Abstract

Background and Objectives

During past years, gamification has become a major trend in technology, and promising results of its effectiveness have been reported. However, prior research has predominantly focused on examining the effects of gamification among young adults, while other demographic groups such as older adults have received less attention. In this review, we synthesize existing scholarly work on the impact of gamification for older adults.

Research Design and Methods

A systematic search was conducted using 4 academic databases from inception through January 2019. A rigorous selection process was followed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Results

Twelve empirical peer-reviewed studies written in English, focusing on older adults aged ≥55, including a gameful intervention, and assessing subjective or objective outcomes were identified. Eleven of the 12 studies were conducted in the health domain. Randomized controlled study settings were reported in 8 studies. Positively oriented results were reported in 10 of 12 studies on visual attention rehabilitation, diabetes control, increasing positive emotions for patients with subthreshold depression, cognitive training and memory tests, engagement in training program, perceptions of self-efficacy, motivation and positive emotions of social gameplay conditions, increased physical activity and balancing ability, and increased learning performance and autonomy experiences. The results are, however, mostly weak indications of positive effects.

Discussion and Implications

Overall, the studies on gameful interventions for older adults suggest that senior users may benefit from gamification and game-based interventions, especially in the health domain. However, due to methodological shortcomings and limited amount of research available, further work in the area is called for.

Keywords: Information technology, Social media/networks, Analysis—literature review, Games

In recent years, we have witnessed an upsurge in how game-like elements and interactions are being employed in various nongame contexts (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019). Games are known to excel in engaging us to play them, even for long periods of time (Ryan, Rigby, & Przybylski, 2006). Thus, system and service designers are seeking to harness the motivational elements of games and use them to create similar engagement in other contexts. This design approach has often been titled as gamification, and it has been defined as a design approach that seeks to induce similar experiences as games, in the context of other systems and services (Deterding, Dixon, Khaled, & Nacke, 2011; Huotari & Hamari, 2017). The aim of the design approach is to increase motivation and long-term engagement with the behaviors that these systems and services support (Huotari & Hamari, 2017), for example, exercise, healthy diet, environmental behavior, or work productivity (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019).

While accumulated research indicates that gamification can be effective in various contexts and support desired behaviors (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019; Seaborn & Fels, 2015), it is acknowledged that gamification implementations are highly contextual (Deterding, 2015) and generalizing results from one context to another is challenging (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019). For example, demographic factors (Koivisto & Hamari, 2014), as well as the nature of the activity being gamified (Hamari, 2013), have been suggested to potentially affect the outcomes of gamification. In terms of demographics, age is an apparent factor that affects our technology needs, as well as the ways that we use it (Czaja & Lee, 2009). In gamification research, most studies have been conducted with young adults who are considered as the prime target group for gameful interactions. However, focusing on a single user demographic limits the generalizability of research results. Thus, as suggested by Koivisto and Hamari (2019), research with more varied user profiles is called for.

One of the demographic groups that has been given limited attention within the gamification research domain is older adults. Modern society is undergoing a substantial demographic shift due to population aging. According to United Nations population trends (United Nations, 2017), the number of older persons aged 60 or more worldwide was close to 1 billion in 2017 and is expected to double by the year 2050. Furthermore, while the population ages, the elders of the coming years are also leading increasingly healthy lives, consequently have a longer life expectancy, and are also increasingly more educated (Sigelman & Rider, 2014). Thus, older adults represent an increasing growth group of technology users, with their own particular needs and challenges (Hill, Betts, & Gardner, 2015; Vroman, Arthanat, & Lysack, 2015). This gives rise to new opportunities for technological solutions that could be beneficial for the user group and their specific needs, and identified technological needs exist, for example, in the areas of health, social connectedness, as well as possibilities for living independently as long as possible (Liu, Stroulia, Nikolaidis, Miguel-Cruz, & Rincon, 2016; Morris et al., 2014; Rogers & Mitzner, 2017).

When seen as a recent technological trend, gamification is often assumed to be more appealing and enjoyable to younger audiences as they commonly have a higher self-efficacy with digital technologies, and more experience with digital games, and are therefore potentially more interested in them (Betts, Hill, & Gardner, 2019; Bittner & Shipper, 2014; Malik, Hiekkanen, Hussain, Hamari, & Johri, 2019; Thiel, Reisinger, & Röderer, 2016). However, prior research has indicated that similar to younger generations, older adults also play and enjoy games (De Schutter, 2011; Hall, Chavarria, Maneeratana, Chaney, & Bernhardt, 2012). Prior research has also concluded that digital gameplay, in general, can provide various benefits for older adults, especially in the health domain (Hall et al., 2012; Kaufman, Sauvé, Renaud, Sixsmith, & Mortenson, 2016; Sood et al., 2019; Zhang & Kaufman, 2016). It is noteworthy that in the next few decades, generations that have engaged with digital technologies, and especially digital games since childhood, will be reaching the thresholds of older adulthood, so further diminishing the so-called digital divide between younger and older users (Raban & Brynin, 2006). Therefore, substantial attention to how gameful interactions could be beneficial for older user groups is warranted.

In the current systematic review, we analyzed the existing body of literature on gamification for older adults. Peer-reviewed studies reporting gameful interventions for older adults of ≥55 years of age, and which reported subjective or objective outcomes related to the user, were considered eligible for inclusion within the review. Based on 12 identified studies, we examined the purposes and outcomes of the gamification, the study design that had been employed, what kind of gamification implementations had been used, and what results had been achieved.

Methods

Search Strategy

This review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement of Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, and Altman (2009). The literature search was conducted in January 2019 employing four key databases (Scopus, Web of Science, OVID PsycINFO, and PubMed). The searches were conducted using search terms covering the terminology presented in Table 1. The specific search strings were formulated according to the search logic of each database, while retaining the same terminology. Table 1 also reports the number of records retrieved from each database.

Table 1.

Literature Search Terminology and Number of Records Retrieved From Databases

| Search terms | |

| gamif* OR gameful* AND aged OR ageing OR aging OR elder* OR “older adult*” OR “older person*” OR “older people” OR senior* OR “senior citizen*” OR geriatric* OR retired OR retiree* OR pensioner* | |

| Database | Number of records |

| Scopus | 241 |

| PubMed | 59 |

| Web of Science | 125 |

| OVID PsycINFO | 248 |

| Total | 673 |

Inclusion Criteria and Study Selection

The study selection process was carried out by two researchers independently. Studies were included if they met the predefined PICOS-criteria based on the research questions: population (adults aged ≥55), intervention (any technology-based game or gamification intervention), comparison (no comparison setting required), type of outcome (subjective or objective outcomes related to the user as a result of involvement/engagement with the intervention), and study design (peer-reviewed studies with analysis of empirical data and written in English).

