Abstract

Bipolar disorder (BD) might be associated with higher infection rates of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) which in turn could result in worsening the clinical course and outcome. This may be due to a high prevalence of somatic comorbidities and an increased risk of delays in and poorer treatment of somatic disease in patients with severe mental illness in general. Vaccination is the most important public health intervention to tackle the ongoing pandemic. We undertook a systematic review regarding the data on vaccinations in individuals with BD. Proportion of prevalence rates, efficacy and specific side effects of vaccinations and in individuals with BD were searched. Results show that only five studies have investigated vaccinations in individuals with BD, which substantially limits the interpretation of overall findings. Studies on antibody production after vaccinations in BD are very limited and results are inconsistent. Also, the evidence-based science on side effects of vaccinations in individuals with BD so far is poor.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, Vaccination, COVID-19, Infectious diseases, Systematic review

1. Introduction

Individuals with severe mental illness (SMI), such as bipolar disorder (BD), are more liable to the development of major somatic comorbidities (Chesney et al., 2014; Colomer et al., 2020; M. De Hert et al., 2011; Harris and Barraclough, 1998; Kessing et al., 2021) resulting in a substantially reduced (8–12 years) life expectancy compared to the general population (Chesney et al., 2014; Nordentoft et al., 2013). Patients with BD have an increased mortality rate of approximately 2.5. The main causes of death are somatic disorders, albeit unnatural deaths are increased to a large degree when compared to the general population (Hayes et al., 2015). The leading cause of mortality in BD are cardiovascular disorders, which are directly related to the metabolic syndrome, including obesity and diabetes mellitus (Correll et al., 2017; M. De Hert et al., 2011; Vancampfort et al., 2015, 2016). These are also among the predictors of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) related mortality.

Heggelund et al. (2020) demonstrated that cardio-respiratory functioning is significantly reduced in BD, with 20–40% of patients with an affective or non-affective psychosis demonstrating an aerobic capacity below that required for functional daily living. In this context, infection with SARS-CoV2 is also common (Wang et al., 2020) and accordingly, the risk of COVID-19 in BD is further increased by disproportionately high rates of factors associated with COVID-19 mortality, such as obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome (Maripuu et al., 2021). Importantly, also infectious diseases, such as pneumonia and pneumococcal disease, are more frequent in SMI compared to the general population (Seminog and Goldacre, 2013).

Moreover, individuals with BD may also be more vulnerable to certain complications, pharmacologic interactions, and relapse in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (Hernandez-Gomez et al., 2021; Stefana et al., 2020). As a consequence, COVID-19 mortality is higher in patients with BD (Wang et al., 2021). In a recent analysis of electronic health records of 61 million adults in the USA, individuals with mental disorders (including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, BD, major depressive disorder and schizophrenia) were at increased risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization and related mortality (Wang et al., 2021). Individuals with BD had a 7.69 (95% CI 7.05–8.40) adjusted OR (AOR) for COVID-19 infections than individuals without a mental disorder, with an estimated death rate of 8.5% vs. 4.7% in individuals without mental illness.

Long-term mood stabilizing medication might also impact on the risk for respiratory infections in BD. A recent large register-based study found that rates of respiratory infection were significantly higher while on valproate medication than during periods off valproate. By contrast, lithium treatment decreased the risk of respiratory infections (Landén et al., 2021).

In general, there is some data showing that individuals with SMI might be at increased risk for COVID-19. A recent study, including 69,8 million health records in the USA, found a psychiatric diagnosis in the previous year associated with a higher incidence of COVID-19 diagnosis (relative risk 1•65, 95% CI 1•59–1•71; p<0•0001). The risk was independent of known physical health risk factors for COVID-19, but confounding socioeconomic factors could not be excluded by the authors (Taquet et al., 2021). In addition, a national register study in South Korea found that patients with SMI had a slightly higher risk for severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19 defined as death, admission to the intensive care unit or invasive ventilation (Lee et al., 2020). In line with this, presence of a mood disorder prior to admission to hospital in individuals infected with SARSCoV2 was associated with greater in-hospital mortality risk beyond hospital day 12 and were at increased risk of need for postacute care (Castro et al., 2021). Beside somatic variables, SARSCoV2 infection might also negatively impact upon the mental status of people with pre-existing SMI (Barber et al., 2020).

All the arguments above suggest that patients with BD should be prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination, just as any other patient with severe illness. The first vaccines against COVID-19, which is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), were authorized by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the USA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in December 2020. While rapid vaccination will reduce the burden of this pandemic, unfortunately there are major challenges worldwide still hindering the campaign of vaccinating and the achievement of population-wide immunity. Recently, De Picker et al. (2021), in a joint recommendation of professionals, patients, and families, advocated for explicit inclusion of both inpatients and outpatients with SMI in priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination.

