Abstract

Purpose.

Sexual minority women (SMW; e.g., lesbian, bisexual) are more likely than heterosexual women to be heavy drinkers, with bisexual women showing the highest risk. There is ample literature demonstrating that intimate relationships protect against stress-related health risk behaviors in the general population. However, very little research has focused on SMW’s relationships and far less is known about the relationships of SMW of color. Using intersectionality theory as our framework, we tested two competing models to determine whether the effects of minority sexual identity (lesbian, bisexual) and race/ethnicity (African American, Latinx, White) are: 1) additive, or 2) multiplicative in the associations between relationship status and heavy drinking.

Methods.

Data are from a diverse sample of cisgender sexual minority women (N = 641) interviewed in Wave 3 of the CHLEW study, a 20-year longitudinal study of SMW’s health.

Results.

Findings from two- and three-way interactions provide mixed evidence for both the additive and multiplicative hypotheses; support for each varied by sexual identity and race/ethnicity. Overall, we found that Latinx SMW, particularly single and bisexual Latinx SMW report the highest rates of heavy drinking compared to their cohabiting and lesbian counterparts, respectively. African American single SMW reported significantly higher rates of heavy drinking compared to their cohabiting counterparts.

Conclusion.

Our findings suggest that the protective qualities of SMW’s intimate relationships vary based on sexual identity and race/ethnicity—and the intersections between them. These results highlight that research among SMW that does not take into account multiple marginalized identities may obscure differences.

Public Significance.

Little research has focused on health within sexual minority women’s relationships, particularly among sexual minority women of color. Given the potential additive or multiplicative effects of multiple sources of oppression such as heterosexism, racism, and sexism, understanding the potential protective effects of relationships is important. Our findings demonstrate that the protective qualities of intimate relationships among SMW vary based on sexual identity and race/ethnicity – and the intersections between them.

Keywords: lesbian women, bisexual women, alcohol use, race/ethnicity, intersectionality, intimate relationships, same-sex couples

INTRODUCTION

Cisgender (individuals whose gender identity is consistent with sex assigned at birth) sexual minority women (SMW; e.g., lesbian, bisexual) are at disproportionately higher risk of heavy drinking compared to cisgender heterosexual women, with bisexual women at higher risk than lesbian women (Cochran & Mays, 2000; Drabble, Midanik, & Trocki, 2005; Hughes, Johnson, Steffen, Wilsnack, & Everett, 2014; Hughes, Szalacha, & McNair, 2010; S. C. Wilsnack et al., 2008). Compared to heterosexual women, SMW are significantly more likely to be current drinkers, heavy drinkers, to report past month binge drinking, and to have an alcohol use disorder (SAMHSA et al., 2016).

Elevated risk of heavy drinking among SMW has been linked to exposure to multiple and chronic stressors, particularly minority stressors (Condit, Kataji, Drabble, & Trocki, 2011; Keyes, Hatzenbuehler, Grant, & Hasin, 2012; McCabe, Hughes, Bostwick, West, & Boyd, 2009). There is a great deal of literature demonstrating that intimate relationships are protective against stress and stress-related health problems in the general population (see Umberson & Montez, 2010 for a review), but very little research has focused on same-sex intimate relationships (Lewis et al., 2015; Reczek, 2012; Reczek, Liu, & Spiker, 2014; Umberson, Donnelly, & Pollitt, 2018). Thus, there is a dearth of research on drinking in the context of SMW’s relationships, and even less is known about relationships and drinking among SMW of color (Lewis et al., 2015; Reczek et al., 2014; Umberson & Montez, 2010).

Relationships and drinking among heterosexuals

For heterosexual couples being in a committed relationship, particularly being married and having children, is associated with better health and health behaviors, including more moderate alcohol use (Fischer & Wiersma, 2012; Hughes et al., 2010; Smith, Homish, Leonard, & Cornelius, 2012; Umberson & Montez, 2010). There are a number of reasons why intimate relationships are associated with improved health and more positive health behaviors. For example, partners may monitor or regulate one another’s health and health behaviors and couples may co-create norms for health behaviors (Reczek, 2012; Reczek & Umberson, 2012; Umberson & Montez, 2010). Being married and having children may also foster a greater sense of responsibility for being healthier (Reczek & Umberson, 2012; Ross & Mirowsky, 2013). Further, relationships increase one’s sense of coherence (i.e., perception that the world is comprehensible, manageable, and meaningful; Antonovsky & Sagy, 1986), which has positive implications for mental and physical health (Reczek, 2012; Reczek & Umberson, 2012; Ross & Mirowsky, 2013; Umberson & Montez, 2010).

Committed relationships provide some protections against heavy drinking among heterosexual women, however, when relationships are strained, risk for problematic drinking increases (Kassel, Stroud, & Paronis, 2003; Umberson & Montez, 2010), in part because relationships are a key part of women’s lives and their identities (Simon & Barrett, 2010; Whitton & Kuryluk, 2014). Further, relationship problems are strongly associated with stress (Horwitz, White, & Howell-White, 1996). Relationship stress or dissolution may increase the risk of unhealthy coping behaviors, such as heavy alcohol use (Hughes, 2011; Kassel et al., 2003; Levitt & Leonard, 2015); conversely, heavy or problematic alcohol use may increase relationship stress and the risk of dissolution (Fischer & Wiersma, 2012; Ostermann, Sloan, & Taylor, 2005).

Relationships and drinking among sexual minority women

Consistent with research among heterosexual women, limited previous research has demonstrated that being married (Reczek et al., 2014) or in a committed relationship (Veldhuis et al., 2019) is protective against heavy drinking among SMW. Most previous research on relationships and alcohol use has relied on partner sex/gender as a proxy for sexual identity (Reczek et al., 2014) because until relatively recently nationally representative datasets did not include questions about sexual identity. This practice precludes the ability to compare SMW who are single or those who identify as sexual minority but who do not have a same-sex partner (e.g., bisexual women in relationships with men) with SMW in committed or married relationships. Research on the associations between heavy drinking and relationship characteristics among SMW has tended to rely on samples composed of primarily young, White, and well-educated women (see for example Lewis, Winstead, Braitman, & Hitson, 2018).

Building on previous research, Veldhuis and colleagues (2019) used data from a diverse sample of SMW in the CHLEW study to examine the associations between relationship status and heavy drinking. Results of this study suggest that, similar to heterosexual women, being in a committed relationship is protective against heavy drinking. Veldhuis and colleagues found that SMW in cohabiting relationships reported drinking lower quantities of alcohol and experiencing fewer alcohol problem consequences and dependence symptoms than single SMW. Bisexual women who were single or in committed relationships, but who were not living with their partners, were more likely to report symptoms of alcohol dependence than bisexual women in committed and cohabiting relationships. Somewhat different findings were reported by Du Bois and colleagues (2019) who used 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data to examine the associations among sexual identity, relationships, and health. They found that lesbian women who were partnered (but not married) had higher rates of heavy drinking than their married, single, divorced/separated/widowed counterparts (Bois, Legate, & Kendall, 2019). Bisexual women were not included and the authors were not able to compare cohabiting and non-cohabiting committed relationships.

Minority stress is believed to be a major contributing factor to SMW’s elevated risk of heavy drinking (Condit et al., 2011; Goldbach, Tanner-Smith, Bagwell, & Dunlap, 2014; Keyes et al., 2012; Matthews et al., 2014; McCabe, Bostwick, Hughes, West, & Boyd, 2010; Meyer, 1995; 2003; Molina et al., 2015). SMW women face unique and chronic stressors (e.g., stigma, discrimination, and internalized homonegativity) related to their marginalized status (Meyer, 1995; 2003). Bisexual women additionally report experiencing prejudice and stereotyping due to perceptions in both heterosexual and sexual minority communities that bisexual women are confused about their sexuality, promiscuous, and/or hyper-sexual (Beach et al., 2018; Bostwick & Hequembourg, 2014; Chmielewski & Yost, 2013; Flanders, Shuler, Desnoyers, & VanKim, 2020; Flanders, Shuler, Desnoyers, & VanKim, 2020; Flanders, Anderson, Tarasoff, & Robinson, 2019). Higher levels of minority stress increase the risk of unhealthy coping behaviors such as heavy drinking (Herek & Garnets, 2007; Hughes, 2011; Keyes et al., 2012; Lewis, Kholodkov, & Derlega, 2012) by overburdening coping resources and impairing emotion regulation (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013). Minority stress in same-sex relationships has also been associated with lower levels of passion and commitment (Doyle & Molix, 2015) and lower levels of relationship satisfaction (Lewis et al., 2012).

