Abstract

We have found that daily subcutaneous injection with a maximum tolerated dose of the mGluR2/3 agonist LY379268 (20 mg/kg) beginning at 4 weeks of age dramatically improves the motor, neuronal and neurochemical phenotype in R6/2 mice, a rapidly progressing transgenic model of Huntington’s disease (HD). We also previously showed that the benefit of daily LY379268 in R6/2 mice was associated with increases in corticostriatal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and in particular was associated with a reduction in enkephalinergic striatal projection neuron loss. In the present study, we show that daily LY379268 also rescues expression of BDNF by neurons of the thalamic parafascicular nucleus in R6/2 mice, which projects prominently to the striatum, and this increase too is linked to the rescue of enkephalinergic striatal neurons. Thus, LY379268 may protect enkephalinergic striatal projection neurons from loss by boosting BDNF production and delivery via both the corticostriatal and thalamostriatal projection systems. These results suggest that chronic treatment with mGluR2/3 agonists may represent an approach for slowing enkephalinergic neuron loss in HD, and perhaps progression in general.

Keywords: Huntington’s Disease, Therapy, mGluR2/3, Striatum, BDNF

Introduction

We have found that daily subcutaneous injection with a maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of the Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist LY379268 (20mg/kg), which targets metabotropic glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2) and metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (mGluR3), beginning at 4 weeks of age, dramatically improves the phenotype in R6/2 mice, a transgenic model of Huntington’s disease (HD) (1). For example, this regimen prevents a 15–20% striatal neuron loss and severe motor impairment otherwise seen at 10 weeks of age in R6/2 mice. A prior study of ours showed that the benefit of daily LY379268 in R6/2 mice was associated with significant restoration of BDNF production by corticostriatal neurons, which was correlated with the improved survival of enkephalinergic indirect pathway type striatal projection neurons (2). These findings are consistent with the evidence that cortical BDNF production and delivery to striatum is substantially reduced in human HD and in transgenic HD mice (3, 4, 5), that such diminished cortical production of BDNF harms striatum (6, 7, 8), and that intrastriatal BDNF delivery or selective forebrain overexpression of BDNF reverse cortical and striatal pathology and improve motor performance in transgenic HD mice (7, 9, 10, 11). The thalamostriatal neurons of the parafascicular nucleus (PFN), however, also produce BDNF, have a substantial projection to striatum (12, 13), and together with the dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) account for about 35% of striatal BDNF (6, 14, 15). As BDNF expression in PFN neurons is progressively reduced in R6/2 mice (15) and PFN neurons undergo degeneration during the course of HD (16), the resulting reduction in thalamostriatal BDNF may contribute to HD pathogenesis. In the present study, we used in situ hybridization histochemistry (ISHH) to examine BDNF expression in PFN in 10-week old R6/2 mice (to confirm its reduction), and determined if chronic LY379268 treatment reversed any observed deficit in BDNF expression by PFN. We focused on PFN because its contribution to striatal BDNF appears greater than that of SNc (14, 15, 17), and because of its substantial input to striatal projection neurons relative to the cortical input (12, 13). We found that BDNF expression in PFN was, in fact, significantly reduced in R6/2 mice at 10-weeks of age. Moreover, we observed that daily LY379268 treatment via subcutaneous injection significantly improves parafascicular BDNF expression and this improvement appeared to contribute to the rescue of enkephalinergic (ENK+) striatal projection neurons seen with daily LY379268 in R6/2 mice (2). These results further support the view that chronic treatment with mGluR2/3 agonists may represent an approach for slowing HD progression.