Consequently, this work aimed to elucidate the risk and treatment effect of COVID-19 in BD and research on vaccinations in individuals with BD by performing a systemic literature search. Literature on vaccination against COVID-19, apart from phase II and III trial data, was expected to be low at the time of writing the review. As we are convinced that we can learn from previous studies concerning vaccination in individuals with BD and apply this knowledge to the COVID-19 pandemic, we focused on studies dealing with vaccines other than the COVID-19 vaccines in individuals with BD.

2. Experimental procedures

The literature was systemically screened to establish whether there were differences between individuals with BD and mentally healthy subjects in: 1. prevalence of vaccination rates; 2. efficacy and antibody production after vaccination; and 3. side effects of vaccination. In addition, we looked for data exploring pharmacokinetic or -dynamic interactions between psychopharmacological treatment of individuals with BD and vaccinations. The research was conducted in June 2021 and included articles published until that date. The terms “vaccin* AND bipolar”, “vaccin* AND depress*”, “vaccine* AND mania” and “vaccine* AND manic” were systematically searched in the databank PubMed and Embase by the authors NB and FF independently, and by ER as an independent supervisor. Furthermore, the bibliographies of included studies and recent reviews were investigated. The search was not limited to specific languages. Only articles with the specification that in the sample individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder were included, were considered for the review.

3. Results

3.1. Vaccinations and BD

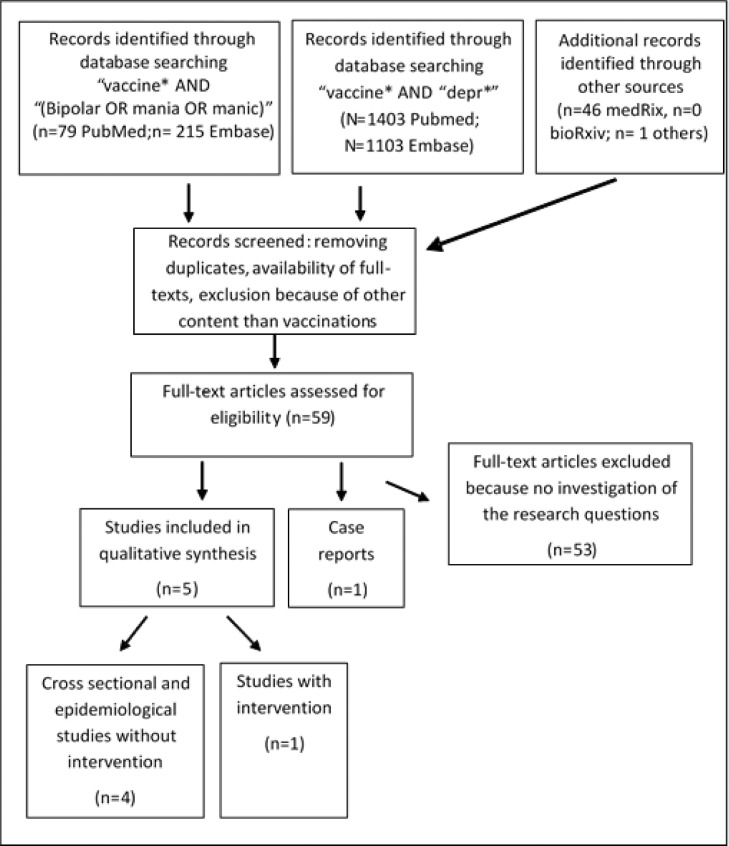

The detailed results of the search and studies and literature included is shown in Figure 1 . Five studies were included in the qualitative analysis as well as one case report.

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart of literature search on vaccination and BD.

3.2. Prevalence rates

No studies were found reporting data about prevalence rates of vaccination in BD in general. One very recent study found different pre-pandemic psychiatric diagnoses, including BD, not associated with vaccination hesitancy in a large UK-wide cohort study, including 11,955 people (Batty et al., 2021). In the analyses, 324 individuals with pre-existing anxiety, 368 with pre-existing depression, 111 with pre-existing “other mental health condition, including BD and 491 with any mental condition were included.

3.3. Antibody production after vaccinations

No studies have investigated the production of antibodies in individuals with BD after vaccination for COVID-19. Three studies dealt with the immunogenicity in general of vaccinations in individuals with BD.