Societal attitudes toward same-sex relationships are improving; a recent Gallup poll found that societal support of same-sex relationships has more than doubled since 1996 (Gallup, 2017). However, stigma and homonegativity persist and, when internalized, can have deleterious effects (Frost & Meyer, 2009). SMW who have high levels of internalized bi-or homo-negativity feel less comfortable with their sexual identities. This discomfort can negatively impact intimate relationships (Berg, Munthe-Kaas, & Ross, 2016; Frost & Meyer, 2009; Mohr & Daly, 2008; Otis, Rostosky, Riggle, & Hamrin, 2006) by lowering relationship satisfaction and investment (Barrantes, Eaton, Veldhuis, & Hughes, 2017), and by increasing relationship problems and strain (Frost & Meyer, 2009)—all of which may increase risks within intimate relationships for problematic alcohol use.

Risks may also be heightened among SMW of color. However, examining sexual identity or racial/ethnic differences to the exclusion of potential effects of multiple marginalized statuses can lead to a limited understanding of health risks and protections (Ferguson, Carr, & Snitman, 2014; Lincoln, 2015; Szymanski & Gupta, 2009). Intersectionality accounts for the potential cumulative effects of multiple intersecting forms of oppression such as racism, sexism, and homophobia in shaping an individual’s experience (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a; Ferguson et al., 2014; Lincoln, 2015; Parent, DeBlaere, & Moradi, 2013).

Arguably, using quantitative data—as opposed to qualitative or mixed-methods data—could be an insufficient method for investigating intersectional sources of oppression. Indeed, at the very core intersectionality underscores that the intersections between multiple dimensions of identity and experiences are exceptionally complex. Quantitative methods require that experiences associated with multiple identities be reduced to discrete categories (McCall, 2005) and may thus be too reductionistic to capture the intricacies of intersectional identities. The categorization required for quantitative analyses likely obscures diversity within categories and may paradoxically lead to exclusion and inequality (McCall, 2005). However, given the dearth of research on racial/ethnic minorities within the LGBTQ+ literature and the even more scarce literature investigating how multiple marginalized identities may be associated with wellbeing, it seems as though taking an intercategorical complexity approach to quantitative intersectional research may be of value.

McCall defines intercategorical complexity as an approach in which researchers “provisionally adopt existing analytical categories to document relationships of inequality among multiple and conflicting dimensions” (McCall, 2005). In the current study, the intention of using an intersectional approach in examining the associations between heavy drinking and relationship status is to illuminate the complexities and within-group heterogeneities (M. A. Green, Evans, & Subramanian, 2017) among SMW. Although categories such as sexual identity and race/ethnicity are limited proxies for diverse experiences, quantitative methods provide some tools for understanding of the complexities of experience and can help shed light on multiple determinants of wellbeing. Indeed, as Crenshaw noted “recognizing that identity politics takes place at the site of where categories intersect thus seems more fruitful than challenging the possibility of talking about categories at all” (Crenshaw, 1991).

One key contribution of quantitative approaches to intersectionality is the ability to empirically test competing models, specifically the additive versus multiplicative models. Consistent with the double jeopardy perspective, the additive model suggests that deleterious effects of marginalized identities are independent, and thus the risk of being a woman of color adds to the risk of being a SMW (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a). Race/ethnicity and sexual identity (bisexual compared to lesbian), exert additive effects on outcomes. Much of the research on racial/ethnic differences has taken an additive approach to racial/ethnic differences by focusing on main effects of race/ethnicity. This approach ignores the potential interactions among marginalized statuses (Bowleg, 2008). Thus, consistent with intersectionality theory, the multiplicative model suggests that the combined effects of inequity related to race/ethnicity and sexual identity will be greater than either effect alone and will also be greater than their sum. These effects interact in a multiplicative manner and synergistically exacerbate risks or promote resiliencies.

Intersectionality and heavy drinking.

In the general population, women of color typically report lower levels of heavy drinking than White women (Calabrese, Meyer, Overstreet, Haile, & Hansen, 2015; Witbrodt, Mulia, Zemore, & Kerr, 2014; Zapolski, Pedersen, McCarthy, & Smith, 2014). Cultural, religious, and familial norms related to alcohol use have been found to be protective against heavy drinking among women of color (Zapolski et al., 2014). Among SMW, however, rates of heavy drinking vary less by race/ethnicity (Balsam et al., 2015; Cochran, Peavy, & Robohm, 2007; Grella, Karno, Warda, Moore, & Niv, 2009; Hughes, Matthews, Razzano, & Aranda, 2003; Hughes, Wilsnack, Szalacha, Johnson, Bostwick, Seymour, Aranda, Benson, & Kinnison, 2006b; Matthews et al., 2014; Mereish & Bradford, 2014). These findings suggest that being a racial/ethnic minority may not afford the same protections against heavy drinking for SMW (Cochran, Peavy, & Robohm, 2007; Hughes, Matthews, Razzano, & Aranda, 2002; Matthews et al., 2014; Mereish & Bradford, 2014). Because minority stress heightens SMW’s overall risk of heavy drinking, marginalization related to having a minority race/ethnicity may place SMW of color at additional risk (Bowleg, 2008; Calabrese et al., 2015; Matthews et al., 2014; Mereish & Bradford, 2014; Sutter & Perrin, 2016). Notably, even at lower levels of alcohol use, women of color in the general population experience more alcohol-related problems, social consequences, and illnesses than White women (Witbrodt et al., 2014; Zapolski et al., 2014; Zemore et al., 2018). These findings highlight the need to understand racial/ethnic differences in heavy drinking among SMW. Yet, research on the potential effects of multiple marginalized identities on alcohol use—and whether intimate relationships may provide some protections—is sparse (Lincoln, 2015).

Intersectionality, relationships, and health.

Some research suggests that health in the context of intimate relationships varies by race/ethnicity (Liu, Reczek, Mindes, & Shen, 2016; Umberson, Williams, Thomas, Liu, & Thomeer, 2014) and ostensibly the intersections between race/ethnicity, sex/gender, and sexual identity. There is some evidence that SMW of color are less likely than White SMW or heterosexual women of color to live with their partners. And that among those who do, cohabiting may provide fewer health protective benefits (Battle & DeFreece, 2014; Liu, Reczek, & Brown, 2013). For example, Liu and colleagues (Liu et al., 2013) examined self-rated health by relationship status, sexual identity (as indicated by sex/gender of partner), and race/ethnicity. In contrast to the protective effects of cohabiting relationships for White SMW, single women (of any sexual identity) and non-cohabiting SMW of color may enjoy more health protections than their cohabiting counterparts.

Lower protections among cohabiting SMW of color have been theorized to be associated with higher levels of minority stress and general stress (Liu et al., 2013). Same-sex female couples of color are more likely than White same-sex female couples to have children in the home and to report lower incomes, lower college completion, and higher levels of unemployment—all of which may increase general stress (Reczek et al., 2014). The higher levels of minority stress among SMW of color may be partially due to racism in predominantly White lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) communities (Balsam, Molina, Beadnell, Simoni, & Walters, 2011). Potentially higher levels of stress among cohabiting SMW of color (Liu et al., 2013) may place undue strain on intimate relationships and increase risk of unhealthy behaviors and poor health outcomes (Umberson et al., 2014). However, little empirical research has tested these potential associations.

Current Study

The majority of research on SMW’s problematic alcohol use has centered on individual risk factors; yet, drinking is often social, and is affected by relationships (R. W. Wilsnack, Vogeltanz, Kristjanson, Wilsnack, & Schafer, 2000). Relationships are an important context for understanding problematic alcohol use risks but this is underresearched among SMW. As noted above, SMW of color may experience higher levels of stress, even in committed and cohabiting relationships, underscoring the importance of understanding how risk and protective factors differ for white SMW and SMW of color. Although much less research has focused on bisexual compared to lesbian women, existing evidence shows that they report substantially higher health risk behaviors, including hazardous drinking and poorer mental and physical health outcomes (Bostwick, Boyd, Hughes, & McCabe, 2010; Drabble et al., 2005; Flanders et al., 2020; McCabe et al., 2009; Ramirez & Galupo, 2020; Ross et al., 2018; Salway et al., 2018; S. C. Wilsnack et al., 2008), and that rates and risks may vary by race/ethnicity (Bostwick, Hughes, Steffen, Veldhuis, & Wilsnack, 2018; Flanders et al., 2020; Ghabrial & Ross, 2018; Molina et al., 2015; Ramirez & Galupo, 2020).

