaries nurturing the myocytes, expand the endothelial surface area available for insulin extraction from the plasma compartment, and facilitate the transendothelial transport of insulin to enter the muscle interstitium. These steps are rate-limiting for insulin action in muscle7–9 as it is the muscle interstitial insulin concentrations that correlate closely with insulin’s metabolic actions, not those of plasma.10 After systemic administration, insulin rapidly recruits muscle microvasculature to increase its perfusion. Increased perfusion occurs within 5-10 minutes, via insulin action on three different receptors in the endothelium, including insulin receptors, IGF-I receptors, and the insulin/IGF-I hybrid receptors, and this occurs well before the increase in insulin-stimulated glucose disposal (~ 20-30 minutes) in muscle. This process is nitric oxide (NO)-dependent as inhibition of NO synthesis during insulin infusion abolishes insulin-induced microvascular recruitment in muscle. Importantly, this NO-mediated vascular action of insulin could contribute up to 25-40% of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in humans11 and rodents.12,13

Similar to the skeletal muscle, the coronary microvasculature plays a dynamic role in the regulation of coronary blood flow to meet the oxygen and nutrient demand of the myocardium. Compared with other insulin sensitive tissues, the myocardium has a much larger endothelial surface area but only ~50% of myocardial capillaries are perfused at rest.14 When myocardial oxygen demand increases, myocardial blood flow velocity and/or volume are increased to meet the requirement. Insulin exerts a vasodilatory action on the coronary vasculature to increase myocardial blood flow in humans.15–19 Using myocardial contrast echocardiography (MCE), a noninvasive technology that employs perfluorocarbon gas containing microbubbles to noninvasively assess in vivo perfusion of the cardiac microvasculature,20,21 we showed that insulin potently increases cardiac microvascular perfusion in healthy humans.22–24

3 |. MUSCLE MICROVASCULAR PERFUSION IN T2DM

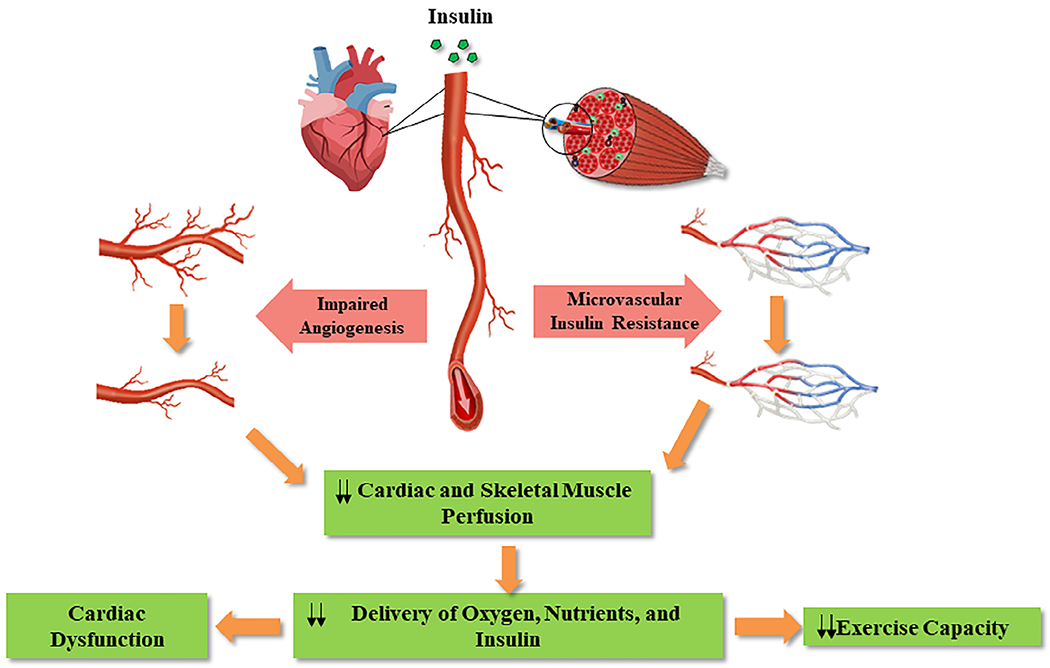

Metabolic insulin resistance is accompanied by vascular insulin resistance, which was first demonstrated in larger conduit arteries.6,25–28 Over the past decade, evidence has confirmed that vascular insulin resistance is present in the skeletal and cardiac muscle microvasculature in humans and animals with metabolic insulin resistance. Insulin-mediated microvascular recruitment is clearly impaired in the skeletal muscle of obese and diabetic animals29,30 and obese humans31 and in the cardiac muscle of humans with obesity32 or T2DM.17 This is not surprising as microvascular functions are dependent on a normal metabolic milieu, which is disturbed in the state of insulin resistance as seen in obesity and T2DM, including elevated plasma free fatty acids and inflammatory cytokines.33,34 Indeed, raising plasma concentrations of either tumor necrosis factor α or free fatty acids via systemic infusion promptly induces microvascular insulin resistance in both humans and laboratory rodents.23,24,35–37 Importantly, raising plasma insulin levels ~8-fold by ingesting a mixed meal not only fails to increase but paradoxically decreases cardiac microvascular perfusion in people with T2DM.38,39 This finding is consistent with the selective resistance in insulin action through the PI3-kinase pathway,40–42 the insulin signaling pathway required for insulin regulation of NO synthase and NO generation. In contrast, the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway remains responsive to insulin’s vasoconstrictive actions via endothelin-1 (ET-1), a potent vasoconstrictor. Selective insulin resistance alters balance between NO and ET-1 production43 and leads to increased vasoconstriction in muscle arterioles and consequent decreased tissue perfusion.44,45 The net result is a decrease of endothelial surface area available for substrate delivery and extraction. As insulin’s vascular actions contribute to its metabolic action, factors causing metabolic insulin resistance have essentially all been shown to also decrease muscle microvascular insulin responsiveness. In fact, microvascular insulin resistance occurs well before metabolic insulin resistance in rodents with diet-induced obesity,46 suggesting that muscle microvascular insulin resistance may contribute to the pathogenesis of metabolic insulin resistance and thus the muscle microvasculature could be a therapeutic target for the prevention and management of insulin resistance and T2DM.47