In a study from 1994, 100 hepatitis-B-virus serologically negative patients with mania, uni- and bipolar depression, or schizophrenia were vaccinated with Recombivax HB (Merck Sharp & Dohme) and received three intramuscular 20 mcg doses in the deltoid region at 0, 1, and 6 months (Russo et al., 1994). In sum, 73 of the patients did not respond to the vaccination and response rate was lower than that reported with the same vaccine on different groups of subjects at that time (Miskovsky et al., 1991). There was no further stratification of diagnoses in the study, so data of individuals with mania were specified.

In an older study, 25 individuals with BD and 88 individuals with schizophrenia were assessed for anti-tetanus antibodies. All had been vaccinated in the last ten years against tetanus disease. Twelve percent of individuals with BD and eight percent of individuals with schizophrenia had antibodies below the limit of 0,06Ul/ml, while 4.6% of individuals with schizophrenia had antibody levels above the range. In individuals with schizophrenia, higher age correlated significantly with lower immune defenses (De Beaurepaire et al., 1994).

A more recent study by Ford et al. (2019) tested the hypothesis that individuals with a mood disorder display reduced humoral immunity (IgG antibodies in plasma) to measles. Participants with a mood disorder were less likely to be seropositive compared to controls (p = 0.015, adjusted OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.31–0.88) and age was a predictor of serostatus. Individuals with unipolar depression were less likely to be seropositive compared to healthy controls while individuals with BD did not differ from healthy controls. However, these negative results in the BD group were assumed to be due to a reduced statistical power, given by the smaller sample size in the BD versus the major depressive disorder group (Ford et al., 2019).

For further details see also Table 1 .

Table 1.

Studies investigating vaccinations in bipolar disorder.

| Population | Study aim/ Primary outcome measure | Study design | Bipolar specific measures | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russo et al., 1994 | BD n = 22, SZ n = 78 | Efficacy of Hepatitis B vaccination/ Hbs antibody concentration | One group with 20 µg Recombivax HB at 0,1 and 6 months, comparison to other studies with other target groups | Pre-existing diagnosis | 73% showed no response Lower response than comparison-study |

| Ford et al., 2018 | BD n = 64, MDD depressed n = 85, MDD remitted n = 82, HC n = 202 | Immunity against measles with USA typical vaccination program/ Measles IgG antibodies | three patient groups, one control group, no intervention | Age m = 33.2 (8.3) years, Age of onset 16.6 (5.6) years, 78.1% females Diagnosis with SCID, Symptom rating with MADRS | Immunity was lower in MDD than in HC, but no difference between BD and HC (explanation small sample size) age as predictor |

| De Beaurepaire et al., 1994 | BD n = 22, SZ n = 88 | Antitetanus antibodies in BD and SZ after vaccination | Cross-sectional, no intervention | Age m = 52,5 years, illness duration m = 23.9 years Pre-existing diagnosis | Antibodies below the limit: BD 12%, SZ 8% antibody levels above the range: SZ 4.6% |

| Leslie et al., 2017 | BD n = 5.892, AN n = 551, Anxiety disorder n = 23.462, Tic disorder n = 2.547, ADHD n = 46.640, MDD n = 13.295, OCD n = 3.222, Control groups: Open wound n = 73.290, Broken bone n = 85.151 | Association between vaccination and psychiatric disorder/ Incidence of psychiatric disorder 12 months before and 3 and 6 months after vaccination | Cross-sectional, Case-control, retrospective analysis, no intervention | Age m = 12.3+/- 2.6; female 54%, pre-existing diagnosis | BD was negatively associated with influenza vaccine in the previous 3 or 6 months (hazard ratio 0.71 and 0.84); positive associations with AN, OCD and chronic tic disorder |

| Batty et al., 2021 | 11.955 individuals, whereof 1.004 with reported pre-pandemic psychiatric diagnoses, including BD | Vaccination hesitancy in the UK | Survey April and November 2020, no intervention | Pre-existing diagnosis | Some somatic conditions but not pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses were related to a lower likelihood of being vaccine hesitant against COVID-19 |

Note: ADHD=Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, AN=Anorexia nervosa, BD=Bipolar disorder, HC Healthy controls, MDD=Major Depressive Disorder, OCD=Obsessive-compulsive disorder, SZ=Schizophrenia, UK= United Kingdom.

3.4. Side effects of vaccinations

Few data are available on side effects associated with vaccines in patients with BD or SMI. We found one study and one case report dealing with vaccination and incidence of BD (the study is also included in Table 1). A case report by Brodziński and Nasierowski (2019) was not included due to limited reliability.