Existing research on the associations between intimate relationships and health is limited by absent or inadequate measures of sexual identity and by overreliance on homogenous samples (e.g., well-educated White women). To better understand how sexual identity and race/ethnicity may interact to influence risk of heavy drinking among SMW in varying relationship statuses, we examined data from a large and diverse sample. We tested two competing models to determine whether the effects of minority sexual identity (lesbian, bisexual) and minority race/ethnicity (African American, Latinx) are: 1) additive, or 2) multiplicative in the associations between relationship status and heavy drinking. Based on existing literature we expected that cohabiting might provide fewer protections for SMW of color than for White SMW, and that the associations between race/ethnicity and relationship status would differ for lesbian and bisexual women.

H1.

Consistent with the additive (double jeopardy) perspective, the deleterious effects of multiple marginalized identities are independent, and thus being a woman of color and having a bisexual identity (relative to lesbian identity) add to the risk of being a White SMW (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a). Minority race/ethnicity (African American, Latinx) and bisexual identity will exert additive effects on the association between relationship status and heavy drinking. Support for this hypothesis will be shown by significant discrete effects of race/ethnicity and bisexual identity on the association between relationship status and drinking. This will be tested by conducting separate two-way interactions between race/ethnicity and relationship status and sexual identity and relationship status on drinking quantity.

H2.

Conversely, consistent with intersectionality theory (multiplicative), the combined effects of marginalization/inequity related to minority race/ethnicity and bisexual identity will be greater than either effect alone and greater than their sum. These effects will interact in a multiplicative manner and will synergistically exacerbate risk of heavy drinking for SMW who are not in committed and cohabiting relationships. Support for this hypothesis will be demonstrated by significant interaction effects between race/ethnicity and sexual identity on the association between relationship status and heavy drinking. This will be tested with a three-way interaction between race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and relationship status.

METHODS

Data Source

The Chicago Health and Life of Women (CHLEW) study was designed to replicate and extend the National Study of Health and Life Experiences of Women (NSHLEW), a 20-year longitudinal study of alcohol use among women in the general U.S. population (R. W. Wilsnack, Kristjanson, Wilsnack, & Crosby, 2006; S. C. Wilsnack, Klassen, & Wilsnack, 1984). To date, CHLEW researchers have collected three waves of data from women recruited in the greater Chicago metropolitan area (Everett, Hatzenbuehler, & Hughes, 2016a; Hughes et al., 2006); a fourth wave of data collection is nearly completed. The CHLEW survey includes a broad range of questions related to drinking behaviors and drinking-related problems, physical and mental health, and a variety of life experiences—with particular focus on women’s relationships. Each wave of the study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at the PI’s (T.L. Hughes) academic institution.

Sample

In 2000-01, 447 women ages 18 years or older, all of whom self-identified as lesbian were recruited from Chicago and the surrounding suburbs using social network and snowball sampling methods and interviewed as part of the baseline study. Data for Wave 2 of the CHLEW were collected in 2004-2005 with 384 women (response rate = 86%), and for wave 3 in 2010-12 with 354 women (response rate = 79%). In wave 3 a supplemental sample of younger women (ages 18-25), Black/African American (hereafter we will use the term African American) women, Latinx women, and bisexual women (N = 372) was recruited using a substantially modified version of respondent-driven sampling (Martin, Johnson, & Hughes, 2015). The current study uses wave 3 data only, which includes 353 participants from the original cohort and 372 participants from the wave 3 supplemental sample (N = 725). Data from participants who identified as heterosexual (n = 6), mostly heterosexual (n = 8), other sexual identity (n = 7; six of whom identified as queer and one as “open”) were excluded, as were those with missing data for sexual identity (n = 1). Participants who did not indicate their relationship status (n = 31) and those who reported their race/ethnicity as anything other than African American, Latinx, or White (n = 28) were also excluded from analyses. Women who reported that they were currently in different-sex relationships (one-half of bisexual women [n = 81] and a small minority of lesbian women [n = 22]) were included in the current study. The few participants who identified as transgender (n = 4) were excluded as the focus of the larger longitudinal study is on cisgender SMW. Women who have never consumed alcohol were also excluded, resulting in an analytic sample of 641 SMW.

Measures

Sexual identity.

Participants were asked if they self-identified as exclusively lesbian, mostly lesbian, bisexual, mostly heterosexual, exclusively heterosexual, transgender, or other. As described above, only women who identified as lesbian (exclusively and mostly categories combined) or bisexual were included in the current study. Of note, at the time of the study identities such as asexual and queer as well as more nuanced measures of plurisexual identities (e.g., pansexual) were less commonly used and even less commonly measured. Further, although we recognize that gender identity and sexual identity are two separate identities, at the time the CHLEW study was designed it was common to include a response option of transgender in questions about sexual orientation.

Race/ethnicity.

Race/ethnicity was determined based on two questions asking participants to indicate their race and whether they were of Hispanic or Latina origin or descent. Responses were categorized into White, African American, and Latinx (a gender-neutral term for people of Latin American descent or origin) racial/ethnic groups.

Relationship status.

Participants indicated whether they were: not in a committed relationship (single), in a committed relationship but not living together (not cohabiting), or in a committed relationship and living together (cohabiting). Because same-sex marriage or civil unions were not yet legal in [state] when data collection for wave 3 began, there were insufficient numbers of women who reported being married or in a civil union (n = 60) to include this relationship status as a separate category. Previous research has found no significant differences in alcohol outcomes between same-sex female couples who are married and those in cohabiting relationships (Reczek et al., 2014). We compared CHLEW participants who reported being married and those who reported being in committed relationships and living with their partner and found no significant differences on any drinking outcome (data available upon request). Therefore, all cohabiting women, regardless of legal status, were combined in all analyses.

Drinking Quantity.

Although there are a number of ways of capturing drinking behavior, quantity of drinking is associated with increased health risks and dependency and is thus the drinking outcome for this study. Participants were asked to indicate the average number of alcoholic drinks they consumed in a typical day when they consumed alcohol in the past month (continuously measured; range 0-24 drinks).

Covariates.

Covariates included age (30 or under; 31-40; 41-50; 51 or older), education (< high school; high school; some college; bachelor’s degree; graduate/professional degree), employment (full-time; part-time; unemployed-looking; unemployed-not looking), and whether or not there were children living in the home (yes; no). In a study using National Health Interview Study data, Hsieh and Liu (Hsieh & Liu, 2019) found no differences in self-rated health or functional limitations among bisexual women by relationship status. However, differences were found when bisexual individuals’ partner sex/gender was taken into account; bisexual individuals in same-sex/gender relationships reported significantly better self-rated health and fewer functional limitations than their counterparts in different sex/gender relationships. Thus, in the current study, we adjusted for partner sex/gender (woman; man).

Data analysis

ANOVAs were used to examine differences by sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and relationship status in past 30-day drinking quantity. General linear modeling was used to test the interaction between race/ethnicity and sexual identity. To test whether the effects of race/ethnicity and sexual identity were additive (i.e., whether they exerted independent effects in the association between relationship status and drinking quantity), general linear modeling was used to examine the interactions of sexual identity and race/ethnicity with relationship status (i.e., sexual identity X relationship status, race/ethnicity X relationship status) on the drinking quantity outcome. Significant interactions of race/ethnicity or sexual identity with relationship status on the drinking quantity outcome provide support for the additive hypothesis (Richardson & Brown, 2016).

To test the multiplicative hypothesis, the combined effects of minority race/ethnicity and sexual identity on the associations between relationship status and drinking quantity were tested to determine whether the interactions were greater than either effect alone—and greater than their sum. The second set of models additionally tested the three-way interactions among sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and relationship status. A three-way interaction term (sexual identity X race/ethnicity X relationship status) was added to the additive models. Significant interaction effects among race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and relationship status were considered to support the multiplicative hypothesis. Main effects were included in interaction models, but were not interpreted as they may not be meaningful (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016b; Richardson & Brown, 2016). Stratified analyses included two-way interactions between sexual identity and race/ethnicity separately with relationship status to decompose the three-way interaction results.

