Abstract

Background & Aims

Good outcomes after liver transplantation (LT) have been reported after successfully downstaging to Milan criteria in more advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We aimed to compare post-LT outcomes in patients receiving locoregional therapies (LRT) before LT according to Milan criteria and University of California San Francisco downstaging (UCSF-DS) protocol and ‘all-comers’.

Methods

This multicentre cohort study included patients who received any LRT before LT from Europe and Latin America (2000–2018). We excluded patients with alpha-foetoprotein (AFP) above 1,000 ng/ml. Competing risk regression analysis for HCC recurrence was conducted, estimating subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs) and corresponding 95% CIs.

Results

From 2,441 LT patients, 70.1% received LRT before LT (n = 1,711). Of these, 80.6% were within Milan, 12.0% within UCSF-DS, and 7.4% all-comers. Successful downstaging was achieved in 45.2% (CI 34.8–55.8) and 38.2% (CI 25.4–52.3) of the UCSF-DS group and all-comers, respectively. The risk of recurrence was higher for all-comers (SHR 6.01 [p <0.0001]) and not significantly higher for the UCSF-DS group (SHR 1.60 [p = 0.32]), compared with patients remaining within Milan. The all-comers presented more frequent features of aggressive HCC and higher tumour burden at explant. Among the UCSF-DS group, an AFP value of ≤20 ng/ml at listing was associated with lower recurrence (SHR 2.01 [p = 0.006]) and better survival. However, recurrence was still significantly high irrespective of AFP ≤20 ng/ml in all-comers.

Conclusions

Patients within the UCSF-DS protocol at listing have similar post-transplant outcomes compared with those within Milan when successfully downstaged. Meanwhile, all-comers have a higher recurrence and inferior survival irrespective of response to LRT. Additionally, in the UCSF-DS group, an ALP of ≤20 ng/ml might be a novel tool to optimise selection of candidates for LT.

Clinical trial number

This study was registered as part of an open public registry (NCT03775863).

Lay summary

Patients with more extended HCC (within the UCSF-DS protocol) successfully downstaged to the conventional Milan criteria do not have a higher recurrence rate after LT compared with the group remaining in the Milan criteria from listing to transplantation. Moreover, in the UCSF-DS patient group, an ALP value equal to or below 20 ng/ml at listing might be a novel tool to further optimise selection of candidates for LT.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Downstaging, UCSF downstaging protocol, All-comers, Alpha-foetoprotein

Abbreviations: AC, all-comers; AFP, alpha-foetoprotein; DS, downstaging; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; ITT, intention to treat; LR, liver resection; LRT, locoregional therapies; LT, liver transplantation; MC, Milan criteria; MVI, microvascular invasion; PEI, percutaneous ethanol ablation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; TACE, transarterial chemoembolisation; UCSF-DS, University of California San Francisco downstaging; UNOS, United Network for Organ Sharing; WL, waiting list

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Successful downstaging from UCSF criteria resulted in a similar outcome compared with the group initially within Milan criteria.

-

•

Patients within UCSF-DS criteria and with AFP values below or equal to 20 ng/ml at listing have excellent survival and recurrence rates.

-

•

All-comers have a higher recurrence after downstaging to Milan criteria, with frequent microvascular invasion in the explant.

Introduction

In most countries, the gold standard protocol for liver transplantation (LT) in patients with hepatocellular cancer (HCC) is the Milan criteria (MC).1 However, in recent years, the MC have been challenged for being too strict, unjustifiably excluding specific subgroups with very good outcomes following LT. To broaden the allocation criteria for LT in patients with HCC,2 the expansion of transplant criteria beyond MC has been described based on extended morphometric variables such as the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) criteria3 or by adding markers for biological behaviour such as alpha-foetoprotein (AFP) in the French model4 or the Metro ticket 2.0 model.2,5

In patients exceeding MC, downstaging (DS) with locoregional therapies (LRT) to within conventional transplant criteria has been proposed. In a meta-analysis, the pooled (12 studies) recurrence rate after DS to MC was 0.16 (CI 0.11–0.23). Because of the heterogeneity in data and protocols, the post-LT survival could not be assessed.6 Consequently, as a next step, a priori inclusion criteria were used to maximise the probability of success of DS protocols and reduce the risk of recurrence. Yao et al.7 published the first small prospective study using the University of California San Francisco downstaging (UCSF-DS) protocol as eligibility criteria for enrolment for DS and a minimum of 3 months of observation after the last LRT before LT. The intention-to treat (ITT) outcome of this approach was encouraging, with excellent survival and low recurrence rates following LT.6,7 On the contrary, in patients exceeding the UCSF-DS criteria, defined as ‘all-comers’ (AC), there was a higher waiting list dropout rate, lower DS success, and inferior survival.8 However, from a very recently published retrospective analysis from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), lower 3-year post-LT survival for AC and higher 3-year HCC recurrence rates for both DS groups were observed when compared with MC (6.9% for MC, 12.8% for UNOS-DS, and 16.7% for AC-DS).9 The authors proposed a threshold of AFP values below 100 ng/ml to better select candidates for DS, but even lower values should be addressed. The aim of the present work is therefore to further evaluate the effect of LRT during waiting time on the outcome after LT and for the first time to test the UCSF-DS protocol outside the USA in a large multinational cohort, by comparing the UCSF-DS group with patients within MC. Furthermore, we investigate the group of AC to address the controversy about the existence of an upper limit in tumour burden limiting successful LT after DS. As a third goal, we evaluate variables associated with better post-LT outcomes to define the best subgroup of patients eligible for DS.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective, multicentre, multinational cohort study of patients with HCC who underwent LT in 47 different centres across Europe and Latin America. For that purpose, four databases dealing with patients who underwent transplantation for HCC from different centres in France,4 Italy,10 and Belgium2 between 2000 and 2018 and from Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia, and Mexico11 between 2005 and 2018 were considered. These 4 regional databases were merged, harmonised, quality controlled, and hosted on a central server, after agreement of all participating centres. We grouped patients in different 6-year periods (2000–2005, 2006–2011, and 2012–2018), and we chose a time point of comparison according to the first HCC European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guideline.12 All procedures were followed in accordance with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.13 The ethics committee of each centre approved this study, which complied with ethical standards and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Each investigator was subject to a confidentiality agreement. This study was registered as part of an open public registry (NCT03775863; www.clinicaltrials.gov). We included adult patients (>17 years of age) who underwent a first LT, received any LRT before LT, and were followed up after transplantation. We excluded patients if (1) incidental HCC was found at explant pathology and (2) there were tumours other than HCC found in the explant.