The decision to use the age of 55 years old instead of higher numbers was taken to widen the scope of the review, as research on gamification for older adults is known to be fairly limited. The concept of “seniority” or “old age” has been defined varyingly across time, different contexts, and among different cultures (Seeman, Lusignolo, Albert, & Berkman, 2001). While the United Nations has agreed the age of 60 to denote old age (United Nations, 2015), in some contexts, even the age of 50 has been used as the lower limit for older age (World Health Organization, 2002). The cut-point of the age of ≥55 years has also been used in previous studies (e.g., Chen & Schulz, 2016; Lehtinen, Näsänen, & Sarvas, 2009; Nef, Ganea, Müri, & Mosimann, 2013).

Research reporting only usability tests or user requirement/preference tests were excluded from the review. Furthermore, all studies identified as having been published under the flag of gamification and that met the inclusion criteria were considered for review without evaluating whether the intervention actually involved a game or gamified solution. The distinction between these two concepts is elusive, and therefore all game or gamification interventions that were retrieved with the search terms were screened for inclusion, based on the above criteria.

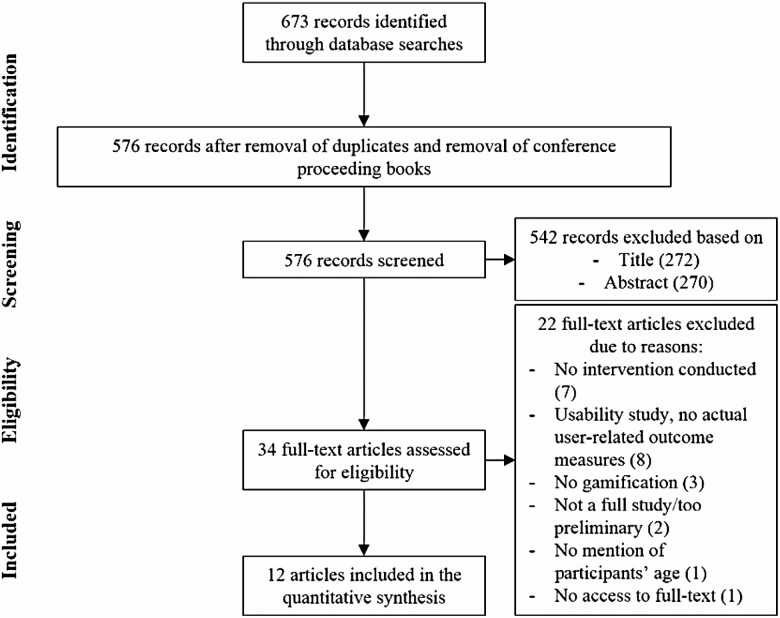

The corresponding author conducted the literature searches. The study selection process was conducted by both authors independently in three separate phases, in order to identify all relevant literature and to minimize errors and bias. After each phase, the selections were cross-checked between the authors, and possible discrepancies were discussed. Through a systematic process of screening the body of literature for eligibility, 12 studies were identified that met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). Both reviewers mutually agreed on the final selection of the studies to be included in this review. The study selection was documented using the RefWorks web-based research management tool and a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet to ensure its repeatability.

Figure 1.

A flowchart describing the systematic review process.

Both authors analyzed the selected studies independently. Extracted data included details about the authors, aim of the study, location of the study, study design, sample characteristics, intervention design, control conditions, modality of the intervention/control (technology used), study outcomes, and author-reported conclusions. The extracted data were cross-checked between authors and discussed in case of discrepancies. The corresponding author synthesized the extracted data for the analysis.

Results

Study Characteristics

All studies with the exception of one aimed at supporting various health aspects via gamification (Table 2). Of the 12 reviewed studies, 5 focused on cognitive health, 4 on physical health, 1 study on both cognitive and physical health, and 1 on mental health. A further study focused on human–computer interaction (HCI; Wagner & Minge, 2015) relating to social interaction conditions and emotional responses, and could thus be considered to address social and mental health.

Table 2.

Study Characteristics

| References | Aim | Domain | Study design | Modality | Participants and technology proficiency (TP) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boot and colleagues (2016) | Examining older adults’ perceptions and attitudes toward game-based interventions after playing digital games on a tablet (experimental or control games) | Cognitive health | A 1-month randomized, controlled experiment. Participants randomized to experimental and control groups. ~45 min sessions of game play/7 times per week in both groups. Game play tracked in a diary. Survey at the end of intervention. | Tablet (Acer Iconia A700) /Game | N = 55, aged 65+ TP: On average low proficiency (18.87 (SD = 9.74) out of 40, on a Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire) | United States |

| Dugas and colleagues (2018) | Investigating via a gamified mHealth tool how individual differences in psychological traits are associated with mHealth effectiveness | Physical health | A 13-week, randomized, controlled pilot study. Patients randomized to control (no app, care as usual) or one of 4 conditions using different versions of the app. | Tablet (Samsung Galaxy Tab 3) and activity monitor (Fitbit One)/mHealth tool | N = 27, veterans with poorly controlled Type 2 diabetes. Mean age = 67.56, SD = 5.81. Gender not reported exactly. TP: not reported. | United States |

| Hiraoka, Wang, and Kawakami (2016) | Proposing and evaluating a game-based cognitive function training system for elderly drivers | Cognitive health | A laboratory study conducted in 7 sessions. Half of the participants trained at home with a tablet in addition to the laboratory sessions, half performed only on-site training in the laboratory. | Tablet/Driving training system | N = 11, elderly males. Mean age = 69.82, SD = 3.57. TP: none of the participants had experience with tablet devices before the study. | Japan |

| Li, Theng, and Foo (2016) | Examining the influence of high and low playfulness exergames on depression | Mental health | A 6-week randomized, controlled study. Participants randomized to two different exergaming conditions. | Gaming console (Nintendo Wii)/Exergame | N = 49, older adults with subthreshold depression. Mean age = 71.12, SD = 8.67; female = 59.20%. TP: not reported. | Singapore |