Insulin resistance is also associated with a reduction of muscle capillary density (capillary rarefaction),48–50 which correlates with the severity of insulin resistance.49,51,52 Potential contributors to capillary rarefaction include aberrant expression and action of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family of proteins.53 VEGF recruits and differentiates endothelial progenitor cells and induces endothelial cell proliferation and migration, leading to new vessel formation.53 Muscle-specific VEGF deletion induces muscle capillary rarefaction and insulin resistance54,55 and, in the insulin resistant state, VEGF action on muscle vasculature is impaired, which triggers muscle capillary regression.48,56

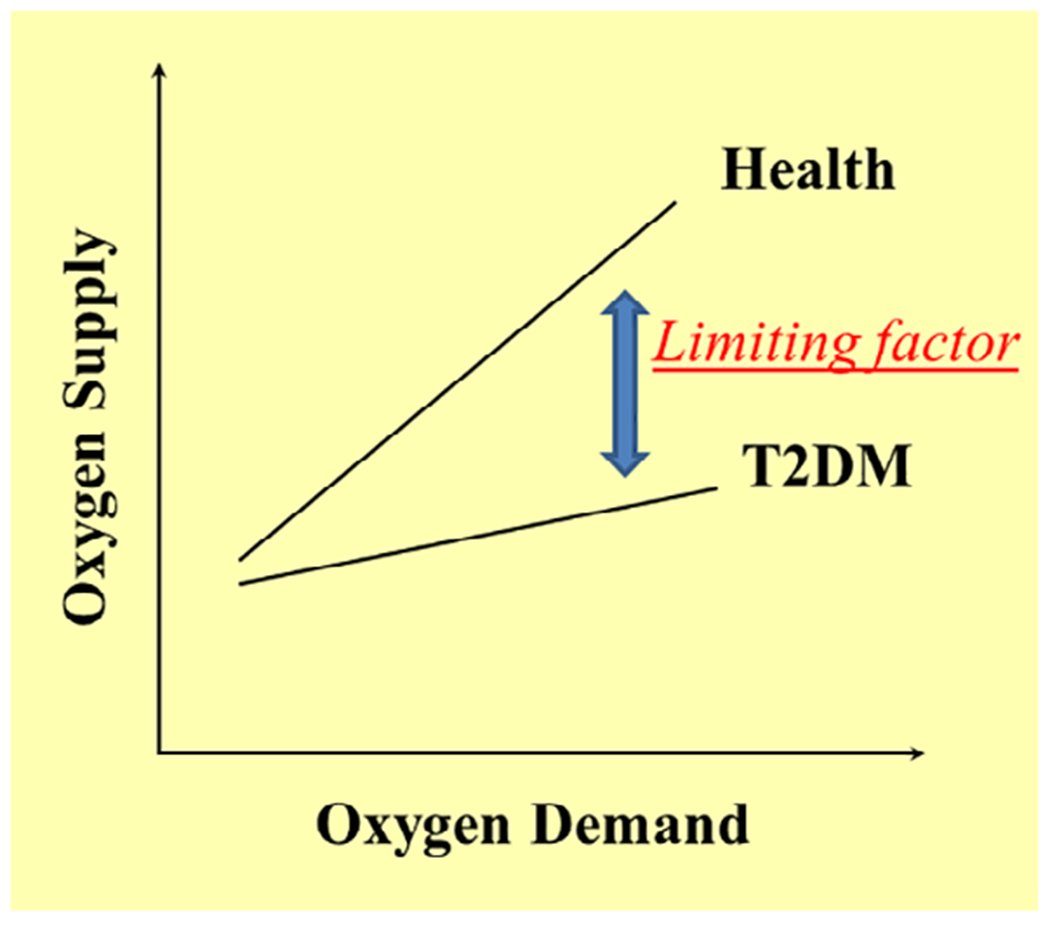

The ominous combination of reduced insulin-mediated microvascular recruitment and capillary rarefaction in T2DM threatens tissue health and function by reducing the microvascular surface area and the delivery and extraction of oxygen, nutrients, and insulin to muscle cells (Figure 2). Although lifestyle modification is very effective in preventing and managing T2DM, many people with T2DM are unwilling or unable to engage in regular exercise. One important contributor to this lifestyle modification “noncompliance or nonadherence” may be a decreased functional exercise capacity in people with T2DM, a well-observed phenomenon.57–60 In a series of reports, we demonstrated a relationship between decreased cardiac and skeletal muscle perfusion and decreased maximal exercise capacity (Figure 3). For example, using near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), we observed slowed skeletal muscle blood flow kinetics at the onset of exercise correlating with slowed oxygen consumption (VO2) kinetics in people with T2DM.61 We further demonstrated that the established positive correlation between muscle deoxyhemoglobin and peak oxygen consumption (VO2peak) in sedentary overweight controls was not present in people with T2DM.62 To confirm that these differences represent an oxygen supply and demand mismatch in people with T2DM, we demonstrated that lower in vivo oxidative flux in T2DM, measured using 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31PMRS), could be corrected with oxygen supplementation (only in people with diabetes).62,63

FIGURE 2.

