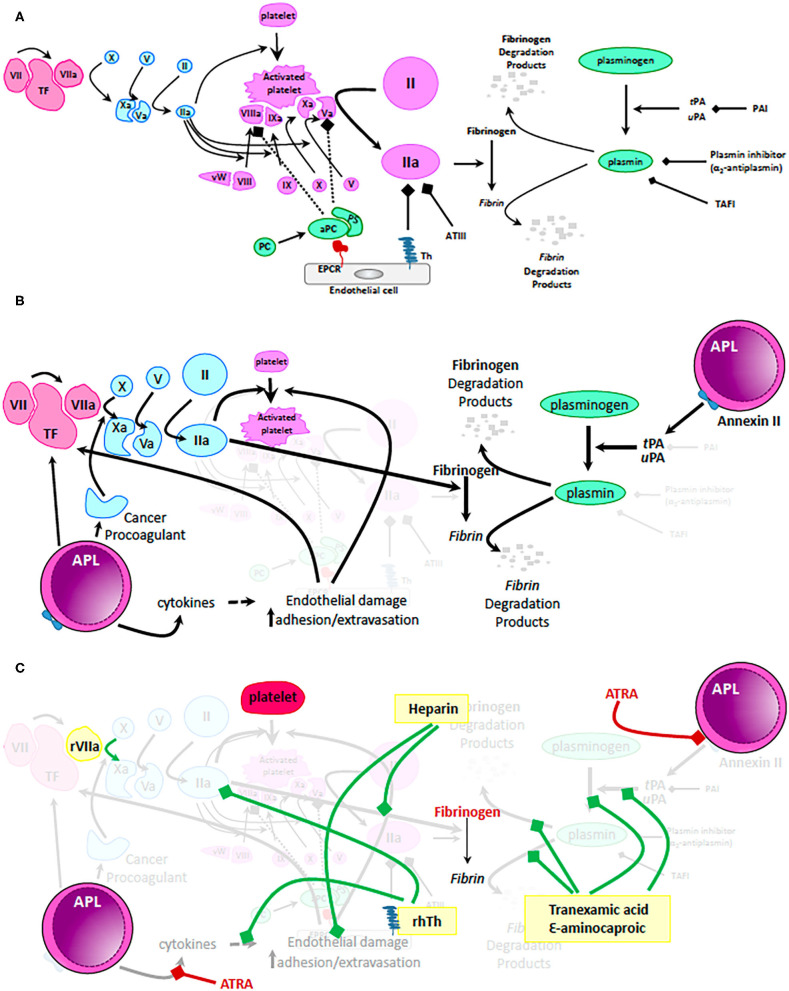

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of coagulopathy in APL. (A) Physiologic mechanisms of coagulation and anticoagulation. Tissue factor (TF) released by trauma to the vascular wall activates factor VII. Small amounts of activated factor VII (VIIa) activates factor X which in turn activates factor V. Activated factor X (Xa) together with activated factor V (Va) cleaves and activates prothrombin to thrombin (IIa). Only small amounts of thrombin are generally produced via this mechanism. These levels are insufficient to form a robust fibrin clot but can activate platelets, factor VIII, factor X, and factor V resulting in generation of clinically significant amounts of IIa on the surface of activated platelets. High levels of IIa are now sufficient to cleave fibrinogen to fibrin and thus, stabilize the clot. During normal hemostasis, clot formation is restricted to the place of endothelial damage via: (i) mechanisms dependent on endothelial cell expression of thrombomodulin (Th - binds and inactivates IIa) and endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR – binds and activates protein C, which together with protein S inactivates IIa, Va, and VIIIa); (ii) antithrombin III (ATIII – binds and inactivates IIa) and (iii) fibrinolysis pathway that results in generation of plasmin from plasminogen. tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; uPA, urine plasminogen activator; PAI, plasminogen activator inhibitor; TAFI, thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor. (B) Mechanisms by which the coagulation pathways are dysregulated in patients with APL. Malignant promyelocytes produce excessive amounts of TF, cytokines (i.e., IL1β, TNFα) and cancer procoagulant leading to unrestricted generation of massive amounts of IIa and consumptive coagulopathy. In addition, APL promyeloblasts express high levels of Annexin II, a receptor and activator of tPA/uPA resulting in uncontrolled generation of plasmin and hyperfibrinolysis. (C) Mechanistic impact of therapeutic interventions routinely used in APL. Standard of care recommendations are depicted with red highlighting, text and bars (platelets, fibrinogen, or fresh frozen plasma and ATRA). Of note, ATRA can rapidly (within minutes) decrease expression of Annexin II and thus, ameliorate hyperfibrinolysis. In yellow boxes are proposed interventions that are not currently recommended as routine but that may positively influence the coagulopathy of some patients with APL. Green bars depict suggested mechanisms of action of these proposed interventions. Recombinant VIIa has been used in patients with life threatening intracranial bleeding; low dose heparin not only decreases consumption of coagulation factors by blocking IIa but also alleviates endothelial damage; fibrinolysis inhibitors (tranexamic acid and ε-aminocaproic acid) can mitigate hyperfibrinolysis and excessive fibrinogen consumption. Most exciting is the potential use of recombinant human thrombomodulin (rhTh) to not only balance IIa activity but also palliate some of the cytokine dependent endothelial damage. While these interventions may have a role to play in management of coagulopathy in APL, further clinical trial data are needed before making firm recommendations.