Abstract

Background

Substance use disorder (SUD) is a leading contributor to the global burden of disease. In Indonesia, the availability of formal treatment for SUD falls short of the targeted coverage. A standardised therapeutic option for SUD with potential for widespread implementation is required, yet evidence-based data in the country are scarce. In this study, we developed a cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)-based group telemedicine model and will investigate effectiveness and implementability in a multicentre randomised controlled trial.

Methods

A total of 220 participants will be recruited from the social networks of eight sites in Indonesia: three hospitals, two primary healthcare centres and three rehabilitation centres. The intervention arm will participate in a relapse prevention programme called the Indonesia Drug Addiction Relapse Prevention Programme (Indo-DARPP), a newly developed 12-week module based on CBT and motivational interviewing constructed in the Indonesian context. The programme will be delivered by a healthcare provider and a peer counsellor in a group therapy setting via video-conferencing, as a supplement to participants’ usual treatments. The control arm will continue treatment as usual. The primary outcome will be the percentage increase in days of abstinence from the primarily used substance in the past 28 days. Secondary outcomes will include addiction severity, quality of life, motivation to change, psychiatric symptoms, cognitive function, coping, and internalised stigma. Assessments will be performed at baseline (week 0), post-treatment (week 13), and 3 and 12 months post-treatment completion (weeks 24 and 60). Retention, participant satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness will be assessed as the implementation outcomes.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of Universitas Indonesia and Kyoto University. The results will be disseminated via academic journals and international conferences. Depending on trial outcomes, the treatment programme will be advocated for adoption as a formal healthcare-based approach for SUD.

Trial registration number

UMIN000042186.

Keywords: substance misuse, telemedicine, psychiatry, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The proposed study will be the first to establish high-quality evidence for a cognitive behavioural therapy-based relapse prevention programme for substance use disorder (SUD) in Indonesia.

Telemedicine enables far-reaching, nationwide participation, connecting participants from across the nation with providers in major cities.

A successful outcome may produce a new SUD treatment module in Indonesia and pave the way for its adoption by national guidelines.

Study limitations include risk of recall and social desirability bias, heterogeneous control conditions, and possible variability in treatment provision.

Introduction

Substance use disorder (SUD) is characterised by the inability to control the use of psychoactive substances, such as alcohol and psychotropic drugs, which disrupt daily living. SUD remains a significant and growing health problem worldwide. According to the 2016 Global Burden of Disease survey, SUD contributed to 131 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) or 5.5% of all DALYs,1 and its prevalence has been increasing since the 1990s.2 While substance use itself is more widespread in high-income countries, low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) had disproportionately high SUD mortality rates. The absolute mortality rate due to SUD was greatest in LMICs with large populations,3 and people with economic disadvantages were more likely to develop SUD.4 The Movement for Global Mental Health and the WHO have found substantial treatment gaps in LMICs. For instance, the number of individuals with SUD far exceeds the availability of formal treatment services.5–7 While these numbers do not take traditional care into account, it is still concerning that only 1% of individuals with SUD in LMICs have reported receiving government-standardised treatment.8

In Indonesia, the world’s third most populous LMIC, government statistics have estimated the prevalence of drug use to be 1.8% or 3.3 million residents, with the most used substance being marijuana (68%), followed by amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS, 42%), opioids (38%), and sedatives (35%).9 10 While injecting drug use decreased by 80% between 2002 and 2016,10 unprescribed use of psychoactive medications like benzodiazepines has become significant.11 Similar to other Muslim majority countries,12 alcohol consumption is comparatively low in Indonesia, with alcohol use disorder being prevalent only among 0.8% residents in 2016, much lower than the overall rate in Southeast Asia (3.9%).13 However, new psychoactive substances (NPS) have entered the country in the last decade.14 Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic may further complicate the SUD situation in Indonesia, as has been observed in other countries.15 For instance, unpublished data from our coauthor (KS) revealed that since the pandemic began in early April 2020, both drug and alcohol use have increased in Indonesia by up to 2.5%. Increased drug use might have been influenced by lockdown isolation, socioeconomic issues due to unemployment, and severe psychological burden.

In Indonesia, formal mental health providers and facilities are severely lacking. In a nation of 267 million people, only 773 psychiatrists (0.32/100 000 people) are employed—the second lowest proportion in Southeast Asia16—across hospitals with psychiatric care, half of which are located in the capital island of Java.17 Among the ~1700 government-run primary healthcare centres (abbreviated as Puskesmas in Indonesian), only a fifth actively provide mental healthcare.17 18 Current formal treatment options for SUD include one-on-one supportive psychotherapy, symptomatic pharmacotherapy, peer counselling, and opioid substitution. Methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) has been available in Puskesmas since 2006, but as of 2012, its coverage was only 5%,19 due to methadone cost, reliance on subsidisation, lack of programme sustainability,20 and the tendency to incarcerate patients under the ‘war on drugs’ policy.19 21 The 3-month retention rate of MMT was only 60%–74%.22 23 Psychiatric comorbidities and lower quality of life are common among MMT recipients.24 Most concerningly, insufficient formal treatment coverage and the lack of standardised care for SUD have prompted policymakers to enact punitive criminalisation practices, which are even more stringent under the current administration, instead of a comprehensive mental healthcare approach.25 26

Behavioural therapies in many forms are commonly administered for SUD, the most popular method being cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). There is strong evidence supporting the efficacy of CBT in treating SUD. A meta-analysis reported a moderate overall effect size (d=0.45) of CBT treatments, with outcomes such as self-reported abstinence, drug-free urine at treatment exit, and increased retention in therapy.27 28 CBT strategies include: (a) contingency management (CM),29 which introduces rewards for abstinence, (b) motivational interviewing (MI), which explores and resolves ambivalence,30 31 (c) relapse prevention (RP), which helps participants to identify high-risk triggers and prevent cravings, or (d) combinations thereof.32 Therapy can be delivered individually or in groups; the latter has reportedly increased adherence and self-disclosure, and decreased the treatment duration by 40%.33 34 CBT (particularly MI and RP) is relatively low-cost and can be delivered by non-specialists, making it adaptable to and beneficial in settings with limited formal mental health professionals.35 36 In LMICs, while ample randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have supported the efficacy of CBT in reducing alcohol use,37 38 evidence for treating drug use disorders is limited, with only five RCTs published so far.39–43 Among these, three were inpatient-based, even though SUD management mandates sustainable outpatient care in community settings.