DS groups and common exposure variables

The following variables were collected at each transplant site: recipient characteristics, tumour burden, and AFP serum levels at HCC diagnosis, at listing, and at the last evaluation before LT if available. MC or the AFP score4 were the common standardised patient selection criteria in all centres, but according to local practices and allocation policies, patients exceeding MC or downstaged to MC were also considered and discussed at each transplant centre on a case-by-case basis.

Serum AFP values were categorised as reported by Duvoux et al.4 and further grouped according to lower values including ≤20, 21–100, and 101–1,000 ng/ml (excluding patients with AFP values above 1,000 ng/ml, n = 43).7 Patients were grouped according to tumour burden at listing into 3 groups: (a) meeting MC, (b) exceeding MC but within the UCSF-DS protocol, and (c) AC, exceeding UCSF-DS criteria. The UCSF-DS group was defined according to previously reported criteria, including the following: HCC exceeding MC but with at least 1 of the following tumour size criteria: (a) a single lesion ≤8 cm, (b) 2 or 3 lesions each ≤5 cm and the sum of total tumour diameter ≤8 cm, and (c) 4–5 lesions each ≤3 cm and the sum of total tumour diameter ≤8 cm, as well as in the absence of macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic spread or AFP values above 1,000 ng/ml.7 Patients beyond the UCSF-DS protocol were defined as AC. Of the total study cohort, 1,711 patients received LRT before LT after listing. Tumour treatment and type of LRT were decided at each transplant centre on a case-by-case basis. We focused on patients receiving LRT during the waiting list period with available radiologic tumour reassessment and AFP values before LT (n = 883).14 Successful DS was defined as tumour size and number meeting MC based on imaging measurements of each HCC nodule maximal diameter of viable enhancing lesions and included a decrease in tumour size and number or complete tumour nonenhancement equivalent to complete tumour necrosis. Time on the waiting list after listing and time from LRT to LT were registered.

Pathological tumour features at explant analysis included the presence of microvascular invasion (MVI), tumour differentiation according to Edmondson and Steiner criteria,15 and number and size of each nodule as assessed by experienced pathologists specialised in liver pathology. Necrotic nodules were measured, including necrotic and viable tumour diameter. MC were also assessed at explant pathology.

Main outcomes and statistical analysis

The primary end point analysed was post-LT HCC recurrence. Recurrence was determined based on imaging criteria and serum AFP or by biopsy.16 Secondary end points were successful DS, overall survival, discordance rate between imaging and explant pathology tumour burden, and proportion of MVI and tumour dedifferentiation between patients within MC, patients within UCSF-DS, and AC. Successful DS was defined when a patient exceeding MC at listing was finally within MC at the last tumour reassessment before LT. All patients were followed up until death or the last outpatient visit.

Categorical data were compared using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square (Χ2) test (2-tailed), as appropriate. Continuous variables are shown in mean ± SD or median with IQR and were compared with Student’s t test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test according to their distribution, respectively. Dummies for ordinal or categorical variables were assessed. Multiple comparison for parametric and non-parametric variables were done with ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests, respectively.

For the primary outcome, to avoid selection bias and an overestimation of the risk of recurrence in the presence of competing events, we conducted a multivariable competing risk regression analysis to identify independently associated variables with HCC recurrence, estimating cause-specific hazards (subdistribution hazard ratios [SHRs]) and its corresponding 95% CI using the Fine and Gray method.17 Non-HCC deaths were considered as the competing event for HCC recurrence. To avoid overfitting, for each multivariate model, we followed the rule of 1 independent variable per 10 events included. Variables with a p value of <0.05 in the univariate analysis were included step by step in the multivariate model, evaluating its independent effect on the primary outcome and confounding effect (>20% of change in crude SHR).

