Abstract

Background:

Indications for partial nephrectomy (PN) have expanded to include larger tumors. Compared with radical nephrectomy (RN), PN reduces the risk of chronic kidney disease but is associated with higher morbidity.

Objective:

To explore whether the benefit of PN (preservation of estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2 1 yr postoperatively) over RN is offset by higher morbidity for cT2-cT3a tumors.

Design, setting, and participants:

A total of 1921 patients with renal cortical tumors who underwent nephrectomy between 2000 and 2012 were analyzed, with 297 having clinical stage T2 or higher disease.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis:

Multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for age, tumor size, and comorbidities were used to calculate the risk of complications within 90 d and the risk of low eGFR across a range of tumor sizes. Models were created separately for RN and PN, and the difference between risk estimates was calculated.

Results and limitations:

For tumors with diameters between 7 and 12 cm, the risk of eGFR downgrade associated with RN was higher than the risk of complications associated with PN. The magnitude of the risk of eGFR downgrade was similar to the magnitude of complications risk across all tumor sizes. Our analysis was performed at a single institution, and used only tumor size to compare the risk and benefits of surgery.

Conclusions:

Our study suggests that PN is associated with higher eGFR preservation than RN for cT2 or greater renal tumors. The magnitude of this advantage offsets the higher morbidity observed with PN.

Keywords: Complications, Chronic kidney disease, Nephrectomy, Nephron-sparing surgery, Renal cell carcinoma

Patient summary:

When treating a large kidney tumor, it is difficult to decide whether it is better to remove the whole kidney or remove just the tumor. The second option improves postoperative renal function but is more complex. We tried to find whether there is a tumor size at which one technique should be used over the other.

1. Introduction

Compared with radical nephrectomy (RN), partial nephrectomy (PN) is associated with a decreased risk of postoperative chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1] and potentially lower rates of CKD-related cardiac events and death, constituting a strong argument for wider utilization of PN and expansion of its indications to larger tumors and those in more complex anatomic locations [2,3].

Currently, the upper limit of PN indications remains undefined, and is determined by an individual surgeon’s expertise and preference. The degree of variability in the choice between PN and RN for a given tumor increases with tumor size. Surgeons committed to nephron sparing are likely to expand the indications of PN, while those concerned with increased morbidity and doubtful of the clinical relevance of a moderate decrease in renal function are likely to perform RN, regardless of tumor size.

We hypothesized that the benefit of retained renal function outweighs the risk of complication in patients with tumors of cT2 or greater stage. This work has the potential to increase the likelihood that PN is performed in patients with larger tumors, therefore improving postoperative renal function in those patients.

2. Patients and methods

After institutional review board approval, patients who underwent nephrectomy for renal cortical tumors at our institution between January 2000 and October 2012 were identified. Of 3212 patients, 1921 were eligible for inclusion in this analysis. Patients were excluded if they had other tumors (n = 23), had a benign tumor (n = 84), were missing information on postoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 1 yr (n = 826) or tumor size (n = 19), underwent cytoreductive nephrectomy (n = 207), or had cT3b or higher tumors (n = 70) or tumors with a maximum diameter of >12 cm (n = 62). Patients with a solitary kidney were not included in the query. Patients who had evidence of lymph node involvement before surgery were not included. Of the 1921 eligible patients, 1413 (74%) had a PN and 508 (26%) had an RN. Of the patients with tumors 7 cm or larger (n = 297), 66 (22%) underwent PN and 231 (78%) RN.

Operations were performed by 10 different surgeons, through an open, laparoscopic, or robotic approach. The decision to perform PN or RN was at the surgeon’s discretion. Rates of PN steadily increased over the study period for all surgeons involved, as we have reported previously [4].

Complications within 90 d of surgery were prospectively collected and classified using the Clavien-Dindo grading system [5]. Patients’ pre- and postoperative eGFR values were calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation, with the postoperative eGFR based on the creatinine measurement taken closest to 1 yr after surgery (between 9 and 15 mo postoperatively). The eGFR downgrade was defined as preoperative eGFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and postoperative eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 at 1 yr after surgery.