Material and Methods

R6/2 mice were used in this study because they replicate the preferential enkephalinergic striatal projection neuron vulnerability of human HD, and because their rapid progression provides a useful initial screen of therapy benefit (1, 2). R6/2 mice were maintained from founders obtained from JAX (strain # 006494) (Bar Harbor, ME), by breeding R6/2 mice with CBA × C57BL/6 F1 (B6CBAF1) mice. Genotype and CAG repeat length were determined by PCR-based amplification using genomic DNA extracted from tail biopsies and carried out by the Laragen Corporation (Culver City, CA). Mice received either 20 mg/kg LY379268 or vehicle (physiological saline) daily at about noon by subcutaneous (sc) injection on their rump, beginning during the fourth week of life after genotyping and group assignment. Both R6/2 mutant and WT littermate males and females treated with vehicle (WTV and R62V) or LY379268 (WTLY and R62LY) were studied by ISHH assessment of perikaryal BDNF levels in PFN in vehicle-treated mice, and of LY379268 efficacy in increasing expression of BDNF in PFN neurons and mitigating loss of striatal ENK+ neurons in R6/2 mice. Brain tissue sections from 53 mice that had been used in Reiner et al., 2012 (2), plus 38 additional mice, were used here for the PFN analysis. Details on animal numbers per treatment group are provided in the Results section. Males and females were used in largely equal numbers per group, and results did not differ notably between males and females. Repeat length was 126.6 CAG for mutants, and did not differ between vehicle- or LY379268-treated R6/2 mice, or males and females. BDNF data for perikarya in layer 5 of primary (M1) motor cortex and data on striatal ENK+ neuron abundance from our prior study (2) are used here again for assessing the contribution of thalamic PFN expression of BDNF to the LY379268 benefit for enkephalinergic striatal neuron survival relative to the role of corticostriatal BDNF. Based on our prior findings (1, 2), it is likely that the reduced numbers of ENK+ striatal neurons we observe in R6/2 mice at 10-weeks of age represents true neuron loss, and not merely loss of ENK expression in otherwise surviving neurons.

In situ Hybridization Histochemistry Studies.

We analyzed tissue from vehicle-treated and MTD LY379268-treated 10-week old R6/2 and WT mice (treated daily since the fourth week of life) that had been fresh-frozen processed for ENK and BDNF mRNA detection by ISSH, using previously described methods (1, 2, 18). ISHH was performed on 20 μm thick fresh-frozen cryostat sections through the PFN. The sections were collected onto pre-cleaned Superfrost®/Plus microscope slides, dried on a slide warmer, and stored at −80°C until used for ISHH. To process sections for ISHH, the slides were removed from −80°C, quickly thawed and dried using a hair dryer. After fixation with 2% paraformaldehyde in saline sodium citrate (2x SSC) for 5 minutes, the sections were acetylated with 0.25% acetic anhydride/0.1M triethanolamine hydrochloride (pH 8.0) for 10 minutes, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and air-dried. Digoxigenin-UTP labeled cRNA probes (i.e. riboprobes) for preproenkephalin (PPE) were transcribed from plasmids with PPE cDNA inserts (817bp in size), generated by us using RT-PCR. Primers for PPE PCR were: Sense: 5’-TTCCTGAGGCTTTGCACC-3’, and Antisense: 5’-TCACTGCTGGAAAAGGGC-3’. Primers for BDNF PCR were: Sense: 5’-GGCGCCCATGAAAGAAGTAAAC-3’, and Antisense: 5’-CGGCAACAAACCACAACATTAT-3’. The PPE riboprobe was directed against nucleotides 312–1128 (GenBank accession number NM_001002927), while the BDNF riboprobe was directed against nucleotides 715–1634 (GenBank accession number MN_007540), which includes the protein coding region of BDNF and part of the adjacent 3-prime untranslated sequence. Note that all BDNF transcripts share this sequence, found within exon IX of the BDNF gene, and thus our probe detected all BDNF transcripts. The sections were incubated with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probe in hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide, 4x SSC, 1x Denhardt’s solution, 200μg/ml denatured salmon sperm DNA, 250μg/ml yeast tRNA, 10% dextran sulfate, and 20mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 63°C overnight. After hybridization, the slices were washed at 58°C consecutively in 4x SSC, 50% formamide with 4x SSC, 50% formamide with 2x SSC, and then 2x SSC, followed by treatment with RNase A (20μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. Finally, sections were washed at 55°C in 1xSSC, 0.5xSSC, 0.25xSSC, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, and air-dried. Digoxigenin labeling was detected using anti-digoxigenin Fab fragments conjugated to alkaline phosphatase, as visualized with nitroblue tetrazolium histochemistry (Roche, Indianapolis, IN).

Analysis of ISHH Labeling.