For overall survival analysis since transplantation, Kaplan–Meier survival curves were compared using the log-rank test (Mantel–Cox), and Cox proportional regression model with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CI were estimated. Proportional hazard assumption was evaluated through the graphic and Schoenfeld residual test. Collected data were analysed with STATA 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

A total of 2,441 LT patients were included, of which 55.5% were from Europe (n = 1,356) and 44.5% from Latin America (n = 1,085) (Fig. 1.) Participating centres included 20 centres from France (n = 352), 4 from Italy (n = 480), 6 from Belgium (n = 524), 5 from Argentina (n = 325), 3 from Brazil (n = 376), 3 from Chile (n = 90), 2 from Colombia (n = 157), 2 from Mexico (n = 63), and 1 from Ecuador (n = 13), Peru (n = 26), and Uruguay (n = 35). Overall, 70.1% of the patients received at least 1 LRT before LT (n = 1,711). Table S1 describes the main characteristics of patients who received LRT, after excluding 43 patients with AFP values higher than 1,000 ng/ml, according to the definition of the UCSF-DS protocol.7 Overall, 61.6% of the patients (n = 1,027) underwent transplantation before the first HCC EASL guideline was published (2000–2012) and 38.4% after 2012 (n = 641). There was a lower proportion of patients meeting MC at the time of listing when comparing before and after HCC EASL guidelines publication (76.2% vs. 87.5%; p <0.0001). Most patients received transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE; 85.8%) and less frequently radiofrequency ablation (RFA; 20.5%), percutaneous ethanol ablation (PEI; 7.2%), or liver resection (LR; 6.2%). The use of TACE and LR was not significantly different between groups. In the UCSF-DS group, PEI was more frequently performed, and in the AC group, RFA was more frequently performed (Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart study design.

AC, all-comers; AFP, alpha-foetoprotein; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LT, liver transplantation; MC, Milan criteria, UCSF-DS, University of California San Francisco downstaging.

Outcome after LRT in patients achieving effective DS to MC after LRT

Table 1 shows a comparative analysis between longitudinal tumour changes from listing to the last tumour reassessment before LT. In 52.9% of patients receiving LRT, tumour reassessment before LT was available (n = 883). Among these patients, 83.2% (n = 735) were within MC, 10.5% (n = 93) were within UCSF-DS, and 6.2% (n = 55) were AC at the time of listing. The success rate of DS to within the MC at imaging reassessment before LT for the UCSF-DS group was 45.2% (CI 34.8–55.8), whereas for the AC, this was 38.2% (CI 25.4–52.3). In those patients meeting MC at listing, 92.5% (CI 90.4–94.3) remained within MC at the last tumour reassessment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Last imaging reassessment before LT in patients receiving locoregional therapies.

| Variables at last reassessment | Categorisation at listing |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within MC, n = 735 (83.2%) | UCSF-DS, n = 93 (10.5%) | All-comers, n = 55 (6.2%) | p value | |

| Months from reassessment to LT, median (IQR) | 2.2 (1.0–4.3) | 2.3 (0.8–4.2) | 1.9 (0.9–2.9) | 0.48 |

| Within MC, n (%) | 680 (92.5) | 42 (45.2) | 21 (38.2) | <0.0001 |

| Successful DS (95% CI) | 45.2 (34.8–55.8) | 38.2 (25.4–52.3) | ||

Categorical data were compared using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test (2-tailed), as appropriate. Continuous variables are shown in mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) and were compared with Student’s t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test according to their distribution, respectively. DS, downstaging; LT, liver transplantation; MC, Milan criteria; UCSF-DS, University of California San Francisco downstaging.

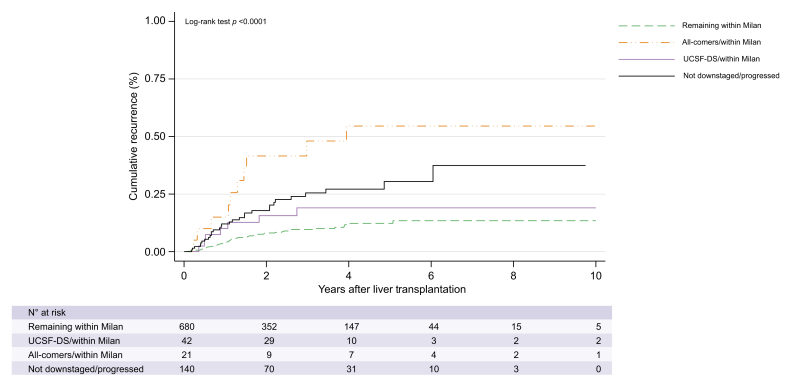

For each group, the outcome after LT was compared according to effective DS to MC. Five-year HCC recurrence rate in patients successfully DS in the UCSF-DS group was 18.2% (CI 9.0–34.7), with a SHR of 1.60 (CI 0.69–4.05, p = 0.32) compared with those patients remaining with MC (13.0% [CI 9.4–17.9]). (Fig. 2). In contrast, the subgroup of AC that could be DS to within the MC had a higher 5-year recurrence rate of 54.7% (CI 33.7–78.2) with a SHR of 6.01 (CI 3.00–12.06; p <0.0001) compared with those remaining within MC. (Fig. 2). The subgroup of patients that progressed to beyond MC or were not DS (n = 140) had a 5-year recurrence rate of 24.3% (CI 11.6–46.8) and a SHR of 2.58 (CI 1.59–4.16, p <0.0001) compared with those remaining within MC (Fig. 2). Patients not DS in the UCSF-DS group presented a significantly higher recurrence rate (24.7% [14.3–40.8]) when compared with those within the UCSF-DS that could be DS with a SHR 3.7 (CI 1.26–11.01; p = 0.017). On the contrary, no significant differences were observed in the AC group either with or without effective DS (SHR 1.86 [CI 0.69–5.63]; p = 0.22) (Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Post-transplant cumulative recurrence among patients receiving locoregional therapies and with tumour reassessment before liver transplantation. unembolden.