2.1. Statistical analysis

The main analysis included patients with tumors with maximum diameters between 7 and 12 cm, corresponding to clinical stage T2 and higher. As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the analyses using all patients. Separate logistic regression models were fit for PN and RN to assess the risk of eGFR downgrade by tumor size. The risk of eGFR downgrade in each model was adjusted for age and comorbidities (coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, hypercholesterolemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension). We calculated the risk of eGFR downgrade for patients who underwent RN compared with that for patients who underwent PN at each tumor size. To assess whether their tumor size was associated with outcome after controlling for surgical approach, logistic regression models were created for the outcomes of eGFR downgrade and included tumor size and type of surgery (PN or RN) as covariates.

The risk differences for grade II+ complications between PN and RN were assessed in a similar manner, using logistic regression with risk predictions by tumor size adjusted for age and comorbidities. The risk of complications associated with PN compared with RN was calculated for each tumor size. A separate analysis of grade III+ complications and eGFR downgrade was precluded by the limited number of these events.

The difference in risk differences was calculated as the difference in the risk of complications between PN and RN groups subtracted from the difference in the risk of eGFR downgrade between PN and RN groups. Bootstrap resampling was used to calculate the confidence intervals around the difference in risk differences. A sensitivity analysis was performed using downstage in the CKD classification (stage I [eGFR >90], stage II [eGFR 60–89], stage III [eGFR 30–59], stage IV [eGFR 15–29], and stage V [eGFR <15]) for eGFR downgrade.

All analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

Baseline patient and tumor characteristics are listed for patients with clinical stage T2 or higher disease in Table 1 and for all patients in Table 2. In Supplementary Figure 1, we show the percentage of PN across the timespan of our study. Among patients with clinical stage T2 or higher tumors, median tumor size was 7.8 cm (quartiles 7.3, 8.4) for PN and 9.0 cm (quartiles 8.0, 10.0) for RN. Rates of grade II or higher complications within 90 d were 7.6% (PN) and 6.1% (RN). Among patients with a preoperative eGFR of >60, eGFR downgrade rates were 22% (PN) and 68% (RN). Supplementary Table 1 depicts Clavien 2+ complications.

Table 1 –

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 297 patients with clinical stage T2 or higher treated with nephrectomy

| All patients (n = 297) | Partial nephrectomy (n = 66) | Radical nephrectomy (n = 231) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 202 (68) | 49 (74) | 153 (66) |

| Age (yr) at surgery, median (quartiles) | 59 (51, 67) | 60 (52, 68) | 59 (51, 67) |

| ASA score, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 7 (2.4) | 2 (3.0) | 5 (2.2) |

| 2 | 148 (50) | 32 (48) | 116 (50) |

| 3 | 140 (47) | 32 (48) | 108 (47) |

| 4 | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.9) |

| BMI, median (quartiles) | (n = 296) | (n = 66) | (n = 230) |

| 29 (25, 33) | 29 (26, 33) | 29 (25, 33) | |

| Tumor size (cm), median (quartiles) | 8.5 (7.7, 10.0) | 7.8 (7.3, 8.4) | 9.0 (8.0, 10.0) |

| Side, n (%) | |||

| Left | 141 (47) | 37 (56) | 104 (45) |

| Right | 156 (53) | 29 (44) | 127 (55) |

| Type of nephrectomy, n (%) | |||

| Open | 247 (83) | 48 (73) | 199 (86) |

| Laparoscopic | 38 (13) | 10 (15) | 28 (12) |

| Robot-assisted | 12 (4.0) | 8 (12) | 4 (1.7) |

| Pathologic node-positive disease | 9 (3.0) | 1 (1.5) | 8 (3.5) |

| Preoperative eGFR, median (quartiles) | 66 (57, 78) | 66 (57, 81) | 66 (57, 78) |

| Postoperative eGFR at 1 yr, median (quartiles) | 52 (44, 62) | 62 (51, 75) | 50 (42, 59) |

| Grade II+ complication within 90 d, n (%) | 20 (6.7) | 5 (7.6) | 15 (6.5) |

| eGFR downgrade, among patients with preoperative eGFR >60, n (%) | (n = 205) | (n = 45) | (n = 160) |

| 118 (58) | 10 (22) | 108 (68) | |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI = body mass index; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Table 2 –

