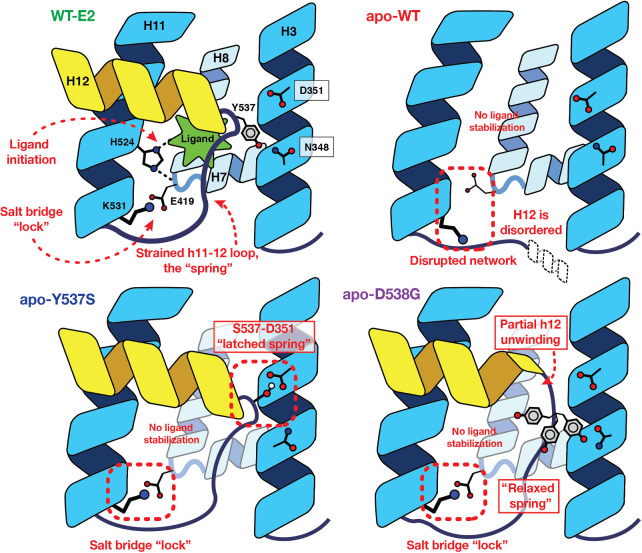

Figure 6.

The “Spring-Loading” Model consolidating the effects of ligand binding and the activating mutations in ER. In WT receptor, a ligand-mediated hydrogen-bonding network forms, crisscrossing H7, H8, and H11, and terminating with a salt bridge formed across the base of the ligand-binding pocket. In the absence of ligand, His524 is no longer ordered, and the remainder of the network fails to form. Introduction of either the Y537S or D538G mutations, however, overcomes the strain energy of the H11–12 loop to allow the terminal salt bridge to form in the absence of ligand. Specifically, the Y537S mutation yields an optimal hydrogen bond between H3 and H12, operating as a “latch” holding H12 in the activated conformation. The D538G mutation, by contrast, induces a partial unwinding of H12, which serves to relax the backbone strain energy of the spring-like loop.