| Savulich and colleagues (2017) | Examining the effects of cognitive training using a novel memory game developed by the team on patients with a diagnosis of amnestic mild cognitive impairment | Cognitive health | A 4-week randomized, controlled trial with 8 1-hr supervised training sessions. Participants randomized to 2 groups: intervention or care as usual. | Tablet (iPad)/Learning and memory game | N = 42, patients with mild cognitive impairment. Mean age in intervention 75.2, SD = 7.4; in control: 76.9, SD = 8.3. Gender in intervention 11 males, 10 females; in control 14 males, 7 females. TP: Internet usage hr/week Intervention 2.2 hr (SD = 6.6); Control 2.3 hr (SD = 4.5) Computer gameplay hr/week Intervention 0.9 hr (SD = 2.1); Control 0.7 hr (SD = 1.9) Confidence using new technology Intervention: 11 participants very confident; 2 confident; 3 apprehensive; 4 very apprehensive Control: 13 participants very confident; 4 confident; 1 apprehensive; 3 very apprehensive | UK |

| Scase and colleagues (2017) | Examining the adherence to a tablet-based gamified environment designed to promote health and well-being in older people with mild cognitive impairment | Cognitive and physical health | A 47-day intervention where participants living either (i) at a retirement village or (ii) separately across the city were asked to interact with the solution 5 days a week. | Tablet/DOREMI application to promote cognition and exercise | N = 24 (consisting of 2 different samples). Older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Two participants groups (1) N =11, mean age = 75.4, SD = 5.14, 1 male, (2) N = 13, mean age = 74.9, SD = 3.68, 1 male. TP: not reported. | N/A |

| Souders and colleagues (2017) | Examining the difference of using a gamified cognitive training suite compared to playing word and number puzzles in transfer of cognitive effects to similar tasks | Cognitive health | A randomized controlled study, 1-month intervention. Participants randomized to gamified group and active control group. Instructions to play 45 min/d in both groups. Playtime recorded in journals. | Tablet (Acer Iconia A700)/Cognitive training system | N = 60. Mean age = 72.35, SD = 5.20. Males 26, females 34. TP: not reported. | United States |

| Su and Cheng (2016) | Examining the effectiveness of a developed motion-based 3D game in total knee replacement rehabilitation on patient’s self-efficacy | Physical health | A quasi-experiment, 2-month intervention. Participants randomized to intervention condition with the game or to control condition with routine physiotherapy exercises. | Gaming console (Microsoft Kinect)/Rehabilitation system | N = 34. Intervention mean age = 65.88, SD = 4.296, control mean age = 68.56, SD = 2.897. Intervention: female 9, male 9; control: female 9, male 7. TP: Experience in using motion capture tools Intervention: 9 have experience; 9 no experience Control: 6 have experience; 10 no experience | Taiwan |

| Wagner and Minge (2015) | Examining subjective enjoyment and motivational effects of game elements by providing different sociable gameplay conditions | Human–computer interaction | A randomized, controlled laboratory experiment. Participants invited in pairs knowing each other beforehand and randomly assigned to 3 conditions as pairs. | Online dice game on a personal computer | N = 36. Mean age = 69.9, half of the participants were female. TP: not reported. | Germany |

| Katajapuu and colleagues (2017) | Examining the effects of developed exergames on changes in body functions and activity level | Physical health | A 6-week randomized, controlled study. Participants randomized to 3 conditions: intervention with exergames, normal physiotherapy, and control with no activity. | Gaming console (Microsoft Kinect)/Exergames | N = 30. Mean age = 71.34, SD = 6.62. Male 9, female 21. TP: not reported. | Singapore |

| Steinert, Buchem, Merceron, Kreutel, and Haesner (2018) | Examining the usability, acceptance, and effectiveness of a novel wearable-enhanced mHealth system | Physical health | A 4-week pilot study. A training program consisting of 3 training days and 4 recovery days per week. | Smartphone (Nexus 5 or Samsung Galaxy 5) and Activity monitor (Garmin Vivofit) enhanced training system/mHealth system | N = 20. Mean age = 69, age range 62–75 years. TP: Participants had high digital literacy 70% of participants using smartphones frequently; 90% using computers frequently; 90% using the Internet frequently; 30% using a tablet device Technology commitment score Mean 46 points (a 12–60 point scale) showing high technology commitment | Germany |

| Sun, Qiu, and Zuo (2017) | Examining the effect of gamification for improving learning processes and performance for seniors. A system for learning to use a ticket vending machine developed | Cognitive health | A controlled laboratory experiment. Participants in 4 conditions: badge, story, badge + story, and control. | Kiosk (Ticket Vending Machine) | N = 9. Age > 60. Female 8, male 1. TP: none of the participants had used the ticket vending machine before. | China |

In terms of study design, 8 of the 12 studies reported a randomized, controlled study setting. The remaining four studies were also intervention studies, but either the study designs included no randomization or control, or detailed information regarding these points was not provided. The study timeframes ranged from single-session laboratory studies to studies spanning a 13-week period. The average length of studies not limited to one laboratory session was approximately 6 weeks.

The average number of participants in the studies was 33 (Nmin = 9; Nmax = 60), and the sample sizes of the studies are slightly lower than those found in gamification research in general (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019). As described earlier, the review was limited to studies that examined the effectiveness of gamification with older adults of ≥55 years of age. The mean age of the participants was reported in 10 of the 12 studies, with an average mean of 71.38 years of age. The studies were conducted in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, China, and Singapore.

Only four of the reviewed studies reported measuring the technology proficiency or literacy of the participants (Table 2). Steinert and colleagues (2018) reported their participants to have a very high technology literacy and to be frequent users of various information technologies. Savulich and colleagues (2017) described their study participants to be confident in using new technology, although their actual self-reported usage was fairly low. Boot and colleagues (2016) reported that the participants in their study had a low proficiency with mobile technologies. Su and Cheng (2016) described that approximately half of their participants had experience with motion-capturing technology before the study. Furthermore, two of the reviewed studies (Hiraoka et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017) mentioned that participants in their study had no prior experience with the investigated technologies. The remaining six studies did not address the technology proficiency or literacy of their participants.

Gameful Interventions

Half of the studies used a tablet-based solution in their study setting (Table 2), three studies used a gaming console, and one used a smartphone solution. In addition, one study used a game solution on a desktop computer, and one study focused on the use of a ticket vending machine. In most of the studies, the gameful solution had been developed by the research team. The only commercially available solution employed was Wii Fit exergames (Li et al., 2016).

