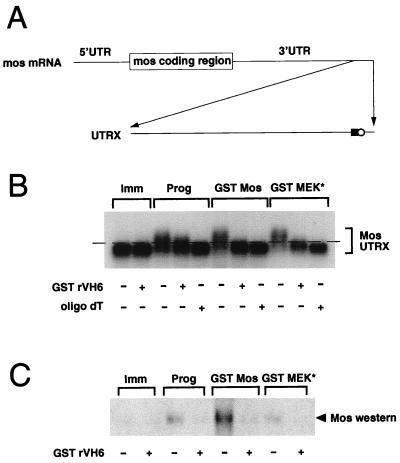

FIG. 2.

MAPK signaling stimulates Mos RNA polyadenylation. (A) Schematic diagram of the synthetic Mos UTRX template. The terminal 321 bp of the Mos 3′ UTR was cloned into pGEM4Z by reverse transcription-PCR, as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of the CPE (solid square) and the nuclear polyadenylation element (AAUAAA) (open circle) are indicated. Prior to in vitro transcription, linearization of the construct with XbaI generated the 321-nucleotide RNA (UTRX), encoding both the CPE and AAUAAA elements. (B and C) Immature oocytes were injected with RNA encoding GST rVH6, as indicated, and left for 14 h to express the protein. The oocytes were then injected with the Mos UTRX and stimulated with progesterone (Prog), coinjected with GST Mos or GST MEK* RNA, or left untreated (Imm). When each separate treatment had reached GVBD70–90 (4 h for progesterone, 9 h for GST Mos, and 23 h for GST MEK*), pools of 10 oocytes were taken for both protein lysates and RNA extraction. (B) A 5-μg portion of total RNA was incubated with RNase H in the presence or absence of oligo(dT) as indicated. RNAs were separated on an agarose gel, and the extent of polyadenylation was analyzed by Northern blotting with a Mos UTR-specific probe as described in Materials and Methods. The dashed line acts as a reference point: RNAs migrating under the line are not polyadenylated, and RNAs migrating above the line are polyadenylated. (C) Endogenous Mos protein accumulation was analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1.