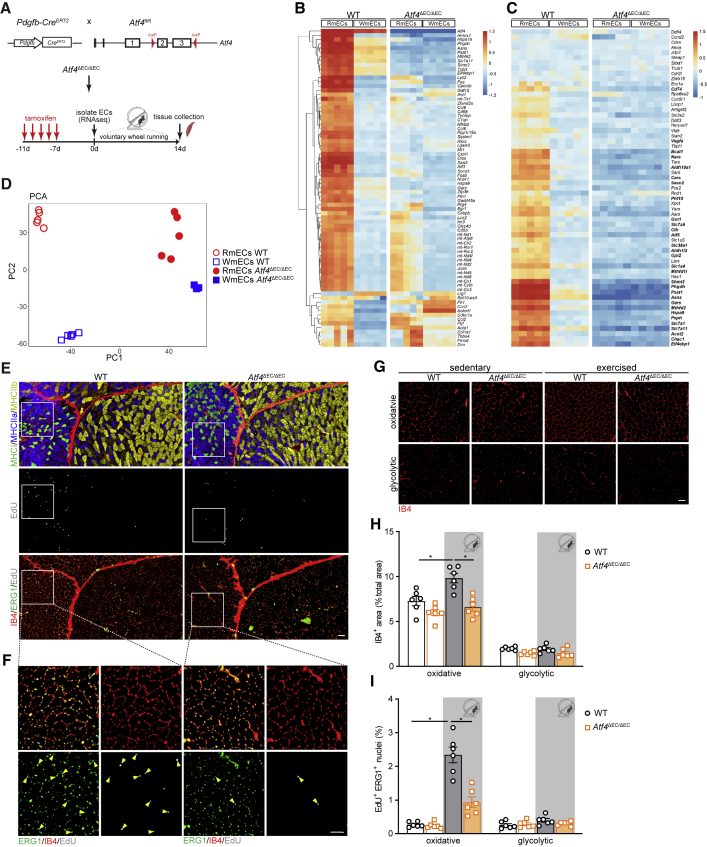

Figure 6.

Deletion of Atf4 in ECs impairs exercise-induced EC proliferation and vascular expansion

(A) Scheme showing the generation of Pdgfb-Cre × Atf4Loxp/Loxp (Atf4ΔEC) mice and experimental plan.

(B) Left: heatmap of the top 75 most highly variable genes in WT RmECs versus WT WmECs. Right: relative expression in Atf4ΔEC/ΔEC RmECs versus Atf4ΔEC/ΔEC WmECs.

(C) Left: heatmap showing relative expression of ATF4-dependent anabolic gene set in WT RmECs versus WT WmECs. Right: relative expression in Atf4ΔEC/ΔEC RmECs versus Atf4ΔEC/ΔEC WmECs. Bold gene names refer to DEGs between WT RmECs and WT WmECs (log fold change > 1 and adjusted p value < 0.05).

(D) PCA showing sample distances between RmECs and WmECs (WT and Atf4ΔEC/ΔEC).

(E and F) Representative fluorescence images of serial sections of QUAD from WT and Atf4ΔEC/ΔEC mice stained for type I (MHCI, green), type IIa (MHCIIa, blue), and type IIb (MHCIIb,yellow) fibers (first section) and EdU incorporation (gray) co-stained with IB4 (red) and ERG (green) (second section) after 14 days of exercise (E). Scale bar, 100 μm. Magnification of white box is shown in (F); arrows indicate EdU+ERG+ ECs. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(G) Representative fluorescence images of IB4 vascular staining in glycolytic and oxidative areas of QUAD from WT and Atf4ΔEC/ΔEC mice in sedentary and exercised conditions. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(H and I) Quantification of IB4+ area (% of total area) (H) and the percentage of EdU+ERG+ ECs (I) in oxidative versus glycolytic areas in QUAD of WT versus Atf4ΔEC/ΔEC mice in sedentary and after exercise (n = 6). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (∗p < 0.05; n.s., not significant). Each dot represents a single mouse.

Bar graphs represent mean ± SEM. See also Figure S6.