Kaplan Meier survival curves were compared using the log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). UCSF-DS, University of California San Francisco downstaging.

Corresponding 4-year survival rates were arithmetically lower in the AC [47.8% (CI 24.5–67.9)] and the group that progressed to beyond MC or were not DS (53.6% [CI 41.7–64.0]) when compared with those patients achieving effective DS in the UCSF-DS group (63.0% [CI 43.9–77.2]) and the MC (64.9% (CI 60.0–69.3)] with no significant difference in survival between groups (p = 0.58) (Fig. S1). Table 2 describes and compares explant pathology findings and tumour burden at the last evaluation in patients receiving LRT and reassessment before LT. In patients achieving MC at the last tumour reassessment, a significant higher discrepancy between radiological tumour burden and pathological tumour burden was observed in the AC group (71.4%) compared with those within the UCSF-DS group (45.2%) and those remaining within MC (27.1%) (Table 2). The proportion of MVI was similar between patients who were successfully DS in the UCSF-DS group (23.8%) and patients remaining within MC. There was a significant higher proportion of MVI observed in the AC group that was not successfully DS (44.1%) and interestingly even after successful DS (52.4%) (Table 2 and Table S2).

Table 2.

Explant pathology findings according to groups at last evaluation in patients receiving locoregional therapies and reassessment before to liver transplantation.

| Variable at explant analysis | Categorisation at last evaluation |

p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within MC, n = 680 (77.0%) | Within UCSF-DS and downstaged to MC, n = 42 (4.8%) | AC and downstaged to MC, n = 21 (2.4%) | Not downstaged or progressed, n = 140 (15.9%) | ||

| Complete necrosis, n (%) | 23 (3.4) | 2 (4.8) | 0 | 5 (3.6) | 0.83 |

| MVI, n (%) | 142 (23.8) | 10 (23.8) | 11 (52.4) | 48 (34.3) | <0.0001 |

| Tumour grade >II, n (%) | 171 (26.4) | 17 (42.5) | 4 (20.0) | 40 (30.5) | 0.12 |

| Within MC, n (%) | 496 (72.9) | 23 (54.8) | 6 (28.6) | 50 (35.7) | <0.0001 |

AC indicates groups initially beyond the UCSF-DS and successfully downstaged to within MC. MC indicates group initially and remaining within MC between listing and last tumour reassessment. UCSF-DS indicates groups initially within the UCSF-DS and successfully downstaged to within MC. Categorical data were compared using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test (2-tailed), as appropriate. AC, all-comers; MC, Milan criteria; MVI, microvascular invasion; UCSF-DS: University of California San Francisco downstaging.

Serum AFP values and cut-off as a useful tool for optimising DS selection criteria

We further evaluated independent prognostic factors at the time of listing associated with HCC recurrence after LT in all patients who received LRT as an ITT analysis for DS (Table 3). AC had a 2-fold increased risk for HCC recurrence, when compared with those meeting the UCSF-DS protocol (SHR 1.9 [CI 1.16–3.07]; p = 0.01). The presence of a major target HCC lesion >6 cm resulted in a 7-fold higher risk of recurrence compared with target lesions ≤3 cm (SHR 6.7 [CI 2.41–18.76]; p <0.0001). Patients presenting AFP values of 21–100 ng/ml (SHR 2.13 [CI 1.25–3.63]) and 101–1,000 ng/ml (SHR 2.59 [CI 1.36–4.94]) presented a higher risk of HCC recurrence independently of tumour burden compared with those patients with AFP values of ≤20 ng/ml. Time on the waiting list, time since the last LRT to transplantation and LT period, and region (Europe vs. Latin America) were not associated with a higher risk of recurrence (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable competing risk regression analysis of independently associated prognostic factors of HCC recurrence in patients receiving LRT attempted to be downstaged (n = 324).

| Unadjusted SHR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted SHR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics at listing | ||||