There was a large amount of variation in the gameful elements included in the reviewed studies (Supplementary Appendix). The most common elements were (i) different types of adaptive or increasing difficulty based on the player progress, (ii) social elements, (iii) scores and points, (iv) clear goals, and (v) various progress indicators. The prevalence of differing means of gauging the player level, and thus the difficulty of the game, is an intuitively understandable element in the context of older adults, especially for games requiring physical movement. The other commonly included gameful elements in the reviewed studies correspond largely to elements that are frequently seen in gamification research (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019).

As suggested by the wide variety of study aims (Table 2), the aims and functions of the gameful interventions varied substantially (Supplementary Appendix). Of the 12 reviewed studies, 4 investigated the effects of interventions containing various gamified cognitive function tasks. The intervention participants in the studies by Boot and colleagues (2016) and Souders and colleagues (2017) worked, for example, on gamified memory and reasoning tasks, while the control group played common games such as crossword puzzles and Sudoku. Savulich and colleagues (2017), on the other hand, studied the effects of cognitive training games presented in the form of a game show with rounds, in-game prizes, and a “host” that encourages the player to continue. A very specific cognitive health-targeting gameful intervention was reported by Hiraoka and colleagues (2016), whose intervention consisted of a trail making game with the goal of rehabilitating the visual attention ability of elderly drivers.

Physical health was targeted in four studies, of which three used body-controlled exergames in their interventions. Li and colleagues (2016) studied the effects of playfulness in exergames on depression using Wii Fit Sports exergames and Wii Fit fitness exercises. Katajapuu and colleagues (2017) and Su and Cheng (2016) reported studies using Microsoft Kinect to capture the movements of the players that then controlled the exergame. Physical health was also targeted in the study by Steinert and colleagues (2018); however, their intervention more resembled the common gamified exercise solutions delivered via mobile devices, with the participants carrying an activity tracker and performing exercises provided by the mHealth solution.

More varied health benefits were examined in studies by Dugas and colleagues (2018) and Scase and colleagues (2017). Dugas and colleagues targeted diabetes control in their intervention, and in consequence, also addressed physical exercise and healthy nutrition in the solution. The gamification was built around common achievement-oriented game-based features such as score and goals, but also included social elements in the form of engagement with peers and/or clinicians depending on the intervention conditions. The study by Scase and colleagues (2017) focused on cognitive, physical, and social health, as well as health nutrition, which were supported, for example, by mini-games, instructions, and challenges provided by the studied solution.

Finally, two interventions focused on investigating the effects of specific gameful elements in different contexts. Wagner and Minge (2015) focused on studying the effects of different social gameplay conditions on participant motivation and enjoyment, based on a game of Yahtzee. Furthermore, Sun and colleagues (2017) examined the effects of achievement- and immersion-oriented game elements, namely badges and storyline, applied to a system teaching elderly users how to use a local ticket vending machine.

The training provided to study participants regarding the gameful interventions varied greatly between the reviewed studies. Studies with exergames or a physiotherapeutic intervention, as well as some of the cognitive training studies, were conducted under supervision in a lab setting, which diminishes the need for participant training. Therefore, some of the studies did not specify in detail how the participants were prepared for the intervention. Studies that consisted of participants interacting with the intervention solution on their own reported conducting training sessions for the participants (Boot et al., 2016; Dugas et al., 2018; Scase et al., 2017; Souders et al., 2017; Steinert et al., 2018). However, the level of detail in reporting the training varied greatly among these studies. For example, Boot and colleagues (2016) only mention that participants received initial training on how to access the games, and Scase and colleagues (2017) report that a training period of 17 days took place, but do not provide further details. In contrast, Dugas and colleagues (2018) report holding a 2-hr group training session during which the participants were introduced to all aspects of the gameful intervention, and depending on their experimental group, to the specific features of that group. Some of the studies also described the user support provided to participants during the study, for example, a handbook and technology support made accessible by phone (Steinert et al., 2018).

Intervention Outcomes

The outcomes of the reviewed studies focused mainly on various health outcomes (Table 3). In the body of literature, 13 different kinds of physical health outcomes were studied across four studies; 10 different outcomes related to cognitive abilities across four studies, and 8 outcomes related to mental states and emotions across four studies. Furthermore, three studies included seven other health-related outcomes or behaviors that were not able to be categorized under the main health categories.

Table 3.

Outcomes Examined in the Studies

| Categorya | Studies | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health | Dugas and colleagues (2018) | Exercise |

| Su and Cheng (2016) | Function score (situational walking conditions; stair climbing; use of walking aids); American Knee Society Score | |

| Katajapuu and colleagues (2017) | Physical activity; physical performance; handgrip muscle force; balance | |

| Steinert and colleagues (2018) | PAQ 50+; balancing ability; hand and leg strength; self-assessment of motoric skills; confidence in moving; endurance | |

| Cognitive abilities | Boot and colleagues (2016) | Perception of improved perceptual and cognitive abilities |

| Hiraoka and colleagues (2016) | Hazard perception ability | |

| Savulich and colleagues (2017) | Episodic memory and new learning; visuospatial memory; choice reaction time | |

| Souders and colleagues (2017) | Cognitive battery; reasoning ability; processing speed; memory; executive control | |

| Mental state and emotions | Li and colleagues (2016) | Depression; positive emotions |

| Savulich and colleagues (2017) | Depression; apathy; hospital anxiety and depression; mental state | |

| Wagner and Minge (2015) | Emotional enjoyment; valence | |

| Other health outcomes/behaviors | Dugas et al. (2018) | Tracking of glucose control; nutrition; medication adherence |

| Hiraoka and colleagues (2016) | Degree of useful field of view | |

| Steinert and colleagues (2018) | Sleep quality; body composition; subjective health status; training compliance | |

| Motivation | Boot and colleagues (2016) | Motivation |

| Wagner and Minge (2015) | Motivation | |

| Savulich and colleagues (2017) | Motivation | |

| Steinert and colleagues (2018) | Motivation to be active | |

| Sun and colleagues (2017) | Intrinsic motivation; perceived autonomy | |

| Solution adherence/usage | Boot and colleagues (2016) | Adherence |

| Scase and colleagues (2017) | Adherence; amount of use | |

| Souders and colleagues (2017) | Adherence | |

| Steinert and colleagues (2018) | System usage | |

| Perceptions regarding the technology | Boot and colleagues (2016) | Game perceptions |

| Su and Cheng (2016) | System usability | |

| Steinert and colleagues (2018) | Usability; acceptance | |

| Sun and colleagues (2017) | Technology anxiety | |

| Test performance | Hiraoka and colleagues (2016) | Training performance; safe driving performance |

| Sun and colleagues (2017) | Learning performance (time use in final test) | |

| Self-efficacy | Li and colleagues (2016) | Self-efficacy |

| Su and Cheng (2016) | Self-efficacy in rehabilitation | |

| Sun and colleagues (2017) | Perceived competence |

aContains both objectively and subjectively measured outcomes.

