Abstract

Objectives:

Normal and chronic wound healing is a global challenge. Electrotherapy has emerged as a novel and efficient technique for treating such wounds in recent decades. Hydrogel applied to the wound to uniformly distribute the electric current is an important component in wound healing electrotherapy. This study reports the development and wound healing efficacy testing of vitamin D entrapped polyaniline (PANI)-chitosan composite hydrogel for electrotherapy.

Materials and Methods:

To determine the morphological and physicochemical properties, techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM); differential scanning calorimetry; X-ray diffraction; fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy were used. Moreover, pH, conductance, viscosity, and porosity were measured to optimize and characterize the vitamin D entrapped PANI-chitosan composite hydrogel. The biodegradation was studied using lysozyme, whereas the water uptake ability was studied using phosphate buffer. Ethanolic phosphate buffer was used to perform the vitamin D entrapment and release study. Cell adhesion, proliferation, and electrical stimulation experiments were conducted by seeding dental pulp stem cells (DPSC) into the scaffolds and performing (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay; SEM images were taken to corroborated the proliferation results. The wound healing efficacy of electrotherapy and the developed hydrogel were studied on excision wound healing model in rats, and the scarfree wound healing was further validated by histopathology analysis.

Results:

The composition of the developed hydrogel was optimized to include 1% w/v PANI and 2% w/v of chitosan composite. This hydrogel showed 1455 μA conduction, 98.97% entrapment efficiency and 99.12% release of vitamin D in 48 hrs. The optimized hydrogel formulation showed neutral pH of 6.96 and had 2198 CP viscosity at 26°C. The hydrogel showed 652.4% swelling index and 100% degradation in 4 weeks. The in vitro cell culture studies performed on hydrogel scaffolds using DPSC and electric stimulation strongly suggested that electrical stimulation enhances the cell proliferation in a three-dimensional (3D) scaffold environment. The in vivo excision wound healing studies also supported the in vitro results suggesting that electrical stimulation of the wound in the presence of the conducting hydrogel and growth factors like vitamin D heals the wound much faster (within 12 days) compared to non-treated control wounds (requires 21 days for complete healing).

Conclusion:

The results strongly suggested that the developed PANI-chitosan composite conducting hydrogel acts effectively as an electric current carrier to distribute the current uniformly across the wound surface. It also acted as a drug delivery vehicle for delivering vitamin D to the wound. The hydrogel provided a moist environment, a 3D matrix for free migration of the cells, and antimicrobial activity due to chitosan, all of which contributed to the electrotherapy’s faster wound healing mechanism, confirmed through the in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Keywords: Polyaniline, chitosan, composite hydrogel, wound healing, electrical stimulation, vitamin D

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), injuries are becoming a more widespread public health issue. It is one of the leading causes of death across the globe annually. According to a WHO survey, about 5.7 million deaths are reported annually due to injuries, accounting for 9% of the total global annual deaths. These deaths represent a very small portion of the injured patients. Millions of people suffer from injuries that require hospitalization, emergency treatments, and consultation of a general practitioner or home remedies.1 An injury is caused by a wound, which is defined as the disruption of the dermis layer and cellular continuity due to an external impact on the skin. Generally, there are five kinds of wounds: Abrasion, puncture, burn, avulsion and laceration. The normal wound healing is slow, and it takes a minimum of 21 days to complete the four phases of wound healing, including hemostasis, inflammatory/defensive phase, proliferative phase, and maturation/remodeling phase.2

Chitosan is an N-de-acetylated derivative of chitin. It is the most abundant biopolymer found in the exoskeleton of crustaceans, mollusks, and insects.3 Chitosan is non-irritant, biodegradable, and biocompatible, and it exhibits high mechanical strength, good film-forming properties, adequate adhesionnon.4,5 Chitosan based hydrogel can be made using various crosslinking agents like genipin, glutaraldehyde, and sodium tripolyphosphate.6 Hydrogels are three-dimensional (3D) swollen structures that contain more than 90% of water. They can swell and retain the volume of the absorbed aqueous medium in their 3D swollen network when placed in an aqueous medium.7 Conducting polymer hydrogels are gels composed of a conducting polymer and a supporting polymer, and they are swollen with water or electrolyte solution. The most widely used conducting polymer are polyaniline (PANI), poly-pyrrole, or poly(3,4-ethylene-dioxythiophene), representing the conducting moiety, while crosslinked water-soluble polymers make up the other part of hydrogel.8

PANI is the most widely used conducting polymer with various applications in molecular sensors, protection of metals from corrosion, gas separating membranes, and rechargeable batteries.9,10,11 PANI exhibits the desired conductivity range; it is easy to synthesize, requires low operational voltage, offers thermal and chemical stability, and is a pH-responsive polymer with different chemical forms, based on acidic/ basic treatment.12,13 Despite these advantages, PANI has some drawbacks, including poor solubility in common organic solvents, poor infusibility, and poor mechanical properties.14,15 Various attempts have been made to circumvent these drawbacks, including doping PANI using specific doping techniques like additives or forming a composite of PANI with another polymer matrix.16,17 The PANI-polymer matrix composite enhances its solubility, mechanical properties, and PANI supplies the conducting properties to the PANI/polymer composite making it stimuli-responsive (pH and external electrical stimuli). Such PANI/polymer matrix is widely employed in sustained drug delivery if the polymer matrix exhibits properties of hydrogel. Its water uptake ability allows the entrapment of drugs or actives inside a 3D matrix and releases them in a controlled manner, making it an advanced candidate for biomedical applications.18