Leslie et al. (2017) examined whether antecedent vaccinations were associated with the incidence of BD and also with the incidence of other psychological conditions including obsessivecompulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa, anxiety disorder, chronic tic disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and major depressive disorder in a national sample of privately insured children aged 6–15 years with the mentioned diagnoses compared to controls. Influenza vaccinations during the prior 3, 6, and 12 months were associated with incident diagnoses of obsessive–compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa and anxiety disorder. Several other vaccinations were also significantly associated with the incidence of diagnoses with OR greater than 1.40 (hepatitis A with obsessive–compulsive disorder and anorexia nervosa; hepatitis B with anorexia nervosa; meningitis with anorexia nervosa and chronic tic disorder; and anorexia nervosa with any vaccination in the prior three months). Importantly, children with BD were less likely to have received the influenza vaccine in the previous 3 or 6 months (Leslie et al., 2017). Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that the study had several limitations. Since it was a casecontrol study it is impossible to know if the vaccination increased or decreased the likelihood of psychiatric disorder or, conversely, if psychiatric disorders increased or decreased the likelihood of being vaccinated. Moreover, the authors conducted more than 180 statistical tests with no correction for multiple comparisons. They also found that vaccines increased the risk for broken bones (which was their control condition). Therefore, before drawing any inferences, these findings have to be replicated utilizing an optimized study methodology in a separate sample.

4. Discussion

The aim of this review was to summarize data on outcomes associated with vaccinations in individuals with BD. We systematically reviewed the prevalence rates, efficacy and specific side effects of vaccinations in general in individuals with BD. The focus of the review on vaccination data in individuals with BD may be considered as a proxy of what vaccinations against the SARS-CoV-2 in individuals with BD might entail. Our literature search shows that studies on the efficacy of vaccinations in general in BD are rare. There are some hints suggesting that individuals with mental disorders might have reduced antibody production after vaccinations. Importantly, only five small studies have investigated vaccinations (four of it included vaccinations other than against SARS-CoV2) in patients with BD. Furthermore, results were limited by study design and heterogeneity of studies.

Data on antibody production after vaccinations in BD is poorly explored and results are inconsistent; no data as of yet are available for vaccines against SARS-CoV2. Side effects of vaccinations in individuals with BD have so far not been researched. Importantly, recent studies suggest that not only antibody production after infection with SARS-CoV-2 but also T-cell response is probably important for immune protection against the virus. Active immunity against COVID-19 requires the formation of antigen‐specific cytotoxic T cells and synthesis of neutralizing antibodies directed against the virus (Breton et al., 2021). B cell response might be important but is not strictly required to overcome disease. This fact is in agreement with preliminary studies that have shown that in non-mentally ill subjects infected with SARS‐CoV‐2, the number of cytotoxic T cells expressing activation markers such as HLA‐DR. and CD38 increases during infection (Soresina et al., 2020). Following these considerations, individuals with mental disorders might be protected by vaccination against SARS-CoV-2, even in case of reduced antibody production, as cellular mediated immunity (by cytotoxic T cells) is supposed to play a major role. These specific concerns should be investigated in future trials and clinical experience.

Little is known about side effects of vaccinations in general in BD. Only one study found that depressive symptomatology in general lead to more frequent local side effects of vaccination in form of paresthesia and sensory disturbances (De Serres et al., 2015). There were no studies on vaccination rates in individuals with BD. Nevertheless, there are data showing that depression might be associated with lower vaccination rates, without further specification to BD. For example, one study identified depressive symptoms in the elderly population (and independent of BD) to be associated with lower vaccination rates in general (Bazargan et al., 2020). Another study showed a relationship between mental illness coincident with comorbid physical illness and lower vaccination rates (Lawrence et al., 2020). In contrast, other studies failed to find an association between depressive symptomatology and vaccination rates (Buchwald et al., 2000; Kwon et al., 2016; Batty et al., 2021); one study even reported a higher vaccination rate against influenza-A-virus H1N1 in veterans with depression (Lavela et al., 2012). To conclude, results on vaccination rates in individuals with mental disorders in general remain inconclusive.