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 1921 patients treated with nephrectomy

| All patients (n = 1921) | Partial nephrectomy (n = 1413) | Radical nephrectomy (n = 508) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 1232 (64) | 923 (65) | 309 (61) |

| Age (yr) at surgery, median (quartiles) | 61 (52, 69) | 60 (52, 68) | 61 (52, 70) |

| ASA score, n (%) | (n=1,920) | (n=1,412) | (n=508) |

| 1 | 81 (4.2) | 64 (4.5) | 17 (3.3) |

| 2 | 998 (52) | 723 (51) | 275 (54) |

| 3 | 823 (43) | 613 (43) | 210 (41) |

| 4 | 18 (0.9) | 12 (0.8) | 6 (1.2) |

| BMI, median (quartiles) | (n = 1901) | (n = 1395) | (n = 506) |

| 29 (26, 32) | 29 (26, 32) | 29 (25, 33) | |

| Tumor size (cm), median (quartiles) | 3.9 (2.7, 5.6) | 3.3 (2.5, 4.4) | 6.5 (4.9, 8.6) |

| Side, n (%) | |||

| Left | 947 (49) | 709 (50) | 238 (47) |

| Right | 974 (51) | 704 (50) | 270 (53) |

| Type of nephrectomy, n (%) | |||

| Open | 1581 (82) | 1148 (81) | 433 (85) |

| Laparoscopic | 214 (11) | 145 (10) | 69 (14) |

| Robot-assisted | 126 (6.5) | 120 (8.5) | 6 (1.2) |

| Pathologic node-positive disease | 22 (1.1) | 4 (0.3) | 18 (3.5) |

| Preoperative eGFR, median (quartiles) | 68 (57, 81) | 69 (58, 82) | 67 (56, 78) |

| Postoperative eGFR at 1 yr, median (quartiles) | 61 (49, 75) | 67 (54, 80) | 48 (40, 56) |

| Grade II+ complication within 90 d, n (%) | 150 (7.8) | 115 (8.1) | 35 (6.9) |

| eGFR downgrade, among patients with preoperative eGFR >60, n (%) | (n = 1327) | (n = 982) | (n = 345) |

| 422 (32) | 168 (17) | 254 (74) | |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI = body mass index; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Figure 1 shows the risk of complications by tumor size for patients receiving PN and RN. While there was a significant association between tumor size and complications after adjusting for surgery type, complication rates were low for both PN and RN over all tumor sizes, and wide confidence intervals suggest no clinically important difference in complication rates (p = 0.010). We compared the risk of eGFR downgrade by tumor size between patients who underwent PN and those who underwent RN (Fig. 2). The risk of eGFR downgrade is lower in PN patients across all tumor sizes, but the difference in the risk of eGFR downgrade between PN and RN patients does not appear to be associated with tumor size (p = 0.7).

Fig. 1 –

Risk of complications by tumor size in patients with clinical stage T2 or higher disease treated with radical nephrectomy (black line) and partial nephrectomy (gray line), with 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines).

Fig. 2 –

Risk of eGFR downgrade by tumor size in patients with clinical stage T2 or higher disease treated with radical nephrectomy (black line) and partial nephrectomy (gray line), with 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines). The eGFR downgrade was defined as preoperative eGFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and postoperative eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 at 1 yr after operation. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate.