Conducting intersectional analyses using this method has a key limitation: the inclusion of lower-order main effects in the model may decrease the probability of finding significant higher-order interaction effects, as main effects may explain some of the variance in the outcomes (Rouhani, 2014; Scott & Siltanen, 2012). To address this, alpha was increased to p < .10 to evaluate the interactions only; all other analyses used p < .05.

For each of the aforementioned analyses, we tested each model first without covariates to examine unadjusted associations and then with covariates (i.e., age, education, employment status, and children in the home). All analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) statistical software.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 presents a summary of the demographic characteristics of the sample by sexual identity and race/ethnicity. Compared with lesbian women, bisexual women were younger, more likely to have children in the home, less likely to be employed full-time, more likely to have a high school education or less, and more likely to be single. Compared with White women, both African American and Latinx women reported lower levels of education, were less likely to live in committed cohabiting relationships, and were more likely to be in noncohabiting relationships or to be single. African American women were less likely to be employed full-time and more likely to have children in the home than Latinx or White women. Latinx women were more likely than African American or White women to be age 30 or younger.

Table 1.

Demographics by sexual identity and race/ethnicity (N = 641).

| TOTAL (N = 641) | African American (n = 239) | Latinx (n = 154) | White (n = 248) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesbian | Bisexual | Lesbian | Bisexual | Total | Lesbian | Bisexual | Total | Lesbian | Bisexual | Total | |

| Relationship status | |||||||||||

| Cohabiting | 43.9% | 23.6% | 34.5% | 12.3% | 28.5% | 40.7% | 19.5% | 35.1% | 54.4% | 39.0% | 50.8% |

| Noncohabiting | 21.2% | 26.7% | 27.0% | 26.2% | 26.8% | 20.4% | 36.6% | 24.7% | 16.4% | 20.3% | 17.3% |

| Single | 34.9% | 49.7% | 38.5% | 61.5% | 44.8% | 38.9% | 43.9% | 40.3% | 29.1% | 40.7% | 31.9% |

| Age | |||||||||||

| 30 or less | 28.2% | 47.9% | 25.9% | 38.5% | 29.3% | 40.7% | 56.1% | 44.8% | 22.8% | 52.5% | 29.8% |

| 31-40 | 19.7% | 26.1% | 19.5% | 26.2% | 21.3% | 23.9% | 19.5% | 22.7% | 17.5% | 30.5% | 20.6% |

| 41-50 | 20.4% | 14.5% | 26.4% | 15.4% | 23.4% | 17.7% | 17.1% | 17.5% | 16.4% | 119% | 15.3% |

| 51 or more | 31.7% | 11.5% | 28.2% | 20.0% | 25.9% | 17.7% | 7.3% | 14.9% | 43.4% | 5.1% | 34.3% |

| Education | |||||||||||

| < High school | 6.1% | 13.9% | 12.6% | 18.5% | 13.9% | 4.4% | 24.4% | 11.2% | 1.1% | 1.7% | 1.1% |

| High school | 11.8% | 16.4% | 20.1% | 26.2% | 21.8% | 12.4% | 22.0% | 14.3% | 3.7% | 1.7% | 3.1% |

| Some college | 31.5% | 30.3% | 39.7% | 33.8% | 37.3% | 34.5 % | 34.1% | 34.8% | 22.2% | 23.7% | 23.0% |

| College graduate | 21.6% | 20.0% | 13.8% | 13.8% | 15.1% | 23.0% | 7.3% | 18.6% | 28.0% | 35.6% | 28.7% |

| Graduate school | 29.0% | 19.4% | 13.8% | 7.7% | 11.9% | 25.7% | 12.2% | 21.1% | 45.0% | 37.3% | 44.1% |

| Employment | |||||||||||

| Full time | 52.9% | 40.0% | 38.5% | 34.5% | 37.7% | 64.6% | 36.6% | 57.1% | 59.3% | 47.5% | 56.5% |

| Part time | 17.2% | 17.0% | 16.7% | 12.3% | 15.5% | 17.7% | 17.1% | 17.5% | 17.5% | 22.0% | 18.5% |

| Unemployed-looking | 13.7% | 26.7% | 23.0% | 30.8% | 25.1% | 11.5% | 34.1% | 17.5% | 6.3% | 16.9% | 8.9% |

| Unemployed-not looking | 16.2% | 16.4% | 21.8% | 21.5% | 21.8% | 6.2% | 12.2% | 7.8% | 16.9% | 13.6% | 16.1% |

| Children in the home | |||||||||||

| No | 81.3% | 77.6% | 71.0% | 69.2% | 71.3% | 85.8% | 78.0% | 83.8% | 86.4% | 86.4% | 87.1% |

| Yes | 18.7% | 22.4% | 29.0% | 30.8% | 28.7% | 14.2% | 22.0% | 16.2% | 13.6% | 13.6% | 12.9% |

| Sex/gender of partner | |||||||||||

| Woman | 95.4% | 49.3% | 95.3% | 54.2% | 84.6% | 94.3% | 43.2% | 81.1% | 96.2% | 47.9% | 86.1% |

| Man | 4.6% | 50.7% | 4.7% | 45.8% | 15.4% | 5.7% | 56.8% | 18.9% | 3.8% | 52.1% | 13.9% |

Drinking quantity and associations with sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and relationship status.

Sexual identity.

There were significant unadjusted sexual identity differences in drinking quantity, F (1, 639) = 10.275, p < .01. Bisexual women reported a significantly higher average number of drinks per day on the days they consumed alcohol (drinking quantity; M = 3.93, SD = 4.72) than lesbian women (M = 1.97, SD = 1.74). However, this main effect was attenuated when covariates were added to the model, F (1, 542) = 3.795, p = .052.

Race/ethnicity.

There were significant differences in average number of drinks per day by race/ethnicity, F (2, 639) = 7.50, p < .01, controlling for covariates. Planned comparisons revealed that Latinx SMW (M = 2.88, SD = 3.09) reported drinking significantly higher quantities of alcohol than White (M = 1.70, SD = 1.35; p < .001) and African American (M = 2.13, SD = 2.12; p < .01) SMW.

Relationship status.

There were significant adjusted differences in drinking quantity by relationship status, F (2, 639) = 3.65, p < .05. Planned comparisons revealed that single SMW (M = 2.48; SD = 2.85) reported drinking significantly higher quantities than cohabiting SMW (M = 1.86; SD = 1.68), but there were no significant differences between non-cohabiting (M = 2.02; SD = 1.70) SMW and cohabiting SMW.

Interaction between sexual identity and race/ethnicity

There was a significant unadjusted interaction between sexual identity and race/ethnicity, F (1, 592) = 3.30, p < .05. However, this association was no longer significant when covariates were added to the model, F (2, 592) = 1.80, ns.

Additive Hypothesis: Effects of sexual identity and race/ethnicity separately

The interaction between sexual identity and relationship status on drinking quantity was not significant. There were significant adjusted associations in the interactions between relationship status and race/ethnicity, F (4, 592) = 3.28, p < .05 on drinking quantity. Follow-up comparisons indicated that among single women, Latinx SMW drank significantly higher quantities than White and African American SMW. Among SMW in committed cohabiting relationships, Latinx SMW reported drinking significantly higher quantities of alcohol than White SMW. African American cohabiting SMW drank significantly higher quantities of alcohol than their White cohabiting counterparts, however there was no significant difference between cohabiting African American and Latinx SMW.

Among Latinx SMW, single SMW reported drinking significantly higher quantities than their cohabiting counterparts. There were no significant differences among African American SMW based on relationship status. Among White SMW cohabiting women reported significantly lower drinking quantities than their non-cohabiting and single counterparts. See Table 2 for means and standard deviations.

Table 2.