Muscle microvascular insulin resistance and capillary rarefaction in type 2 diabetes mellitus

FIGURE 3.

Muscle oxygen demand and supply mismatch in type 2 diabetes mellitus

Microvascular insulin resistance and the associated decrease in insulin-mediated muscle perfusion may have also contributed to the development of muscle atrophy/sarcopenia, a well-recognized phenomenon in humans with T2DM.64 In addition to affecting muscle supply of oxygen and nutrients, deliveries of insulin and related growth factors such as IGF-I, both potent activators of muscle protein synthesis and inhibitors of proteolysis,65,66 may also be reduced. Thus, attenuation of microvascular insulin resistance and capillary rarefaction in people with T2DM carries the potential of preventing and reversing muscle atrophy/sarcopenia, leading to further increase in exercise capacity.

4 |. GLP-1 IMPROVES ENDOTHELIAL FUNCTION, INCREASES MUSCLE MICROVASCULAR PERFUSION, AND STIMULATES ANGIOGENESIS

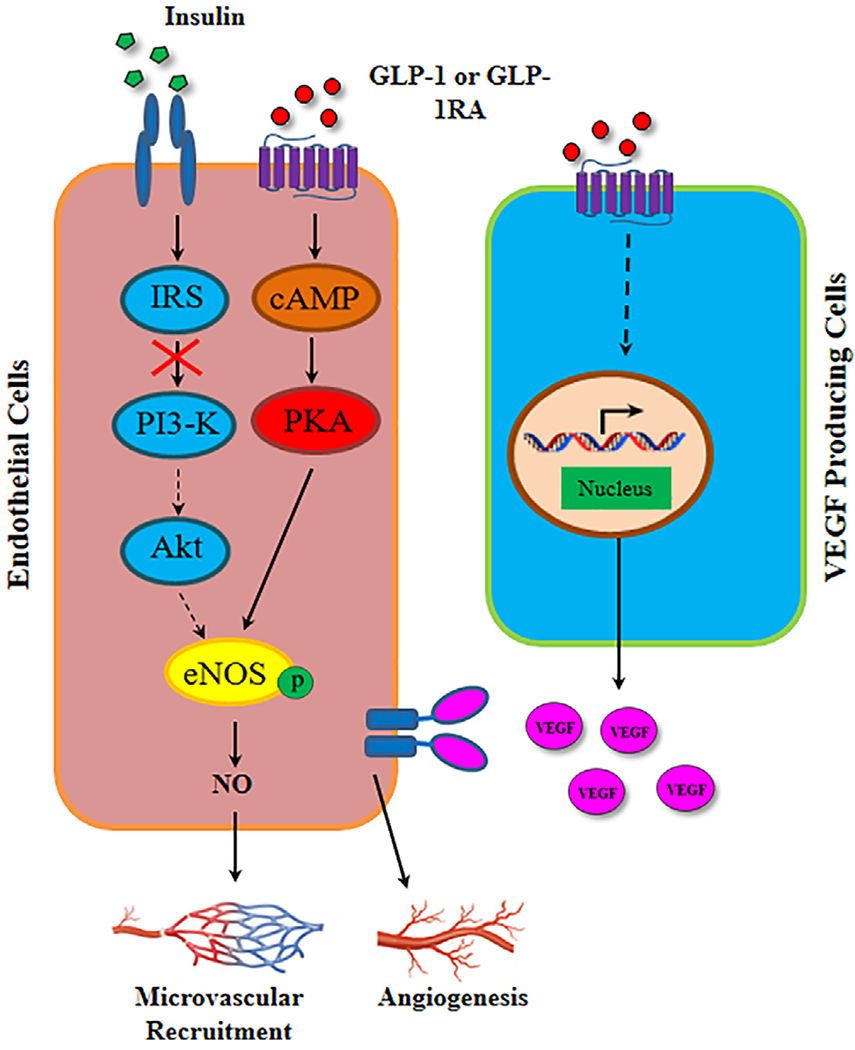

GLP-1R is widely expressed in the cardiovascular system and, in addition to its well-characterized glycemic actions, GLP-1 exerts a variety of cardiovascular actions in both humans and laboratory animals. GLP-1 infusion increases acetylcholine-induced vasodilatation in healthy humans67 and attenuates hypertension and enhances vasodilator response to acetylcholine in Dahl salt-sensitive rats.68 We have recently shown that GLP-1 infusion acutely increases muscle microvascular recruitment independent of insulin secretion in both rats and healthy humans,69,70 likely via a protein kinase A-mediated eNOS activation.69,71 This increase in muscle microvascular perfusion after GLP-1 administration is associated with a robust increase in muscle insulin action and muscle interstitial oxygenation.72 Although we previously observed that systemic GLP-1 infusion at pharmacological concentrations increases both muscle microvascular perfusion and glucose use in rats,69 intra-arterial infusion of GLP-1 at physiological concentrations, in the presence or absence of octreotide infusion to block endogenous insulin infusion, increased muscle microvascular perfusion without increase glucose uptake in humans.73 Whether pharmacological concentrations of GLP-1 increases muscle use of glucose independent of insulin in humans remains to be examined.