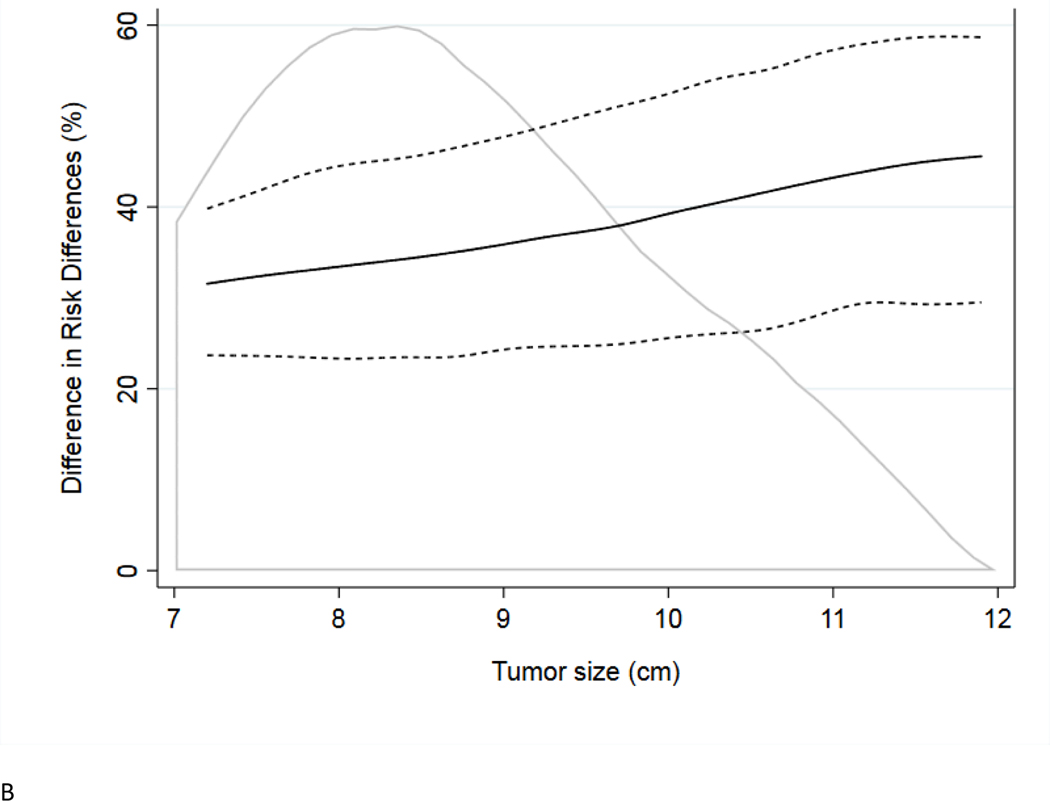

We sought to compare the risk of eGFR downgrade from RN with the risk of complications from PN across a range of tumor sizes. Toward this end, we calculated the difference in risk differences, which is the difference in the risk of complications between PN and RN groups subtracted from the difference in the risk of eGFR downgrade between PN and RN groups. We compared the difference in risk differences using two definitions of eGFR downgrade (Fig. 3). We confirmed the sensitivity of our analysis in which eGFR downgrade was defined as preoperative eGFR >60 to postoperative eGFR <60 (Fig. 3A) by using CKD classification downstage to calculate the difference in risk differences (Fig. 3B). In both analyses, the regression line is relatively flat and close to 40%, indicating that the risk of eGFR downgrade associated with RN is about 40% higher than the risk of complications associated with PN. Importantly, this does not vary greatly for tumors between 7 and 12 cm in diameter. As a sensitivity analysis, we also repeated these analyses including patients with tumors between 1 and 12 cm, with similar results (Supplementary Fig. 2). The risk of eGFR downgrade associated with RN was 40–50% higher than the risk of complications associated with PN, with little difference across tumor sizes.

Fig. 3 –

Difference in risk differences by tumor size, with 95% confidence interval, for tumors the maximum diameter between 7 and 12 cm. Area graph (light gray) represents distribution of tumor sizes. The solid black line represents the difference between the risk difference for eGFR downgrade and the risk difference for complications, and the black dashed line represents the 95% confidence interval. The eGFR downgrade defined as (A) preoperative eGFR >60 and postoperative eGFR <60 and (B) chronic kidney disease classification downstage. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate.