Recent studies have reported on the synthesis of chitosan blends with PANI or its derivatives19,20,21 and using chitosan as a steric stabilizer for stimuli-responsive PANI colloids. In this study, chitosan-PANI composite hydrogel with good mechanical properties and electrical conductivity was developed.22,23 The PANI was initially synthesized using oxidative polymerization reaction followed by formulating chitosan-PANI hydrogel with vitamin D (as a growth factor) in a controlled 3D matrix. PANI was distributed uniformly throughout the chitosan network in these composite hydrogels, and the concentration of the PANI was optimized by considering the conduction requirement for wound healing applications. Chitosan was selected for its biodegradable, hemostatic, antimicrobial, film-forming properties and its structure. Chitosan enhances the conductivity of PANI due to the presence of hydrogen bonds between hydrogelthe hydrogel network and PANI. The formulated hydrogel was lyophilized to get scaffolds of chitosan-PANI to highlight the significance of vitamin-D-loaded matrix in wound healing and for ease of cell line studieshydrogel. These composites’ preliminary application in in vivo wound healing was further demonstrated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Chitosan (cell culture tested-Low molecular weight grade 50,000-190,000, degree of deacetylation 90%) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich, United States. Ammonium persulfate and aniline were purchased from Loba Chemicals, India. Alfa Aesar in India provided the vitamin D. All other chemicals utilized were of the highest purity and analytical grade.

Synthesis of polyaniline

PANI was synthesized using the method reported by, Marcasuzaa et al.24 In a nutshell, 5 mL of aniline was mixed with 100 mL 1M HCl. A 100 mL of 1 M ammonium persulfate solution was added into the mixture as a polymerization initiator. The solution was stirred for 24 hours at 1200 rpm on a magnetic stirrer until a dark green precipitate was formed. The precipitate was washed with distilled water three times to remove free aniline monomers before being recrystallized with methanol. The precipitate was then dried for 24 hours to get fibrous powder.

Preparation of conducting polymer-based hydrogel (conducting hydrogel)

Chitosan was slowly added to 1% acetic acid solution, under constant stirring, using a homogenizer. Vitamin D (dissolved in 6:4 v/v water:ethanol ratio) and PANI were added after the chitosan is dissolved completely, and the mixture was continuously stirred to uniformly distribute the PANI.25 Vitamin D was used as a growth factor (drug) because it has previously been reported to improve wound healing.26 Furthermore, a sodium TPP solution was added dropwise and stirred for 30 minutes to get a homogenized gel. The hydrogel was used for characterization and animal study. Hydrogel was lyophilized to form scaffolds for cell line studies.

Experimental section

Physicochemical characterization

The appearance and color of the hydrogel was determined by visual observation. A digital pH meter (ELICO LI-120, India) was utilized to measure the pH of the optimized batch and the blank hydrogel.

Conductivity

The conductivity of the blank and optimized batch of hydrogel was determined using a two probe conductivity meter (Labman- EQ-650, India).27

Viscosity

The viscosity of the conducting hydrogel and the blank hydrogel was verified using Brookfield viscometer (DV PRO-II, USA). The torque and viscosity were recorded at 26°C with a spindle no: 18 fitted on a small sample adapter at different rpm (10-40), and the Newtonian behavior of the hydrogels was predicted.28

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The porosity and morphology of the lyophilized hydrogels were studied using a SEM (FEI Nova Nano SEM 450, India) machine. The samples were first coated using a gold sputter coater (SPI module sputter coater, USA). The samples were then randomly scanned, and photomicrographs were taken at the acceleration voltage of 10 kV.29

Fourier-transform infrared spectrophotometer (FTIR)

The lyophilized blank and the conducting hydrogel powders were characterized by FTIR. The FTIR spectra were recorded using a FTIR (Shimadzu scientific instruments, model no 8400s, Japan) using KBr pellets.30 The spectra were recorded and compared from 600 to 4500 cm-1.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

The DSC study was carried out using (Mettler-Toledo DSC-I, USA) for the lyophilized blank and conductive polymer hydrogels. The samples were heated from 40°C to 300°C at the rate of 10°C/min. For accurate results, an inert atmosphere was maintained throughout the experiment by purging nitrogen gas at the rate of 50-70 mL/min using a crimped aluminum pan.29

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The XRD study was carried out for the blank hydrogel and the conducting hydrogel, using a Rigaku Miniflex-600 instrument from a scanning range of 2θ to 80θ.30

Drug entrapment efficiency

The drug (vitamin D) loaded crosslinked hydrogel (5 g) was added to 50 mL of ethanolic phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 26°C for 2 hours with frequent sonication (at every 20 min) to release all the drug entrapped in the crosslinked matrix. The amount of free drug (vitamin D) was determined by collecting clear supernatant using ultraviolet spectroscopy at 262 nm. The supernatant from the empty hydrogel (without crosslinker) was taken as a blank,31 and the drug entrapments of the crosslinked and normal matrix were compared.