From the data on vaccination rates in general in individuals with BD we want to span some associations to COVID-19. Patients with BD might be at higher risk for getting infected with COVID-19 and they might have a more severe disease course with increased mortality. Different factors might play a leading role. Impaired adaptive immunity and resulting higher risk of bacterial and viral infections as well as slowed wound healing (Yamagata et al., 2018; Blume et al. 2011; Cohen and Williamson 1991) may have substantial impact. Cognitive impairment, social relegation and living in environments with higher risk for infection may play a role (Yao et al., 2020; Murali and Oyebode, 2004; Shinn and Viron, 2020) and in addition to current symptomatology reduce compliance rates. Unhealthy lifestyle, which increased during pandemic, may lead to higher vulnerability for severe COVID-19 infection (Patanavanich and Glantz, 2020; Vardavas and Nikitara, 2020). Overlapping biological factors among mental disorders and COVID-19 infection might also lead to the higher risk and worse outcome of COVID-19 infection in individuals with BD (Wang et al., 2021). Especially inflammatory pathways are known to be activated in COVID-19. Moreover, depression, mania, poor sleep and severity of cognitive dysfunction seem to be related with an activation of inflammatory cascades and are associated with increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines (Anderson et al., 2014; Aric et al., 2020; Dalkner et al., 2020; Dickerson et al., 2013; Prather et al., 2021; Queissner et al., 2018). It is possible that the activation of inflammatory processes and the cytokine storm by a COVID-19 infection and the low-grade inflammation of BD might interact and worsen the clinical course of the disorder. Multimorbidity is associated with a higher risk for a severe course of COVID-19. Individuals with SMI and somatic comorbidities showed higher rates of COVID-19 associated death compared to healthy controls and to individuals with mental disorders but without somatic comorbidities (Maripuu et al., 2021). People with SMI are more likely to suffer from comorbid medical conditions which might be associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 courses (Nielsen et al., 2021). Also, in individuals with BD, somatic comorbidities such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and metabolic disorders are highly frequent (Correll et al., 2017; De Hert et al., 2009; Lackner et al., 2015; McIntyre et al., 2010; Vancampfort et al., 2016, 2015), with only minor improvement in recent years (Rødevand et al., 2019). As stigma is still a problem in individuals with BD and COVID-19, any clinical somatic symptoms might be reduced to symptoms of their mental disorder or “psychosomatic” problems, which in turn might result in lower access to health care and worse treatment for patients with severe courses of COVID-infection (Arbelo et al., 2021; Wasserman et al., 2020; M. de Hert et al., 2011).

Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 is important especially in this group of patients and has to be promoted as these patients face a higher vulnerability and probability for infection and severe course of illness. Importantly, the study on vaccination hesitancy in the UK did not find pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses to be related to a higher hesitancy against COVID-19 vaccination (Batty et al., 2021), so efforts to promote vaccination in this highly vulnerable group might be successful.

5. Limitations

For the most part, the conclusions of this review are limited by the scarcity of databased studies, the small samples and/or the poor quality of some studies. The latter was a typical issue in those publications purporting to investigate the associations between vaccination and incident cases of BD. This limitation is especially concerning given the use of misinformation and disinformation to undermine other vaccination programs, and the difficulties of rebuttal once these statements become widely disseminated. Furthermore, the most frequently used vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 so far have been mRNA based vaccines; a new technology that may not follow the immune response profiles from the vaccination techniques used previously. Furthermore, the protocol was not previously registered, since the work had to be ready quickly due to the changing situation of the pandemic and vaccination.

6. Conclusion

Our findings may have important implications for public health strategies. It is conceivable that healthcare providers could mitigate this problem by prioritizing populations of patients affected by SMI for antibody screening and vaccination. There is a lack of information on the COVID-19 vaccination in individuals with BD. Importantly, there has also been a first statement that individuals with SMI should be prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination for several reasons described (de Hert et al., 2020; De Picker et al., 2021). Nevertheless and understandably, there are many requests for prioritizing certain subgroups for early vaccination in society and usually each group has justifiable reasons for this request. In this context, we propose to include BD and other severe mental illnesses among the other important variables that are already being considered to establish a level of vaccine priority for each person. Priority in vaccinating people with SMI or BD might not only be justified for their individual well-being but also for the community, as during exacerbations of mood episodes these patients may not be able to obey public health rules of protection (in terms of masking, distance, and hygiene) resulting in exponential risk of taking the virus and spreading it out to the public.

Role of funding source

There was no study sponsor and no funding involved in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Contributors

Eva Reininghaus, Frederike Fellendorf, Nina Bonkat and Nina Dalkner designed the study and wrote the protocol.

Eva Reininghaus, Frederike Fellendorf, Nina Bonkat, Nina Dalkner managed the literature searches, analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

As the article is a review on the literature, there is generally no conflict of interest in respect to this article. Nevertheless, some of the authors had relationships with different companies or served as consultants in the last three years.

MM has served as consultant, or CME speaker for Angelini.

EV has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, Abbott, AbbVie, Angelini, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Janssen, Lundbeck, Novartis, Otsuka, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, and Takeda, outside the submitted work.

LM declares that he has received lecture honoraria from Lundbeck pharmaceutical. No other equity ownership, profit-sharing agreements, royalties, or patent.

CC has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante-ProPhase, MedInCell, Medscape, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mylan, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Servier, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka. He served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva. He has received grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He is also a stock option holder of LB Pharma.

AF is /has been a consultant and/or a speaker and/or has received research grants from Angelini, Apsen, Boheringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Doc Generici, Glaxo Smith Kline, Italfarmaco, Lundbeck, Janssen, Mylan, Neuraxpharm, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Sanofi Aventis, Sunovion, Vifor.