Gamification has been commonly considered as a means to increase engagement and motivation to use systems and services (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019). Among the reviewed studies, outcomes related to engagement and motivation were frequently seen (Table 3; Supplementary Appendix). Five of the 12 studies investigated engagement with the gameful solution, or a health behavior in the form of either adherence (Boot et al., 2016; Dugas et al., 2018; Scase et al., 2017; Souders et al., 2017) or compliance (Steinert et al., 2018). Furthermore, five studies examined participants’ motivation (Boot et al., 2016; Savulich et al., 2017; Steinert et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2017; Wagner & Minge, 2015) to continue playing the intervention game or continue with a training program.

The adherence to the use of gameful solutions or to health behaviors was generally reported to be good or acceptable during the study timeframe. However, Boot and colleagues (2016) report that while the adherence to the intervention was good, the intervention group actually found the solution they were using less enjoyable and more frustrating than the control group. On the other hand, Scase and colleagues (2017) compared the adherence to the gameful solution between two user groups with different living arrangements: seniors living in a retirement village and seniors living separately across the city. In their study, the group living in a retirement village engaged three times more with the solution than the group consisting of seniors living separately. As the gameful solution studied by Scase and colleagues (2017) encourages social activity, it is intuitively understandable that the proximity of social relations at the retirement village might have led to a higher adherence with the gameful solution as well.

Intervention Effects

The intervention results were analyzed and categorized as either strong positive, weak positive, null, weak negative, or strong negative depending on whether the tests conducted had yielded positively or negatively significant effects (Supplementary Appendix). If all the tests reported in a study showed positive significant effects, the results were categorized as strong positive; if most of the tests showed positive significant effects, but some might have shown nonsignificant results or significant negative effects, the results were considered as weak positive. No significant effects was categorized as null results. The negative results were categorized following the same logic.

The reviewed studies reported mostly positively oriented effects from the interventions. Only one study showed strong positive results by reporting positive significant effects for all of the relationships examined in the study (Hiraoka et al., 2016), while nine of the reviewed studies were categorized as reporting weak positive results. Additionally, one study reported null results where none of the studied relationships had significant effects (Katajapuu et al., 2017), and one study reported weak negative effects (Boot et al., 2016).

Based on the results of the reviewed studies, gamification and game solutions can be beneficial for the given user group in the context of visual attention rehabilitation (Hiraoka et al., 2016), where the gameful intervention improved, for example, the detection rate of peripheral targets, degree of useful field of view, and hazard perception ability. Positive results were also reported in the context of diabetes control with a gamified application (Dugas et al., 2018), on increasing positive emotions via playful exergames in patients with subthreshold depression (Li et al., 2016), on gameful cognitive training of patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (Savulich et al., 2017), and on the engagement of older adults with mild cognitive impairment with a gamified training program (Scase et al., 2017).

Furthermore, positively oriented results were reported on the effects of exergames on knee movement scores and perceptions of self-efficacy for total knee replacement patients (Su & Cheng, 2016), on the motivational effects and increased positive emotions of social gameplay conditions (Wagner & Minge, 2015), on increased physical activity and balancing ability from a gameful mHealth solution (Steinert et al., 2018), and on increased learning performance and autonomy experiences using a gameful ticket vending machine training (Sun et al., 2017). The study by Souders and colleagues (2017) found mild positive improvement on memory test scores after cognitive training game play, but this effect was noted to be weak.

No significant results were reported on the effects of exergames on physical activity, balance, physical performance, or handgrip muscle force in the study by Katajapuu and colleagues (2017). Negatively oriented results were reported in the study by Boot and colleagues (2016) where the participants, in fact, found the experimental cognitive training games to be less enjoyable and more frustrating than traditional puzzle games.

Discussion

The aim of this literature review was to investigate the current body of literature on gamification for older adults. Altogether, 12 studies with gameful interventions directed at older adults of ≥55 years of age and that reported user-related outcomes were identified. Given the tremendous popularity of gamification research in recent years (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019), the small number of studies addressing senior users indicates that previous research has focused heavily on younger demographics, and neglected the growing user group of older adults.

The findings of the review indicate that there are differences in the research foci as well as the gamification solutions implemented in the published studies, based on whether the focus is specifically on older adults, on the younger generation, or adults in general. Firstly, the gamification research focused on older adults has a strong thematic focus. Based on the findings of the current review, all of the reviewed studies were in the health domain, with the exception of one study focusing on HCI. This is in contrast to the breadth of domains explored in the gamification research field in general (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019). In the current review, cognitive health along with physical health were the most frequently studied topics, which is understandable given that older age is characterized by declines in these areas. Only one study addressed gamification for mental health; a domain that has otherwise been rather widely targeted by research and practice (Fleming et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2016). Secondly, another aspect in which gamification solutions for seniors are in contrast to the gamification research in general (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019) is the prevalence of adaptive or increasing difficulty elements. However, the prominence of these types of elements is an understandable choice when designing solutions for older adults, especially in the context of games that require physical movement.

As the general interest toward, for example, mHealth technologies focusing on older adults is increasing (Becker et al., 2015; Changizi & Kaveh, 2017; McMahon et al., 2016), the positively oriented findings of this review suggest that gameful interactions can be a viable and encouraging way of supporting the adoption of these types of technologies among this cohort. As indicated by Dugas and colleagues (2018), personality differences can also have a significant impact on how certain gamification features such as goals can affect the use of mHealth technologies for older adults. Thus, due to the varying needs, physical and psychological characteristics and conditions of the potential users of these technologies, further research is needed to create a better understanding of the underlying motivations, challenges, and design solutions required for different populations.

Given the ongoing demographic shift, the existing technological needs and opportunities extend to domains beyond health. A considerable amount of research is being conducted, for example, on supporting the possibilities of seniors to live independently long as possible with the help of various smart home, monitoring, or assistive technologies (Liu et al., 2016; Yusif, Soar, & Hafeez-Baig, 2016). While the gamification of smart home or monitoring technologies was not directly explored in the reviewed studies, the results reported by Dugas and colleagues (2018) suggest that gamification can support older adults, for example, in the self-management of their health status, and could potentially help with monitoring seniors who live independently. With the increase of cloud computing and constant connectivity, as well as the rise of machine learning solutions, more intelligent tools for supporting the safety and well-being of older adults to live independently can be developed. Gamification could therefore be employed in these domains (and others) to increase the acceptability and willingness to engage with emerging technologies.