Drug diffusion study

In vitro diffusion studies of the prepared hydrogel were carried out in a Franz-diffusion cell using a 25 mL ethanolic phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with the temperature maintained at 37±1°C. The acceptor compartment of the cell was filled with the 25 mL ethanolic phosphate buffer 7.4 and stirred continuously with a small magnetic bead. The donor compartment was filled with the hydrogel (equivalent to 50 mg of vitamin D). The 100 µL sample was withdrawn at specific time intervals to assess the release of vitamin D from the hydrogel in the donor compartment. The sink condition due to sample withdrawal was maintained by replenishing the receiver compartment with an equal amount of ethanolic phosphate buffer.32

Water uptake ability swelling behavior

Pre-weighed scaffold was immersed in the swelling medium (phosphate buffer pH: 7.4).33,34 Scaffolds were removed using a spatula at various intervals and placed on filter paper to remove excess water and immediately weighed. The procedure was repeated and continued until no weight increase was observed. The swelling percent was calculated using equation (1)

Q = (Ms – Md) / Md x 100 equation (1)

where, Q=is the swelling ratio; Ms=is the mass in the swollen state; Md=is the mass in the dried state.

Biodegradation study

The scaffolds degradation was performed in a phosphate buffer saline solution (phosphate buffered saline, pH: 7.4), containing 800 mg/L of lysozyme, at 37°C in an orbital shaker at 50 rpm for four weeks. The lysozyme solution was replaced with a fresh one after every three days. The samples were analyzed at a predetermined time (1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks, respectively). The samples were removed from the medium, rinsed with distilled water, and dried in an oven at 50°C until a constant mass is reached.35 The degradation degree (Δm) was determined as the weight loss percent with respect to the initial weight of the sample and calculated using equation (2).

Δm (%) = m1 - m2 / m1 ×100 equation (2)

where, Δm is the degree of biodegradation; m1 is the initial weight of the scaffold; m2 is the weight of the scaffolds after the predetermined rate.

Cell proliferation studies

The effect of electric current (1 mA supplied using BioRad power supply) on the cell survival and proliferation was studied using stem cells isolated from dental pulp stem cell (DPSC). The DPSC were selected for this study as they easily undergo differentiation under the influence of growth factors like vitamin D to give the multiple differentiated cells required for better angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Angiogenesis and neurogenesis are the rate-limiting stages in the wound healing process. As a result, using DPSC can effectively address this issue in wound healing leading to faster healing. The in vitro cell proliferation studies were conducted to prove that the DPSCs can significantly survive in the developed conducting hydrogel. The cell proliferation and viability of the DPSCs seeded in the conducting scaffold treated and not treated with a small electric current (1 mA) were assessed using (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) (MTT) assay.

The cells were sub-cultured in 20% fetal bovine serum- Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium-F12 with 1% penicillin-streptomycin medium to determine the proliferation of DPSCs. When the cells were 90% confluent, 1×104 cells / mL were seeded into two 24-well culture plates separately containing blank and conducting hydrogel scaffolds (5 mm height and 4 mm diameter cylindrical scaffold). The plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator.

The MTT assay was performed (N=6 samples each) every 5 days for the scaffolds, with and without electrical stimulation for a total of 15 days, with absorbance readings recorded at 570 nm.36 The population doubling times (PDT) was then calculated using equation (3).

PDT = T log2 / log FCC – log ICC equation (3)

where, ICC is the initial cell count, FCC is the final cell count, and T is the incubation time (in hours).

In vivo wound healing study

Excision wound healing using Wistar albino rats model was carried out after CPCSEA Clearance (approval no: DYPIPSR/IAEC/Nov./18-19/P-09 Date 25/11/2019). The animals were placed into four groups (n=6) in this study; group 1 was treated as a control group (not treated with anything), group 2 as a standard group (treated with cipladine), group 3 as a blank hydrogel, and group 4 as a CP-based hydrogel. In all the groups, a full-thickness excision wound was created on the back of the Wister rats. Wound healing was monitored by measuring the wound area. Equation (4) was employed to calculate the wound area and the % wound contraction.

% Wound Contraction = (A0 – At) / A0 x 100 equation (4)

where, A0 and At are the initial wound area and wound area after a time interval t, respectively.