Average drinking quantity and standard deviations by sexual identity and race/ethnicity

| TOTAL (N = 641) | African American (n = 239) | Latinx (n = 154) | White (n = 248) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Lesbian women (n = 476) | ||||||||

| Cohabiting | 1.82 | 1.47 | 2.42e,1 | 1.93 | 2.04f,2 | 1.04i | 1.381,2 | 1.16 |

| Noncohabiting | 1.91 | 1.55 | 1.87 | 1.73 | 2.20 | 1.54 | 1.77 | 1.25 |

| Single | 2.12 | 2.03 | 1.63e,3 | 1.52 | 3.10f,3,4 | 2.85i | 1.944 | 1.46 |

| Bisexual women (n = 165) | ||||||||

| Cohabiting | 2.030 a | 2.52 | 1.56 | 3.17 | 3.11 | 3.79 | 1.77 | 1.34 |

| Noncohabiting | 2.32 | 2.03 | 2.24 | 2.46 | 2.31 | 1.89 | 2.57 | 1.13 |

| Single | 3.25 a | 4.02 | 3.205 | 2.88 | 5.115,6 | 6.47 | 1.586 | 1.43 |

| Total | ||||||||

| Cohabiting | 1.86 b | 1.68 | 2.307 | 2.12 | 2.21g,8 | 1.78h,j | 1.457,8 | 1.20 |

| Noncohabiting | 2.02 c | 1.70 | 1.97 | 1.94 | 2.24 | 1.66h | 1.92 | 1.26 |

| Single | 2.48 b,c | 2.85 | 2.189 | 2.22 | 3.71g,h,9,10 | 4.33j | 1.8410 | 1.45 |

NOTE: Letters denote significant pairwise comparisons in columns; numbers represent significant pairwise comparisons in rows. All significant pairwise comparisons were significant at p < .05.

Multiplicative Hypothesis: Interactions between sexual identity and race/ethnicity

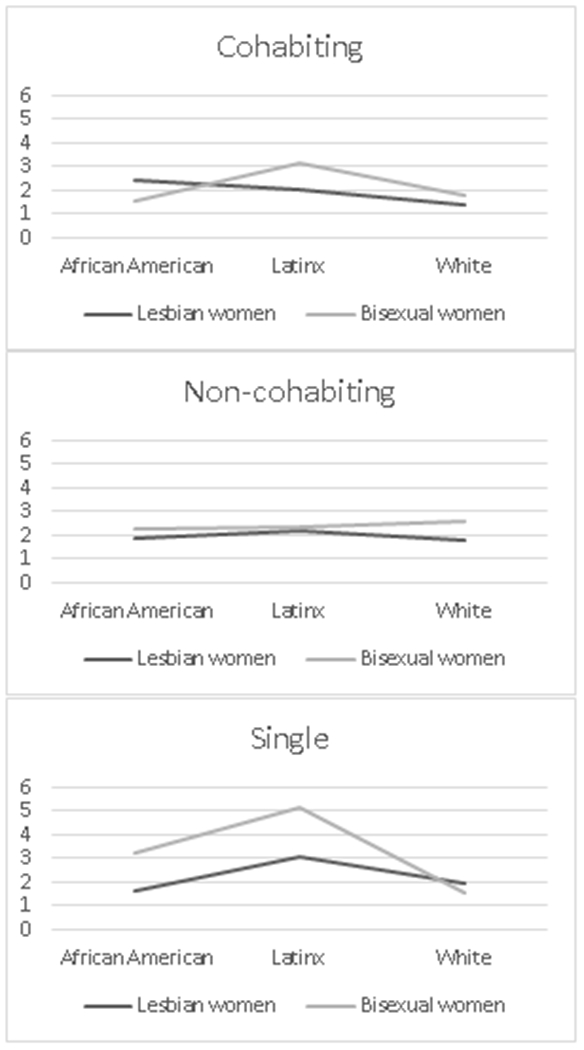

There was a significant three-way interaction among sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and relationship status on drinking quantity, F (4, 521) = 2.035, p < .10. To follow-up on the significant three-way interaction, stratified models were first tested by sexual identity to examine potential differences in drinking quantity by race/ethnicity and relationship status, and the interaction between them on drinking quantity (see Figure 1). Among lesbian women, single Latinx lesbian women reported drinking significantly higher quantities than single White and African American lesbian women and higher quantities than Latinx lesbian women in cohabiting relationships. Among bisexual women, single Latinx and African American women reported drinking significantly more than single White SMW.

Figure 1.

Drinking quantity by relationship status and race/ethnicity with separate lines for sexual identity (lesbian, bisexual).

The models were then stratified by race/ethnicity. Among Latinx women, single bisexual women reported drinking significantly more than single lesbian women and more than cohabiting bisexual women. Latinx single lesbian women also reported drinking greater quantities than their Latinx cohabiting counterparts. Among African American women, single bisexual women reported drinking significantly higher quantities than single lesbian women. Single lesbian women reported drinking significantly higher quantities than their cohabiting counterparts. Among White women, single lesbian women reported drinking significantly higher quantities than their cohabiting counterparts. There were no differences among bisexual women.

Discussion

We aimed to understand whether the risk of heavy drinking among SMW of color was additive or multiplicative. Relatively few studies of SMW’s health have the sample size and representation of SMW of color to examine racial/ethnic differences, much less to test how race/ethnicity and sexual identity interact to influence health behavior (Bowleg, 2008; Eagly, Eaton, Rose, Riger, & McHugh, 2012; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a). Because SMW, particularly those who are also racial/ethnic minorities, live within a context of multiple forms of oppression, using an intersectional framework is important for understanding the complex factors related to alcohol use (Lincoln, 2015). By testing and comparing the prevailing main effects method of examining racial/ethnic differences (i.e., the additive model) and the interactive/multiplicative model, this study makes a strong contribution towards understanding the associations between multiple marginalized identities and heavy drinking.

Testing competing models of intersectionality.

One of the challenges in doing intersectionality research is that the findings can be complex and difficult to interpret (McCall, 2005). Indeed, the findings of this study provide mixed evidence for both the additive and multiplicative hypotheses, and support for each varied based on sexual identity and race/ethnicity. Consistent with the double jeopardy perspective we hypothesized that the deleterious effects of marginalized identities would be independent or additive. That is, the risk of being a woman of color adds to the risk of being an SMW (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a). In support of the double jeopardy hypothesis, we found higher rates of heavy drinking for Latinx women and that rates of heavy drinking differed by relationship status. Consistent with the intersectionality perspective, and in support of the multiplicative hypothesis, we found rates of heavy drinking varied by the intersections between race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and relationship status.

Latinx SMW.

Our findings of heavier drinking among Latinx SMW compared to White SMW suggest that they may face higher levels of stress from being both Latinx and a SMW (Cerezo & Ramirez, 2020). Slater and colleagues (2017) found that among sexual minorities who reported frequent discrimination, Latinx participants were more likely than non-Latinx participants to report a substance use disorder (Slater, Godette, Huang, Ruan, & Kerridge, 2017). However, the researchers did not examine differences by sex/gender or the interactions among race/ethnicity, sex/gender, and sexual identity. Immigration status was not included in the current study; however, previous research suggests that the xenophobia and discrimination experienced by Latinx SMW who are immigrants may have negative effects on mental health and substance use outcomes (Cerezo, 2016). Higher levels of acculturation have also been associated with higher risk of substance use among Latinx SMW (Matthews et al., 2014).

Sexual minorities of color who are bisexual or non-monosexual may experience discrimination, biphobia, and microaggressions not just from heterosexuals but also from the LGBTQ community (Balsam et al., 2011; Lim & Hewitt, 2018). Recent research suggests that lesbian and gay Latinx individuals may have negative perceptions of bisexual individuals (Dyar, Lytle, London, & Levy, 2017), which could lead to more biphobia within the Latinx LGBTQ community. It is possible that such additional stressors put Latinx SMW, particularly bisexual Latinx women, at higher risk of heavy drinking (Cerezo & Ramirez, 2020). More research is needed to examine the specific associations between stress and alcohol use among Latinx SMW.

Another possible explanation for the higher drinking quantities among cohabiting Latinx SMW compared to cohabiting White SMW may be the level of sexual orientation disclosure. In same-sex relationships overall, chronic concealment of sexual identity carries high risk to both individuals and couples, and can cause significant relationship stress (Clausell & Roisman, 2009; Mohr & Daly, 2008). Being part of a same-sex cohabiting couple makes it more difficult to conceal minority sexual identity (LeBlanc, Frost, & Wight, 2015). However, couples who are not “out” have lower support and higher stress due to the secrecy of their relationship and constant vigilance about others’ perceptions (Green, 2004; Otis et al., 2006). Concealment may cause one or both members of the couple to devalue the relationship, which may reduce relationship satisfaction and investment (Lau, 2012). Conversely, disclosure of sexual identity appears to be associated with improved relationships, social support, and psychological health (Lewis et al., 2012).