Furthermore, GLP-1 and GLP-1R agonists are able to stimulate endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis, which further expand the microvascular blood volume and increase the endothelial exchange surface area. In vitro, incubation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells with GLP-1 dose-dependently promotes angiogenesis.74 Exendin-4, a GLP-1R agonist, induces endothelial cell proliferation75 and increases cell migration in scratch wound assays as well as vessel sprouting in 3D bead assays.76 To date, evidence supporting GLP-1 or GLP-1R agonists’ impact on angiogenesis in vivo is lacking.

GLP-1 also significantly improves cardiac perfusion and function.77 Similar to its effects on the skeletal muscle microvascular bed, infusing GLP-1 to raise the plasma GLP-1 levels to those seen postprandially potently increases cardiac microvascular perfusion in healthy humans.70,78 GLP-1 has been shown to increase myocardial glucose uptake and improve left ventricular performance in dogs,79,80 increase coronary blood flow and myocardial glucose uptake in perfused rat hearts,81 and reduce the infarct size induced by ischemia-reperfusion injury in rodents.82 In patients with acute myocardial infarction, GLP-1 infusion for 72 hours improves the ejection fraction following successful reperfusion.83 Conversely, GLP-1R null mice exhibit an increased left ventricular thickness and end-diastolic pressure and an impaired left ventricular contractility.84 It is important to note that GLP-1-stimulated increases in coronary blood flow and myocardial glucose uptake are independent of insulin.85 In addition, GLP-1 receptors are expressed infrequently in the ventricular myocytes but abundantly in vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, suggesting a vasculature-related cardiac effect.86,87

5 |. GLP-1’S MICROVASCULAR ACTION IS PRESERVED IN THE INSULIN RESISTANT STATES

Importantly, GLP-1’s microvascular action is preserved in the insulin resistant states. We have previously reported in rats that acute infusion of GLP-1 potently increases skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion in both acute (lipid infusion) and chronic (high fat diet feeding) insulin resistant states.72 In humans with class 1 obesity who display microvascular insulin resistance in both skeletal and cardiac muscle microvasculature, GLP-1 at physiological concentrations remains effective in increasing skeletal and cardiac microvascular perfusion.88 In humans with T2DM, GLP-1 infusion improves flow-mediated dilatation.89 The potential clinical relevance is further clarified in rats fed a high-fat diet for 4 weeks that treatment with a GLP-1R agonist liraglutide not only restores insulin-mediated skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion but also prevents high-fat diet-induced reduction in muscle capillary density.90 Taken overall, the data suggest that treatment of insulin resistant humans with GLP-1R agonists may improve muscle microvascular insulin responses and could increase muscle capillarization; both contribute to the expansion of muscle microvascular perfusion. This is of high physiological and clinical importance as it is in the microcirculation where substrate and oxygen delivery and extraction take place and a relatively small increase in the microvascular surface area could markedly increase substrate and oxygen extraction by the tissue (skeletal muscle and myocardium), particularly in the presence of limited total blood flow, as seen in humans with T2DM and atherosclerosis. Given that GLP-1 has been shown to reduce hyperglycemia-induced oxidative species production and apoptotic index in human myocardial endothelial cells91 and increase muscle oxygenation,69,72 and liraglutide treatment restores insulin-mediated increases in muscle oxygenation in insulin resistant rats on a high-fat diet,90 studies on the effects of GLP-1R agonism on functional exercise capacity and cardiac function are warranted. In a more chronic setting involving subjects with recently diagnosed T2DM, 6 months of liraglutide treatment improved arterial stiffness, left ventricular myocardial strain, and endothelial function and reduced oxidative stress.92

6 |. REFLECTIONS ON GLP-1R AGONIST CLINICAL TRIALS

The beneficial metabolic and microvascular actions of GLP-1 and GLP-1R agonist summarized in this article imply that GLP-1 is a physiological regulator of metabolic milieu and microvascular function and thus the use of GLP-1R agonist may confer benefits related to improved metabolism and circulatory function in patients with T2DM. Indeed, out of the six multicentered, randomized placebo-controlled cardiovascular outcome trials (Table 1) evaluating safety of GLP-1R agonist therapies in individuals with T2DM, four demonstrated cardiovascular disease (CVD) benefits. The LEADER trial compared liraglutide (1.8 mg/day, or maximum dose tolerated) with placebo in 9340 participants (81.3% with established CVD) and demonstrated a reduced cardiovascular mortality (4.7% liraglutide vs 6.0% placebo, hazard ratio [HR] 0.78, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.66-0.93; P = 0.007) and all-cause mortality (8.2% vs 9.6% respectively, HR 0.85; 95%CI 0.74-0.97; P = 0.02).93 The SUSTAIN-6 trial randomized 3297 subjects with high CVD risk (83% with established CVD or chronic kidney disease) to semaglutide (0.5 mg or 1.0 mg weekly) or placebo with standard of care.94 The primary composite outcome of major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) defined as first occurrence of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke occurred in 6.6% of semaglutide group and 8.9% of placebo group (HR 0.74%, 95% CI 0.58-0.95, P < 0.001 for noninferiority). Nonfatal stroke was also significantly reduced (1.6% vs 2.7%, HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.38-0.99; P = 0.04).94 Similarly, in the Harmony Outcomes trial, in which 9463 participants with CVD were randomized to albiglutide (30-50 mg weekly) or placebo, combined MACE was reduced in the treatment group (7% vs 9%, HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.68-0.90, P < 0.0001 for noninferiority; P = 0.0006 for superiority), which was predominantly driven by reduced nonfatal myocardial infarction (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.61-0.90).95 Most recently, the REWIND trial comparing dulaglutide (1.5 mg weekly) to placebo demonstrated reduced combined MACE with dulaglutide treatment (12.0% vs 13.4%, HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.79-0.99; P = 0.026) in 9901 participants with a relatively lower rate of preexisting CVD (31.5%) compared with the prior studies.96 Importantly, this trial suggests a role for GLP-1R agonists in primary, in addition to secondary, CVD prevention.