Blinded counts of BDNF+ perikarya were performed bilaterally on high-resolution images of PFN from one section from each animal, which were captured using a high-resolution Aperio Scanscope XT Scanner. Neuron abundance reported here for BDNF represents the labeled neuron number per mm2 for the mid-level of PFN where it surrounds the fasciculus retroflexus. Relative BDNF message was calculated as the product of the area of PFN containing BDNF-labeled neurons and the mean signal intensity of the PFN area containing BDNF-labeled neurons (as measured by ImageJ). Images were standardized to a common background intensity for these measurements, using fasciculus retroflexus for PFN and external capsule for cerebral cortex. Levene’s test was used to confirm homogeneity of variance. The values for the two sides of the brain for each mouse were averaged. Group results were analyzed by ANOVA using SPSS, with Fisher PLSD used for individual group comparisons. Linear regression was used to assess the relationship between PFN and/or M1 motor cortex layer 5 perikaryal BDNF signal on one hand and striatal ENK+ neuron abundance on the other, using M1 BDNF expression data and ENK+ striatal neuron counts for these same mice from our previously published study on corticostriatal BDNF (2). Missing data was mean filled for 8 mice for which we did not have all three values for the regression analysis, which was also performed using SPSS.

Results

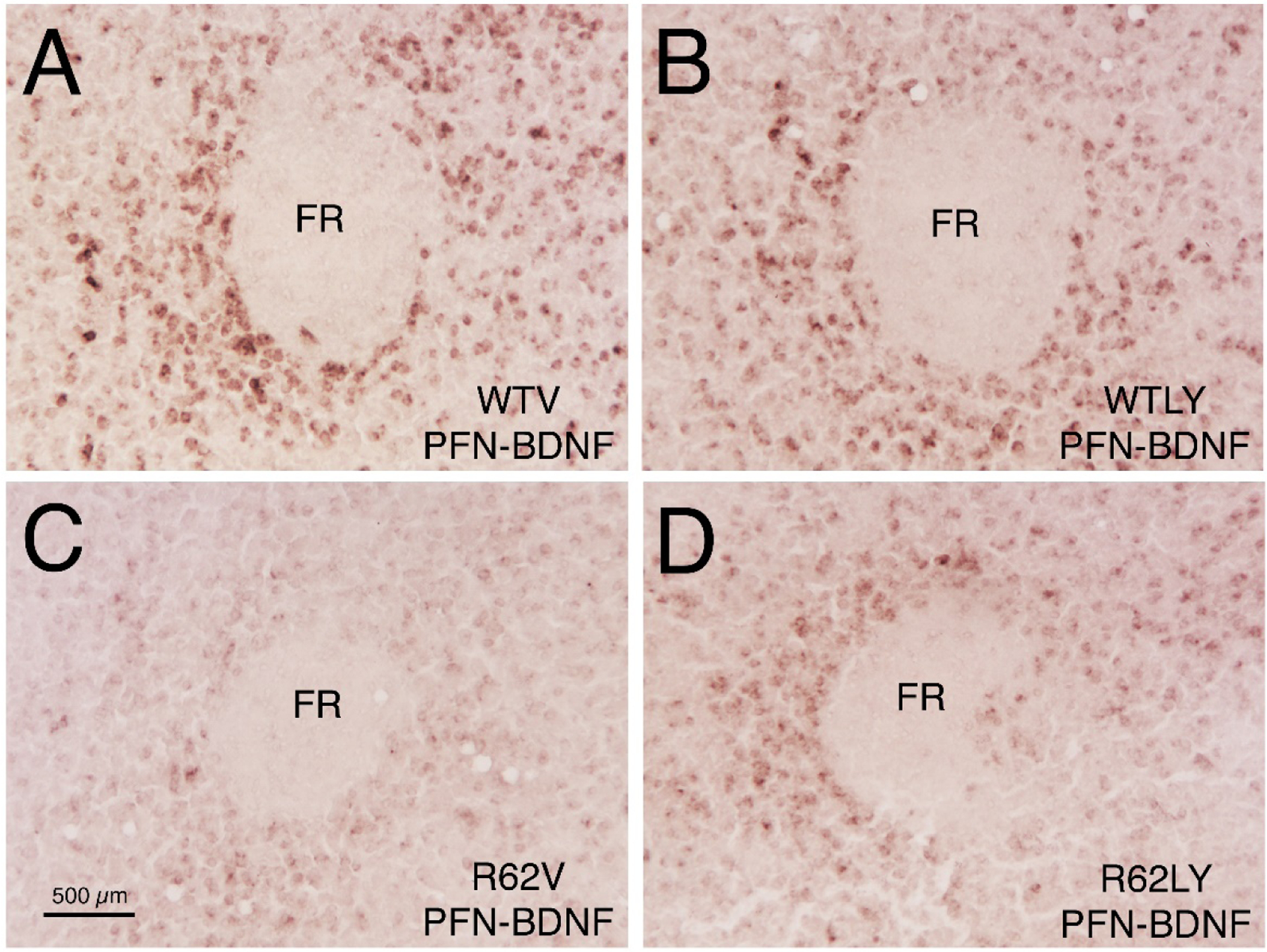

We observed that BDNF expression was prominent in PFN neurons in WT mice, but reduced in vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (Fig. 1). Our measurements revealed that relative perikaryal BDNF message signal magnitude in PFN in vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (n=22) was 64.0% of that in vehicle-treated WT mice (n=21), which was significantly less (p<0.0110) than in the vehicle-treated WT mice. Perikaryal BDNF message in PFN was elevated by daily LY379268 treatment of R6/2 mice (n=23) to 79.6% of vehicle-treated WT mice (Fig. 2), which was no longer significantly different than in vehicle-treated WT mice (p=0.1396), indicating a partial rescue effect of LY379268 treatment. LY379268 treatment did not significantly affect BDNF message in PFN in WT mice (n=22). We did not detect any significant loss in the numbers of BDNF+ neurons in PFN per unit area (i.e. spatial density) in the vehicle-treated R6/2 mice (although their spatial density was lessened by about 10%), nor was the abundance of BDNF+ neurons in PFN per unit area elevated by LY379268 treatment in R6/2 mice (Fig. 2). Thus, LY379268 treatment boosted BDNF message in PFN neurons closer to normal levels, but did not demonstrably affect BDNF+ PFN neuron numbers at 10 weeks of age, which was not significantly reduced per unit area in any case in the R62V mice.

Figure 1.