Histopathology

Following a 15-day in vivo wound healing study, a patch of 1 cm×1 cm skin sample from the healed wound was excised for histopathological studies. Healed skin of the rat was fixed in neutral buffered formalin, and a standard histopathology procedure was conducted. The tissues were trimmed longitudinally and routinely processed in ascending grades of alcohol to dehydrate them, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax. Paraffin wax embedded tissue blocks were sectioned at 3 µm thickness with the Rotary Microtome. All the slides of the skin were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain. The prepared slides were examined under a microscope to note histopathological lesions like angiogenesis, inflammatory cell (neutrophilic/lymphocytic) infiltration, edema and fibroblast, necrosis, and scar tissue formation. The severity of the observed lesions was recorded as minimal (<1%), mild (1-25%), moderate (26-50%), moderately severe (51-75%), severe (76-100%), respectively, and the distribution was recorded as colored arrows.36

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Appearance

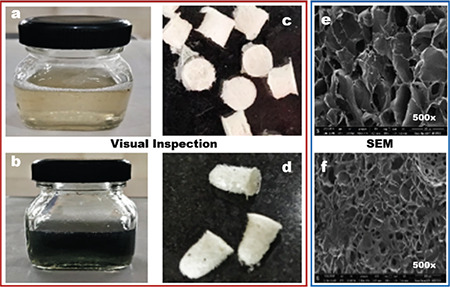

The color, odor, and appearance of the prepared formulation were visually inspected. The blank hydrogel appeared to be a slight yellowish translucent gel (Figure 1a), and the conducting hydrogel appeared as a dark green colored translucent gel (Figure 1b). The blank scaffolds were white, porous 3D matrix (Figure 1c), and the conductive scaffolds were slightly greenish 3D structures (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Appearance and morphology of the gel and scaffolds: a) and b) blank and conducting hydrogel respectively; c) and d) blank and conducting hydrogel scaffolds respectively; e) and f) SEM images of blank and conducting hydrogel scaffolds respectively

SEM: Scanning electron microscopy

pH Measurement

The pH of the conducting hydrogel was 6.94, which is neutral. It was compared to the pH of the blank hydrogel, which was found to be 6.4. In the in vivo animal studies, this increased pH permitted the direct application of formulation on the wound and did not cause any redness or irritation at the wound site.

Conductivity

The conducting hydrogel showed better conductivity of 1455 µA when compared to the conductivity of the blank hydrogel (0.098 µA). The previously reported results for poly-pyrrole-based conducting hydrogel with the same concentration was 1849 µA, which is quite close to our findings.37,38

Viscosity

The viscosity of the blank hydrogel and the conducting hydrogel was determined using a Brookfield viscometer. It was observed that hydrogels showed a shear-thinning behavior, as the viscosity decreased with increase stress from 3.198 to 2.198 CP for the blank hydrogel and from 3.280 to 2.208 for the CP-based hydrogel. Similar results were reported by Mawad et al.39 for single component CP-based hydrogel using an in-situ approach.

SEM analysis

The SEM images of non-crosslinked (blank) and crosslinked (conducting) hydrogels are shown in Figure 1e, f, respectively. When observed at 500×, the obtained scaffolds revealed irregular pore sizes ranging from 100-230 µm. The crosslinked batch was more porous than the batch without crosslinking, which might be due to the higher interaction with TPP.

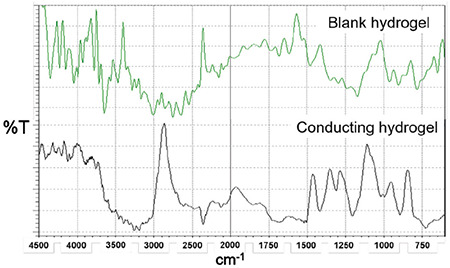

IR spectra spectral analysis

Figure 2 shows the IR spectra of chitosan and the conducting hydrogel. The observed frequencies for the blank hydrogel (Figure 2a) OH stretching, N-H bending, CH stretching of CH3 and CH2 groups, and NH-C=O amide bending were observed at 3.628, 3.379, 3.000,, and 1.705 cm-1, respectively. The obtained values are consistent with the previously reported results by Kodama et al.40 Hydrogel the frequencies for C-H stretching, O-H stretching, C-O stretching, C=O stretching, and C-N stretching in the IR spectra of the conducting hydrogel scaffold (Figure 2) are depicted at 2.864, 3.495, 1.022, 1.649, and 1.270 cm-1, respectively. The obtained values closely matched the previously reported results by Oka et al.41

Figure 2.