MB has received institutional grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), and European Commission. He served in advisory boards for GH Research, Janssen-Cilag, neuraxpharm, Novartis, Sandoz, Shire International, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, and Takeda, and received speaker honoraria for Aristo, Hexal, Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Janssen-Cilag, and Sunovion, outside the submitted work.

REN has received research grants from H. Lundbeck and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals for clinical trials, received speaking fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astra Zeneca, Janssen & Cilag, Lundbeck, Servier, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Teva A/S, and Eli Lilly and has acted as advisor to Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, and Medivir, and has acted as investigator for Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Boehringer, Compass and Sage.

RW Licht has within the preceding three years served an advisory board of Janssen Cilag and Sage and has received speaker honorarium from Astra-Zeneca, Jannsen-Cilag, Servier, Lundbeck and Teva.

No known conflicts of interest in respect to this article from all other authors.

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowledgements

References

- Anderson G., Berk M., Dean O., Moylan S., Maes M. Role of immune-inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways in the etiology of depression: therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40263-013-0119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbelo N., López-Pelayo H., Sagué M., Madero S., Pinzón-Espinosa J., Gomes-da-Costa S., Ilzarbe L., Anmella G., Llach C.D., Imaz M.L., Cámara M.M., Pintor L. Psychiatric Clinical Profiles and Pharmacological Interactions in COVID-19 Inpatients Referred to a Consultation Liaison Psychiatry Unit: a Cross-Sectional Study. Psychiatr. Q. 2021:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber S., Reed L., Syam N., Jones N., 2020. Severe mental illness and risks from COVID-19, Available from: https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/severe-mental-illness-and-risks-from-covid19/#:∼:text=People%20with%20severe%20mental%20illness,data%20that%20quantified%20these%20risks.