| Age | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | |||

| Tumour burden | ||||

| UCSF-DS (n = 201) | –- | - | - | - |

| All-comers (n = 123) | 2.18 (1.37-3.45) | <0.0001 | 1.89 (1.16-3.07) | 0.01 |

| Major target lesion | 1.18 (1.07-1.29) | <0.0001 | ||

| ≤3 cm (n = 68) | - | - | - | - |

| 3-6 cm (n = 223) | 3.25 (1.29-8.22) | 0.012 | 3.11 (1.22-7.89) | 0.017 |

| >6 cm (n = 50) | 7.31 (2.70-19.77) | <0.0001 | 6.72 (2.41-18.76) | <0.0001 |

| No. of HCC nodules | 1.03 (0.91-1.16) | 0.60 | ||

| 1-3 nodules (n = 220) | – | - | ||

| ≥4 nodules (n = 121) | 0.86 (0.53-1.42) | 0.56 | ||

| AFP (ng/ml) | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.001 | ||

| ≤20 ng/ml (n = 218) | - | - | - | - |

| 21-100 ng/ml (n = 71) | 1.79 (1.05-3.06) | 0.032 | 2.13 (1.25-3.63) | 0.005 |

| 101–1,000 ng/ml (n = 33) |

2.46 (1.29-4.70) |

<0.0001 |

2.59 (1.36-4.94) |

0.004 |

| WL characteristics | ||||

| WL time | 0.99 (0.97-1.02) | 0.81 | ||

| <3 months (n = 139) | – | - | ||

| 3-6 months (n = 55) | 0.90 (0.48–1.68) | 0.74 | ||

| >6 months (n = 130) | 0.88 (0.53–1.47) | 0.63 | ||

| Time from LRT to LT | ||||

| ≤3 months (n = 59) | 0.99 (0.85–1.15) | 0.91 | ||

| >3 months (n = 27) |

1.04 (0.43–2.52) |

0.92 |

||

| Other confounding factors | ||||

| Region | ||||

| Europe (n = 214) | – | |||

| Latin America (n = 110) | 1.05 (0.64–1.72) | 0.85 | ||

| Period of LT year | ||||

| 2000-2012 (n = 244) | - | – | ||

| 2012-2018 (n = 80) | 1.07 (0.59-1.93) | 0.29 | ||

Fine and Gray method for multivariable competing risk regression analysis to identify independently associated variables with HCC recurrence estimating cause-specific hazards and its corresponding 95% confidence intervals. AFP, alpha-foetoprotein; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; LT, liver transplantation; LRT, locoregional therapies; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio; UCFS-DS, University of California San Francisco downstaging; WL, waiting list.

Consequently, we evaluated if serum AFP values could identify better candidates for DS within the UCSF-DS group at listing. As shown in Fig. 3A, cumulative incidence of HCC recurrence proportionally increased in patients within UCSF-DS with AFP values from ≤20, 21–100, and 101–1,000 ng/ml, with the lowest cumulative incidence observed in those with AFP values below 20 ng/ml (Fig. 3A). From a competing risk regression analysis for HCC cumulative incidence of recurrence, AFP values below 20 ng/ml were associated with lower incidence of HCC recurrence (22.2% [CI 13.5–36.6]) compared with AFP values higher than 20 ng/ml (32.2% [CI 21.1–47.3]) with a SHR of 2.01 (CI 1.02–4.00, p = 0.006). (Fig. 3B). This was also reflected in a higher 5-year survival rate with AFP values of ≤20 ng/ml (70.9% [CI 59.8–79.5]) compared with AFP>20 ng/ml (50.0% [CI 36.1–62.5]; p = 0.001) (Fig. 3C). In the AC group, AFP values below 20 ng/ml were associated with lower risk of recurrence (SHR 2.48 [CI 1.39–4.48]; p = 0.002); however, 5-year recurrence rates were significantly high for both groups of AC presenting AFP ≤20 or >20 ng/ml (32.5% [CI 21.5–47.4] vs. 64.5% [CI 46.1–82.3]). Finally, AFP values below 20 ng/ml at the time of listing and achieving effective DS (n = 63) was associated with a lower risk of recurrence in this subgroup compared with those that were not DS (13.7% [CI 5.3–32.7] vs. 55.0% [CI 31.0–82.1]; SHR 4.43 [CI 1.41–13.92], p = 0.011).

Fig. 3.

Post-LT recurrence (A, B) and survival curves (C) among patients receiving locoregional therapies within UCSF-DS protocol according to AFP values at listing.

(A) Grouped according to AFP values ≤20 ng/ml, 21–100 ng/ml, and 101–1,000 ng/ml. Cumulative incidence curves according to the Fine and Gray method for competing risk regression analysis. (B, C) Grouped according to AFP values ≤20 ng/ml and >20 ng/ml. Kaplan Meier survival curves were compared using the log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). AFP, alpha-foetoprotein; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LT, liver transplantation; UCSF-DS, University of California San Francisco downstaging.

Discussion

The outcome of patients with HCC lesions beyond the conventional MC receiving LT after DS is controversial. The reported higher recurrence rate might be as a result of heterogeneity in data and protocols. In prospective studies, using a stricter inclusion protocol and mandatory waiting period before LT results in similar outcomes compared with MC. This multinational cooperation is the first large, multicentre, cohort study outside the USA to validate the UCSF-DS protocol. We show, for the first time in a non-US cohort, that patients meeting UCSF-DS criteria at listing and successfully downstaged within MC have a similar risk of recurrence when compared with those patients initially and remaining within MC and also have similar 4-year survival rates. A second major finding of this study was that, among the group meeting UCSF-DS, AFP values at listing below or equal to 20 ng/ml identified a subgroup of patients with excellent post-LT survival and lower recurrence rates, thus suggesting that this biomarker should be added as a selection tool in these patients. This trend was even more impressive in patients with AFP <20 ng/ml at listing and achieving effective DS. These two important findings point out the need to maximise DS effort and deliver high consistency in the quality of DS, in particular in patients with favourable tumour biology, to reduce the risk of recurrence in patients with reasonably expanded criteria at listing. Interestingly, although Mehta et al.9 found an AFP value below 100 ng/ml associated with better post-LT outcomes, our results show that a cut-off of 20 ng/ml is even more accurate in selecting the best candidates for DS protocols. This upper limit of AFP was also very recently identified in a study by Lai et al.18 On the contrary, the AC group presented lower survival and higher recurrence rates even when successful DS was achieved. These results confirm that an upper limit in tumour burden exists beyond which successful LT after DS becomes an unrealistic goal.