Telemedicine has the potential to improve SUD treatment coverage in Indonesia. Internet communication overcomes the geographical barriers of the Indonesian archipelago and saves time as well as transportation costs for both patients and providers, both in remote areas where health services are sparse,44 and in major cities with heavy traffic, such as Jakarta.45 Privacy is also better ensured online as opposed to in visiting clinics, where there is a greater risk of inappropriate disclosure of SUD diagnoses, which is one of the most stigmatised health conditions.46 Synchronous telemedicine via live video feed connects participants in real-time, improving rapport and potentially adherence, as compared with asynchronous telemedicine (eg, through text messages or web application). Video-conferencing has been effectively used in SUD treatment;47–52 however, recent systematic reviews53–58 have revealed three gaps in research: (1) previous reports have only focused on alcohol and opioid use,47 50–52 (2) group therapy was investigated by only one small-scale pilot RCT,51 and (3) no studies have been conducted in LMICs. This latter gap is particularly relevant because the use of internet devices has been rapidly expanding in LMICs, including Indonesia. Smartphone users accounted for 74% of the Indonesian population in 2019, possibly reaching 89% by 2025.59 The COVID-19 pandemic has further elevated telemedicine from an accessory to a necessity, including for psychiatric care.60 Its accessibility and acceptance among patients with SUD, as shown in a recent survey,61 may potentially sustain telemedicine as the ‘new normal’ even in the post-pandemic world.62 63

Given the above challenges and opportunities, we propose a clinical trial to evaluate a RP telemedicine programme for SUD in Indonesia. We have developed a new 12-week CBT-based group therapy called the Indonesia Drug Addiction Relapse Prevention Programme (Indo-DARPP), which will be delivered via video conference (tele-Indo-DARPP). The primary objective will be to evaluate the effectiveness of tele-Indo-DARPP in addition to treatment as usual (TAU) towards increasing abstinence from primarily used substances, as compared with the effectiveness of TAU only. The secondary objectives will be to assess impacts on quality of life, motivation to change, psychological symptoms, cognitive function, coping, and internalised stigma. Retention, participant satisfaction, and group cohesion will be assessed as implementation outcomes, and cost-effectiveness analyses will be conducted to inform health policy investments.

Methods

Trial design

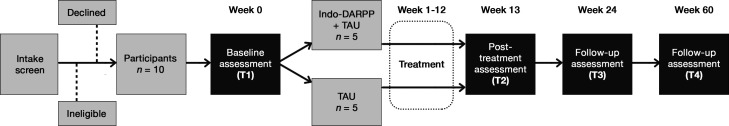

This trial is a parallel-group, two-arm, assessor-blinded, multicentre RCT. The protocol adheres to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) checklist (online supplemental file 1). We designed the study as a pragmatic type 1 hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial,64 which allows concurrent investigation of intervention effectiveness as well as implementation in clinical practice, focusing on the former. After intake screening, participants will undergo baseline assessment (T1) and be randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio, either to the intervention arm receiving tele-Indo-DARPP in addition to TAU, or the control arm receiving TAU only. Treatment will be administered for 12 weeks, followed by a post-treatment assessment (T2) at week 13, and follow-up assessments (T3) at week 24 and (T4) at week 60 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart for each site. A total of 20 or 30 participants will be recruited through the social network of each site. After 10 participants have been recruited to constitute one wave, they will be randomly allocated into two arms: intervention (Indo-DARPP+TAU) and control (TAU only), with five participants in each arm. Recruitment will be continued until another 10 or 20 participants (second or third wave) join, in a similar procedure. Treatment period will be 12 weeks. Assessments will be conducted four times: T1 (week 0) during baseline or before randomisation, T2 (weeks 13–16) during postassessment or 1–4 weeks after treatment period ends, T3 (week 24) at 3 months after treatment ends and T4 (week 60) at 12 months after treatment ends. DARPP, Drug Addiction Relapse Prevention Programme; TAU, treatment as usual.

bmjopen-2021-050259supp001.pdf (84.6KB, pdf)

Participants and settings

Participants will be recruited across Indonesia via social networks of eight sites: two primary health centres (Puskesmas), three referral hospitals, and three drug rehabilitation services (table 1). These facility types constitute the community-based treatment model for SUD in Indonesia,65 encompassing patients with diverse motivations for behavioural change, substance use histories, comorbidities, and stages of treatment. Recruitment will be conducted via online advertisements (ie, on social networking services, group chat, website) and through consecutive sampling by directly approaching current and former clients through outpatient services. Although all targeted facilities are located in urban settings, the recruitment process will include social media services of each site, particularly rehabilitation centres, which have nationwide coverage. Hence, we expect that participants will be recruited from anywhere in Indonesia and will not be limited to the physical scope of each site.

Table 1.

Recruitment sites in this study

| Name | Location | Type | Treatment as usual | Most reported primarily used substance |

| Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital | Jakarta | Tertiary national general hospital | Individual psychotherapy, symptomatic pharmacotherapy | Benzodiazepine |

| Aceh Mental Hospital | Aceh | Tertiary provincial mental hospital | Individual psychotherapy, symptomatic pharmacotherapy | Methamphetamine |

| Duren Sawit Regional Hospital | Jakarta | Tertiary regional general hospital | Individual psychotherapy, symptomatic pharmacotherapy, opioid substitution therapy (buprenorphine, naloxone) | Opioid |

| Karisma Foundation | Jakarta | Rehabilitation centre | Individual and group peer counselling | Methamphetamine, opioid |

| Kapeta Foundation | Banten | Rehabilitation centre | Individual and group peer counselling | Methamphetamine, benzodiazepine, synthetic cannabinoids |

| Kios Atma Jaya | Jakarta | Rehabilitation centre and regional HIV clinic | Individual psychotherapy, group peer counselling, outreach programme | Opioid |

| Puskesmas Jatinegara | Jakarta | Primary healthcare | Counselling, symptomatic pharmacotherapy, methadone maintenance therapy | Heroin |

| Puskesmas Gambir | Jakarta | Primary healthcare | Counselling, symptomatic pharmacotherapy, methadone maintenance therapy | Heroin |

Counselling focuses on education and giving advice.

Symptomatic pharmacotherapy gives medication for helping patients with specific psychopathologies.

Psychotherapy aims to help a person identify and change their emotions, thoughts, and behaviour.

The services offered by each type of site vary. Puskesmas provide general primary care, pharmacotherapy for cases without complications and MMT. Referral hospitals provide psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, opioid substitution therapy using buprenorphine/naloxone, and specialised care for cases with complications, such as severe psychiatric disorders. Rehabilitation services provide long-term psychosocial care, typically in a mutual-aid group. Sites were selected based on feasibility, client demographics, recruitment potential, and availability of providers. While recruited participants may not be undergoing treatment at these sites at the time, facilitators for tele-Indo-DARPP will be staff members of the respective sites: general practitioners in Puskesmas, psychiatrists in referral hospitals, and counsellors in rehabilitation centres.

Inclusion criteria will be those who: (1) be aged 18–65 years old; (2) be diagnosed with SUD based on DSM-5; (3) have used primarily used substances for at least 1 day in the past year; (4) have access to electronic devices (ie, smartphone, mobile tablet, personal computer) with internet connection and (5) be proficient in Indonesian. Individuals who (1) have severe comorbidities that hinder informed consent or group therapy participation and (2) are hospitalised or using residential care, will be excluded.

We set a broad inclusion criterion, that is, substance use in the past 1 year, for two reasons. First, proportional hazard models have showed that the probability of relapse remains high before achieving 1 year of abstinence, and declines substantially only after 16 months.66 67 Thus, it is clinically important to examine treatment efficacy for people who have not achieved 1-year abstinence.67 Second, in this pragmatic effectiveness study,68 we designed eligibility criteria to accurately represent the population encountered in real-world Indonesian clinical practice. Indeed, patients treated at the collaborating clinical sites include those who have been abstinent for more than 1 month but still experience cravings and a tendency to relapse.