- Batty, G.D., Deary, I.J., Altschul, D., 2021. Pre-pandemic mental and physical health as predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: evidence from a UK-wide cohort study. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021 Apr 30:2021.04.27.21256185. doi: 10.1101/2021.04.27.21256185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bazargan M., Wisseh C., Adinkrah E., Ameli H., Santana D., Cobb S., Assari S. Influenza Vaccination among Underserved African-American Older Adults. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020;2020(2):1–9. doi: 10.1155/2020/2160894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton G., Mendoza P., Hägglöf T., Oliveira T.Y., Schaefer-Babajew D., Gaebler C., Turroja M., Hurley A., Caskey M., Nussenzweig M.C. Persistent cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Exp. Med. 2021;218(4) doi: 10.1084/jem.20202515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodziński S., Nasierowski T. Psychosis in Borrelia burgdorferi infection–part II. Psychiatr. Pol. 2019;53(3):641–653. doi: 10.12740/PP/92556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald D., Sheffield J., Furman R., Hartman S., Dudden M., Manson S. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination among Native American elders in a primary care practice. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000;160(10):1443–1448. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro M.V., Gunning F.M., McCoy T.H., Perlis R.H. Mood Disorders and outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalizations. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060842. appiajp202020060842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Williamson G.M. Stress and infectious disease in humans. Psychol. Bull. 1991;109(1):5. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer L., Anmella G., Vieta E., Grande I. Physical health in affective disorders: a narrative review of the literature. Braz. J. Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1246. S1516-44462020005037202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll C.U., Solmi M., Veronese N., Bortolato B., Rosson S., Santonastaso P., Thapa-Chhetri N., Fornaro M., Gallicchio D., Collantoni E., Pigato G., Favaro A., Monaco F., Kohler C., Vancampfort D., Ward P.B., Gaughran F., Carvalho A.F., Stubbs B. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: a large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):163–180. doi: 10.1002/wps.20420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalkner N., Reininghaus E., Schwalsberger K., Rieger A., Hamm C., Pilz R., Lenger M., Queissner R., Falzberger V.S., Platzer M., Fellendorf F.T., Birner A., Bengesser S.A., Weiss E.M., McIntyre R.S., Mangge H., Reininghaus B. C-Reactive Protein as a Possible Predictor of Trail-Making Performance in Individuals with Psychiatric Disorders. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):3019. doi: 10.3390/nu12103019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Beaurepaire R., Fattal-German M., Kramartz P., Gékière F., Bizzini B., Rioux P., Borenstein P. Etude des réactions immunitaires humorales et cellulaires dans diverses formes de pathologies psychiatriques 22 chroniques [Humoral and cellular immunologic reactions in various forms of chronic psychiatric diseases] Encephale. 1994;20(1):57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M., Correll C.U., Bobes J., Cetkovich-Bakmas M., Cohen D.A.N., Asai I., Detraux J., Gautam S., Möller H.J., Ndetei D.M., Newcomer J.W., Uwakwe R., Leucht S. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M., Dekker J.M., Wood D., Kahl K.G., Holt R.I.G., Möller H.J. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes in people with severe mental illness position statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur. Psychiatry. 2009;24(6):412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M., Mazereel V., Detraux J., Van Assche K. Prioritizing COVID-19 vaccination for people with severe mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2020;2021:1. doi: 10.1002/wps.20826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Picker L.J., Dias M.C., Benros M.E., Vai B., Branchi I., Benedetti F., Borsini A., Leza J.C., Kärkkäinen H., Männikkö M., Pariante C.M., Güngör E.S., Szczegielniak A., Tamouza R., van der Markt A., Fusar-Poli P., Beezhold J., Leboyer M. Severe mental illness and European COVID-19 vaccination strategies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(5):356–359. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Serres G., Rouleau I., Skowronski D.M., Ouakki M., Lacroix K., Bédard F., Toth E., Landry M., Dupré N. Paresthesia and sensory disturbances associated with 2009 pandemic vaccine receipt: clinical features and risk factors. Vaccine. 2015;33(36):4464–4471. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson F., Stallings C., Origoni A., Vaughan C., Khushalani S., Yolken R. Elevated C-reactive protein and cognitive deficits in individuals with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):456–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford B.N., Yolken R.H., Dickerson F.B., Teague T.K., Irwin M.R., Paulus M.P., Savitz J. Reduced immunity to measles in adults with major depressive disorder. Psychol. Med. 2019;49(2):243. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718000661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris C., Barraclough B. Addressing mental health needs disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1998;173(1):11–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J.F., Miles J., Walters K., King M., Osborn D.P.J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of premature mortality in bipolar affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2015;131(6):417–425. doi: 10.1111/acps.12408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heggelund J., Vancampfort D., Tacchi M.J., Morken G., Scott J. Is there an association between cardiorespiratory fitness and stage of illness in psychotic disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020;141(3):190–205. doi: 10.1111/acps.13119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Gómez A., Andrade-González N., Lahera G., Vieta E. Recommendations for the care of patients with bipolar disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;279:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessing L.V., Ziersen S.C., Andersen P.K., Vinberg M.J.A. Nation-wide population-based longitudinal study mapping physical diseases in patients with bipolar disorder and their siblings. Affect Disord. 2021;282:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon D.S., Kim K., Park S.M. Factors associated with influenza vaccination coverage among the elderly in South Korea: the Fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV) BMJ Open. 2016;6(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012618. e012618. 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner N., Mangge H., Reininghaus E.Z., McIntyre R.S., Bengesser S.A., Birner A., Reininghaus B., Kapfhammer H.P., Wallner-Liebmann S.J. Body fat distribution and associations with metabolic and clinical characteristics in bipolar individuals. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015;265(4):313–319. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0559-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landén M., Larsson H., Lichtenstein P., Westin J., Song J. Respiratory infections during lithium and valproate medication: a within-individual prospective study of 50,000 patients with bipolar disorder. Int. J. Bipolar Disord. 