Images of right parafascicular nucleus (PFN), showing ISHH labeling for BDNF message, in 10-week old WT mice injected sc daily with either vehicle (WTV) or LY379268 (WTLY) compared to 10-week old R6/2 mice injected sc daily with either vehicle (R62V) or LY379268 (R62LY). Note that BDNF message is reduced in the R6/2 mice, and increased by LY379268 in R6/2 mice. Images A-D are to the same scale, and scale bar in C applies to all four. FR = fasciculus retroflexus.

Figure 2.

Effect of LY379268 on BDNF message in the parafascicular nucleus and BDNF+ neuron spatial density (perikaryal per unit area), at 10 weeks of age. Perikaryal BDNF signal level differed between groups, but BDNF+ neuron abundance per unit PFN area did not. In particular, R6/2 mice receiving vehicle (R62V) showed significantly lower BDNF message in PFN than did WT mice receiving either vehicle (WTV) or LY379268 (WTLY) (asterisk), but R6/2 mice treated with LY379268 did not. BDNF neuron spatial density, however, was not significantly reduced in PFN in R6/2 mice. Mice used for PFN BDNF+ neuron counts: 10 WTV, 10 WTLY, 9 R62V, and 9 R62LY. Mice used for BDNF expression in PFN: 21 WTV, 22 WTLY, 22 R62V, and 23 R62LY. The results are shown as bar graphs with individual data point superimposed.

We previously reported that the abundance of enkephalinergic (ENK+) neurons in striatum of vehicle-treated 10-week old R6/2 mice is significantly reduced to about 70% of that in vehicle-treated WT mice, and significantly increased but not fully normalized by daily LY379268 treatment (2). Across the four groups and 53 mice used for this analysis, the abundance of enkephalinergic striatal neurons was highly and significantly correlated (r=0.53415) with the level of M1 cortical layer 5 perikaryal BDNF message (p=0.00038), the latter of which was reduced to 47.1% of WTV in R62V mice (p=0.0001) and restored to 78.9% of WTV in R62LY mice (a significant increase compared to R62V mice, p=0.00367). The PFN perikaryal BDNF signal was also significantly correlated with the abundance of ENK+ striatal neurons (p=0.043473), but the correlation was lesser (r=0.27848) than for M1 layer 5 neurons. Although both correlations are significant, the higher correlation for M1 suggests a greater impact of cortical M1 BDNF message loss on ENK+ striatal neuron loss than of PFN BDNF message loss, in keeping with the greater contribution of cortex to striatal BDNF (6, 14), and the greater cortical than thalamic BDNF loss in R6/2 mice observed here. Nonetheless, using multivariate regression analysis to assess the combined impact of PFN expression and cortical expression of BDNF, we found that together they were more highly (r=0.57166) and significantly (p=0.000051) correlated with enkephalinergic striatal neuron abundance than was either alone. Thus, the BDNF boost by LY379268 for cortex and PFN both appear to contribute to ENK+ striatal neuron survival, although the former more so. Note, however, this interpretation assumes that BDNF production is largely linear with BDNF message.