Recruitment

Patient eligibility will be assessed by collaborating staff at the respective sites. Addiction psychiatrists will conduct clinical assessments via video calls for those who have never been diagnosed with SUD. The consent form in English is provided in online supplemental file 2. For urine tests, explanations will be given immediately after post-treatment (T2) assessment, as anticipation for urine tests may influence substance use behaviour. Consent to urine tests or absence thereof will not affect study participation.

bmjopen-2021-050259supp002.pdf (115.9KB, pdf)

Randomisation and blinding

Depending on the study site, participants will be randomly allocated to either the intervention (tele-Indo-DARPP+TAU) or the control (TAU only) arm. Each site will conduct two or three waves of recruitment, with 10 participants in each wave. For each wave at a site, we will randomly allocate five participants to either the intervention or control arm. All participants in each tele-Indo-DARPP group will belong to the same recruitment site. Allocation will be performed using computer-generated random numbers by a researcher who will be blinded to the participants' information, except for ID. Data will be collected by researchers who are blinded to participants’ study conditions. Participants and treatment providers will not be blinded, as it would not be possible given the psychotherapeutic nature of the intervention.

Development of the Indo-DARPP

The Indo-DARPP is based on the Serigaya Methamphetamine Relapse Prevention Programme (SMARPP), a face-to-face CBT-based group intervention developed by a coauthor (TM) in Japan,69 which itself is based on the Matrix Model developed in the USA.70 It has demonstrated efficacy in increasing abstinence duration, motivation to change, and participation in self-help groups.71–73 SMARPP is covered by the national insurance scheme and has been widely implemented as a psychotherapy for SUD in psychiatric clinics and in primary healthcare centres, rehabilitation centres, and probation offices in Japan. SMARPP has excellent scalability as it is delivered through workbooks and can be facilitated by non-specialists who have received brief training.

The contents of Indo-DARPP are based on the RP model, where participants are guided to learn about high-risk situations for substance use, and coping strategies. Elements of MI are incorporated in the earlier parts of the workbook in a form of open questions to assess participants’ ambivalence and motivation to change. The programme also includes psychoeducation on substances, SUD and common comorbidities. While CM could also be added, it increases cost and may not be effective in the longer term;74 thus, only MI and RP approaches will be used in this study. Adaptations from SMARPP were determined via focus group discussions involving Japanese researchers and psychiatrists, general practitioners, and peer counsellors based in Indonesia, all of whom have extensive experience ranging from 4 to 20 years in the addiction field. The substances discussed in the module are ATS, benzodiazepines and other prescribed medicines, opioids, marijuana, NPS, and alcohol. Indo-DARPP is designed to be delivered in a small group format using a workbook (see online supplemental file 3 for the table of contents of the workbook). Sessions will be delivered by one facilitator and one peer counsellor with lived experiences of SUD as cofacilitator.

bmjopen-2021-050259supp003.pdf (82.4KB, pdf)

A pilot test was conducted at Site 1, with nine patients with SUD recruited for a 12-week tele-Indo-DARPP to check content acceptability and feasibility of the online delivery format. Further adjustments were made based on pilot results and patient feedback.

Intervention via video conference: tele-Indo-DARPP

Tele-Indo-DARPP will be delivered as group therapy for 12 weeks in weekly 2-hour sessions over the online video-conferencing application Zoom, with a maximum of five participants. The research team will provide video conference links to participants and two providers. Participants who agree to share their contact information will receive the links on an online group chat, while others will be notified via personal messages. Each Indo-DARPP session consists of three parts: (1) ‘check-in’, where participants share history of substance use and craving in the past week, and analyse high-risk situations and coping actions taken; (2) ‘today’s topic’, where providers guide discussions of specific workbook chapters and participants complete exercises, and (3) ‘check-out’, where providers give summary and invite feedback, and participants anticipate triggers and coping strategies for the following week.

Providers of tele-Indo-DARPP

At least two persons from each site will serve as facilitators, who meet either of the following criteria: psychiatrists with at least a year of experience in treating patients with SUD, healthcare providers with at least 2 years of experience in providing care for patients with SUD, or peer counsellors with at least 2 years of involvement with any organisations providing services for patients with SUD. The roles of facilitators are to: (1) lead and moderate Indo-DARPP sessions, (2) elaborate on chapter contents, (3) manage participants to follow rules, (4) establish a safe and warm environment, (5) provide consultation, including out-of-session, and (6) contact absent participants to encourage attendance.

Similarly, at least two persons from each site will serve as cofacilitators for the tele-Indo-DARPP. Cofacilitators will be peer counsellors who have also experienced SUD and recovered, with at least 6 months of involvement with any organisations providing services for patients with SUD. The role of cofacilitators is to: (1) share personal experiences relevant to discussion topics, (2) assist facilitators in ensuring a safe and warm environment, (3) provide general support to the Indo-DARPP process, and (4) provide counsel, both in and out of sessions.

Training and supervision

Prior to recruitment, all providers will receive two full-day online training sessions on basic knowledge of SUD treatment, Indo-DARPP content, principles of MI (eg, empathy, reflective listening, empowering affirmations), video demonstrations, hands-on role play, discussion of difficult cases, and study-related quality control. Workbooks and manuals will be handed to all providers, and close communication with the research team will be maintained via a WhatsApp group chat throughout the research period. To maintain treatment fidelity and quality control, during actual tele-Indo-DARPP sessions, addiction psychiatrists from the research team (KS and EH) will randomly select and observe at least two sessions per Indo-DARPP group. Observations will be conducted at each wave at each site, constituting 16.7% of all sessions, and will be reviewed using a structured checklist.

Control condition

Participants who received treatment before the study will continue to receive TAU, regardless of group allocation. TAU was chosen as the control condition because it is expected to complement the existing treatment services for SUD at every level of care. The TAU differs according to service location (table 1). Individual psychotherapy is typically conducted via in-person short consultations (~15 min) with clinical psychiatrists. Pharmacotherapy is used to alleviate symptoms, by prescribing medications such as anxiolytics for conditions such as anxiety. Patients undergoing MMT visit their sites almost every day to receive their daily doses, while patients undergoing substitution therapy with buprenorphine with naloxone visit every week. All participants will be able to continue any outpatient pharmacological treatment (eg, MMT, antidepressants) and psychotherapy (eg, 12-step group sessions).

Primary outcome

Abstinence from primarily used substance

The primary outcome is the percentage of days of abstinence from the primarily used substance in the past 28 days. Per cent days of abstinence have been shown to be sensitive to the effects of CBT and are good predictors of SUD treatment follow-up.75 Data on the use of primarily used substances each day (measured in a yes/no format) for 28 days will be retrospectively collected on a weekly basis using the timeline follow-up (TLFB) method (table 2), which has good validity and high test-retest reliability in measuring substance consumption.76 77 The participants will be asked to recount every week to reduce the risk of recall bias. The primarily used substance refers to the most problematic substance for participants, which has driven them to seek care at T1.

Table 2.