Despite the known benefits of disclosure on mental health outcomes, in contexts where SMW may fear rejection due to their sexual identities or experience high levels of homophobia, concealing sexual identity may be adaptive. For example, concealing sexual identity may reduce exclusion or discrimination and may support access to benefits afforded those with non-stigmatized identities (Camacho, Reinka, & Quinn, 2019). Further, in a study comparing White and Latinx gay men, only White men reported improvements in well-being following verbal disclosure of their sexual identities (Villicana, Delucio, & Biernat, 2016). The association between verbal disclosure and well-being was mediated by feelings that being out was important to self-expression and relationships. These associations did not hold among Latinx gay men in the study—verbal disclosure was not associated with self-expression, nor did they feel it was important in their connection with others. Sexual minorities of color may also perceive greater stress from the pressure to come out possibly due to the concomitant pressures from the broader LGBTQ community that equates outness with authenticity and concerns that coming out might threaten familial or community relationships (Ghabrial, 2017). These findings suggest that being out has different meaning and value for White gay men compared to Latinx gay men. More research is needed to examine these associations among SMW.

It is possible that disclosing one’s sexual identity may have different meanings and associations for Latinx and White SMW and may possibly harm or threaten some relationships—or at least not improve relationships (Muñoz-Laboy et al., 2009). As suggested above, being out may expose Latinx SMW to higher levels of stigma and discrimination. In analyses using waves one and two of the CHLEW, Latinx SMW were significantly less likely than White or African American SMW to be out to their families, which the authors theorized might be due to reluctance to threaten familial relationships by disclosing identity (Aranda et al., 2015)]. This may partially explain why cohabiting does not seem to provide the same protections for Latinx SMW and White SMW, as being in a same-sex cohabiting relationship makes sexual identity less concealable. Further, as discussed in the introduction, same-sex female couples of color are more likely to have children living in the home, to have lower levels of education, lower levels of employment, and lower incomes—all of which likely add stress in same-sex female couples of color (Reczek et al., 2014).

African American SMW.

We found no differences between African American SMW and White SMW in associations between cohabiting and drinking. Given that in the general population, African American women drink at lower levels than White women, our null findings suggest that the protection provided by relationships among African American women in the general population may not be the same for African American SMW. Further, our findings suggest that for African American SMW, specifically being in a committed cohabiting relationship confers no additional protections against heavy drinking. Together our findings can be interpreted in at least three ways: 1) for African-American SMW, being a sexual minority may be a more important predictor of heavy drinking than being African American; 2) similar to our discussion above about Latinx SMW’s risks for heavy drinking, there are other important unmeasured predictors of differences in African American SMW’s drinking, such as stress and level of sexual identity disclosure; and 3) given the excess stress that African American SMW face, “positive intersectionality” (Ghabrial, 2017) suggests that similar levels of drinking is a sign of resiliency or psychological strength (Dyar et al., 2019; Ryff, Keyes, & Hughes, 2003).

Another possible explanation for the few differences by sexual identity or relationship status among African American SMW may be that social support provides buffers that mitigate differences in risk associated with bisexual identity (Flanders et al., 2020) or non-cohabiting relationship status. A recent study on resilience among African American lesbian, gay and bisexual emerging adults highlighted the importance of social support from both families and friends in buffering risk of depressive symptomatology (Garrett-Walker & Longmire-Avital, 2018). Identity salience and connectedness to the LGBTQ and African American communities may also provide buffers outside of intimate relationships (Lee, 2018). Indeed, Garrett-Walker and Longmore-Avital’s (2018) findings suggest that support from both family and friends may enhance African American LGBTQ individuals’ acceptance of their multiple identities, which may protect against heavy drinking. African American SMW may also develop coping strategies that are unique to their intersecting identities, such as selective disclosure of their sexual identity and gender non-conformity, that improve resilience (Follins, Walker, & Lewis, 2014). However, our findings suggest that being single may confer additional risks for African American women’s alcohol use. More research is needed to understand single African American SMW’s higher drinking levels. One possible reason for this may be the effects of racism within the LGBTQ community (Balsam et al., 2011) that may disproportionately affect single/dating African American SMW. Another potential reason may be that single African American SMW might experience lower overall levels of social support due to not having a partner.

There may be other factors not accounted for in the current study that may influence associations between relationships, race/ethnicity, and heavy drinking. For example, religion, family, and community may be highly interconnected for some SMW and if the religious community is not LGBTQ affirming it may be a source of disapproval and rejection (Lefevor et al., 2019). This can create tensions and stressors for SMW and may impact their outness (Ghabrial, 2017), their relationships, and their senses of themselves as sexual minorities (Szymanski & Carretta, 2019)—all of which may have implications for their drinking and other health behaviors. Contrastingly, for SMW who belong to more LGBTQ-affirming religious communities, religion and spirituality may provide protections against heavy drinking and may provide important sources of support (Ghabrial, 2017; Lefevor et al., 2019; Lefevor, Park, & Pedersen, 2018).

Notably, the data used in this study were collected before marriage was legal in [state] and before it was legal nationally. More research is needed to understand whether these positive policies may not solely provide legal and social protections for same-sex couples, but also whether the right to marry as well as actually being legally married may be associated with health and health behavior improvements (Drabble et al., 2020). Further, there is some data to suggest that the legalization of marriage may have specific health and wellbeing benefits for SMW of color (Everett, Hatzenbuehler, & Hughes, 2016b), thus this is an important area for future research.

Effects of partner sex/gender.

Given that our previous research showed no effects of partner sex/gender on the associations between relationship status and heavy drinking we initially tested models without partner sex/gender (Veldhuis et al., 2019). Further, because identity is particularly salient in relation to risk of alcohol-related problems among women above and beyond the sex/gender of their partner (Midanik, Drabble, & Trocki, 2007), we anticipated that partner sex/gender would not be important. However, recent research suggests that partner sex/gender may be an important relationship-related variable (Hsieh & Liu, 2019). For example, bisexual-identified women in different-sex relationships appear to experience more minority stress (Dyar, Feinstein, & London, 2014; Feinstein, Latack, Bhatia, Davila, & Eaton, 2016; Herek, 2002; Molina et al., 2015). Thus, we added this variable into the models. Interestingly, the main effect of sexual identity and the interaction between sexual identity and relationship status, as well as the interaction between sexual identity and race/ethnicity on drinking quantity, disappeared. However, the interaction between race/ethnicity and relationship status on drinking quantity remained. Also, the three-way interaction among sexual identity, race/ethnicity and relationship status strengthened. This suggests that partner sex/gender may account for sexual identity differences in heavy drinking and in the associations between sexual identity and relationship status on drinking quantity. More research is needed to understand the associations between partner sex/gender on heavy drinking among SMW.

Practice implications.

Our findings suggest multiple implications for practice. First, clinicians should include the assessments of drinking behaviors as a part of routine clinical practice. Second, addressing drinking behaviors as part of couples’ counseling, or by including the partner in therapy, may improve the efficacy of interventions. In forming relationships, some people seek out and choose partners who are similar to themselves (Wiersma-Mosley & Fischer, 2016). Individuals who partner with similar others are less likely to change; if one of the similarities is drinking behaviors, members of the couple may mutually reinforce the other’s drinking behaviors (Wiersma-Mosley & Fischer, 2016). If both drink heavily, this drinking pattern may be reinforced through the relationship. Among individuals who choose dissimilar partners one member of the couple may influence the other member’s drinking through sharing emotions (e.g., mood contagion) or socialization processes (Reczek, Pudrovska, Carr, Thomeer, & Umberson, 2016; Wiersma-Mosley & Fischer, 2016). Couples-based interventions that take into account the health behaviors of both members of the couple and take advantage of couples’ desires to support each other’s health have been highly successful among smokers (Rodriguez & Derrick, 2017), but to our knowledge couples-based interventions for SMW have not yet been tested for heavy drinking.