Furthermore, as loneliness among older adults is a major concern due to its known detrimental effects on health (Barg et al., 2006; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, & Stephenson, 2015), various technological solutions have been examined as a tool for increasing interpersonal communication and relations among older adults (Chopik, 2016). As indicated by the reviewed study by Scase and colleagues (2017), gamification can increase the level of social activity among older adults, especially in environments where social contacts are readily available such as retirement homes or communities. Accordingly, we would also encourage harnessing gamification for supporting a wider range of facets of senior well-being (Demiris, Thompson, Reeder, Wilamowska, & Zaslavsky, 2013). As games as a medium are well-equipped to convey narratives and support meaning-making, addressing, for example, spiritual well-being by increasing senses of purpose and meaning for older adults via different study-driven and immersive elements could also be explored (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019).

Regarding the gameful interventions employed in the reviewed studies, in most cases, the gamification solution was developed for the purposes of the study and focused on individual achievements supported via feedback on task performance. Only a few studies included any kind of social elements to support social interaction. The details of the gamification interventions featured in the current review largely corresponded to the details of gamification interventions identified in gamification research in general (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019). Moreover, almost all of the reviewed studies focused on single-purpose mHealth applications (such as applications for medication adherence, exercise, or rehabilitation), and with minimal or highly limited interactions with other systems. Given recent technological advancements such as contemporary data-driven technologies and patient support systems, gamification could be extended into integrated mHealth (linking elderly with health care professionals) and social mHealth (connecting formal and informal social networks) solutions. Recent works emerging within the field of HCI emphasize the significance of involving, for example, pertinent caregivers together with the targeted users of the given technological solution, in order to ensure its feasibility, utility, and acceptability (Hoffman et al., 2019; Merkel & Kucharski, 2019). Given the lack of reporting on the collaborations with informal and formal caregivers (e.g., family members, physicians, nursing personnel, social workers, and physical/recreational therapists) in most of the reviewed studies, involving the caregiver network to better inform the design and implementation of gamified solutions could be a valuable development. Especially, incorporating caregiver networks in the use of such technologies could potentially lead to an elevated perception of social and emotional support, as well as a higher acceptance of the given intervention.

Most of the interventions within the observed studies were delivered through tablet devices. Prior research has indicated that learning to master the use of new technologies such as tablet computers can enhance certain aspects of cognitive functioning for older adults (Chan, Haber, Drew, & Park, 2016). Tablet devices have obvious benefits in terms of, for example, screen size and clarity, but also features that can be perceived as negative or confusing, such as weight, buttons, and keyboard (Vaportzis, Clausen, & Gow, 2017). Less common technologies used in the interventions featured in this review were activity monitors or sensors and smartphones, which could provide more varied gamification opportunities. The data provided by activity monitors and sensors can also be more efficient compared with other forms of gameful feedback for engaging certain user groups. This was suggested by Steinert and colleagues (2018), who noted that the older adults were more motivated by the tangible information provided by the activity monitors than by more abstract gameful feedback. Therefore, evaluating the differences in delivery, context, and effectiveness of different modalities, and benchmarking novel technological devices employing gamified elements could support broadening the domain further.

The focus of this review was on intervention studies without restrictions regarding study settings; however, most of the studies had employed a randomized controlled design. While randomized controlled trials (RCT) potentially provide the most reliable evidence on the effectiveness of a given intervention, there are numerous factors affecting the reliability of these studies, and thus missing details in the research reports can make evaluating the results more difficult. As this review was not limited to RCTs, a proper quality evaluation of the studies was not conducted. However, on an anecdotal level, it can be said that several studies lacked, for example, information on the blinding practices regarding randomization, and this decreases the rigor of the study settings and resultant findings. Future research on gamification for older adults is encouraged to employ RCT and pragmatic RCT settings (Mullins, Whicher, Reese, & Tunis, 2010), and attention should be paid to reporting the details of the study designs, including their blinding practices.

Furthermore, some common methodological shortcomings were noted among the reviewed studies. Many of the studies had employed short intervention times and involved a low number of study participants (Boot et al., 2016; Dugas et al., 2018; Hiraoka et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Scase et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2017), which has been seen as a common challenge within empirical gamification research. Larger sample sizes and longer intervention times would be beneficial for the generalizability of data, as well as providing increased opportunities for identifying, for example, usage patterns and preferences. Moreover, more detailed information regarding the participants (especially in the case of older adults) should be reported. In the reviewed literature, half of the reviewed studies did not address or report the participants in any detail, for example, how experienced the study participants were with information technology. Finally, the analyzed literature exhibits a wide array of outcome measures, and most of those outcomes are examined only by a single study, which makes it challenging to congregate knowledge in the area. In line with seminal literature on gamification research (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019; Morschheuser, Hamari, Koivisto, & Maedche, 2017), the use of validated, established measurement instruments would be beneficial for future research.

Limitations

For this review, 12 studies were identified as being eligible for inclusion, based on the set study criteria. Despite the small amount of literature, we are confident that the identified studies represent the current body of literature published under the flag of gamification and focusing on older adults. As several prior literature reviews have investigated the health benefits and impact of video games for older adults, we have chosen not to widen the scope of the current review to include games on a more general level.

Due to the small number of studies conducted on gamification for older adults, and the consequential lack of data and results on specific outcomes, it is not yet possible to state with high levels of confidence which outcomes gamification could be most beneficial for within the given user group. Therefore, it is important that future research looks to use validated instruments for the measurement of outcomes, in order to develop a coherent body of knowledge on such outcomes. In addition to the use of measurement instruments, a detailed reporting of the use of gameful interventions will benefit the evaluation of any study outcomes and results.

Furthermore, it is possible that publication bias favoring the publication of studies with positive results has affected the kind of research that gets published, and consequently, the results of the current review. However, this is an identified phenomenon related to publication practices on a general level, and thus affects all research. While it is close to impossible to state whether publication bias has affected the reviewed body of literature, the possibility of it affecting the findings should be taken into account when evaluating the results of the review.

As is evident with literature reviews, by the time of publication, it is common that some new relevant works will have already appeared regarding the topic of the review. Therefore, we encourage conducting systematic literature reviews periodically on the topic of gamification for seniors, to map the accumulated and up-to-date knowledge.