Discussion

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is produced by cortical and thalamic neurons and transported axonally to their projection targets, including striatum (5, 6, 15), where it promotes the development, differentiation, plasticity and survival of neurons (5, 19, 20). As shown in the present and prior studies, mutant huntingtin reduces cortical and thalamic BDNF expression and protein transport to striatum in HD mice (2, 3, 4, 5, 15). Various lines of evidence indicate this may play a role in striatal pathogenesis and dysfunction in HD, particularly for enkephalinergic indirect pathway striatal projection neurons (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). For example, placing the R6/1 HD transgene on a hemizygous BDNF knock-out background exacerbates striatal ENK+ neuron loss but does not affect the survival of direct pathway substance P-containing (SP+) striatal projection neurons (7). Moreover, cortex-specific BDNF knock-out results in striatal pathology that mimics that in human HD, including the greater ENK+ neuron vulnerability (6, 8), and embryonic deletion of the BDNF receptor (TrkB) from striatal neurons results in a particularly profound reduction in ENK+ striatal neurons (21). Note that the fact that cortex-specific BDNF knock-out does not yield as rapidly a progressive striatal pathology as seen in R6/2 mice (1, 2, 6) indicates that additional mechanisms beyond disrupted delivery of BDNF to striatum by the corticostriatal projection contribute to R6/2 pathogenesis. It may be that diminished thalamostriatal delivery of BDNF is one of these additional factors driving more rapid pathogenesis in R6/2 mice.

The above lines of evidence suggest that boosting striatal BDNF might be therapeutic in HD. Consistent with this conclusion, behavioral performance is improved and disease progression is slowed in transgenic HD mice overexpressing BDNF (9, 11). Similarly, daily intrastriatal administration of BDNF in R6/1 HD mice increases the number of striatal neurons expressing ENK and improves behavior (7), and driving expression of BDNF in striatal astrocytes delays the R6/2 motor phenotype (10, 22). Similarly, striatal BDNF infusion (23) or driving BDNF expression with daily doxycycline (24) mitigates disease in R6/2 mice. Note that the HD mutation also reduces striatal levels of the BDNF receptor TrkB (25, 26), which in principle might render increasing BDNF levels not fully effective in restoring pro-survival BNDF signaling in striatal neurons. Our unpublished qPCR data indicate, however, that the beneficial actions of LY379268 in R6/2 mice also involve increasing striatal TrkB levels, thus mitigating this concern for LY379268 at least. In addition to its action in boosting BDNF signaling in striatum, chronic LY379268 treatment may also be beneficial for striatal neurons in HD by means of its demonstrated anti-excitotoxic actions. Excitotoxicity mediated by corticostriatal release of glutamate, made harmful by either excessive release or excessive postsynaptic activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors, has also been proposed to be involved in HD pathogenesis (27, 28), and may also be among the additional processes that make R6/2 pathogenesis more rapid than seemingly could be achieved by cortical knockout of BDNF expression alone (1, 2, 6). Corticostriatal and thalamostriatal terminals are enriched in mGluR2/3, which are negative coupled to adenylyl cyclase (29) and thereby act as autoreceptors that dampen glutamate release (30, 31, 32). An mGluR2/3 agonist such as LY379268 reduces glutamate release and thereby reduces activation of extrasynaptic NMDA-type glutamate receptors, which are thought to underlie excitotoxic injury to striatal neurons in HD (27, 33). In our prior study, we showed that SP+ striatal neurons in R6/2 mice do not show an evident BDNF dependence in WT mice or R6/2 mice at 10-weeks of age (2), suggesting that their eventual loss in HD (34, 35) is not driven notably by BDNF deprivation. It may be their loss is driven more by excitotoxicity, potentially explaining why the two main striatal projection neuron types show differential vulnerability in HD – they are largely injured by different pathogenic processes. In any case, as mGluR2/3 agonists such as LY379268 are apparently neuroprotective by both their BDNF boosting effects and their anti-excitotoxic actions (32), they may effectively protect both projection neuron types over the course of disease. The means by which both acute and chronic LY379268 increases BDNF production by corticostriatal and thalamostriatal neurons (2, 36) is uncertain, but activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors on BDNF-producing cortical neurons is known to inhibit their BDNF expression (37). Thus, increased extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activation among cortical and thalamic neurons in HD brain may hinder their BDNF production, and attenuation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signaling by mGluR2/3 agonists such as LY379268 may thus reverse this.