Outcome and measurement

| Outcome | Measurement | Data for analysis | Type and score range | Hypothesis for intervention (vs control) | Assessment time point | |||

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |||||

| Primary outcome | ||||||||

| Abstinence from primary substance | TLFB for the past 28 days | Number of days being abstinent from primary substance divided by 28 (%). | Continuous, 0 (no use) to 100 (used every day). |

Higher | ✔︎ | ✔︎* | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| Addiction severity | ASI | 7 composite scores: medical, employment, alcohol use, drug use, legal, family/social and psychiatric status. Each composite score calculated using standard formula. | Continuous, 0 (no problems) to 1 (severe problems). | Lower | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Health-related quality of life | EQ-5D-5L | Health utility score, calculated from 5 items on mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, using Indonesian value set. | Continuous, −0.865 (impaired health) to 1 (full health). | Higher | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Motivation to change | URICA | Action stage subscale, sum of 8 items. | Continuous, 8 (not active in behavioural change) to 40 (highly active in behavioural change). | Higher | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Coping | Brief COPE | Sum of substance use coping (2 items) | Continuous, 2 (low substance use coping) to 8 (high substance use coping). | Lower | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Psychiatric symptoms | SCL-90-R | GSI, average of 90 items. | Continuous, 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (severe symptoms). | Lower | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Cognitive function | RAVLT | 3 test results; immediate, learning and recalling. | Continuous, 0 (low functioning) to 15 (high functioning). | Higher | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Internalised stigma | ISMI | Sum of 4 subscales: alienation, stereotype endorsement, social withdrawal and stigma resistances. | Continuous, 24 (low internalised stigma) to 96 (high internalised stigma). | Lower | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ |

| Implementation outcomes | ||||||||

| Retention in treatment | Self-reporting for the past 3 months | Coded as ‘retained’ if they had therapeutic contacts in at least 75% of the planned number of therapeutic contacts. | Categorical, 'retained'=1, 'not retained'=0. | More 'retained' | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | ✔︎ | |

| Treatment satisfaction | CSQ-3 | Sum of 3 items. | Continuous, 4 (not satisfied) to 12 (satisfied). | Higher | ✔︎ | |||

| Group cohesion | GTES | Sum of 16 items. | Continuous, 16 (poor cohesion) to 80 (great cohesion). | Not applicable: measured only in intervention arm | ✔︎ | |||

*Objective validation by urine drug test for eight substances: alcohol, amphetamine, morphine, cannabinoids, methamphetamine, benzodiazepine, cocaine, synthetic cannabinoids.

ASI, Addiction Severity Index; COPE, Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced; CSQ-3, Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-3; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5D; GSI, Global Severity Index; GTES, Group Therapy Experience Scale; ISMI, Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90 Revised; TLFB, timeline follow-up; URICA, University of Rhode Island Change Assessment.

Urine samples will be collected to test for the presence of the primarily used substance once at T2. Thresholds for a positive result are >100 ng/mL for ethyl glucuronide (alcohol), >300 ng/mL for ATS (ie, d-methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), >100 ng/mL for diacetylmorphine (heroin), cocaine and benzodiazepine, >50 ng/mL for synthetic cannabis (K2), and >25 ng/mL for tetrahydrocannabinol (marijuana). Urine tests in this study will only serve to corroborate the data of self-reported substance use at the primary endpoint (T2), not as an objective substitute of all self-reported substance use data at every time point. This was planned to improve feasibility for participants and minimise dropout due to the burden of data collection (urine test needs in-person assessment, unlike all other measurements in this study), especially among participants who reside in remote areas who are deemed to benefit the most from online therapy.

Secondary outcomes

Addiction severity

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) is the most widely used measure in the field of addiction.78 Internal consistency, test-retest reliability and scale independence of ASI to measure substance use have long been established.79 80 The Treatnet ASI V.3.0 by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime will be used; the scale is available in Indonesian, and one addiction treatment centre in Indonesia was included in its development trial.81

Health-related quality of life

The five-level version of the five-dimensional EuroQoL (EQ-5D)82 83 will be used to assess health-related quality of life, which has been used before for patients with SUD with confirmed construct validity.84 85 The total utility score will be obtained using the already established value set in Indonesia.86

Motivation to change

Motivation to change will be assessed by the Action subscale of the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA)87 which has been shown to have good validity. Higher scores indicate that the person has committed to develop positive behavioural changes.88

Coping

Types of engaged stress coping will be assessed by the Brief Coping Orientations to Problems Experienced,89 which is commonly used for patients with SUD.90 Higher scores for specific types indicate that patients have adopted them more frequently.

Psychiatric symptoms

Psychiatric symptoms will be evaluated by the Symptom Checklist 90 R.91 The Global Severity Index will be used, which is widely used for measuring psychiatric symptoms among patients with SUD.92

Cognitive function

Cognitive function will be assessed by the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test,93 which is useful for diagnosing cognitive impairment as well as post-treatment improvement in patients with SUD.94 95

Internalised stigma

Internalised stigma will be assessed using the Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness scale.96 The term ‘mental illness’ in the statements will be replaced with ‘substance addiction’.

Implementation outcomes

Retention in treatment

Participants will be coded as ‘retained in treatment’ if they have had therapeutic contact, including attending tele-Indo-DARPP and visiting any outpatient clinic for TAU, in at least 75% of planned contacts in the previous 3 months.

Treatment satisfaction

The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-397 will be used, as it is commonly used for treatment programmes, including for SUD.98

Group cohesion

The Group Therapy Experience Scale will be used to measure the level of group cohesion and self-disclosure in group therapy, as implementation outcomes of tele-Indo-DARPP.99

Indo-DARPP attendance

Attendance of each session will be recorded by the facilitator.

Cost effectiveness

Cost-effectiveness will be assessed from patient, provider, and societal perspectives. Cost data will be calculated by multiplying the quantity of used resources by the unit price. Data on quantity and unit price will be obtained from within the trial or estimated from relevant data sources. For effectiveness data, both clinical and economic indices will be used. The clinical index will be based on days of abstinence from the primarily used substance in the previous 28 days, which will be converted into years of abstinence. The economic index will be based on the quality-adjusted life year (QALY) calculated from the utility score of the EQ-5D.

Feedback interviews

Semistructured interviews will be conducted with both participants and providers to assess the following: satisfaction with content quality, comprehensibility, technical experience regarding video-conferencing, comfort, module practicability, language barriers and participants’ perception of the credibility of providers. Interviews will be audio-recorded with the interviewees’ consent.

Participant characteristics

The following data will be obtained via a self-administered questionnaire: age, gender, approximate residential location, marital status, household cohabitants, ethnicity, religion, highest education level, employment status, individual and household income, type of internet device used, frequency of video calls in the past year, age during first instance of drug use, primarily used substance, inpatient history or incarceration in the past month, types of treatments received, treatment locations in the past 3 months, status of current outpatient care (voluntary or involuntary, legal or non-legal) and transportation time and cost from residence to outpatient locations.

Data collection procedure

Researchers blinded to the treatment allocation will collect data at four different time points: at baseline (week 0, T1), the week after the completion of treatment (week 13, T2), 3 months after the completion of treatment (week 24, T3), and 12 months after the completion of treatment (week 60, T4), using self-answered questionnaires and online one-on-one interviews. For the primary outcome, participants will be asked to recall weekly drug use using the TLFB, with a period of approximately 4 weeks between each assessment. Urine specimens will be collected only at T2 and at the final 2 weeks within the TLFB assessment period. The assessment schedule is presented in table 2 and figure 2. To facilitate honest disclosure from participants, we will not record any Indo-DARPP video-conferencing sessions throughout the study.

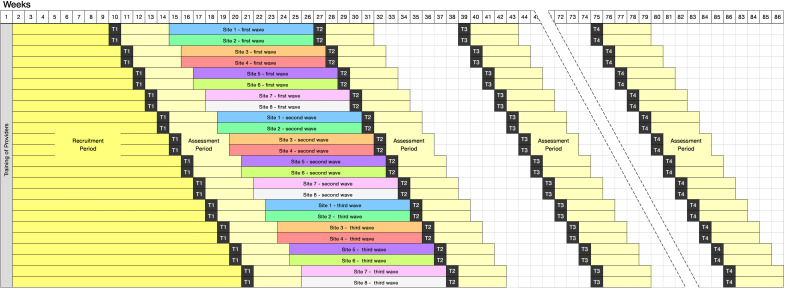

Figure 2.

