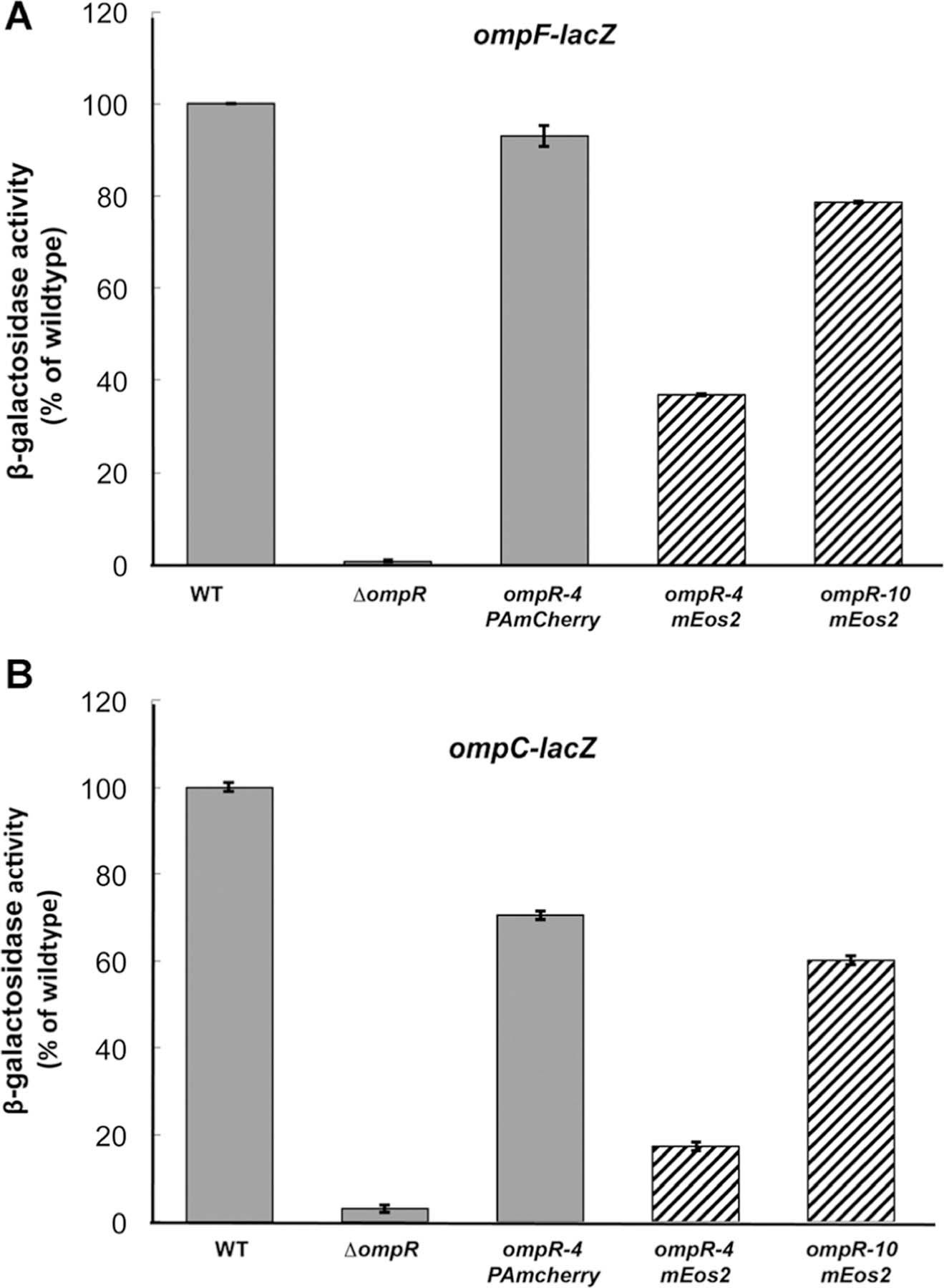

Fig. 1.

Comparison of OmpR–PAmCherry with OmpR-mEos and wildtype OmpR. MH513 and MH225 are bacterial strains containing a chromosomal ompF-lacZ (A) or ompC-lacZ (B) transcriptional fusion, respectively. Wildtype OmpR (column 1) represented 100% and the other backgrounds were normalized to it. In the ompR null strain (ompR101), there was no activation of ompF or ompC. The PAmCherry fusion was 93% as active as the wildtype, when a 16 amino acid linker, GGSGx4, was placed between the 3ʹ end of ompR and the beginning of PAmCherry. Its activity was higher than the mEos2 fusion that contained the same linker length (striped column 4, 37%), but a longer linker (40 amino acids, GGSGx10) improved activity to 79% of the wildtype (column 5). Similarly, at ompC, the PAmCherry fusion was 71% of the wildtype activity and better than the mEos2 fusion (17% with a 16 amino acid linker and 60% with a 40 amino acid linker). The photoactivatable fusion affected ompC activity more than ompF as we have observed with other ompR mutants38 as well as with envZ photoactivatable fusions.2