Our prior study showing that daily LY379268 treatment boosts BDNF message in corticostriatal neurons and in R6/2 striatum (2) and the present evidence that daily LY379268 treatment also boosts BDNF message in PFN thalamostriatal neurons and contributes to neuroprotection of striatal enkephalinergic neurons is of interest with regard to therapeutic approaches for HD, given our findings that daily LY379268 treatment also ameliorates other HD-like neuropathology and motor deficits in R6/2 mice, and may also have a neuroprotective anti-excitotoxic action (1, 2). Although a variety of approaches have been tested and shown efficacy in reducing symptoms in mutant HD mice (38, 39), therapies that have been subsequently tested in human clinical trials have not had success in slowing HD in human patients. For example, although inhibition of phosphodiesterase 10A (PDE10A) with the compounds PF-04898798 or PF-02545920 was reported to reduce HD symptoms in mouse models (40), a clinical trial with PF-02545920 in HD patients failed to show efficacy (41). Similarly, knockdown of mutant (and wild-type) huntingtin expression by delivery into the nervous system of antisense oligonucleotides against huntingtin message was extensively and successfully tested in animal models (42), but nonetheless intrathecal delivery in human clinical trials of some of these same constructs proved ineffective (43). The encouraging results we have obtained here and in our prior studies (1,2) with the mGluR2/3 agonist LY379268 in abating motor deficits and reversing brain abnormalities in R6/2 mice, a highly aggressive model of HD, and in combating the presumed underlying pathogenic mechanisms, suggests that perhaps this class of drug should be given more consideration as a straightforward pharmacological approach for slowing HD progression. In this regard, it would be useful to test mGluR2/3 agonist benefit in additional animal models that more precisely mimic human HD genetically.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aminah Henderson, Marion Joni, and Ting Wong for histological assistance, and Michael Piantedosi and Trevon Clark for assistance with behavioral studies and mouse colony maintenance.

Funding

Supported by the CHDIF (AR), and NIH NS28721 (AR). The authors have no financial interest in the research reported here.

Abbreviations:

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- ENK

enkephalin

- FR

fasciculus retroflexus

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- ISHH

in situ hybridization histochemistry

- GluR2

metabotropic glutamate receptor 2

- mGluR3

metabotropic glutamate receptor 3

- mGluR2/3

type II metabotropic glutamate receptors

- MTD

maximum tolerated dose

- PFN

parafascicular nucleus

- R62V

Vehicle-treated R6/2 mice

- R62LY

LY379268-treated R6/2 mice

- sc

subcutaneous

- SNc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- SP

substance P

- TrkB

BDNF receptor

- WT

wild-type

- WTV

vehicle-treated WT mice

- WTLY

LY379268-treated WT mice

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Reiner A, Lafferty DC, Wang HB, Del Mar N, Deng YP, The group 2 metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist LY379268 rescues neuronal, neurochemical and motor abnormalities in R6/2 Huntington’s disease mice, Neurobiol. Disease 47 (2012a) 75–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiner A, Wang HB, Del Mar N, Sakata K, Yoo W, Deng YP, BDNF may play a differential role in the protective effect of the mGluR2/3 agonist LY379268 on striatal projection neurons in R6/2 Huntington’s disease mice, Brain Res 1473 (2012b) 161–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zuccato C, Ciammola A, Rigamonti D, Leavitt BR, Goffredo D, Conti L, MacDonald ME, Friedlander RM, Silani V, Hayden MR, Timmusk T, Sipione S, Cattaneo E, Loss of huntingtin-mediated BDNF gene transcription in Huntington’s disease, Science 293 (2001) 493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zuccato C, Marullo M, Conforti P, McDonald ME, Tartari M, Cattaneo E, Systematic assessment of BDNF and its receptor levels in human cortices affected by Huntington’s disease, Brain Path. 18 (2008) 225–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuccato C, Cattaneo E, Huntington’s disease, Handbook Experimental Pharmacol. 220 (2014) 357–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baquet ZC, Gorski JA, Jones KR, Early striatal dendrite deficits followed by neuron loss with advanced age in the absence of anterograde cortical brain-derived neurotrophic factor, J. Neurosci 24 (2004) 4250–4258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canals JM, Pineda JR., Torres-Peraza JF, Bosch M, Martın-Ibanez R, Munoz MT, Mengod G, Ernfors P, Alberch J, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates the onset and severity of motor dysfunction associated with enkephalinergic neuronal degeneration in Huntington’s disease, J. Neurosci 24 (2004) 7727–7739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strand AD, Baquet ZC, Aragaki AK, Holmans P, Yang L, Cleren C, Beal MF, Jones L, Kooperberg C, Olson JM, Jones KR, Expression profiling of Huntington’s disease models suggests that brain-derived neurotrophic factor depletion plays a major role in striatal degeneration, J. Neurosci 27 (2007) 11758–11768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gharami K, Xie Y, An JJ, Tonegawa S, Xu B, BDNF overexpression in the forebrain ameliorates huntington’s disease phenotypes in mice, J. Neurochem 105, (2008) 369–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giralt A, Carretón O, Lao-Peregrin C, Martín ED, Alberch J, Conditional BDNF release under pathological conditions E.D., improves Huntington’s disease pathology by delaying neuronal dysfunction, Molec. Neurodegen 6 (2011) 71–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie Y, Hayden MR, Xu B, BDNF Overexpression in the forebrain rescues Huntington’s disease phenotypes in YAC128 mice, J. Neurosci 30 (2010) 14708–14718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng Y, Wong T, Bricker-Anthony C, Deng B, Reiner A, Loss of corticostriatal and thalamostriatal synaptic terminals precedes striatal projection neuron pathology in heterozygous Q140 Huntington’s disease mice, Neurobiol. Dis 60 (2013) 89–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei W, Deng Y, Liu B, Mu S, Guley NM, Wong T, Reiner A, Confocal laser scanning microscopy and ultrastructural study of VGLUT2 thalamic input to striatal projection neurons in rats, J. Comp. Neurol 521 (2013) 1354–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altar CA, Ning CA, Bliven T, Juhasz M, Conner M, Acheson AL, Lindsay RM, Wiegand SJ, Anterograde transport of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its role in the brain, Nature 389 (1997) 856–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samadi P, Boutet A, Rymar VV, Rawal K, Maheux J, Kvann JC, Tomaszewski M, Beaubien F, Cloutier JF, Levesque D, Sadiko AF, Relationship between BDNF expression in major striatal afferents, striatum morphology and motor behavior in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease, Genes Brain Behav 12 (2013) 108–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reiner A., Y. Deng, Disrupted striatal inputs and outputs in Huntington’s disease, CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 24 (2018) 250–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen Brain Atlas, http,//mouse.brain-map.org/welcome.do