Planned trial schedule across all eight research sites. Staggered schedules were designed to spread the assessment workload of providers and research staff. After training the providers, all sites will be given approximately 1–2 months to recruit participants. Sites with relatively higher potential to recruit faster, that is, those with higher rates of patient turnover, have been selected first in the schedule. Each site will have two or three waves of recruitment and treatment periods.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated for the primary outcome to detect a medium effect size of d=0.50, which is slightly more modest than that of a previous study examining the efficacy of telemedicine for people with SUD in an LMIC (d=0.59).100 Using α=0.05, power=0.80, a simple t-test requires n=64 per arm. We estimated the design effect of clustering within the Indo-DARPP group using the formula D=1+(m −1)ρ, 101 assuming intraclass correlation within Indo-DARPP groups or ρ=0.05, and group size or m=5, which yielded a design effect of D=1.2. We then multiplied n=64 by D=1.2, which yielded the minimal number of participants in the data analysis: n=77 per arm. Assuming an attrition proportion of 30% which is more conservative than a previous similar study (26%),102 the sample size for enrolment was set as 110 per arm, or 220 in total.

Statistical analysis

A detailed statistical analysis plan will be developed by a statistician who is blinded to the patient allocation prior to data analysis. Baseline data description and main analyses will be conducted on an intention-to-treat basis; that is, participants’ data will be handled according to their initially assigned arms, regardless of the actual received treatment. Analyses will be conducted with a significance level of 5% in the two-sided test, using Stata/SE V.16.1.

Consideration for correlated outcome data

The correlation within sites for the control arm will be ignored, as the TAU within one site varies per patient and some participants may not receive any treatment. For the intervention arm, the correlation within each Indo-DARPP group due to the nature of group therapy needs to be considered. We define a new variable termed ‘clustering group identification’ (CID), in which the control arm will be coded as a unique CID for each person, while the intervention arm will be coded based on the tele-Indo-DARPP group, hence assigning the same CID for all five participants.

Main analysis

The primary endpoint has been set at T2. The mean of the outcome changes from T1 to T2 will be compared between the intervention and control arms using a linear model. To investigate the durability of the treatment effect, outcome changes from T1 to T3 and T4 will also be compared between the two arms. We will account for the aforementioned correlations by clustering data based on CID in the generalised estimation equations (GEE). To help interpret the effect size, Cohen’s d between the arms will be calculated.

Missing values

A complete case analysis will be performed, which will only include participants with no missing values in the variables of interest. Sensitivity analysis for missing values will be conducted by either inverse probability-weighted GEE103 or multiple imputation.

Subgroup analysis

Effects of the intervention will be investigated by subgroups, as the observed effect may vary depending on the specific population. Participants will be divided by the types of primarily used substance, gender, previous and current utilisation of other SUD treatment, high and low values in clinical characteristics at T1 (eg, per cent days of abstinence, ASI drug use composite score, URICA readiness score, and cognitive function). Specifically, based on previous studies which showed that treatment effectiveness varied depending on baseline severity levels,104 105 we hypothesised that participants assigned to tele-Indo-DARPP with more severe levels of substance use at T1 would report more increase in days of abstinence at T2, T3, and T4.

Implementation evaluation

χ² tests and t-tests will be performed to compare retention in treatment and treatment satisfaction between the arms, exclusively for participants who are already receiving SUD treatment at T1. Group cohesion and Indo-DARPP attendance will be descriptively reported by means and SD. For cost-effectiveness analysis, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios will be calculated, which will yield costs per QALY and abstinent year. Feedback interviews will be transcribed, and thematic analysis will be conducted.

Compensations

Participants in both the control and intervention groups will receive 300 000 IDR (~US$21.3) to compensate for their transportation to treatment sites for TAU throughout the 12 weeks, and 98 000 IDR (≈US$7.0) every time they completed an online video assessment as compensation for internet data and 2-hour data collection. Participants from the intervention group will further receive internet mobile data equivalent to 50 000 IDR (≈US$3.5) before the first session of tele-Indo-DARPP, and subsequently every time they attend four sessions of tele-Indo-DARPP. For providers, compensation of 170 000 IDR (≈US$12.1) and 150 000 IDR (≈US$10.7) will be provided for each tele-Indo-DARPP session to the facilitator and cofacilitator, respectively.

Data monitoring

Data on adverse events, including hospitalisation, arrest, and death, will be collected from the participants’ treating psychiatrists or medical staff. In addition, participants will be interviewed at T2 to determine whether they have experienced any subjective harmful effects (eg, withdrawal syndrome, increased cravings) after joining Indo-DARPP. An independent data monitoring committee will not be convened, as the study involves short-term, non-invasive psychotherapeutic intervention. No interim analysis was planned due to the short duration of the intervention. Completeness and accuracy of data collection will be checked by Japanese coinvestigators, and there will be no auditing process by independent investigators.

Data publication

The results of the study will be published in scientific publications and reported to relevant government bodies in Indonesia to advocate adopting the treatment module.

Ethical consideration and dissemination

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia (approval number: KET-1175/2019) and the Ethics Committee of the Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine, Kyoto University (approval number: C1483). The study protocol was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trial Registry (UMIN-CTR) (registry number: UMIN000042186).

The consent process will be conducted carefully to ensure that all potential participants fully understand the research objectives, procedures, risks, benefits, costs, and alternatives. It will be emphasised that study participation is voluntary, and consent can be withdrawn at any time before publication. We will allocate participants to treatment arms only when written informed consent for participation is obtained. Likewise, urine specimens will only be collected if written informed consent for urine collection is obtained. Participants will not be influenced when deciding on study participation and/or urine collection. Personal data will be protected by separating the study data from the participants’ identifiable information. To quickly respond to adverse events arising when outpatient visits are not possible, a dedicated phone number and WhatsApp account for the study will be opened to ease communication with the research team. Participants will be instructed to text or call when experiencing adverse events. Importantly, written agreement will be obtained from participants to never share others’ information with any third party. This regulation will be enforced both during and outside tele-Indo-DARPP sessions, in any medium, including video conference and group chat.

The results of this study will be disseminated via peer-reviewed journals and international academic conferences. Depending on trial outcomes, Indo-DARPP will be advocated to the Indonesian government for adoption as a nationwide formal treatment programme.

Patient and public involvement

Patient feedback during the pilot study was incorporated into the Indo-DARPP module design. In addition, patients and/or the public will not be involved in conducting, reporting, or disseminating this study.