The lower overall outcome in our cohort compared with that in other studies9,19 can be a result of several factors. All the patients within MC from listing to the last assessment before LT also received LRT to remain within this subgroup. Most cohorts include patients only marginally outside MC before DS. Our study population in the UCSF-DS group was more advanced (22.7% of patients had at least 4 lesions; in 67.8%, the diameter of the largest lesion was 3–6 cm, and in 9.5%, it was more than 6 cm). The success rate of DS in our cohort was also lower than that reported by Yao et al.,19 which was higher than 60%. Two meta-analyses including patients who underwent LT following DS after initial presentation outside the MC showed success rates of DS between 24 and 69%20 or a pooled success rate exceeding 40%.21

We found that only half of the patients who were successfully DS in the UCSF-DS group were finally within MC on explant analysis. When looking further into the results, on explant pathology, 33.3% of the UCSF-DS group had MVI. This indicates that number and size of lesions cannot be the only predictive factor of outcome. Although in the sucessfully UCSF-DS group the rate of MVI was reduced to 23.8%, similarly to the group remaining within MC from listing, the group of AC, although successfully DS, showed a significant higher rate of MVI (52.4%). In other studies, there were no statistically significant differences between the DS and MC groups in all the histologic characteristics,19 or the MVI rate was lower (14.4% of the MC group, 16.9% of UNOS-DS, and 23.7% of AC).9 The importance of MVI as a determinant of tumour behaviour has be extensively studied. The drawback is that this marker can only be assessed on explant, which stresses the need for other surrogates such as AFP values.9,[22], [23], [24], [25] In this regard, we assessed the role of the AFP level in predicting HCC recurrence in the DS group of our cohort and found that the subgroup of patients within the UCSF-DS protocol at listing with an AFP-value of >20 ng/ml had a 2-fold increasing rate of cumulative recurrence compared with the subgroup with an AFP value of ≤20 ng/ml. Consequently, to better select the best candidates for DS within the UCSF-DS protocol, we propose stratification according to AFP values as additional refinements to improve post-LT outcome. The exclusion of patients with an AFP value of >20 ng/ml should be the subject of further research and certainly deserves to be tested in external populations. Future studies should also address if DS to MC is really necessary or if extended criteria taking into account biological factors of tumour behaviour can serve as valuable new targets.[26], [27], [28], [29] Very recently, the first open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial was published including patients with HCC beyond the MC, defining successful DS as partial or complete response to LRT (both surgical and systemic treatments), taking also into account the evolution in AFP and using a 5-year estimated post-LT survival of at least 50% as an inclusion criterion. The study showed that LT improved tumour event-free and overall survival after effective and sustained DS of eligible HCC beyond the MC compared with non-transplant options.30

The limitations of our study include the retrospective acquisition of the data, not taking into account dropouts or ITT outcome given that all included patients underwent transplantation. However, our aim was to evaluate only the post-LT outcomes. Because of the retrospective design of the study, there can be a heterogeneity in LRT regimens and assessment of radiological response between the different centres and within a centre in time. However, to avoid any information bias, data collection and outcome definitions were homogenous across cohorts, and central quality control of all registered data was performed. Furthermore, neither region (Europe vs. Latin America) nor LT period (2001–2011 and 2012–2018) could be withheld as a prognostic factor in multivariable competing risk regression analysis. We also acknowledge that the assessment of DS efficacy was performed on only 50% of the population entering a DS procedure.

In conclusion, a successful DS from UCSF criteria to MC resulted in similar recurrence and survival rates, compared with MC. Moreover, patients within UCSF-DS criteria and with AFP values below or equal to 20 ng/ml at listing have excellent survival and recurrence rates, not only after successful DS, but also when taking into account at the time point of listing. This biomarker might be therefore an additional clinical tool to better select candidates in the UCSF-DS group. On the contrary, AC have a higher recurrence and lower survival rates even after apparently successful DS, with biologically more aggressive tumours observed in the explant pathology analysis, notably frequent MVI. Their exclusion from LT should therefore be considered.

Financial support

There is no financial support to declare.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualisation and methodology: HD, FP, CD. Data collection: FP, HD, CC, AN, IFB, KB, CB, AC, PB, GME, JP, FM, FD, SHD, ES, UC, AG, CV, SF, FR, PB, HVV, DV, MS, CD. Data analysis: FP, FR, HD, CD

Data interpretation: FP, FR, HD, CD. Writing – original draft, review, and editing: HD, FP, CD. Read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript: All authors.

Data availability statement

The dataset during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgements

We thank every co-author who participated in this cohort study.

France: Karim Boudjema, Philippe Bachellier, Filomena Conti, Olivier Scatton, Fabrice Muscari, Ephrem Salame, Pierre Henri Bernard, Claire Francoz, Francois Durand, Sébastien Dharancy, Marie-lorraine Woehl, Claire Vanlemmens, Alexis Laurent, Sylvie Radenne, Jérôme Dumortier, Armand Abergel, Daniel Cherqui, Louise Barbier, Pauline Houssel-Debry, Georges Philippe Pageaux, Laurence Chiche, Victor Deledinghen, Jean Hardwigsen, J. Gugenheim, M. Altieri, Marie Noelle Hilleret, Thomas Decaens, Daniel Cherqui, Christophe Duvoux.