4. Discussion

Our study aimed to determine whether the benefits associated with PN for the treatment of small renal masses may be applied to larger masses as well, and whether there is a point, based on tumor size, at which the quest to maximize renal function preservation through PN becomes futile and perhaps even detrimental to the patient. Our work indicates that PN confers the benefit of higher renal function preservation with little increase in morbidity risk in patients with cT2b or greater renal cortical tumors.

Refinements in surgical technique in recent years have allowed the expansion of PN indications to include larger tumors, and the desire to maximize renal function preservation has motivated some surgeons to perform PNs to the greatest extent possible [3,6]. A large multi-institutional study demonstrated no significant difference in the rates of local recurrence, metastasis, and cancer-specific mortality between patients treated by PN and those treated by RN for cT1b tumors [7]. Several other reports have established the oncologic validity of PN in carefully selected patients with cT1b or greater tumors [8–10]. However, some reports indicate that PN is associated with slightly higher complication rates than RN [11,12], particularly surgery-related complications such as postoperative bleeding and urinary fistula [13]. Our analysis finds that, for patients who undergo PN, the risk of complications is low and is offset by the magnitude of the benefit of renal function preservation.

The decision to perform PN rather than RN is dependent on several factors besides tumor size, including tumor location, depth, and proximity to large vessels within the kidney, and the functional parenchymal volume to be preserved. A limitation of the present study is that our analysis accounted for tumor size only. We recognize that tools such as nephrometry scores are much more comprehensive than tumor size alone and thus more accurately reflect the complexity of the decision to perform PN or RN [14–16]. Unfortunately, the majority of patients treated in our study were diagnosed elsewhere and, given the timespan of the study, good-quality preoperative imaging was not available to accurately determine their nephrometry scores. However, we believe that tumor size is a valid surrogate for nephrometry score and correlates well with PN outcomes such as long-term renal function preservation and morbidity. This notion has been corroborated by analyses performed by other groups. Mehrazin and colleagues [17] used a dataset of 322 patients who underwent PN at multiple institutions to compare the ability of RENAL nephrometry score and tumor size to predict long-term renal decline after PN, and found no significant difference between them in predicting de novo eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 or decrease of eGFR ≥50% from baseline. Simmons et al [18] studied the association of nephrometry scoring systems with volume loss and renal function recovery using a single-institution dataset of 237 patients who underwent PN. Tumor size and nephrometry scores (RENAL and centrality index) were independent predictors of nadir and late percent GFR preservation. Of the different anatomical parameters, only tumor diameter and distance from the kidney center were associated with functional volume preservation. Larger studies with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm that nephrometry scores correlate with PN-related morbidity and long-term functional and oncologic outcomes.

While our risk-benefit analysis can help surgeons in the decision-making process and in counseling patients about surgical approaches and outcomes, we recognize that our findings solely reflect the practice pattern at our institution and need external validation prior to generalizability. Owing to the retrospective nature of our study, we could not assess other CKD-related factors such as proteinuria and antihypertensive drugs. We also recognize that hospitalization due to surgical complications may not carry the same severity as hospitalization due to CKD. In addition, surgically induced CKD seems to have different clinical implications than pre-existing CKD due to medical causes [19]. In an analysis of the data from the EORTC-30904, Scosyrev and colleagues [20] found that PN did not reduce the incidence of advanced kidney disease (eGFR <30) and kidney failure (eGFR <15) when compared with RN, but it conferred a protective effect that was limited to moderate renal kidney disease (eGFR <60). Although long-term clinical implications of surgically induced moderate kidney disease remain undetermined, a recent retrospective analysis of >3400 patients who underwent kidney surgery for renal cell carcinoma (either RN or PN) found an independent correlation between eGFR and cancer-specific mortality, with a lower eGFR leading to increased cancer-specific mortality [21]. These results support our conclusion that the preservation of renal function through PN, when feasible, outweighs the risk of complications.