Discussion

At the time of writing, nine RCTs from LMICs had reported the effectiveness of digital delivery of interventions for SUD. The used formats were telephone calls,106–109 webpages,110–112 and mobile applications.100 113 However, no study in LMICs has so far investigated the effectiveness of video conference-based psychotherapy. The latter may facilitate honest, interactive discussions on personal substance use and cravings, founded on better rapport between providers and patients,114 all of which are integral to CBT for SUD. One meta-analysis concluded that web-based mental health interventions had better retention rates and treatment outcomes when therapists were synchronously involved.115

This study has several strengths. This will be the first RCT to investigate the effectiveness of video conference-based psychotherapy in any LMIC, as well as the first study to establish quality evidence on psychotherapy for SUD in Indonesia. Recruitment will be done throughout multiple levels of care, that is, tertiary (referral hospitals), primary (Puskesmas), and community (rehabilitation centres). The latter have extensive reach encompassing all major Indonesian islands, and social media advertising will facilitate recruitment across the nation. While effectiveness of CBT is the primary outcome, the study allows examinations of real-world implementation and cost-effectiveness in a hybrid effectiveness-implementation design.64 This is particularly true in Puskesmas, where the providers will be general practitioners, and in rehabilitation centres, where the providers will be peer counsellors. This pragmatic RCT aims to mimic usual clinical practice, and we hope that the results may be used to inform decision-making by patients, providers and policymakers.116

This study has several limitations. All data from participants will be self-reported and prone to recall and social desirability bias. Urine tests will be performed to corroborate subjective data but will not constitute a full validation, as they will only be performed once to represent substance-detectable period. The test was planned only at T2 to improve feasibility for participants and reduce the risk of drop-outs. Control conditions will be heterogeneous, as the study will include participants who use various substances at multiple sites, where TAU differs or may not even be provided. Variability in the providers’ background may create inconsistency in CBT delivery, even though training and treatment manuals will be introduced to standardise care. Treatment delivery via online video-conferencing might have poor generalisability towards people with low internet literacy, as well as people in low socioeconomic strata who cannot afford smartphones, although entry-level Android-based smartphones (less than US$100) are available nationwide in Indonesia. Psychotherapy will be provided in Bahasa Indonesia; hence, its effectiveness would not be generalisable to people with limited proficiency in the language.

Efforts to establish evidence-based treatment for SUD should be scaled up in Indonesia and LMICs in general, where effectiveness data are sparse. The proposed study may present high-quality evidence, and a successful outcome may result in a new SUD treatment module in Indonesia, paving the way for the adoption of Indo-DARPP into the national guidelines. We hope that our efforts may further promote a comprehensive healthcare approach, as opposed to repressive antidrug policies, for the SUD population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Takashi Kawamura for his valuable comments on the study design.

Footnotes

CY, KS, EH and YO contributed equally.

Contributors: CY, KS and YO conceptualised the study. CY, KS, EH and YO are the main developers of the Indo-DARPP module, designed study methodology, invited and coordinated site investigators, conducted training of providers, wrote the protocol and reviewed and edited the final manuscript. EB, VR, PA and AP helped in module development, study design, training of providers and site coordination. TS provided biostatistical and epidemiological supervision. TM provided the original SMARPP module and clinical input and perspectives to improve study quality. RS supervised the whole study and procured grants. CY and RS are the principal investigators of the grants. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Japan-ASEAN Platform for Transdisciplinary Studies project of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies of Kyoto University, Research Unit for Development of Global Sustainability of Kyoto University and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (Grant number JP19K24256).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.GBD 2016 Alcohol and Drug Use Collaborators . The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry 2018;5:987–1012. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators . Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1223–49. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S, et al. Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction 2018;113:1905–26. 10.1111/add.14234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes . World drug report 2020. Vienna: UNODC, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connery HS, McHugh RK, Reilly M, et al. Substance use disorders in global mental health delivery: epidemiology, treatment gap, and implementation of evidence-based treatments. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2020;28:316–27. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lora A, Hanna F, Chisholm D. Mental health service availability and delivery at the global level: an analysis by countries' income level from who's mental health atlas 2014. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2017:1–12. 10.1017/S2045796017000075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawson RA, Woody G, Kresina TF, et al. The globalization of addiction research: capacity-building mechanisms and selected examples. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2015;23:147–56. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degenhardt L, Glantz M, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Estimating treatment coverage for people with substance use disorders: an analysis of data from the world mental health surveys. World Psychiatry 2017;16:299–307. 10.1002/wps.20457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puslitdatin Badan Narkotika Nasional . Indonesia drugs report 2019. Jakarta: Badan Narkotika Nasional, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puslitdatin Badan Narkotika Nasional . Survei penyalahgunaan dan peredaran gelap narkoba tahun 2018 [Survey of illicit drug abuse and black marketing in 2018]. Available: https://perpustakaan.bnn.go.id/sites/default/files/Buku_Digital_2020-10/Survei%20Penyalahgunaan%20Dan%20Peredaran%20Gelap%20Narkoba%20Tahun%202018%20%28%20BNN%20-%20LIPI%29.pdf [Accessed 4 Dec 2020].

- 11.Puslitdatin Badan Narkotika Nasional . Ringkasan eksekutif hasil survei BNN tahun 2016 [Executive summary of survey result by BNN in 2016]. Jakarta: Badan Narkotika Nasional, 2017. https://www.issup.net/files/2017-10/penelitian%20prevelansi%20UI%20dan%20BNN.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Ansari B, Thow A-M, Day CA, et al. Extent of alcohol prohibition in civil policy in Muslim majority countries: the impact of globalization. Addiction 2016;111:1703–13. 10.1111/add.13159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Media Indonesia . Banyak narkoba jenis baru masuk ke Indonesia [A lot of new types of illicit drugs has entered Indonesia]. Media Indonesia, 2020. Available: https://mediaindonesia.com/politik-dan-hukum/325442/banyak-narkoba-jenis-baru-masuk-ke-indonesia [Accessed December 4, 2020].

- 15.Kosten TR, Petrakis IL. The hidden epidemic of opioid overdoses during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:585. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia . Aplikasi komunikasi data [Data communication application]. {Kementerian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia}, 2020. Available: https://komdat.kemkes.go.id/lama/index.php [Accessed January 10, 2021].

- 17.Idaiani S, Riyadi EI. Sistem kesehatan jiwa di indonesia: Tantangan untuk memenuhi kebutuhan [Indonesian mental health system: The challenge to fulfill needs]. Jurnal Penelitian dan Pengembangan Pelayanan Kesehatan 2018:70–80. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marastuti A, Subandi MA, Retnowati S, et al. Development and evaluation of a mental health training program for community health workers in Indonesia. Community Ment Health J 2020;56:1248–54. 10.1007/s10597-020-00579-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wammes JJG, Siregar AY, Hidayat T, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of methadone maintenance therapy as HIV prevention in an Indonesian high-prevalence setting: a mathematical modeling study. Int J Drug Policy 2012;23:358–64. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afriandi I, Siregar AYM, Meheus F, et al. Costs of hospital-based methadone maintenance treatment in HIV/AIDS control among injecting drug users in Indonesia. Health Policy 2010;95:69–73. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma M, Oppenheimer E, Saidel T, et al. A situation update on HIV epidemics among people who inject drugs and national responses in south-east Asia region. AIDS 2009;23:1405–13. 10.1097/qad.0b013e32832bd7c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarasvita R, Tonkin A, Utomo B, et al. Predictive factors for treatment retention in methadone programs in Indonesia. J Subst Abuse Treat 2012;42:239–46. 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rumah Sakit Ketergantungan Obat . Laporan Kegiatan Tahunan (Annual Report) 2007. {Rumah Sakit Ketergantungan Obat}, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iskandar S, van Crevel R, Hidayat T, et al. Severity of psychiatric and physical problems is associated with lower quality of life in methadone patients in Indonesia. Am J Addict 2013;22:425–31. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00334.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herindrasti VLS, Drug-free A. Tantangan Indonesia dalam penanggulangan penyalahgunaan narkoba [Drug-free ASEAN 2025: Indonesia’s challenge in tackling drugs abuse]. Jurnal Hubungan Internasional 2025;2018:19–33. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kramer E, Stoicescu C. An uphill battle: a case example of government policy and activist dissent on the death penalty for drug-related offences in Indonesia. Int J Drug Policy 2021;92:103265. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McHugh RK, Hearon BA, Otto MW. Cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010;33:511–25. 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magill M, Ray LA. Cognitive-Behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2009;70:516–27. 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bigelow GE, Silverman K. Theoretical and empirical foundations of contingency management treatments for drug abuse, 1999. Available: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1999-02363-001