Third, clinicians should understand that outness may not be protective for all SMW. Providers working with SMW of color should be aware that although there is some cultural pressure for LGBTQ people to come out and a fairly ubiquitous sense that outness is indicative of being healthier or more authentically LGBTQ+, there may be tensions between this and SMW’s families, communities, religion, and culture. Further, given that differential levels of outness within a relationship can potentially put strain on the more out partner and on the relationship, SMW who are not out may feel additional pressure to disclose their identity from their partner. Clinicians should help SMW talk about how disclosure-related concerns may be affecting the couple’s relationship and help couples work towards their own unique solutions to these competing pressures.

Finally, our findings that the sex/gender of the partner may be an important factor in bisexual women’s alcohol use suggests that clinicians should help bisexual women talk about tensions they may feel between identifying as bisexual and the sex/gender of their participant. More positive bisexual-identity-related experiences in bisexual women’s interpersonal relationships has been associated with better mental health outcomes (Dyar & London, 2018). This suggests that clinicians should help couples (irrespective of sex/gender composition of the couple) overcome barriers to acceptance of each other’s sexual identities—this may be particularly important among couples in which identities are discordant (e.g., a bisexual woman and a heterosexual man; a bisexual woman and a lesbian woman). Bisexual women in relationships with men (perhaps particularly men who identify as heterosexual) may feel less connected to the LGBTQ community, which may lead to isolation and stress. Conversely, bisexual women who feel more connected to the LGBTQ community may experience higher levels of biphobia. Exploring the seeming tensions between the gender composition and sexual identities of the couple would be important in therapy.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when evaluating the results of this study. The sample was originally limited to SMW living in the Chicago metropolitan area. Although some women have moved to geographically distinct areas since they were recruited, the sample is not geographically diverse. Participant recruitment used non-probability methods, which limits generalizability. However, non-probability samples are important for LGBTQ health research as larger and more diverse samples of LGBTQ people can be recruited. Participants may additionally be more open and disclose more in studies by and about LGBTQ people. Non-probability studies are also more likely to include measures germane to LGBTQ health and wellbeing (Henderson, Blosnich, Herman, & Meyer, 2019).

The original study specifically recruited women who identified as lesbian in the first wave, and in wave 3 specifically recruited women who identified as bisexual. Until relatively recently few studies included bisexual women and measurement of plurisexual identities tended to solely focus on bisexual identity (Flanders et al., 2020). Much has changed in that short period of time and the measurement of plurisexual identities in the current study may obscure important differences in associations between relationships, sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and drinking quantity. For example, there is emerging data to suggest that among women who identify as non-monosexual, there may be differences in rates of violence comparing bisexual women to women who identify as other plurisexual identities (Flanders, Anderson, Tarasoff, & Robinson, 2019).

The CHLEW focuses on cisgender sexual minority women, thus findings may or may not extend beyond this population. In particular, it is not clear if these findings extend to transgender and nonbinary individuals who may identify as SMW. This is an important area for future research as rates of heavy drinking among transgender individuals are difficult to estimate given the heterogeneity of samples, methods, and measurement (Gilbert, Pass, Keuroghlian, Greenfield, & Reisner, 2018). Some studies on drinking suggest that almost half (47-48%) of all transgender individuals report heavy drinking, (Herrera et al., 2016; Kerr-Corrêa et al., 2017) whereas other studies (Blosnich, Lehavot, Glass, & Williams, 2017; Coulter et al., 2015) report no differences in heavy drinking or other alcohol-related outcomes between trans- and cisgender participants. Although there has been some literature on the unique stresses and strains of transgender couples, to our knowledge apart from research on HIV and sexual behaviors, little research has examined health and health behaviors within transgender relationships, thus this is an important area for future research.

Because our analyses used cross-sectional data, causality and temporality could not be determined. It is possible, for example, that women who drink heavily are less likely to be in committed or cohabiting relationships. However, previous research has suggested that although heterosexual men who are heavy drinkers are far less likely to be in committed relationships, there is no association between heavy drinking and the likelihood of being in a relationship among heterosexual women (Fischer & Wiersma, 2012). Research using longitudinal data is needed to determine if heavy drinking has a similar association with the likelihood of being in a committed relationship among SMW. Longitudinal research would also support the investigation of changes in relationship status, other relationship factors, and drinking behaviors.

In the current study, we used multiple marginalized identities as proxies for multiple sources of oppression. That is, our analyses assumed that, for example, the identity of being an African American woman was equivalent to the processes and effects of discrimination and racism faced by African American women in U.S. society (Bauer, 2014). However, the intersections among oppression/marginalization related to race/ethnicity, sex/gender, and sexual identity are complex. More research, perhaps particularly qualitative research, is needed to better understand the effects of social processes and inequities on health behaviors within the context of intimate relationships. Quantitative research that takes into account multiple sources of marginalization (e.g., racism, homophobia), multiple sources of stress (e.g., minority stressors, relationship stress), and identity centrality (Lee, 2018) is also needed. Future research should additionally include heterosexual comparison groups to better understand the intersections between race/ethnicity and minority sexual identity.

Despite the diversity of the sample, this study is limited by the inability to include Asian or Native American/Alaska Native SMW as discrete racial/ethnic comparison groups given the low number of participants in the CHLEW study. Asian and Native American/Alaska Native LGBTQ individuals are underrepresented in research. Recent research suggests that relationships provide sizable protections against depression for Asian LGBTQ individuals, highlighting an important need for further research on the role of relationships in health among Asian LGBTQ individuals (Leung, Cheung, & Luu, 2018). Despite these limitations, this study makes an important contribution to understanding the role of intimate relationships among SMW. In particular, it increases understanding of how the potential protective effects of relationship status may differ based on race/ethnicity and sexual identity–and the intersections between these minority statuses.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that the protective qualities of intimate relationships among SMW vary based on sexual identity and race/ethnicity – and the interactions between them. More specifically, our findings support previous literature demonstrating that intimate relationships provide some protection for SMW women of color, but not to the same degree as for White women. More research is needed to understand the reasons for this.

Broadly, our findings suggest that research among SMW that does not take into account intersections between identities may obscure differences. This amplifies the need for researchers to take steps to increase the diversity of their samples (Cerezo, 2020; Ghabrial & Ross, 2018), and to not aggregate analyses across groups (e.g., sex/gender, sexual identity, race/ethnicity). Research using diverse samples can support the examination of intersecting sources of oppression, or at the very least afford the ability to examine sexual identity and racial/ethnic differences to help better understand the diverse needs, strengths/resiliencies, and disparities in the LGBTQ+ community.

Findings from this study have clear implications for understanding alcohol-related disparities among SMW by illuminating populations at highest risk. Uniquely we found that although African American SMW report similar levels of heavy drinking compared to White SMW, and significantly lower levels compared to Latinx SMW, single African American bisexual and lesbian women may be at unique risk for heavy drinking. Further, Latinx SMW, particularly bisexual and single Latinx women, appear to drink the highest quantities of alcohol. Thus, interventions should target these high-risk groups. Previous studies have found that Latinx women have the highest unmet need for treatment compared to White and African American SMW (Jeong, Veldhuis, Aranda, & Hughes, 2016). Even if Latinx and African American SMW wish to obtain treatment, they may experience barriers to care related to stigma, discrimination, or lack of culturally sensitive services. Few substance use treatment programs had specialized services for LGBTQ people (Talley, 2013). Further, it is unclear whether treatment programs are culturally sensitive to the needs of sexual minorities with intersecting sources of oppression related to multiple marginalized identities. More research is needed on the barriers to treatment in this vulnerable and underserved population.

Table 3.