Latin America: Federico Piñero, Aline Lopes Chagas, Paulo Costa, Elaine Cristina de Ataide, Emilio Quiñones, Sergio Hoyos Duque, Sebastián Marciano, Margarita Anders, Adriana Varón, Alina Zerega, Jaime Poniachik, Alejandro Soza, Martín Padilla Machaca, Diego Arufe, Josemaría Menéndez, Rodrigo Zapata, Mario Vilatoba, Linda Muñoz, Ricardo Chong Menéndez, Martín Maraschio, Luis G. Podestá, M. Fauda, A. Gonzalez Campaña, Lucas McCormack, Juan Mattera, Adrian Gadano, Ilka S.F. Fatima Boin, Jose Huygens Parente García, Flair Carrilho, Marcelo Silva.

Italy: Andrea Notarpaolo, Giulia Magini, Lucia Miglioresi, Martina Gambato, Fabrizio Di Benedetto, Cecilia D’Ambrosio, Giuseppe Maria Ettorre, Alessandro Vitale, Patrizia Burra, Stefano Fagiuoli, Umberto Cillo, Michele Colledan, Domenico Pinelli, Paolo Magistri, Giovanni Vennarecci, Marco Colasanti, Valerio Giannelli, Adriano Pellicelli, Cizia Baccaro.

Belgium: Helena Degroote, Hans Van Vlierberghe, Callebout Eduard, Iesari Samuele, Dekervel Jeroen, Schreiber Jonas, Pirenne Jacques, Verslype Chris, Ysebaert Dirk, Michielsen Peter, Lucidi Valerio, Moreno Christophe, Detry Olivier, Delwaide Jean, Troisi Roberto, Lerut Jan Paul.

We appreciate the patients included in this study.

Footnotes

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100331.

Contributor Information

Helena Degroote, Email: Helena.Degroote@Uzgent.be.

French-Italian-Belgium and Latin American collaborative group for HCC and liver transplantation:

Karim Boudjema, Philippe Bachellier, Filomena Conti, Olivier Scatton, Fabrice Muscari, Ephrem Salame, Pierre Henri Bernard, Claire Francoz, Francois Durand, Sébastien Dharancy, Marie-lorraine Woehl, Claire Vanlemmens, Alexis Laurent, Sylvie Radenne, Jérôme Dumortier, Armand Abergel, Daniel Cherqui, Louise Barbier, Pauline Houssel-Debry, Georges Philippe Pageaux, Laurence Chiche, Victor Deledinghen, Jean Hardwigsen, J. Gugenheim, M. Altieri, Marie Noelle Hilleret, Thomas Decaens, Daniel Cherqui, Christophe Duvoux, Federico Piñero, Aline Chagas, Paulo Costa, Elaine Cristina de Ataide, Emilio Quiñones, Sergio Hoyos Duque, Sebastián Marciano, Margarita Anders, Adriana Varón, Alina Zerega, Jaime Poniachik, Alejandro Soza, Martín Padilla Machaca, Diego Arufe, Josemaría Menéndez, Rodrigo Zapata, Mario Vilatoba, Linda Muñoz, Ricardo Chong Menéndez, Martín Maraschio, Luis G. Podestá, M. Fauda, A. Gonzalez Campaña, Lucas McCormack, Juan Mattera, Adrian Gadano, Ilka S.F. Fatima Boin, Jose Huygens Parente García, Flair Carrilho, Marcelo Silva, Andrea Notarpaolo, Giulia Magini, Lucia Miglioresi, Martina Gambato, Fabrizio Di Benedetto, Cecilia D’Ambrosio, Giuseppe Maria Ettorre, Alessandro Vitale, Patrizia Burra, Stefano Fagiuoli, Umberto Cillo, Michele Colledan, Domenico Pinelli, Paolo Magistri, Giovanni Vennarecci, Marco Colasanti, Valerio Giannelli, Adriano Pellicelli, Cizia Baccaro, Helena Degroote, Hans Van Vlierberghe, Callebout Eduard, Iesari Samuele, Dekervel Jeroen, Schreiber Jonas, Pirenne Jacques, Verslype Chris, Ysebaert Dirk, Michielsen Peter, Lucidi Valerio, Moreno Christophe, Detry Olivier, Delwaide Jean, Troisi Roberto, and Lerut Jan Paul