IR spectra of blank hydrogel and conducting hydrogel

IR: Infrared spectrophotometer

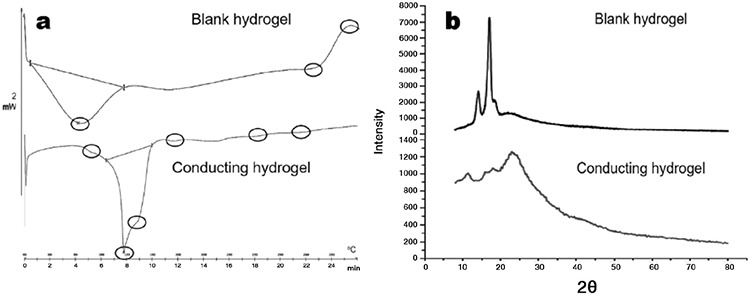

DSC thermogram analysis

DSC spectra are illustrated in Figure 3a. The DSC spectra of the blank hydrogel revealed a sharp endothermic peak at 82.24°C, which was owing to water loss, and a broad endothermic peak at 268°C followed by a broad exothermic peak at 288°C, which indicates chitosan decomposition. These values are consistent with previously reported values by Martins et al.20 The conducting hydrogel’s DSC thermogram hydrogelshowed a peak at 90°C, which was linked to moisture loss. The sharp endothermic peak at 117.53°C indicated the peak degradation of vitamin D, a broad endothermic peak at 133.69°C followed by a broad exothermic peak at 144.69°C indicated PANI decomposition. The endothermic peak at 270°C followed by the exothermic peak at 292°C confirmed the chitosan degradation, and the obtained results were quite similar to those previously reported by Thanpitcha et al.42

Figure 3.

a) DSC spectra of blank and conducting hydrogel; b) XRD spectra of blank and conducting hydrogel

DSC: Differential scanning calorimetry, XRD: X-ray diffraction

XRD spectral analysis

The blank hydrogel and conducting hydrogel’s diffractogram hydrogel is shown in Figure 3b. Broad characteristic peaks of the blank hydrogel were observed at 13 and 17 degrees 2θ in crystallographic planes, suggesting amorphous natured chitosan. The obtained values were consistent with those of Badhe et al.43 The conducting hydrogel is comprised of a dense network structure of interpenetrating polymer chains crosslinked to each other by TPP. Thus, the vitamin-D-loaded conducting hydrogel’s diffractogram sharp peaks at 13θ, and 17θ represent chitosan, 25θ represents vitamin D, and the broad peak at 43θ represents the amorphous nature of PANI. The obtained results are comparable to previously reported results by Sultana et al.44

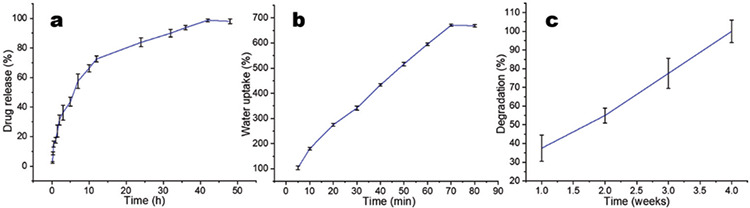

Drug entrapment efficiency/drug diffusion study

The entrapment efficiency for the conducting hydrogel was found to be 98.97%. The reported standard drug entrapment efficiency for chitosan scaffolds was 97-100%. Through the Franz diffusion cell using dialysis membrane, the in vitro release profile of vitamin D was found to be 99.12% in 48 hours, as depicted in Figure 4a. After 52 hours, the release of vitamin D was reported to be 99% for poly-pyrrole-based hydrogel. Crosslinking can be predicted to increase the release time.45

Figure 4.

a) Drug release (of vitamin D); b) water uptake; and c) degradation studies of conducting hydrogel

Water uptake ability swelling behavior

The medium water uptake ability, which was about 652.4%, was assessed by determining the swelling index of scaffolds in the phosphate buffer at 37°C. Figure 4b revealed that after 70 minutes, there was no significant increase in the water uptake ability of the scaffolds. Previous reports by Mawad et al.,39 suggested a 787.69% water uptake ability for poly-pyrrole-based scaffolds, which aligns closely with previously reported results.

Biodegradation study

The research was carried out until the scaffolds were completely removed. The results (Figure 4c) revealed that the scaffolds showed gradual weight loss until the fourth week after which they were completely degraded. Biodegradation was shown to be 91-94% after the seventh week in some previous reports hydrogel. The conducting hydrogel scaffold degraded in 4 weeks, which might be attributed to the chitosan molecular weight.44

Cell proliferation study

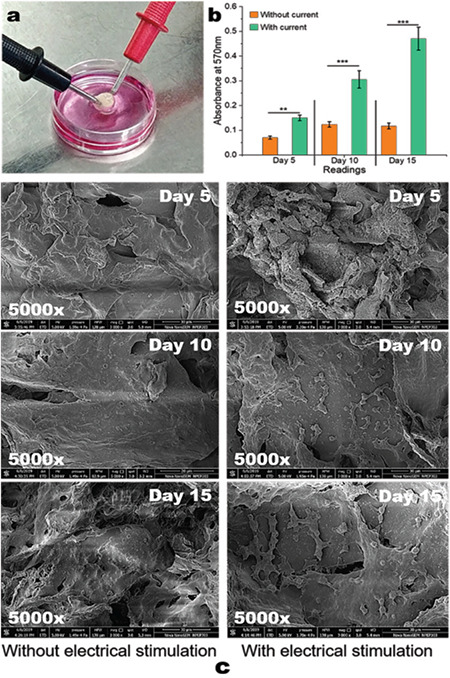

DPSC isolated from dental pulp were employed for the cell proliferation studies. The scaffolds were electrically stimulated for 15 days during these studies (Figure 5a). It was observed that electrical stimulation helps in the faster proliferation of the cells compared to non-electrical stimulated scaffolds (Figure 5b). Some previously reported studies have shown an over 21 days stem cells proliferation when seeded in scaffolds (significance **p≤0.01 and ***p≤0.005), respectively.46,47 Figure 5c shows the SEM images demonstrating improved proliferation with electrical stimulation; it was concluded that electric current supports the cell proliferation.

