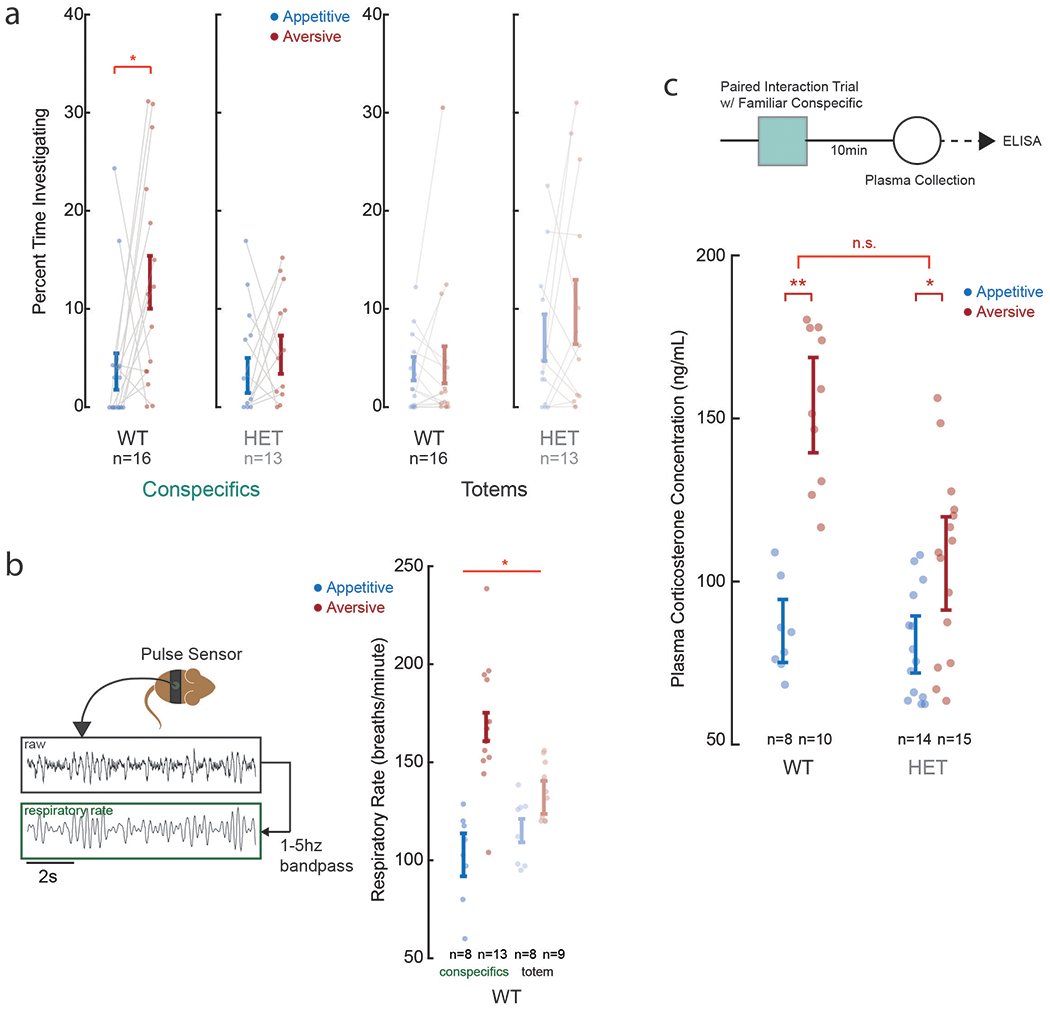

Extended Data Fig. 6. WT animals differentiate between others’ aversive and appetitive experiences.

a. To understand whether animals recognized another animal’s experience and to allow for comparison with our main results, the animals performed a place preference/avoidance task where subjects were presented with two age and sex-matched familiar conspecific partners undergoing either an appetitive (food-baited enclosure) or aversive (confined tube enclosure) experience. The percent time spent by the animals investigating the aversive and appetitive enclosures when in the presence of another animal is shown here. While the WT displayed a significant difference the time spent investigating the specific enclosures when compared to HET animals (*two-tailed unpaired test; ts(15) = −2.79; p = 0.014), there was no difference in approach behavior when familiar conspecifics were replaced with inanimate totems in the enclosures (ANOVA, p > 0.5 post-hoc comparison). b. We confirmed that the WT animals differentiated the other’s experiences based on respiratory rate. Using a mouse jacket (Lomir Biomedical) and pulse sensor (World Famous Electronics; digitized at 500 Hz then band-passed at 1-5 Hz), we find a significant difference in the animal’ respiratory rate when the other animal was having an aversive vs. appetitive experience (*ANOVA, p = 0.0031). c. The panel above displays the sequence of behavioral testing, plasma collection and corticosterone analysis/quantification by ELISA. The panel below displays the plasma levels collected across all WT and HET animals. Here, the levels are given based on whether the animals observed the other having an appetitive vs. aversive experience (two-tailed unpaired t-tests; * p = 0.021, ** p < 0.01, n.s. p = 0.23).