TABLE 1.

Acronyms and abbreviations of glucagon-like peptide 1R agonist cardiovascular outcomes trials

| ELIXA | Evaluation of lixisenatide in acute coronary syndrome |

| EXSCEL | Effect of once weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcome in type 2 diabetes |

| Harmony Outcomes | Trial of the effect of albiglutide on major adverse cardiovascular (CV) events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and established CV disease |

| LEADER | Liraglutide effect and action in diabetes: evaluation of cardiovascular outcome results |

| REWIND | Researching cardiovascular events with a weekly incretin in diabetes |

| SUSTAIN-6 | Trial to evaluate cardiovascular and other long-term outcomes with semaglutide in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus |

Two out of six trials showed no decrease in cardiovascular events. In the ELIXA trial, lixisenatide (20 mcg/day) or placebo use in 6068 participants following an acute coronary syndrome event did not result in significant between group differences in composite MACE including hospitalization for unstable angina (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.89-1.17).97 Similarly, the EXSCEL study, which randomized 10 782 participants (73.1% with preexisting CVD) to extended-release exenatide (2.0 mg weekly) or placebo, showed a nonstatistically significant trend toward improved composite MACE (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.83-1.0, P = 0.06 for superiority, P < 0.001 for noninferiority).98 The reasons behind the discordant results in the cardiovascular outcomes in the use of GLP-1R agonists in humans with T2DM are likely multifactorial, including heterogeneity in disease, patient population and treatment regimens, and a lack of bioequivalence among the agents. For example, exenatide and lixisenatide are least structurally homologous to endogenous GLP-199 and duration of action and structure of these agents may be important predictors of biologic activity. More studies are clearly needed.

These cardiovascular outcomes trials also demonstrated that GLP-1R agonists are beneficial in the prevention and management of the microvascular complications of diabetes. The LEADER, SUSTAIN-6, and REWIND trials showed that the GLP-1R agonists liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide were each associated with a statistically significant reduction in new or progressive nephropathy.93,94,96 A recent meta-analysis (n = 11 399) confirmed a reduced incidence of nephropathy with GLP-1R agonist treatment compared with placebo (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60-0.92, P = 0.005).100 Interestingly in the SUSTAIN-6 trial rates of retinal complications (vitreous hemorrhage, blindness, or conditions requiring intravitreal agent or photocoagulation) were higher (HR 1.76; 95% CI 1.11-2.78, P = 0.02) with semaglutide treatment.94 A possible explanation for the retinopathy progression seen only in the SUSTAIN-6 trial is the substantial improvement in hemoglobin A1c (−1.1% in the 0.5 mg group, −1.4% in the 1.0 mg group) because rapid improvement in glycemic control has been shown to transiently worsen retinopathy, particularly in type 1 diabetes.94,101

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial conducted at 191 clinical sites in 27 countries comparing the effects of liraglutide (3 mg daily) vs placebo in people with prediabetes and obesity, the time to onset of diabetes over 160 weeks among all randomized individuals was 2.7 times longer with liraglutide (n = 1505) than with placebo (n = 749), corresponding with an HR of 2.1.102 This is important as it suggests that GLP-1R agonists can be used to delay new onset of diabetes in humans at risk of developing the disease. Given that insulin’s vascular action contributes to insulin’s metabolic action, microvascular insulin resistance occurs well before the metabolic insulin resistance, and GLP-1’s microvascular actions are preserved in the insulin resistant states, we argue that a GLP-1R agonist should be used early during the disease pathogenesis stage.

7 |. CONCLUSIONS

Insulin and GLP-1 are both vasoactive and able to increase the perfusion of skeletal and cardiac muscle microvasculature, resulting in an expansion of the microvascular exchange surface area and thus the delivery of oxygen, nutrients, and hormones such as insulin to the skeletal and cardiac muscle and thereby promoting skeletal and cardiac muscle health and function. In insulin resistant states such as obesity and T2DM, insulin’s vascular effect is substantially diminished or abolished whereas the physiologic actions of GLP-1 on the microvasculature are preserved. GLP-1R agonists, a mainstay in obesity and T2DM management, are vasoactive and able to stimulate endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis (Figure 4). In large, multicentered clinical trials, four GLP-1RAs have demonstrated improved cardiovascular outcomes in patients with T2DM. GLP-1 agonists also delayed the new onset of T2DM in people at risk, likely related to these salutary properties. Future studies should further examine the different roles of GLP-1 in cardiac as well as skeletal muscle function and the natural history of cardiac and skeletal muscle dysfunction in people with and at risk for T2DM.

FIGURE 4.

Microvascular actions of glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 and GLP-1R agonists in type 2 diabetes mellitus. VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

Highlights.

Skeletal and cardiac muscle microvasculature critically regulates tissue perfusion and the delivery of nutrients, oxygen, and hormones and thus the health and function of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Both insulin and GLP-1 increase skeletal and cardiac muscle microvascular perfusion but insulin’s action is blunted whereas GLP-1’s effect is preserved in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. This may contribute to the salutary cardiovascular protective effects of the GLP-1 receptor agonists seen in multiple clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health Grants (R01HL094722 and R01DK102359 to Z.L., and F32DK121431 to K.L.) and the American Diabetes Association (1-17-ICTS-059) (to Z.L.).