Linear model of sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and relationship status on drinking quantity.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted main effects | Adjusted main effects | Two -way interactions | Three-way interaction | |||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| F | df | p | ηp2 | F | df | p | ηp2 | F | df | p | ηp2 | F | df | p | ηp2 | |

| Main effects | ||||||||||||||||

| Sexual identity | 16.55 | 1 | <.00 | 0.48 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 1.20 | 1 | 0.274 | 0.01 | 4.38 | 1 | <.00 | 0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity | 13.44 | 2 | <.00 | 0.02 | 5.47 | 2 | <.00 | 0.02 | 7.56 | 2 | 0.001 | 0.03 | 7.46 | 2 | <.00 | 0.03 |

| Relationship status | 1.86 | 2 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 1.86 | 2 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 2.02 | 2 | 0.134 | 0.01 | 2.92 | 2 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| Two-way interactions | ||||||||||||||||

| Sexual identity x race/ethnicity | 2.69 | 2 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 2.33 | 2 | 0.10 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Sexual identity x relationship status | 1.95 | 2 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 1.51 | 2 | 0.20 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Race/ethnicity x relationship status | 4.36 | 4 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 3.16 | 4 | <.00 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Three-way interaction | ||||||||||||||||

| Sexual identity x race/ethnicity x relationship status | 2.04 | 4 | 0.10 | 0.02 | ||||||||||||

NOTE: Models 2-4 adjust for age, education, employment, children in the home, and sex/gender of partner

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)/National Institutes of Health (NIH) Ruth Kirschstein Postdoctoral Individual National Research Service Award (F32 AA025816; C.B. Veldhuis, Principal Investigator) and by Research Grant No. R01 AA13328 (T. L. Hughes, Principal Investigator) from the NIAAA/NIH. Dr. Drabble’s time was supported in part by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIH) Research Grant No. R03 MD011481 (K. Trocki and L. Drabble, MPI’s). Note: the content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or NIH. The authors would like to thank the reviewers and editor for their extremely helpful suggestions on earlier drafts and also wish to express gratitude to the women who participated

References

- Antonovsky H, & Sagy S (1986). The development of a sense of coherence and its impact on responses to stress situations. The Journal of Social Psychology, 126(2), 231–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda F, Matthews AK, Hughes TL, Muramatsu N, Wilsnack SC, Johnson TP, & Riley BB (2015). Coming out in color: Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between level of sexual identity disclosure and depression among lesbians. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(2), 247–257. 10.1037/a0037644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, & Walters K (2011). Measuring multiple minority stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 163–174. 10.1037/a0023244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrantes RJ, Eaton AA, Veldhuis CB, & Hughes TL (2017). The role of minority stressors in lesbian relationship commitment and persistence over time. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(2), 205–217. 10.1037/sgd0000221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle J, & DeFreece A (2014). The impact of community involvement, religion, and spirituality on happiness and health among a national sample of black lesbians. Women, Gender, and Families of Color, 2(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine, 110(C), 10–17. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC, Munthe-Kaas HM, & Ross MW (2016). Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(4), 541–558. 10.1080/00918369.2015.1083788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich JR, Lehavot K, Glass JE, & Williams EC (2017). Differences in alcohol use and alcohol-related health care among transgender and nontransgender adults: Findings from the 2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(6), 861–866. 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bois, Du SN, Legate N, & Kendall AD (2019). Examining partnership–health associations among lesbian women and gay men using population-level data. LGBT Health, 6(1), 23–33. 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, & McCabe SE (2010). Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 468–475. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, Steffen A, Veldhuis CB, & Wilsnack SC (2018). Depression and victimization in a community sample of bisexual and lesbian women: An intersectional approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(1), 131–141. 10.1007/s10508-018-1247-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2008). When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles, 59(5–6), 312–325. 10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Meyer IH, Overstreet NM, Haile R, & Hansen NB (2015). Exploring discrimination and mental health disparities faced by black sexual minority women using a minority stress framework. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 39(3), 287–304. 10.1177/0361684314560730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho G, Reinka MA, & Quinn DM (2019). Disclosure and Concealment of Stigmatized Identities. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1–23. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo A (2016). The impact of discrimination on mental health symptomatology in sexual minority immigrant Latinas. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(3), 283–292. 10.1037/sgd0000172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo A (2020). Expanding the reach of Latinx psychology: Honoring the lived experiences of sexual and gender diverse Latinxs. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 8(1), 1–6. 10.1037/lat0000144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo A, & Ramirez A (2020). Perceived discrimination, alcohol use disorder and alcohol-related problems in sexual minority women of color. Journal of Social Service Research, 0(0), 1–14. 10.1080/01488376.2019.1710657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clausell E, & Roisman GI (2009). Outness, Big Five personality traits, and same-sex relationship quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26(2-3), 211–226. 10.1177/0265407509106711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran BN, Peavy KM, & Robohm JS (2007). Do specialized services exist for LGBT individuals seeking treatment for substance misuse? a study of available treatment programs. Substance Use & Misuse, 42(1), 161–176. 10.1080/10826080601094207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, & Mays VM (2000). Relation between psychiatric syndromes and behaviorally defined sexual orientation in a sample of the US population. American Journal of Epidemiology, 151(5), 516–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit M, Kataji K, Drabble L, & Trocki K (2011). Sexual-minority women and alcohol: Intersections between drinking, relational contexts, stress, and coping. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 23(3), 351–375. 10.1080/10538720.2011.588930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RWS, Blosnich JR, Bukowski LA, Herrick AL, Siconolfi DE, & Stall RD (2015). Differences in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems between transgender- and nontransgender-identified young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154, 251–259. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DM, & Molix L (2015). Social stigma and sexual minorities’ romantic relationship functioning: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(10), 1363–1381. 10.1177/0146167215594592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble LA, Wootton AR, Veldhuis CB, Perry E, Riggle EDB, Trocki KF, & Hughes TL (2020). It’s complicated: The impact of marriage legalization among sexual minority women and gender diverse individuals in the U.S. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L, Midanik LT, & Trocki K (2005). Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual respondents: results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66(1), 111–120. 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, & London B (2018). Bipositive events: Associations with proximal stressors, bisexual identity, and mental health among bisexual cisgender women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(2), 204–219. 10.1037/sgd0000281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Feinstein BA, & London B (2014). Dimensions of sexual identity and minority stress among bisexual women: The role of partner gender. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 441–451. 10.1037/sgd0000063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Feinstein BA, Stephens J, Zimmerman AR, Newcomb ME, & Whitton SW (2019). Nonmonosexual stress and dimensions of health: Within-group variation by sexual, gender, and racial/ethnic identities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1–15. 10.1037/sgd0000348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, Lytle A, London B, & Levy SR (2017). An experimental investigation of the application of binegative stereotypes. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(3), 314–327. 10.1037/sgd0000234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Eaton AA, Rose SM, Riger S, & McHugh MC (2012). Feminism and psychology: Analysis of a half-century of research on women and gender. American Psychologist, 67(3), 211–230. 10.1037/a0027260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, & Hyde JS (2016a). Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: I. Theoretical and epistemological issues. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(2), 155–170. 10.1177/0361684316629797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, & Hyde JS (2016b). Intersectionality in quantitative psychological research: II. Methods and techniques. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 1–18. 10.1177/0361684316647953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Everett BG, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hughes TL (2016a). The impact of civil union legislation on minority stress, depression, and hazardous drinking in a diverse sample of sexual-minority women: A quasi-natural experiment. Social Science & Medicine, 1–11. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett BG, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hughes TL (2016b). The impact of civil union legislation on minority stress, depression, and hazardous drinking in a diverse sample of sexual-minority women: A quasi-natural experiment. Social Science & Medicine, 169, 180–190. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Latack JA, Bhatia V, Davila J, & Eaton NR (2016). Romantic relationship involvement as a minority stress buffer in gay/lesbian versus bisexual individuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 1–21. 10.1080/19359705.2016.1147401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson AD, Carr G, & Snitman A (2014). Intersections of race-ethnicity, gender, and sexual minority communities. In Miville ML & Ferguson AD (Eds.), Handbook of Race-Ethnicity and Gender in Psychology (pp. 45–63). New York, NY: Springer New York. 10.1007/978-1-4614-8860-6_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, & Wiersma JD (2012). Romantic relationships and alcohol use. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 5(2), 98–116. 10.2174/1874473711205020098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE, Anderson RE, Tarasoff LA, & Robinson M (2019). Bisexual stigma, sexual violence, and sexual health among bisexual and other plurisexual women: A cross-sectional survey study. The Journal of Sex Research, 88, 1–13. 10.1080/00224499.2018.1563042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders CE, Shuler SA, Desnoyers SA, & VanKim NA (2020). Relationships between social support, identity, anxiety, and depression among young bisexual people of color. Journal of Bisexuality, 19(2), 253–275. 10.1080/15299716.2019.1617543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Follins LD, Walker JJ, & Lewis MK (2014). Resilience in black lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A critical review of the literature. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 18(2), 190–212. 10.1080/19359705.2013.828343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]