5. Conclusions

We aimed to determine whether in cT2 or greater tumors, the benefit of PN in terms of preservation of kidney function is offset by higher surgical morbidity. In cT2 or greater renal tumors, PN offers better renal function preservation than RN with minimal increase in the risk of complications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: This work was supported by the Sidney Kimmel Center for Prostate and Urological Cancers and the Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 to Craig B. Thompson, MD (PI), at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Financial disclosures: Antoni Vilaseca certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Footnotes

We compared the risks and benefits of radical and partial nephrectomy in patients with renal cell carcinoma. We found that the preservation of renal function outweighs the risk of complications for patients who undergo partial nephrectomy.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Huang WC, Levey AS, Serio AM, et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephrectomy in patients with renal cortical tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2006;7:735–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Huang WC, Elkin EB, Levey AS, Jang TL, Russo P. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy in patients with small renal tumors--is there a difference in mortality and cardiovascular outcomes? J Urol 2009;181:55–61; discussion 61–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Touijer K, Jacqmin D, Kavoussi LR, et al. The expanding role of partial nephrectomy: a critical analysis of indications, results, and complications. Eur Urol 2010;57:214–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thompson RH, Kaag M, Vickers A, et al. Contemporary use of partial nephrectomy at a tertiary care center in the United States. J Urol 2009;181:993–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Patard JJ, Pantuck AJ, Crepel M, et al. Morbidity and clinical outcome of nephron-sparing surgery in relation to tumour size and indication. Eur Urol 2007;52:148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Patard JJ, Shvarts O, Lam JS, et al. Safety and efficacy of partial nephrectomy for all T1 tumors based on an international multicenter experience. J Urol 2004;171:2181–5, quiz 2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dash A, Vickers AJ, Schachter LR, Bach AM, Snyder ME, Russo P. Comparison of outcomes in elective partial vs radical nephrectomy for clear cell renal cell carcinoma of 4–7 cm. BJU Int 2006;97:939–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Breau RH, Crispen PL, Jimenez RE, Lohse CM, Blute ML, Leibovich BC. Outcome of stage T2 or greater renal cell cancer treated with partial nephrectomy. J Urol 2010;183:903–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Leibovich BC, Blute M, Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Weaver AL, Zincke H. Nephron sparing surgery for appropriately selected renal cell carcinoma between 4 and 7 cm results in outcome similar to radical nephrectomy. J Urol 2004;171:1066–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lesage K, Joniau S, Fransis K, Van Poppel H. Comparison between open partial and radical nephrectomy for renal tumours: perioperative outcome and health-related quality of life. Eur Urol 2007;51:614–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Van Poppel H, Da Pozzo L, Albrecht W, et al. A prospective randomized EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the complications of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2007;51:1606–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Stephenson AJ, Hakimi AA, Snyder ME, Russo P. Complications of radical and partial nephrectomy in a large contemporary cohort. J Urol 2004;171:130–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kutikov A, Uzzo RG. The R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score: a comprehensive standardized system for quantitating renal tumor size, location and depth. J Urol 2009;182:844–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Simmons MN, Ching CB, Samplaski MK, Park CH, Gill IS. Kidney tumor location measurement using the C index method. J Urol 2010;183:1708–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ficarra V, Novara G, Secco S, et al. Preoperative aspects and dimensions used for an anatomical (PADUA) classification of renal tumours in patients who are candidates for nephron-sparing surgery. Eur Urol 2009;56:786–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mehrazin R, Palazzi KL, Kopp RP, et al. Impact of tumour morphology on renal function decline after partial nephrectomy. BJU Int 2013;111:e374–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Simmons MN, Hillyer SP, Lee BH, Fergany AF, Kaouk J, Campbell SC. Nephrometry score is associated with volume loss and functional recovery after partial nephrectomy. J Urol 2012;188:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Demirjian S, Lane BR, Derweesh IH, Takagi T, Fergany A, Campbell SC. Chronic kidney disease due to surgical removal of nephrons: relative rates of progression and survival. J Urol 2014;192:1057–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Sylvester R, Campbell SC, Van Poppel H. Renal function after nephron-sparing surgery versus radical nephrectomy: results from EORTC randomized trial 30904. Eur Urol 2014;65:372–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Antonelli A, Minervini A, Sandri M, et al. Below safety limits, every unit of glomerular filtration rate counts: assessing the relationship between renal function and cancer-specific mortality in renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2018;74:661–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.