2021;9(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40345-020-00208-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavela S.L., Goldstein B., Etingen B., Miskevics S., Weaver F.M. Factors Associated With H1N1 influenza vaccine receipt in a high-risk population during the 2009-2010 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Top Spinal Cord. Inj. Rehabil. 2012;18(4):306–314. doi: 10.1310/sci1804-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence T., Zubatsky M., Meyer D. The association between mental health diagnoses and influenza vaccine receipt among older primary care patients. Psychol. Health Med. 2020;25(9):1083–1093. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1717557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.W., Yang J.M., Moon S.Y., Yoo I.K., Ha E.K., Kim S.Y., Park U.M., Choi S., Lee S.-.H., Ahn Y.M., Kim J.M., Koh H.Y., Yon D.K. Association between mental illness and COVID-19 susceptibility and clinical outcomes in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(12):1025–1031. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30421-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie D.L., Kobre R.A., Richmand B.J., Aktan Guloksuz S., Leckman J.F. Temporal. Association of certain neuropsychiatric disorders following vaccination of children and adolescents: a pilot case-control study. Front. Psychiatry. 2017;8:3. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maripuu M., Bendix M., Öhlund L., Widerström M., Werneke U. Death Associated With Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in Individuals With Severe Mental Disorders in Sweden During the Early Months of the Outbreak-An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Analysis of a Population-Based Register Study. Front. Psychiatry. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.609579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre R.S., Danilewitz M., Liauw S.S., Kemp D.E., Nguyen H.T., Kahn L.S., Kucyi A., Soczynska J.K., Woldeyohannes H.O., Lachowski A., Kim B., Nathanson J., Alsuwaidan M., Taylor V.H. Bipolar disorder and metabolic syndrome: an international perspective. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;126(3):366–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskovsky E., Gershman K., Clements M.L., Cupps T., Calandra G., Hesley T., Ioli V., Ellis R., Kniskern P., Miller W., Gerety R., West D. Comparative safety and immunogenicity of yeast recombinant hepatitis B vaccines containing S and pre-S2+ S antigens. Vaccine. 1991;9(5):346–350. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90062-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali V., Oyebode F. Poverty, social inequality and mental health. Adv. Psychiatric Treatment. 2004;10(3):216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R.E., Banner J., Jensen S.E. Cardiovascular disease in patients with severe mental illness. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021;18:136–145. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-00463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patanavanich R., Glantz S.A. Smoking is associated with COVID-19 progression: a metaanalysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020;22(9):1653–1656. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather A.A., Pressman S.D., Miller G.E., Cohen S. Temporal Links Between Self-Reported Sleep and Antibody Responses to the Influenza Vaccine. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2021;28:151–158. doi: 10.1007/s12529-020-09879-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queissner R., Pilz R., Dalkner N., Birner A., Bengesser S.A., Platzer M., Fellendorf F.T., Kainzbauer N., Herzog-Eberhard S., Hamm C., Reininghaus B., Zelzer S., Mangge H., Mansur R.B., McIntyre R.S., Kapfhammer H.P., Reininghaus E.Z. The relationship between inflammatory state and quantity of affective episodes in bipolar disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;90:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rødevand L., Steen N.E., Elvsåshagen T., Quintana D.S., Reponen E.J., Mørch R.H., Lunding S.H., Vedal T.S.J., Dieset I., Melle I., Lagerberg T.V., Andreassen O.A. Cardiovascular risk remains high in schizophrenia with modest improvements in bipolar disorder during past decade. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019;139(4):348–360. doi: 10.1111/acps.13008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo R., Ciminale M., Ditommaso S., Siliquini R., Zotti C., Ruggenini A.M. Hepatitis B vaccination in psychiatric patients. Lancet North Am. Ed. 1994;343(8893):356. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminog O.O., Goldacre M.J. Risk of pneumonia and pneumococcal disease in people with severe mental illness: english record linkage studies. Thorax. 2013;68(2):171–176. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinn A.K., Viron M. Perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic and individuals with serious mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3) doi: 10.4088/JCP.20com13412. 20com13412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soresina A., Moratto D., Chiarini M., Paolillo C., Baresi G., Focà E., Bezzi M., Baronio B., Giacomelli M., Badolato R. Two X-linked agammaglobulinemia patients develop pneumonia as COVID-19 manifestation but recover. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2020;31(5):565–569. doi: 10.1111/pai.13263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefana A., Youngstrom E.A., Chen J., Hinshaw S., Maxwell V., Michalak E., Vieta E. The COVID-19 pandemic is a crisis and opportunity for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(6):641–643. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taquet M., Luciano S., Geddes J.R., Harrison P.J. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):130–140. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D., Correll C.U., Galling B., Probst M., De Hert M., Ward P.B., Rosenbaum S., Gaughran F., Lally J., Stubbs B. Diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and large scale meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):166–174. doi: 10.1002/wps.20309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort D., Stubbs B., Mitchell A.J., De Hert M., Wampers M., Ward P.B., Rosenbaum S., Correll C.U. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):339–347. doi: 10.1002/wps.20252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardavas C.I., Nikitara K. COVID-19 and smoking: a systematic review of the evidence. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020;18:20. doi: 10.18332/tid/119324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Jiang M., Chen X., Montaner L.J. Cytokine storm and leukocyte changes in mild versus severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: review of 3939 COVID-19 patients in China and emerging pathogenesis and therapy concepts. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020;108(1):17–41. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3COVR0520-272R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Xu R., Volkow N.D. Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):124–130. doi: 10.1002/wps.20806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman D., Iosue M., Wuestefeld A., Carli V. Adaptation of evidence-based suicide prevention strategies during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):294–306. doi: 10.1002/wps.20801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata A.S., Rizzo L.B., Cerqueira R.O., Scott J., Cordeiro Q., McIntyre R.S., Mansur R.B., Brietzke E. Differential impact of obesity on CD69 expression in individuals with bipolar disorder and healthy controls. Mol. Neuropsychiatry. 2018;3(4):192–196. doi: 10.1159/000486396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H., Chen J.H., Xu Y.F. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e21. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]