Figure 5.

a) Scaffolds electrical stimulation; b) graph of cell proliferation studies performed using MTT assay (**p≤0.01 and ***p≤0.005); c) SEM images of cells seeded scaffolds with and without electrical stimulation

MTT: (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide), SEM: Scanning electron microscopy

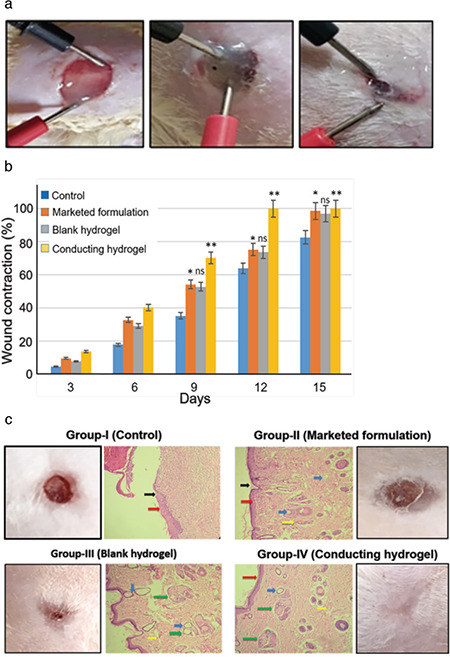

In vivo wound healing study

Figure 6a shows the results of wound healing animal studies using electrical stimulation. The % wound contraction results were statistically analyzed by One-Way ANOVA (n=6), **p<0.01, *p<0.05. Compared to the control and blank hydrogels, wound healing in the animals treated with conducting hydrogel was found to be significantly faster hydrogel (Figure 6b). Thus, the study backs up the observations that electrical stimulation of the wound with the conducting hydrogel speeds up wound healing (within 12 days) compared to the control hydrogel (which took 21 days to heal completely).48

Figure 6.

a) % wound contraction graph (**p≤0.01 and *p≤0.05); b) application of conducting hydrogel and electrical current at different time intervals (every 3 days); c) histopathology results (black arrows indicates scar tissue formation, red arrows indicates healing wound/initiation of re- epithelization, blue arrows indicates edema and fibroblasts and yellow arrow indicates necrosis, green arrows in group III and IV indicated initiation of collagen regrowth at wound site)

Histopathology

Microscopic examination of the skin revealed mild epidermal hyperplasia with fibrosis in animals belonging to the control group; whereas other groups showed normal epidermis and dermis. The results are shown in Figure 6c. Collagen synthesis, fibroblast migration, and epithelization are seen in group III (blank hydrogel) and group IV (conducting hydrogel), implying the generation of healthy and flexible skin tissue without scar tissue. On the other hand, group II (marketed formulation) only showed epithelization, fibroblast migration, and necrosis, indicating scar tissue formation. Thus, it can be concluded that both the blank and the conducting hydrogels helped in scar-free wound healing, and the electrical stimulation of the conducting hydrogel helped in faster wound healing without scar tissue formation. The same phenomenon is observed in the healed skin images of the animals in Figure 6c.

DISCUSSION

Injuries and wounds are among the most prevalent health concerns we face daily. Generally, small injuries like abrasion or cuts heal naturally without infection and with little care. Emergency medical help is required for large wounds, like laceration, avulsion, incision, or amputation. Many of these wounds heal at a slower rate due to infections and patient health/age conditions. Non-responding or chronic injuries are a distinct class of injuries that is mainly observed in burns, diabetic and obese patients. These types of injuries pose a potential burden on our healthcare system and patients’ finances. There are various treatments available for these types of wounds, including hyperbaric oxygen therapy, plastic surgeries, grafts, negative pressure therapy, and electrotherapy. These techniques have their advantages and disadvantages, but electrotherapy has proven to be more useful and cost-effective.

Electrotherapy treatment applies a small electric current (200-800 µA) to help the wound heal faster by mimicking the current of an injury. However, an equally effective hydrogel that can distribute the applied electric current throughout the wound is required to get the maximum benefit from the therapy.49 This research work focused on developing optimized conducting hydrogel, which can uniformly distribute electric current throughout the wound. In addition to the electric current distribution, the developed hydrogel also serves as a drug delivery vehicle delivering vitamin D as a growth factor. Furthermore, the PANI-chitosan hydrogel base also acts as an antimicrobial wound closure to protect the wound from secondary infection. The hydrogel’s highly biocompatible and biodegradable nature provides a moist 3D environment to the wound allowing the cells (fibroblast, keratinocyte) to migrate in a 3D environment to heal the wound faster. The daily electrical stimulation helps the wound heal with normal healthy skin without scar tissue by enhancing the migration of the cells and providing a moist environment with vitamin D (supporting angiogenesis and neurogenesis).