Conclusions

The findings of this review focusing on the impact of gameful interventions for older adults suggest that senior users may benefit from gamification and game-based interventions. Most of the research has focused on the health domain, in particular, physiological, mental, and cognitive functions, and the findings reported in the reviewed studies are mainly positively oriented. Therefore, based on the available evidence, we conclude that gamification holds potential for older adults, especially in health-related contexts. However, methodological shortcomings in the reviewed literature as well as the generally limited amount of research that focuses on gamification and older adults should be taken into account when evaluating the results. Future research is encouraged to further examine the possibilities of implementing gamification in technological solutions which target older adults in various domains, such as social well-being and supporting independent living. Finally, in order to strengthen the existing body of evidence and establish solid grounding on the impacts of gamification on older adults, future work should incorporate appropriate theoretical frameworks, and employ rigorous study settings including proper randomization and controlling practices, larger sample sizes, longitudinal studies, and the use of validated measurement instruments to ensure the quality and reliability of the results.

Funding

This research has been supported by a grant from Business Finland (376/31/2018). The funder has not influenced the design, conduct, analysis, or reporting of the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Barg, F. K., Huss-Ashmore, R., Wittink, M. N., Murray, G. F., Bogner, H. R., & Gallo, J. J. (2006). A mixed-methods approach to understanding loneliness and depression in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(6), S329–S339. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.6.s329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S., Brandl, C., Meister, S., Nagel, E., Miron-Shatz, T., Mitchell, A.,Mertens, A. (2015). Demographic and health related data of users of a mobile application to support drug adherence is associated with usage duration and intensity. PLoS One, 10(1), e0116980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts, L. R., Hill, R., & Gardner, S. E. (2019). “There’s not enough knowledge out there”: Examining older adults’ perceptions of digital technology use and digital inclusion classes. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 38(8), 1147–1166. doi: 10.1177/0733464817737621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner, J., & Schipper, J. (2014). Motivational effects and age differences of gamification in product advertising. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(5), 391–400. doi: 10.1108/JCM-04-2014-0945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boot, W.R., Souders, D., Charness, N., Blocker, K., Roque, N., & Vitale, T. (2016). The gamification of cognitive training: Older adults’ perceptions of and attitudes toward digital game-based interventions. In Zhou J., & Salvendy G. (Eds.), Human aspects of IT for the aged population. Design for aging. ITAP 2016. Lecture notes in computer science (Vol. 9754, pp. 290–300). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39943-0_28 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M. Y., Haber, S., Drew, L. M., & Park, D. C. (2016). Training older adults to use tablet computers: Does it enhance cognitive function? The Gerontologist, 56(3), 475–484. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changizi, M., & Kaveh, M. H. (2017). Effectiveness of the mHealth technology in improvement of healthy behaviors in an elderly population—A systematic review. mHealth, 3, 51. doi: 10.21037/mhealth.2017.08.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. R., & Schulz, P. J. (2016). The effect of information communication technology interventions on reducing social isolation in the elderly: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(1), e18. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopik, W. J. (2016). The benefits of social technology use among older adults are mediated by reduced loneliness. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 19(9), 551–556. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja, S. J., & Lee, C.C., (2009). Information technology and older adults. In Sears, A., & Jacko, J. A., (Eds.), Human–computer interaction: Designing for diverse users and domains (pp. 18–30). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. doi: 10.1201/9781420088885.ch2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Schutter, B. (2011). Never too old to play: The appeal of digital games to an older audience. Games and Culture, 6(2), 155–170. doi: 10.1177/1555412010364978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demiris, G., Thompson, H. J., Reeder, B., Wilamowska, K., & Zaslavsky, O. (2013). Using informatics to capture older adults’ wellness. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 82(11), e232–e241. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, S. (2015). The lens of intrinsic skill atoms: A method for gameful design. Human–Computer Interaction, 30(3–4), 294–335. doi: 10.1080/07370024.2014.993471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning future media environments (pp. 9–15). New York (NY): ACM. doi: 10.1145/2181037.2181040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas, M., Crowley, K., Gao, G. G., Xu, T., Agarwal, R., Kruglanski, A. W., & Steinle, N. (2018). Individual differences in regulatory mode moderate the effectiveness of a pilot mHealth trial for diabetes management among older veterans. PLoS One, 13(3), e0192807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, T. M., Bavin, L., Stasiak, K., Hermansson-Webb, E., Merry, S. N., Cheek, C.,Hetrick, S. (2016). Serious games and gamification for mental health: Current status and promising directions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7, 215. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. K., Chavarria, E., Maneeratana, V., Chaney, B. H., & Bernhardt, J. M. (2012). Health benefits of digital videogames for older adults: A systematic review of the literature. Games for Health Journal, 1(6), 402–410. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2012.0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J. (2013). Transforming homo economicus into homo ludens: A field experiment on gamification in a utilitarian peer-to-peer trading service. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 12(4), 236–245. doi: 10.1016/j.elerap.2013.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R., Betts, L. R., & Gardner, S. E. (2015). Older adults’ experiences and perceptions of digital technology: (Dis)empowerment, wellbeing, and inclusion. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka, T., Wang, T. W., & Kawakami, H. (2016). Cognitive function training system using game-based design for elderly drivers. IFAC-PapersOnLine, 49(19), 579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ifacol.2016.10.613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, A. S., Bateman, D. R., Ganoe, C., Punjasthitkul, S., Das, A. K., Hoffman, D. B.,…Bennett, A. (2019). Development and field testing of a long-term care decision aid website for older adults: Engaging patients and caregivers in user-centered design [published online ahead of print November 27, 2019]. The Gerontologist. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huotari, K., & Hamari, J. (2017). A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electronic Markets, 27(1), 21–31. doi: 10.1007/s12525-015-0212-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D., Deterding, S., Kuhn, K. A., Staneva, A., Stoyanov, S., & Hides, L. (2016). Gamification for health and wellbeing: A systematic review of the literature. Internet Interventions, 6, 89–106. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katajapuu, N., Luimula, M., Theng, Y. L., Pham, T. P., Li, J., Pyae, A., & Sato, K. (2017). Benefits of exergame exercise on physical functioning of elderly people. In Proceedings of 8th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom) (pp. 85–90). New York (NY): IEEE. doi: 10.1109/coginfocom.2017.8268221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, D., Sauvé, L., Renaud, L., Sixsmith, A., & Mortenson, B. (2016). Older adults’ digital gameplay: Patterns, benefits, and challenges. Simulation & Gaming, 47(4), 465–489. doi: 10.1177/1046878116645736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2014). Demographic differences in perceived benefits from gamification. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.10.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtinen, V., Näsänen, J., & Sarvas, R. (2009). A little silly and empty-headed: Older adults’ understandings of social networking sites. In Proceedings of the 2009 British Computer Society Conference on Human–Computer Interaction, BCS-HCI 2009 (pp. 45–54). Swinton: British Computer Society. doi: 10.14236/ewic/hci2009.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Theng, Y. L., & Foo, S. (2016). Exergames for older adults with subthreshold depression: Does higher playfulness lead to better improvement in depression? Games for Health Journal, 5(3), 175–182. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2015.0100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L., Stroulia, E., Nikolaidis, I., Miguel-Cruz, A., & Rios Rincon, A. (2016). Smart homes and home health monitoring technologies for older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 91, 44–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A., Hiekkanen, K., Hussain, Z., Hamari, J., & Johri, A. (2019). How players across gender and age experience Pokémon Go? Universal Access in the Information Society, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10209-019-00694-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, S. K., Lewis, B., Oakes, M., Guan, W., Wyman, J. F., & Rothman, A. J. (2016). Older adults’ experiences using a commercially available monitor to self-track their physical activity. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(2), e35. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.5120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, S., & Kucharski, A. (2019). Participatory design in gerontechnology: A systematic literature review. The Gerontologist, 59(1), e16–e25. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G.; PRISMA Group . (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M. E., Adair, B., Ozanne, E., Kurowski, W., Miller, K. J., Pearce, A. J.,…Said, C. M. (2014). Smart technologies to enhance social connectedness in older people who live at home. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 33(3), 142–152. doi: 10.1111/ajag.12154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morschheuser, B., Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Maedche, A. (2017). Gamified crowdsourcing: Conceptualization, literature review, and future agenda. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 106, 26–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2017.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, C. D., Whicher, D., Reese, E. S., & Tunis, S. (2010). Generating evidence for comparative effectiveness research using more pragmatic randomized controlled trials. Pharmacoeconomics, 28(10), 969–976. doi: 10.2165/11536160-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nef, T., Ganea, R. L., Müri, R. M., & Mosimann, U. P. (2013). Social networking sites and older users—A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(7), 1041–1053. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raban, Y., & Brynin, M. (2006). Older people and new technologies. In Kraut, R., Brynin, M., & Kiesler, S. (Eds.), Computers, phones, and the Internet: Domesticating information technology (pp. 43–50). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, W. A., & Mitzner, T. L. (2017). Envisioning the future for older adults: Autonomy, health, well-being, and social connectedness with technology support. Futures, 87, 133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., Rigby, C. S., & Przybylski, A. (2006). The motivational pull of video games: A self-determination theory approach. Motivation and Emotion, 30(4), 344–360. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9051-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savulich, G., Piercy, T., Fox, C., Suckling, J., Rowe, J. B., O’Brien, J. T., & Sahakian, B. J. (2017). Cognitive training using a novel memory game on an iPad in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI). The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 20(8), 624–633. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyx040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scase, M., Marandure, B., Hancox, J., Kreiner, K., Hanke, S., & Kropf, J. (2017). Development of and adherence to a computer-based gamified environment designed to promote health and wellbeing in older people with mild cognitive impairment. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 236, 348–355. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-759-7-348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaborn, K., & Fels, D. I. (2015). Gamification in theory and action: A survey. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies, 74, 14–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman, T. E., Lusignolo, T. M., Albert, M., & Berkman, L. (2001). Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health Psychology, 20(4), 243–255. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman, C. K., & Rider, E. A. (2014). Life-span human development (8th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Sood, P., Kletzel, S. L., Krishnan, S., Devos, H., Negm, A., Hoffecker, L.,…Heyn, P. C. (2019). Nonimmersive brain gaming for older adults with cognitive impairment: A scoping review. The Gerontologist, 59(6), e764–e781. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souders, D. J., Boot, W. R., Blocker, K., Vitale, T., Roque, N. A., & Charness, N. (2017). Evidence for narrow transfer after short-term cognitive training in older adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 9, 41. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, A., Buchem, I., Merceron, A., Kreutel, J., & Haesner, M. (2018). A wearable-enhanced fitness program for older adults, combining fitness trackers and gamification elements: The pilot study fMOOC@Home. Sport Sciences for Health, 14(2), 275–282. doi: 10.1007/s11332-017-0424-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su, C., & Cheng, C. (2016). Developing and evaluating creativity gamification rehabilitation system: The application of PCA-ANFIS based emotions model. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 12(5), 1443–1468. doi: 10.12973/eurasia.2016.1527a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K., Qiu L., & Zuo M. (2017). Gamification on senior citizen’s information technology learning: The mediator role of intrinsic motivation. In Zhou J., & Salvendy G. (Eds.), Human aspects of IT for the aged population. Aging, design and user experience. ITAP 2017. Lecture notes in computer science (Vol. 10297, pp. 461–476). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, S. K., Reisinger, M., & Röderer, K. (2016). I’m too old for this!: Influence of age on perception of gamified public participation. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia (pp. 343–346). New York (NY): ACM. doi: 10.1145/3012709.3016073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . (2015). World Population Ageing 2015 (ST/ESA/SER.A/390). Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . (2017). World Population Ageing 2017 (ST/ESA/SER.A/408). Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Vaportzis, E., Clausen, M. G., & Gow, A. J. (2017). Older adults perceptions of technology and barriers to interacting with tablet computers: A focus group study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1687. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vroman, K. G., Arthanat, S., & Lysack, C. (2015). “Who over 65 is online?” Older adults’ dispositions toward information communication technology. Computers in Human Behavior, 43, 156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, I., & Minge, M. (2015). The gods play dice together: The influence of social elements of gamification on seniors’ user experience. In Stephanidis C. (Ed.), HCI International 2015—Posters’ extended abstracts. HCI 2015. Communications in computer and information science (Vol. 528, pp. 334–339). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2002). Proposed working definition of an older person in Africa for the MDS Project. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/

- Yusif, S., Soar, J., & Hafeez-Baig, A. (2016). Older people, assistive technologies, and the barriers to adoption: A systematic review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 94, 112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F., & Kaufman, D. (2016). Physical and cognitive impacts of digital games on older adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35(11), 1189–1210. doi: 10.1177/0733464814566678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.