- 18.Deng Y, Wang H, Joni M, Sekhri R, Reiner A, Progression of basal ganglia pathology in heterozygous Q175 knock-in Huntington’s disease mice, J. Comp. Neurol 529 (2021) 1327–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lessmann V, Gottmann K, Malcangio M, Neurotrophin secretion: current facts and future prospects, Prog. Neurobiol 69 (2003) 341–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poo MM, Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 2 (2001) 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baydyuk M, Russell T, Liao GY, Zang K, An JJ, Reichardt LF, Xu B, TrkB receptor controls striatal formation by regulating the number of newborn striatal neurons, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108 (2011) 1669–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arregui L, Benítez JA, Razgado LF, Vergara P, Segovia J, Adenoviral astrocyte-specific expression of BDNF in the striata of mice transgenic for Huntington’s disease delays the onset of the motor phenotype, Cell. Mol. Neurobiol 31 (2011) 1229–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giampà C, Montagna E, Dato C, Melone MA, Bernardi G, Fusco FR, Systemic delivery of recombinant brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s Disease. PLoS One 8 (2013) e64037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paldino E, Balducci C, La Vitola P, Artioli L, D’Angelo V, Giampà C, Artuso V, Forloni G, Fusco FR, Neuroprotective effects of doxycycline in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol 57 (2020) 1889–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ginés S, Bosch M, Marco S, Gavaldà N, Díaz-Hernández M, Lucas JJ, Canals JM, Alberch J, Reduced expression of the TrkB receptor in Huntington’s disease mouse models and in human brain, Europ. J. Neurosci 23 (2006) 649–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen KQ, Rymar VV, Sadikot AF, Impaired TrkB signaling underlies reduced BDNF-mediated trophic support of striatal neurons in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s Disease. Front. Cellular Neurosci 10 (2016) 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raymond LA, André VM, Cepeda C, Gladding CM, Milnerwood AJ, Levine MS, 2011.Pathophysiology of Huntington’s disease: time-dependent alterations in synaptic and receptor function, Neuroscience 198 (2011) 252–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeron MM, Hansson O, Chen N, Wellington CL, Leavitt BR, Brundin P, Hayden MR, Raymond LA, Increased sensitivity to N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-mediated excitotoxicity in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease, Neuron 33 (2002) 849–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoepp DD, Jane DE, Monn JA, Pharmacological agents acting at subtypes of metabotropic glutamate receptors, Neuropharmacol 38 (1999) 1431–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Battaglia G, Monn JA, Schoepp DD, In vivo inhibition of veratridine-evoked release of striatal excitatory amino acids by the group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist LY354740, Neurosci. Lett 229 (1997) 161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovinger DM, McCool BA, Metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated presynaptic depression at corticostriatal synapses involves mGLuR2 or 3, J. Neurophys. 73 (1995) 1076–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kingston AE, O’Neill MJ, Lam A, Bales KR, Monn JA, Schoepp DD, Neuroprotection by metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists: LY2354740, LY379268 and LY389795, Europ. J. Pharmacol 377, (1990) 155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milnerwood AJ, Gladding CM, Pouladi MA, Kaufman AM, Hines RM, Boyd JD, Ko RWY, Vasuta OC, Graham RK, Hayden MR, Murphy TH, Raymond LA, Early Increase in extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signaling and expression contributes to phenotype onset in Huntington’s disease mice, Neuron 65 (2010) 178–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng YP, Penney JB, Young AB, Albin RL, Anderson KD, Reiner A, Differential loss of striatal projection neurons in Huntington’s disease: A quantitative immunohistochemical study, J. Chem. Neuroanat 27 (2004) 143–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiner A, Deng YP, Disrupted striatal inputs and outputs in Huntington’s disease, CNS Neurosci. Ther 24: (2018) 250–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Liberto V, Bonomo A, Frinchi M, Belluardo N, Mudo G, Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor activation by agonist LY379268 treatment increases the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor in the mouse brain, Neuroscience 165 (2010) 863–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanhoutte P, Bading H, Opposing roles of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in neuronal calcium signalling and BDNF gene regulation, Current Opinion Neurobiol 13 (2003) 366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh R, Tabrizi SJ, Gene suppression approaches to neurodegeneration, Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 9 (2017) 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramaswamy S, Kordower JH, Gene therapy for Huntington’s disease, Neurobiol. Disease 48 (2012) 243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beaumont V, Zhong S, Lin H, Xu W, Bradaia A, Steidl E, Gleyzes M, Wadel K, Buisson B, Padovan-Neto FE, Chakroborty S, Ward KM, Harms JF, Beltran J, Kwan M, Ghavami A, Häggkvist J, Tóth M, Halldin C, Varrone A, Schaab C, Dybowski JN, Elschenbroich S, Lehtimäki K, Heikkinen T, Park L, Rosinski J, Mrzljak L, Lavery D, West AR, Schmidt CJ, Zaleska MM, Munoz-Sanjuan I, Phosphodiesterase 10A inhibition improves cortico-basal ganglia function in Huntington’s Disease models, Neuron 92 (2016) 1220–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigues FB, Wild EJ, 2017.Clinical Trials Corner: September 2017, J. Huntingtons Disease 6 (2017) 255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson CD, Davidson BL, Huntington’s disease: progress toward effective disease-modifying treatments and a cure, Hum. Mol. Genet 9 (R1), R98–R102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwon D, Genetic therapies for Huntington’s disease fail in clinical trials, Nature 593 (2021) 180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]