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Mazzaferro V., Regalia E., Doci R., Andreola S., Pulvirenti A., Bozzetti F. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degroote H., Callebout E., Iesari S., Dekervel J., Schreiber J., Pirenne J. Extended criteria for liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma. A retrospective, multicentric validation study in Belgium. Surg Oncol. 2020;33:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao F.Y., Xiao L., Bass N.M., Kerlan R., Ascher N.L., Roberts J.P. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: validation of the UCSF-expanded criteria based on preoperative imaging. Am J Transpl. 2007;7:2587–2596. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duvoux C., Roudot-Thoraval F., Decaens T., Pessione F., Badran H., Piardi T. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a model including alpha-fetoprotein improves the performance of Milan criteria. Gastroenterology. 2012;143 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.052. 986–994 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzaferro V., Sposito C., Zhou J., Pinna A.D., De Carlis L., Fan J. Metroticket 2.0 Model for analysis of competing risks of death after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:128–139. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao F.Y., Hirose R., LaBerge J.M., Davern T.J., 3rd, Bass N.M., Kerlan R.K., Jr. A prospective study on downstaging of hepatocellular carcinoma prior to liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1505–1514. doi: 10.1002/lt.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao F.Y., Kerlan R.K., Jr., Hirose R., Davern T.J., 3rd, Bass N.M., Feng S. Excellent outcome following down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma prior to liver transplantation: an intention-to-treat analysis. Hepatology. 2008;48:819–827. doi: 10.1002/hep.22412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha J., Mehta N., Dodge J.L., Poltavskiy E., Roberts J., Yao F. Are there upper limits in tumor burden for down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma to liver transplant? Analysis of the all-comers protocol. Hepatology. 2019;70:1185–1196. doi: 10.1002/hep.30570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta N., Dodge J.L., Grab J.D., Yao F.Y. National experience on down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma before liver transplant: influence of tumor burden, alpha-fetoprotein, and wait time. Hepatology. 2020;71:943–954. doi: 10.1002/hep.30879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Notarpaolo A., Layese R., Magistri P., Gambato M., Colledan M., Magini G. Validation of the AFP model as a predictor of HCC recurrence in patients with viral hepatitis-related cirrhosis who had received a liver transplant for HCC. J Hepatol. 2017;66:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piñero F., Tisi Baña M., de Ataide E.C., Hoyos Duque S., Marciano S., Varón A. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: evaluation of the alpha-fetoprotein model in a multicenter cohort from Latin America. Liver Int. 2016;36:1657–1667. doi: 10.1111/liv.13159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edmondson H.A., Steiner P.E. Primary carcinoma of the liver: a study of 100 cases among 48,900 necropsies. Cancer. 1954;7:462–503. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195405)7:3<462::aid-cncr2820070308>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kneteman N., Livraghi T., Madoff D., de Santibañez E., Kew M. Tools for monitoring patients with hepatocellular carcinoma on the waiting list and after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17(Suppl. 2):S117–S127. doi: 10.1002/lt.22334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dignam J.J., Zhang Q., Kocherginsky M. The use and interpretation of competing risks regression models. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2301–2308. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai Q., Vitale A., Halazun K., Iesari S., Viveiros A., Bhangui P. Identification of an upper limit of tumor burden for downstaging in candidates with hepatocellular cancer waiting for liver transplantation: a west–east collaborative effort. Cancers. 2020;12:452. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao F.Y., Mehta N., Flemming J., Dodge J., Hameed B., Fix O. Downstaging of hepatocellular cancer before liver transplant: long-term outcome compared to tumors within Milan criteria. Hepatology. 2015;61:1968–1977. doi: 10.1002/hep.27752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon-Weeks A.N., Snaith A., Petrinic T., Friend P.J., Burls A., Silva M.A. Systematic review of outcome of downstaging hepatocellular cancer before liver transplantation in patients outside the Milan criteria. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1201–1208. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parikh N.D., Waljee A.K., Singal A.G. Downstaging hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:1142–1152. doi: 10.1002/lt.24169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bova V., Miraglia R., Maruzzelli L., Vizzini G.B., Luca A. Predictive factors of downstaging of hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria treated with intra-arterial therapies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:433–439. doi: 10.1007/s00270-012-0458-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta N., Guy J., Frenette C.T., Dodge J.L., Osorio R.W., Minteer W.B. Excellent outcomes of liver transplantation following down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma to within Milan criteria: a multicenter study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:955–964. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravaioli M., Grazi G.L., Piscaglia F., Trevisani F., Cescon M., Ercolani G. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: results of down-staging in patients initially outside the Milan selection criteria. Am J Transpl. 2008;8:2547–2557. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piñero F.C.C., Notarpaolo A., Boin I.F., Boudjema K., Baccaro C., Podestá L.G., French Italian Latin American Collaborative Group for HCC and Liver Transplantation Evaluation of the AFP model in patients with low risk recurrence profile: further evidence to support its inclusion for candidate selection. Abstract ILCA. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toso C., Meeberg G., Andres A., Shore C., Saunders C., Bigam D.L. Downstaging prior to liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: advisable but at the price of an increased risk of cancer recurrence – a retrospective study. Transpl Int. 2019;32:163–172. doi: 10.1111/tri.13337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cascales-Campos P., Martinez-Insfran L.A., Ramirez P., Ferreras D., Gonzalez-Sanchez M.R., Sanchez-Bueno F. Liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma outside the Milan criteria after downstaging: is it worth it? Transpl Proc. 2018;50:591–594. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei J., Yan L. Outcome comparisons among the Hangzhou, Chengdu, and UCSF criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma liver transplantation after successful downstaging therapies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1116–1122. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lei J., Yan L. Comparison between living donor liver transplantation recipients who met the Milan and UCSF criteria after successful downstaging therapies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:2120–2125. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-2019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazzaferro V., Citterio D., Bhoori S., Bongini M., Miceli R., De Carlis L. Liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma after tumour downstaging (XXL): a randomised, controlled, phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:947–956. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.