- 30.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. Guilford Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change. 2nd ed, 2002: 428. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alan Marlatt G, Gordon JR. Relapse prevention: maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Agrawal S. Randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral motivational intervention in a group versus individual format for substance use disorders. Psychol Addict Behav 2009;23:672–83. 10.1037/a0016636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Group therapy for substance use disorders: a motivational cognitive-behavioral approach. Guilford Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myers B. 11 - Psychotherapy for substance use disorders. In: Stein DJ, Bass JK, Hofmann SG, eds. Global Mental Health and Psychotherapy. Academic Press, 2019: 241–56. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heijdra Suasnabar JM, Hipple Walters B. Community-Based psychosocial substance use disorder interventions in low-and-middle-income countries: a narrative literature review. Int J Ment Health Syst 2020;14:74. 10.1186/s13033-020-00405-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph J, Basu D. Efficacy of brief interventions in reducing hazardous or harmful alcohol use in middle-income countries: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Alcohol Alcohol 2017;52:56–64. 10.1093/alcalc/agw054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Preusse M, Neuner F, Ertl V. Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions targeting hazardous and harmful alcohol use and alcohol-related symptoms in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:768. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ögel K, Coskun S. Cognitive behavioral therapy-based brief intervention for volatile substance misusers during adolescence: a follow-up study. Subst Use Misuse 2011;46 Suppl 1:128–33. 10.3109/10826084.2011.580233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Min Z, Xu L, Chen H, et al. A pilot assessment of relapse prevention for heroin addicts in a Chinese rehabilitation center. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2011;37:141–7. 10.3109/00952990.2010.538943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wechsberg WM, Krupitsky E, Romanova T, et al. Double jeopardy--drug and sex risks among Russian women who inject drugs: initial feasibility and efficacy results of a small randomized controlled trial. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2012;7:1. 10.1186/1747-597X-7-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pan S, Jiang H, Du J, et al. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy on opiate use and retention in methadone maintenance treatment in China: a randomised trial. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127598. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alammehrjerdi Z, Briggs NE, Biglarian A, et al. A randomized controlled trial of brief cognitive behavioral therapy for regular methamphetamine use in methadone treatment. J Psychoactive Drugs 2019;51:280–9. 10.1080/02791072.2019.1578445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The future of mental health care in Indonesia. Available: https://www.insideindonesia.org/the-future-of-mental-health-care-in-indonesia [Accessed 10 Jan 2021].

- 45.The Jakarta Post . Traffic jam: Jakarta roads remain one of world’s most congested. Available: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/02/06/traffic-jam-jakarta-roads-remain-one-of-worlds-most-congested.html [Accessed 10 Jan 2021].

- 46.Mannarini S, Boffo M, Anxiety BM. Anxiety, bulimia, drug and alcohol addiction, depression, and schizophrenia: what do you think about their aetiology, dangerousness, social distance, and treatment? a latent class analysis approach. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:27–37. 10.1007/s00127-014-0925-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staton-Tindall M, Havens JR, Webster JM. METelemedicine: a pilot study with rural alcohol users on community supervision: a pilot study with rural alcohol users. J Rural Health 2014;30:422–32. 10.1111/jrh.12076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baca CT, Manuel JK. Satisfaction with long-distance motivational interviewing for problem drinking. Addict Disord Their Treat 2007;6:39–41. 10.1097/01.adt.0000210708.57327.28 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leo JAD, Lamb K, LaRowe S, et al. A brief behavioral telehealth intervention for veterans with alcohol misuse problems in Va primary care. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;140:Complete: e45. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tarp K, Bojesen AB, Mejldal A, et al. Effectiveness of optional Videoconferencing-Based treatment of alcohol use disorders: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 2017;4:e38. 10.2196/mental.6713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.King VL, Stoller KB, Kidorf M, et al. Assessing the effectiveness of an Internet-based videoconferencing platform for delivering intensified substance abuse counseling. J Subst Abuse Treat 2009;36:331–8. 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.King VL, Brooner RK, Peirce JM, et al. A randomized trial of web-based videoconferencing for substance abuse counseling. J Subst Abuse Treat 2014;46:36–42. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boumparis N, Schulte MHJ, Riper H. Digital mental health for alcohol and substance use disorders. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2019;6:352–66. 10.1007/s40501-019-00190-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Araya R, et al. Digital technology for treating and preventing mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:486–500. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30096-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin LA, Casteel D, Shigekawa E, et al. Telemedicine-delivered treatment interventions for substance use disorders: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat 2019;101:38–49. 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boumparis N, Karyotaki E, Schaub MP, et al. Internet interventions for adult illicit substance users: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2017;112:1521–32. 10.1111/add.13819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boumparis N, Loheide-Niesmann L, Blankers M, et al. Short- and long-term effects of digital prevention and treatment interventions for cannabis use reduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;200:82–94. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fu Z, Burger H, Arjadi R, et al. Effectiveness of digital psychological interventions for mental health problems in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:851–64. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30256-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.The Mobile Economy Asia Pacific 2020 - The Mobile Economy. Available: https://www.gsma.com/mobileeconomy/asiapacific/ [Accessed 10 Jan 2021].

- 60.Shore JH, Schneck CD, Mishkind MC. Telepsychiatry and the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic-current and future outcomes of the rapid virtualization of psychiatric care. JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77:1211-1212. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Molfenter T, Roget N, Chaple M, et al. Use of telehealth in substance use disorder services during and after COVID-19: online survey study. JMIR Ment Health 2021;8:e25835. 10.2196/25835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adepoju P. Africa turns to telemedicine to close mental health gap. Lancet Digit Health 2020;2:e571–2. 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30252-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Minas H. Mental health in a post-pandemic ASEAN. The ASEAN, 2021: 37–8. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50:217–26. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific . Guidance for community-based treatment and care services for people affected by drug use and dependence in Southeast Asia. United national office on drugs and crime, 2014. Available: https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific/cbtx/cbtx_guidance_EN.pdf