Funding information

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant/Award Number: R01HL094722; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant/Award Numbers: F32DK121431, R01DK102359; American Diabetes Association, Grant/Award Number: 1-17-ICTS-059

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferrannini E, Simonson DC, Katz LD, et al. The disposal of an oral glucose load in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Metabolism. 1988;37:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFronzo RA, Gunnarsson R, Bjorkman O, Olsson M, Wahren J. Effects of insulin on peripheral and splanchnic glucose metabolism in noninsulin-dependent (type II) diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett E, Eggleston E, Inyard A, et al. The vascular actions of insulin control its delivery to muscle and regulate the rate-limiting step in skeletal muscle insulin action. Diabetologia. 2009;52:752–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett EJ, Wang H, Upchurch CT, Liu Z. Insulin regulates its own delivery to skeletal muscle by feed-forward actions on the vasculature. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E252–E263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honig CR, Odoroff CL, Frierson JL. Active and passive capillary control in red muscle at rest and in exercise. Am J Physiol. 1982;243:H196–H206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron AD. Hemodynamic actions of insulin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1994;267:E187–E202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang YJ, Hope ID, Ader M, Bergman RN. Insulin transport across capillaries is rate limiting for insulin action in dogs. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1620–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herkner H, Klein N, Joukhadar C, et al. Transcapillary insulin transfer in human skeletal muscle. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmäng A, Mimura K, Björntorp P, Lsönroth P. Interstitial muscle insulin and glucose levels in normal and insulin-resistant Zucker rats. Diabetes. 1997;46:1799–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castillo C, Bogardus C, Bergman R, Thuillez P, Lillioja S. Interstitial insulin concentrations determine glucose uptake rates but not insulin resistance in lean and obese men. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinberg HO, Brechtel G, Johnson A, Fineberg N, Baron AD. Insulin-mediated skeletal muscle vasodilation is nitric oxide dependent. A novel action of insulin to increase nitric oxide release. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1172–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vincent MA, Clerk LH, Lindner JR, et al. Microvascular recruitment is an early insulin effect that regulates skeletal muscle glucose uptake in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53:1418–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vincent MA, Barrett EJ, Lindner JR, Clark MG, Rattigan S. Inhibiting NOS blocks microvascular recruitment and blunts muscle glucose uptake in response to insulin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E123–E129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jayaweera AR, Wei K, Coggins M, Bin JP, Goodman C, Kaul S. Role of capillaries in determining CBF reserve: new insights using myocardial contrast echocardiography. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;277:H2363–H2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laine H, Nuutila P, Luotolahti M, et al. Insulin-induced increment of coronary flow reserve is not abolished by dexamethasone in healthy young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1868–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laine H, Sundell J, Nuutila P, et al. Insulin induced increase in coronary flow reserve is abolished by dexamethasone in young men with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes. Heart. 2004;90:270–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jagasia D, Whiting JM, Concato J, Pfau S, McNulty PH. Effect of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus on myocardial insulin responsiveness in patients with ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2001;103:1734–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundell J, Laine H, Nuutila P, et al. The effects of insulin and short-term hyperglycaemia on myocardial blood flow in young men with uncomplicated Type I diabetes. Diabetologia. 2002;45:775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sundell J, Nuutila P, Laine H, et al. Dose-dependent vasodilating effects of insulin on adenosine-stimulated myocardial blood flow. Diabetes. 2002;51:1125–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei K, Jayaweera AR, Firoozan S, Linka A, Skyba DM, Kaul S. Quantification of myocardial blood flow with ultrasound-induced destruction of microbubbles administered as a constant venous infusion. Circulation. 1998;97:473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei K, Skyba DM, Firschke C, Jayaweera AR, Lindner JR, Kaul S. Interactions between microbubbles and ultrasound: in vitro and in vivo observations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Z. Insulin at physiological concentrations increases microvascular perfusion in human myocardium. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1250–E1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Jahn LA, Fowler DE, Barrett EJ, Cao W, Liu Z. Free fatty acids induce insulin resistance in both cardiac and skeletal muscle microvasculature in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:438–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chai W, Liu J, Jahn LA, Fowler DE, Barrett EJ, Liu Z. Salsalate attenuates free fatty acid-induced microvascular and metabolic insulin resistance in humans. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1634–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinberg HO, Chaker H, Leaming R, Johnson A, Brechtel G, Baron AD. Obesity/insulin resistance is associated with endothelial dysfunction. Implications for the syndrome of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2601–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinberg HO, Tarshoby M, Monestel R, et al. Elevated circulating free fatty acid levels impair endothelium-dependent vasodilation. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1230–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hogikyan RV, Galecki BP, Halter JB, Greene DA, Supiano MA. Specific impairment of endothelium-dependent vasodilation in subjects with type 2 diabetes independent of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1946–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preik M, Kelm M, Rösen P, Tschöpe D, Strauer BE. Additive effect of coexistent type 2 diabetes and arterial hypertension on endothelial dysfunction in resistance arteries of human forearm vasculature. Angiology. 2000;51:545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clerk LH, Vincent MA, Barrett EJ, Lankford MF, Lindner JR. Skeletal muscle capillary responses to insulin are abnormal in late-stage diabetes and are restored by angiogensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1804–E1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallis MG, Wheatley CM, Rattigan S, Barrett EJ, Clark ADH, Clark MG. Insulin-mediated hemodynamic changes are impaired in muscle of Zucker obese rats. Diabetes. 2002;51:3492–3498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clerk LH, Vincent MA, Jahn LA, Liu Z, Lindner JR, Barrett EJ. Obesity blunts insulin-mediated microvascular recruitment in human forearm muscle. Diabetes. 2006;55:1436–1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundell J, Laine H, Luotolahti M, et al. Obesity affects myocardial vasoreactivity and coronary flow response to insulin. Obes Res. 2002;10:617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Liu Z. Muscle insulin resistance and the inflamed microvasculature: fire from within. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1793–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youd JM, Rattigan S, Clark MG. Acute impairment of insulin-mediated capillary recruitment and glucose uptake in rat skeletal muscle in vivo by TNF-α. Diabetes. 2000;49:1904–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang N, Chai W, Zhao L, Tao L, Cao W, Liu Z. Losartan increases muscle insulin delivery and rescues insulin’s metabolic action during lipid infusion via microvascular recruitment. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E538–E545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Z, Liu J, Jahn LA, Fowler DE, Barrett EJ. Infusing lipid raises plasma free fatty acids and induces insulin resistance in muscle microvasculature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3543–3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scognamiglio R, Negut C, de Kreutzenberg SV, Tiengo A, Avogaro A. Effects of different insulin regimes on postprandial myocardial perfusion defects in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scognamiglio R, Negut C, De Kreutzenberg SV, Tiengo A, Avogaro A. Postprandial myocardial perfusion in healthy subjects and in type 2 diabetic patients. Circulation. 2005;112:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang ZY, Lin Y-W, Clemont A, et al. Characterization of selective resistance to insulin signaling in the vasculature of obese Zucker (fa/fa) rats. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:447–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.J-a K, Koh KK, Quon MJ. The union of vascular and metabolic actions of insulin in sickness and in health. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:889–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.J-a K, Montagnani M, Koh KK, Quon MJ. Reciprocal relationships between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction: molecular and pathophysiological mechanisms. Circulation. 2006;113:1888–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Potenza MA, Marasciulo FL, Chieppa DM, et al. Insulin resistance in spontaneously hypertensive rats is associated with endothelial dysfunction characterized by imbalance between NO and ET-1 production. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H813–H822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eringa EC, Stehouwer CDA, Merlijn T, Westerhof N, Sipkema P. Physiological concentrations of insulin induce endothelin-mediated vasoconstriction during inhibition of NOS or PI3-kinase in skeletal muscle arterioles. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:464–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eringa EC, Stehouwer CDA, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Ouwehand L, Westerhof N, Sipkema P. Vasoconstrictor effects of insulin in skeletal muscle arterioles are mediated by ERK1/2 activation in endothelium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2043–H2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao L, Fu Z, Wu J, et al. Inflammation-induced microvascular insulin resistance is an early event in diet-induced obesity. Clin Sci. 2015;129:1025–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Z The vascular endothelium in diabetes and its potential as a therapeutic target. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2013;14:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gavin TP, Stallings HW, Zwetsloot KA, et al. Lower capillary density but no difference in VEGF expression in obese vs lean young skeletal muscle in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lillioja S, Young AA, Culter CL, et al. Skeletal muscle capillary density and fiber type are possible determinants of in vivo insulin resistance in man. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:415–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chung AWY, Hsiang YN, Matzke LA, McManus BM, van Breemen C, Okon EB. Reduced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor paralleled with the increased angiostatin expression resulting from the upregulated activities of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 in human type 2 diabetic arterial vasculature. Circ Res. 2006;99:140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frisbee JC. Obesity, insulin resistance, and microvessel density. Microcirculation. 2007;14:289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Solomon TPJ, Haus JM, Li Y, Kirwan JP. Progressive hyperglycemia across the glucose tolerance continuum in older obese adults is related to skeletal muscle capillarization and nitric oxide bioavailability. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1377–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olsson A-K, Dimberg A, Kreuger J, Claesson-Welsh L. VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang K, Breen EC, Gerber H-P, Ferrara NMA, Wagner PD. Capillary regression in vascular endothelial growth factor-deficient skeletal muscle. Physiol Genomics. 2004;18:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonner JS, Lantier L, Hasenour CM, James FD, Bracy DP, Wasserman DH. Muscle-specific vascular endothelial growth factor deletion induces muscle capillary rarefaction creating muscle insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2013;62:572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hazarika S, Dokun AO, Li Y, Popel AS, Kontos CD, Annex BH. Impaired angiogenesis after hindlimb ischemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: differential regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1. Circ Res. 2007;101:948–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Regensteiner JG, Bauer TA, Reusch JEB, et al. Abnormal oxygen uptake kinetic responses in women with type II diabetes mellitus. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Regensteiner JG, Sippel J, McFarling ET, Wolfel EE, Hiatt WR. Effects of non-insulin-dependent diabetes on oxygen consumption during treadmill exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:875–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nadeau KJ, Zeitler PS, Bauer TA, et al. Insulin resistance in adolescents with type 2 diabetes is associated with impaired exercise capacity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3687–3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Regensteiner JG, Bauer TA, Huebschmann AG, et al. Sex differences in the effects of type 2 diabetes on exercise performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bauer TA, Reusch JEB, Levi M, Regensteiner JG. Skeletal muscle deoxygenation after the onset of moderate exercise suggests slowed microvascular blood flow kinetics in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2880–2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mason McClatchey P, Bauer TA, Regensteiner JG, Schauer IE, Huebschmann AG, Reusch JEB. Dissociation of local and global skeletal muscle oxygen transport metrics in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2017;31:1311–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cree-Green M, Scalzo RL, Harrall K, et al. Supplemental oxygen improves in vivo mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation flux in sedentary obese adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2018;67:1369–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park SW, Goodpaster BH, Lee JS, et al. Excessive loss of skeletal muscle mass in older adults with type6 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1993–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Z, Barrett EJ. Human protein metabolism: its measurement and regulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E1105–E1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu Z, Long W, Hillier T, Saffer L, Barrett EJ. Insulin regulation of protein metabolism in vivo. Diab Nutr Metab. 