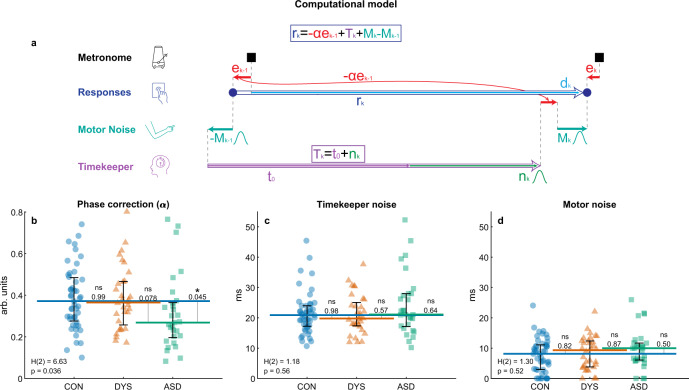

Fig. 3. Trial-by-trial computational modeling of isochronous tapping: Parameters estimated for each participant show that individuals with autism have reduced error correction and intact timekeeper and motor noise.

a Schematic illustration of the computational model used to dissociate error correction mechanisms from poor timekeeping or motor noise29,31,32. Each tapping interval (blue empty arrow) is assumed to be the summation of three mechanisms: (1) error correction based on the previous asynchrony (marked in red, the magnitude of the correction is determined by the phase correction parameter α) (2) timekeeping of the base tempo (composed of a fixed , purple, plus the noise at tap k, , green), and (3) motor noise (turquoise). See also notations in Fig. 1a. Fitting was performed using the bGLS (bounded General Least Squares) estimation method28. b Error correction of phase difference—the fraction corrected (α) is significantly smaller in the ASD group. c Noise in keeping the metronome period, and d Motor noise do not differ between the groups. b–d Each block was modeled separately, and parameters were averaged over the two assessment blocks. The median of each group is denoted as a line of the same color; error bars around this median denote an interquartile range. Kruskal–Wallis H-statistic and corresponding p value are in the bottom-left corner; p values of comparisons between groups are next to the line connecting the groups’ medians. CON control (neurotypical), DYS dyslexia, ASD autism. N = 108 subjects (NCON = 47, NDYS = 32, NASD = 29), one ASD participant was excluded due to a large number of missing taps (see Methods). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.