Though the study reported here showed very promising results with the developed hydrogel, there are certain limitations.

CONCLUSION

The study was performed using a 1 mA current, which is slightly higher than the actual current of an injury; optimizing the current will produce better results. This study establishes the biodegradation of the hydrogel but the non-degradable PANI (though in small amounts) needs to be addressed. Understanding these limitations will allow for further modifications of the hydrogel with novel biodegradable and effective conducting materials. Further studies with new drug entity immobilization in hydrogel for the same application are also planned.

Acknowledgments

Authors are very thankful to Dr. D. Y. Patil Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research for providing the lab space and animal house to carry out the research work.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors. The authors are solely responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Caló E, Khutoryanskiy VV. Biomedical applications of hydrogels: a review of patents and commercial products. Eur Polym J. 2015;65:252–267. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swarbrick J. Encyclopedia of pharmaceutics. (4th ed) Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoare TR, Kohane DS. Hydrogels in drug delivery: progress and challenges. Polymer. 2008;49:1993–2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De France KJ, Xu F, Hoare T. Structured macroporous hydrogels: progress, challenges, and opportunities. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larrañeta E, Stewart S, Ervine M, Al-Kasasbeh R, Donnelly RF. Hydrogels for hydrophobic drug delivery. classification, synthesis and applications. J Funct Biomater. 2018;9:13. doi: 10.3390/jfb9010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson J, Lee V. Controlled drug delivery, fundamentals and applications. 2nd ed. New York; Informa Healthcare USA Inc. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra S, Rani P, Sen G, Dey KP. Preparation, properties and application of hydrogels: a Review. Singapore: Springer. 2018:145–173. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiu Y, Park K. Environment-sensitive hydrogels for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53:321–339. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta P, Vermani K, Garg S. Hydrogels: from controlled release to pH-responsive drug delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2002;7:569–579. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(02)02255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamath KR, Par K. Biodegradable hydrogels in drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1993;11:59–84. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chien Y. Novel drug delivery systems. 2nd ed. New York: Informa Healthcare USA Inc. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhattarai N, Gunn J, Zhang M. Chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled, localized drug delivery. J Adv Drug Deliv. 2010;62:83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carterall William A. Molecular mechanisms of gating and drug block of sodium channels. Sodium Channels and Neuronal Hyperexcitability. Novartis Foundation Symposia. 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson SM, Smith C. Polysaccharide: chitin and chitosan: chemistry and technology of their use as structural materials. In: Kaplan DL, ed. Biopolymers from renewable resources. New York: Springer-Verlag. 1998:96–118. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutta PK, Ravikumar MNV, Dutta J. Chitin and chitosan for versatile applications. JMS Polym Rev. 2002;42:307–354. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma R, Gupta PP, Satapathy T, Roy A. A review of wound healing activity on different wound models. J Appl Pharm Res. 2019;7:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayakumar R, Prabaharan M, Sudheesh Kumar PT, Nair SV, Tamura H. Biomaterials based on chitin and chitosan in wound dressing applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2011;29:322–337. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger J, Reist M, Mayer JM, Felt O, Peppas NA, Gurny R. Structure and interactions in covalently and ionically crosslinked chitosan hydrogels for biomedical applications. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2004;57:19–34. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(03)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran PA, Zhang L, Webster TJ. Carbon nanofibers and carbon nanotubes in regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:1097–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martins AM, Eng G, Caridade SG, Mano JF, Reis RL, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Electrically conductive chitosan/carbon scaffolds for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:635–643. doi: 10.1021/bm401679q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao M. Electrical fields in wound healing-An overriding signal that directs cell migration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wedmore I, McManus JG, Pusateri AE, Holcomb JB. A special report on the chitosan-based hemostatic dressing: experience in current combat operations. J Trauma. 2006;60:655–658. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199392.91772.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anithaa A, Sowmyaa S, Sudheesh KPT, Deepthi S, Chennazhi KP. Chitin and chitosan in selected biomedical applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2014;39:1644–1667. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcasuzaa P, Reynaud S, Ehrenfeld F, Khoukh A, Desbrieres J. Chitosan-graft-polyaniline-based hydrogels: elaboration and properties. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:1684–1691. doi: 10.1021/bm100379z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diarrassouba F, Remondetto G, Liang L, Garrait G, Beyssac E, Subirade M. Effects of gastrointestinal pH conditions on the stability of the β-lactoglobulin/vitamin D3 complex and on the solubility of vitamin D3. Food Res Int. 2013;52:515–521. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkiewicz CJ, Guadagnin FA, Skare TL, do Nascimento MM, Servin SC, de Souza GD. Vitamin D and skin repair: a prospective, double-blind and placebo controlled study in the healing of leg ulcers. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2012;39:401–407. doi: 10.1590/s0100-69912012000500011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahini A, Yazdimamaghani M, Walker KJ, Eastman MA, Hatami-Marbini H, Smith BJ, Ricci JL, Madihally SV, Vashaee D, Tayebi L. 3D conductive nanocomposite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Int J Nanomedicine. 2014;9:167–181. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S54668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lira LM, de Torresi SI. Conducting polymer–hydrogel composites for electrochemical release devices: synthesis and characterization of semi-interpenetrating polyaniline–polyacrylamide networks. Electrochem Commun. 2005;7:717–723. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green RA, Baek S, Poole-Warren LA, Martens PJ. Conducting polymer-hydrogels for medical electrode applications. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2010;11:014107. doi: 10.1088/1468-6996/11/1/014107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barthus RC, Lira LM, Torresi SI. Conducting polymer-hydrogel blends for electrochemically controlled drug release devices. J Brazil Chem Soc. 2008;19:630–636. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stejskal J, Bober P. Conducting polymer colloids, hydrogels, and cryogels: common start to various destinations. Colloid Polym Sci. 2018;296:989–994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardy JG, Lee JY, Schmidt CE. Biomimetic conducting polymer-based tissue scaffolds. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:847–854. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao F, Shi Y, Pan L, Yu G. Multifunctional nanostructured conductive polymer gels: synthesis, properties, and applications. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50:1734–1743. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JY. Electrically conducting polymer-based nanofibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Polym Rev. 2013;53:443–459. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J, Choe G, Yang S, Jo H, Lee JY. Polypyrrole-incorporated conductive hyaluronic acid hydrogels. Biomater Res. 2016;20:31. doi: 10.1186/s40824-016-0078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salehi M, Ehterami A, Farzamfar S, Vaez A, Ebrahimi-Barough S. Accelerating healing of excisional wound with alginate hydrogel containing naringenin in rat model. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2021;11:142–153. doi: 10.1007/s13346-020-00731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramadan A, Elsaidy M, Zyada R. Effect of low-intensity direct current on the healing of chronic wounds: a literature review. J Wound Care. 2008;17:292–296. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2008.17.7.30520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunckler J, de Mel A. A current affair: electrotherapy in wound healing. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:179–194. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S127207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mawad D, Stewart E, Officer DL, Romeo T, Wagner P, Wagner K, Wallace GG. Conducting polymer hydrogels: a single component conducting polymer hydrogel as a scaffold for tissue engineering. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:2691. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kodama H, Inoue T, Watanabe R, Yasuoka H, Kawakami Y, Ogawa S, Ikeda Y, Mikoshiba K, Kuwana M. Cardiomyogenic potential of mesenchymal progenitors derived from human circulating CD14+ monocytes. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:676–686. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oka T, Maillet M, Watt AJ, Schwartz RJ, Aronow BJ, Duncan SA, Molkentin JD. Cardiac-specific deletion of Gata4 reveals its requirement for hypertrophy, compensation, and myocyte viability. Circ Res. 2006;98:837–845. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000215985.18538.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thanpitcha T, Sirivat A, Jamieson AM, Rujiravanit R. Preparation and characterization of polyaniline/chitosan blend film. Carbohydr Polym. 2006;64:560–568. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Badhe RV, Bijukumar D, Chejara DR, Mabrouk M, Choonara YE, Kumar P, du Toit LC, Kondiah PPD, Pillay V. A composite chitosan-gelatin bi-layered, biomimetic macroporous scaffold for blood vessel tissue engineering. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;157:1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.09.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sultana S, Ahmad N, Faisal SM, Owais M, Sabir S. Synthesis, characterisation and potential applications of polyaniline/chitosan-Ag-nano-biocomposite. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017;11:835–842. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iida ASL, Luz KN, Barros-Alexandrino TT, Fávaro-Trindade CS, de Pinho SC, Assis OBG, Martelli-Tosi M. Investigation of TPP-Chitosomes particles structure and stability as encapsulating agent of cholecalciferol. Polímeros. 2019;29:e2019049. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bakopoulou A, Georgopoulou A, Grivas I, Bekiari C, Prymak O, Loza K, Epple M, Papadopoulos GC, Koidis P, Chatzinikolaidou M. Dental pulp stem cells in chitosan/gelatin scaffolds for enhanced orofacial bone regeneration. Dent Mater. 2019;35:310–327. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2018.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moutsatsou P, Coopman K, Georgiadou S. Biocompatibility assessment of conducting pani/chitosan nanofibers for wound healing applications. Polymers (Basel). 2017;9:687. doi: 10.3390/polym9120687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen X, Zhang M, Wang X, Chen Y, Yan Y, Zhang L, Zhang L. Peptidemodified chitosan hydrogels promote skin wound healing by enhancing wound angiogenesis and inhibiting inflammation. Am J Transl Res. 2017;9:2352–2362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Badhe RV, Nipate SS. Low-intensity current (LIC) stimulation of subcutaneous adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs) - A missing link in the course of LIC based wound healing. Med Hypotheses. 2019;125:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]