1999;12:421–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Basu A, Charkoudian N, Schrage W, Rizza RA, Basu R, Joyner MJ. Beneficial effects of GLP-1 on endothelial function in humans: dampening by glyburide but not by glimepiride. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1289–E1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu M, Moreno C, Hoagland KM, et al. Antihypertensive effect of glucagon-like peptide 1 in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1125–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chai W, Dong Z, Wang N, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 recruits microvasculature and increases glucose use in muscle via a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Diabetes. 2012;61:888–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Subaran SC, Sauder MA, Chai W, et al. GLP-1 at physiological concentrations recruits skeletal and cardiac muscle microvasculature in healthy humans. Clin Sci (Lond). 2014;127:163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dong Z, Chai W, Wang W, et al. Protein kinase A mediates glucagon-like peptide 1-induced nitric oxide production and muscle microvascular recruitment. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E222–E228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chai W, Zhang X, Barrett EJ, Liu Z. Glucagon-like peptide 1 recruits muscle microvasculature and improves insulin’s metabolic action in the presence of insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2014;63:2788–2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sjoberg KA, Holst JJ, Rattigan S, Richter EA, Kiens B. GLP-1 increases microvascular recruitment but not glucose uptake in human and rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306:E355–E362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aronis KN, Chamberland JP, Mantzoros CS. GLP-1 promotes angiogenesis in human endothelial cells in a dose-dependent manner, through the Akt, Src and PKC pathways. Metabolism. 2013;62:1279–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Erdogdu ӧ, Nathanson D, Sjöholm Å, Nyström T, Zhang Q. Exendin-4 stimulates proliferation of human coronary artery endothelial cells through eNOS-, PKA- and PI3K/Akt-dependent pathways and requires GLP-1 receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;325:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kang H-M, Kang Y, Chun HJ, Jeong J-W, Park C. Evaluation of the in vitro and in vivo angiogenic effects of exendin-4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;434:150–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Drucker DJ. The cardiovascular biology of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2016;24:15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tan AWK, Subaran SC, Sauder MA, et al. GLP-1 and insulin recruit muscle microvasculature and dilate conduit artery individually but not additively in healthy humans. J Endocr Soc. 2018;2:190–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nikolaidis LA, Elahi D, Hentosz T, et al. Recombinant glucagon-like peptide-1 increases myocardial glucose uptake and improves left ventricular performance in conscious dogs with pacing-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;110:955–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nikolaidis LA, Elahi D, Shen Y-T, Shannon RP. Active metabolite of GLP-1 mediates myocardial glucose uptake and improves left ventricular performance in conscious dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2401–H2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao T, Parikh P, Bhashyam S, et al. Direct effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on myocardial contractility and glucose uptake in normal and postischemic isolated rat hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1106–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bose AK, Mocanu MM, Carr RD, Brand CL, Yellon DM. Glucagon-like peptide 1 can directly protect the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Diabetes. 2005;54:146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nikolaidis LA, Mankad S, Sokos GG, et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 in patients with acute myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction after successful reperfusion. Circulation. 2004;109:962–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gros R, You X, Baggio LL, et al. Cardiac function in mice lacking the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2242–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nystrom T. The potential beneficial role of glucagon-like peptide-1 in endothelial dysfunction and heart failure associated with insulin resistance. Horm Metab Res. 2008;40:593–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pyke C, Heller RS, Kirk RK, et al. GLP-1 receptor localization in monkey and human tissue: novel distribution revealed with extensively validated monoclonal antibody. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1280–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Richards P, Parker HE, Adriaenssens AE, et al. Identification and characterization of GLP-1 receptor-expressing cells using a new transgenic mouse model. Diabetes. 2014;63:1224–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang N, Tan AWK, Jahn LA, et al. Vasodilatory actions of glucagon-like peptide 1 are preserved in skeletal and cardiac muscle microvasculature but not in conduit artery in obese humans with vascular insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2019;43:634–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nystrom T, Gutniak MK, Zhang Q, et al. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 on endothelial function in type 2 diabetes patients with stable coronary artery disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E1209–E1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chai W, Fu Z, Aylor KW, Barrett EJ, Liu Z. Liraglutide prevents microvascular insulin resistance and preserves muscle capillary density in high-fat diet-fed rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;311:E640–E648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang D, Luo P, Wang Y, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 protects against cardiac microvascular injury in diabetes via a cAMP/PKA/Rho-dependent mechanism. Diabetes. 2013;62:1697–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lambadiari V, Pavlidis G, Kousathana F, et al. Effects of 6-month treatment with the glucagon like peptide-1 analogue liraglutide on arterial stiffness, left ventricular myocardial deformation and oxidative stress in subjects with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hernandez AF, Green JB, Janmohamed S, et al. Albiglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Harmony outcomes): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1519–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2247–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, et al. Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1228–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li Y, Rosenblit PD. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and cardiovascular risk reduction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Is it a class effect? Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20:113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dicembrini I, Nreu B, Scatena A, et al. Microvascular effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Diabetol. 2017;54:933–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Group TDCCTR. Early worsening of diabetic retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:874–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.le Roux CW, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al. 3 years of liraglutide versus placebo for type 2 diabetes risk reduction and weight management in individuals with prediabetes: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1399–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]