- 66.Nordfjærn T. Relapse patterns among patients with substance use disorders. J Subst Use 2011;16:313–29. 10.3109/14659890903580482 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brecht M-L, Herbeck D. Time to relapse following treatment for methamphetamine use: a long-term perspective on patterns and predictors. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;139:18–25. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tosh G, Soares-Weiser K, Adams CE. Pragmatic vs explanatory trials: the pragmascope tool to help measure differences in protocols of mental health randomized controlled trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2011;13:209–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matsumoto T, Imamura F, Kobayashi O, et al. [Development and evaluation of a relapse prevention tool for drug-abusing delinquents incarcerated in a juvenile classification home: a self-teaching workbook for adolescents, the "SMARPP-Jr]. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi 2009;44:121–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Obert JL, McCann MJ, Marinelli-Casey P, et al. The matrix model of outpatient stimulant abuse treatment: history and description. J Psychoactive Drugs 2000;32:157–64. 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kondo A, Ide M, Takahashi I, et al. [Evaluation of the relapse prevention program for substance abusers called "TAMARPP" at mental health and welfare center]. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi 2014;49:119–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Matsumoto T, Chiba Y, Imamura F, et al. Possible effectiveness of intervention using a self-teaching workbook in adolescent drug abusers detained in a juvenile classification home. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011;65:576–83. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02267.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tanibuchi Y, Matsumoto T, Imamura F, et al. [Efficacy of the Serigaya Methamphetamine Relapse Prevention Program (SMARPP): for patients with drug use disorder: A study on factors influencing 1-year follow-up outcomes]. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi 2016;51:38–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rawson RA, Huber A, McCann M, et al. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches during methadone maintenance treatment for cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:817–24. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carroll KM, Kiluk BD, Nich C, et al. Toward empirical identification of a clinically meaningful indicator of treatment outcome: features of candidate indicators and evaluation of sensitivity to treatment effects and relationship to one year follow up cocaine use outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;137:3–19. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, et al. The timeline Followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:134–44. 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, et al. Temporal stability of the timeline Followback interview for alcohol and drug use with psychiatric outpatients. J Stud Alcohol 2004;65:774–81. 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis 1980;168:26–33. 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD. Concurrent validity of the addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis 1983;171:606–10. 10.1097/00005053-198310000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hendriks VM, Kaplan CD, van Limbeek J, et al. The addiction severity index: reliability and validity in a Dutch addict population. J Subst Abuse Treat 1989;6:133–41. 10.1016/0740-5472(89)90041-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carise D. Addiction Severity Index Treatnet Version: Manual and Question by Question “Q by Q” Guide. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res 2013;22:1717–27. 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rand K, Arnevik EA, Walderhaug E. Quality of life among patients seeking treatment for substance use disorder, as measured with the EQ-5D-3L. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2020;4:92. 10.1186/s41687-020-00247-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goranitis I, Coast J, Day E, et al. Measuring health and broader well-being benefits in the context of opiate dependence: the psychometric performance of the ICECAP-A and the EQ-5D-5L. Value Health 2016;19:820–8. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Purba FD, Hunfeld JAM, Iskandarsyah A, et al. The Indonesian EQ-5D-5L value set. Pharmacoeconomics 2017;35:1153–65. 10.1007/s40273-017-0538-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McConnaughy EA, Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. Stages of change in psychotherapy: measurement and sample profiles. Group Dyn 1983;20:368–75. [Google Scholar]

- 88.DiClemente CC, Schlundt D, Gemmell L. Readiness and stages of change in addiction treatment. Am J Addict 2004;13:103–19. 10.1080/10550490490435777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief cope. Int J Behav Med 1997;4:92–100. 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Berg MK, Hobkirk AL, Joska JA, et al. The role of substance use coping in the relation between childhood sexual abuse and depression among methamphetamine users in South Africa. Psychol Trauma 2017;9:493–9. 10.1037/tra0000207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Derogatis LR, Savitz KL. The SCL-90-R, brief symptom inventory, and matching clinical rating scales. In: Maruish ME, ed. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, xvi. Mahwah: NJ, US, 1999: 679–724. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bergly TH, Nordfjærn T, Hagen R. The dimensional structure of SCL-90-R in a sample of patients with substance use disorder. J Subst Use 2014;19:257–61. 10.3109/14659891.2013.790494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ryan JJ, Geisser ME. Validity and diagnostic accuracy of an alternate form of the Rey auditory verbal learning test. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 1986;1:209–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Potvin S, Pelletier J, Grot S, et al. Cognitive deficits in individuals with methamphetamine use disorder: a meta-analysis. Addict Behav 2018;80:154–60. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rosa B, Oliveira J, Gamito P. Cognitive improvement via mHealth for patients recovering from substance use disorder. In: International workshops on ICTs for improving patients rehabilitation research techniques. Springer International Publishing, 2017: 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res 2003;121:31–49. 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann 1979;2:197–207. 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Boden MT, Kimerling R, Jacobs-Lentz J, et al. Seeking safety treatment for male veterans with a substance use disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Addiction 2012;107:578–86. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03658.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Marziliano A, Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, et al. Measuring cohesion and self-disclosure in psychotherapy groups for patients with advanced cancer: an analysis of the psychometric properties of the group therapy experience scale. Int J Group Psychother 2018;68:407–27. 10.1080/00207284.2018.1435284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liang D, Han H, Du J, et al. A pilot study of a smartphone application supporting recovery from drug addiction. J Subst Abuse Treat 2018;88:51–8. 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kish L. Survey sampling. New York: Wiley, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Takano A, Miyamoto Y, Shinozaki T, et al. Effect of a web-based relapse prevention program on abstinence among Japanese drug users: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Subst Abuse Treat 2020;111:37–46. 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Iachina M. The evaluation of the performance of IPWGEE, a simulation study. Commun Stat Simul Comput 2009;38:1212–27. 10.1080/03610910902859566 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Gordon LT, et al. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for ambulatory cocaine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51:177–87. 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030013002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rosenblum A, Magura S, Kayman DJ, et al. Motivationally enhanced group counseling for substance users in a soup kitchen: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;80:91–103. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fernandes S, Ferigolo M, Benchaya MC, et al. Brief motivational intervention and telemedicine: a new perspective of treatment to marijuana users. Addict Behav 2010;35:750–5. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wongpakaran T, Petcharaj K, Wongpakaran N, et al. The effect of telephone-based intervention (TBI) in alcohol abusers: a pilot study. J Med Assoc Thai 2011;94:849–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Signor L, Pierozan PS, Ferigolo M, et al. Efficacy of the telephone-based brief motivational intervention for alcohol problems in Brazil. Braz J Psychiatry 2013;35:254–61. 10.1590/1516-4446-2011-0724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Marasinghe RB, Edirippulige S, Kavanagh D, et al. Effect of mobile phone-based psychotherapy in suicide prevention: a randomized controlled trial in Sri Lanka. J Telemed Telecare 2012;18:151–5. 10.1258/jtt.2012.SFT107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Christoff AdeO, Boerngen-Lacerda R. Reducing substance involvement in college students: a three-arm parallel-group randomized controlled trial of a computer-based intervention. Addict Behav 2015;45:164–71. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Baldin YC, Sanudo A, Sanchez ZM. Effectiveness of a web-based intervention in reducing binge drinking among nightclub patrons. Rev Saude Publica 2018;52:2. 10.11606/s1518-8787.2018052000281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tiburcio M, Lara MA, Martínez N, et al. Web-Based intervention to reduce substance abuse and depression: a three arm randomized trial in Mexico. Subst Use Misuse 2018;53:2220–31. 10.1080/10826084.2018.1467452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhu Y, Jiang H, Su H, et al. A newly designed Mobile-Based computerized cognitive addiction therapy APP for the improvement of cognition impairments and risk decision making in methamphetamine use disorder: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e10292. 10.2196/10292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rush KL, Howlett L, Munro A, et al. Videoconference compared to telephone in healthcare delivery: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform 2018;118:44–53. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklícek I, et al. Internet-Based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2007;37:319–28. 10.1017/S0033291706008944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Patsopoulos NA. A pragmatic view on pragmatic trials. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2011;13:217–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-050259supp001.pdf (84.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050259supp002.pdf (115.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050259supp003.pdf (82.4KB, pdf)