Graphical abstract

Keywords: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Antimicrobial peptides, Truncated derivatives, PeptideCutter tool, Antibacterial effect, Toxicity, Salt- and serum-resistance

Highlights

-

•

A novel host-defence peptide GV30 was identified from the frog skin secretion of Hylarana guentheri.

-

•

Seven short AMPs were generated by in silico enzymatic digest of GV30 using an online proteomic bioinformatic tool PeptideCutter in ExPASy server.

-

•

Two truncated products, GV23 and GV21, exhibited an improved antibacterial effect against MRSA in vitro and demonstrated a faster bactericidal effect than the parent peptide.

-

•

GV 21 was found to have a better in vivo anti-MRSA activity and retain the good antibacterial activity under salt and serum conditions, along with lower toxicity.

Abstract

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) causing serious hospital-acquired infections and skin infections has become a “superbug” in clinical treatment. Although the clinical treatment of MRSA is continuously improving, due to its unceasing global spread, MRSA has produced much heated discussion and focused study, therefore suggesting an urgent task to find new antibacterial drugs to combat this issue. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are used as the last-resort drugs for treating multidrug-resistant bacterial infections, but their utilisation is still limited due to their low stability and often strong toxicity.

Here, we evaluated the structure and the bioactivity of an AMP, GV30, derived from the frog skin secretions of Hylarana guentheri, and designed seven truncated derivatives based on the presence of cleavage sites for trypsin using an online proteomic bioinformatic resource PeptideCutter tool. We investigated the anti-MRSA effect, toxicity and salt- and serum-resistance of these peptides. Interestingly, the structure–activity relationship revealed that removing “Rana box” loop could significantly improve the bactericidal speed on MRSA. Among these derivatives, GV21 (GVIFNALKGVAKTVAAQLLKK-NH2), because of its faster antibacterial effect, lower toxicity, and retains the good antibacterial activity and stability of the parent peptide, is considered to become a new potential antibacterial candidate against MRSA.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the global scaling up development of multidrug-resistant bacteria has become an important factor threatening human health [1], [2]. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a microorganism causing genuine skin and flimsy tissues diseases [3]. Moreover, MRSA is a classic reason for nosocomial infections, which can cause a variety of diseases such as abscesses, endocarditis, sepsis and pneumonia [4], [5], [6]. Likewise, these strains could adhere to the surface of medical devices to form biofilms, resulting in biofilm-related complications and irreversible damage to medical devices [7]. Previous research indicated that more than 25% of nosocomial infections are associated with the formation of biofilms [8]. Most notably, MRSA has gradually developed drug resistance to most clinically approved antibiotics (including vancomycin) [9]. One of the solutions to these problems is to find a new drug that is different from the traditional single-target antibiotics, so as to break down the threat of MRSA to human health [10].

Recent research has reported that many short peptides have been found to exist in Nature. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), also named host defence peptides, are a widespread and heterogenous group of molecules generated by many tissues in various invertebrates, plants, and animals [11]. AMPs are an optimal choice to address resistance mainly because of their strong membrane permeabilisation effects and multiple targets in the antibacterial process [12]. Since the first AMP was found in 1970, more than 2800 AMPs have been discovered, according to the antimicrobial peptide database (APD) (http://aps.unmc.edu/AP/main.php), and this number is still increasing [13]. To date, hundreds of AMPs have been characterised with respect to amino acid compositions and associated biological activities. So far, some amphibian AMPs were reported to have inhibitory effects on MRSA (e.g., ranatuerin-2PLx) [14], suggesting amphibian skin secretion is a promising resource for fighting drug-resistant bacteria. Although AMPs have many biological effects, due to their high toxicity, high manufacturing costs and poor stability, it has been difficult for AMPs to be seriously considered as candidates for clinical drugs [15].

Since the first brevinin-2 peptide was extracted from the skin secretion of the frog, Rana brevipoda porsa, in 1992, the brevinin-2 family has gradually entered the researcher's field of vision [16]. The brevinin-2 family has noticeable inter-species and intra-species structural differences [17]. Unlike other families with obvious conserved sequences, the brevinin-2 family has four conserved amino acids (Lys15, Cys27, Lys28 and Cys33) [18]. In recent years, studies on the brevinin-2 family have shown that its member peptides exhibited multiple biological effects such as antibacterial [19], [20], anticancer [21], [22], anti-inflammatory [23], and insulin-releasing [24] etc.

Poor stability of many peptides against peptidases/proteases has been one of the main obstacles preventing them from entering the oral drug market [25]. Therefore, it would be essential to increase the stability of peptides to hydrolytic enzymes through drug design methods. Several methods have been developed through repeated attempts by researchers to circumvent the enzymatic hydrolysis of peptide drugs [26], [27], [28]. For example, for exopeptidases that cleave terminal amino acids, modification of terminal amino acids with amino and carboxyl groups (called end-capping) is generally adopted [29]. For endopeptidases, methods of methylation of amide nitrogen atoms have been used to prevent the degradation of drugs [30]. Similarly, studies have found that truncating peptides is also a reliable method to increase the stability of peptide drugs [31]. The main hydrolytic enzyme in the human intestine, trypsin, can decompose small-molecule cationic AMPs at a fast rate [32]. Since the cleavage site of trypsin is located at the C-terminal sides of Lys and Arg residues [33], the number of positively-charged residues in peptide drugs is critical to their stability against trypsin. Some studies indicated that shortening the length of peptide drugs is a good way to increase stability because trypsin always preferentially selects a certain substrate length for the reaction [34]. However, some scholars have pointed out that when the number of amino acids is too small, peptides can also be hydrolysed by trypsin [35], so it is crucial to find the proper number of net charges and the proper length of the peptide sequence.

In this study, we discovered an AMP, GV30, in the skin secretions of the frog (Hylarana guentheri). After solid-phase synthesis and purification, we evaluated the structure and biological activity of GV30. Then we truncated GV30 to obtain seven derivatives by predicting the possible products which may be produced in the trypsin enzymatic process. Their antibacterial activity (especially against MRSA), toxicity and possible mechanism of action were analysed. On the one hand, we had hoped to explore the vital amino acids and/or structures to study its structure–function relationships. On the other hand, we expected to obtain a peptide with the potential to become a drug candidate, which could maintain the antibacterial effect of the parent peptide, accelerate antibacterial kinetics, permit truncation of the sequence, reduce toxicity and improve stability.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Harvesting of skin secretion from Hylarana guentheri

Adult frogs (Hylarana guentheri) were captured from different locations in Fujian Province, People’s Republic of China. After secretion harvesting, the frogs were released back into the wild. The skin secretion was procured through gentle electrical stimulation (5 V 100 Hz.140 ms pulse width) by moving a bipolar electrode around the skin surface of the frog (C.F. palmer, UK) until a white secretion was obvious. The secretion was collected by washing the skin surface with deionised water and collection into a chilled glass beaker, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilisation in a 1–2/LD freeze dryer (Alpha, Germany).

2.2. Molecular cloning

Firstly, 5 mg of lyophilised skin secretion from Hylarana guentheri were dissolved in 1 ml of lysis/binding buffer and transferred into a microcentrifuge tube containing the prepared Dynabeads (Dynal Biotech, UK). Then, the beads bonded to the polyA-RNA were treated with TrisHCL and heated at 80℃ for 2 min to collect the mRNA. A cDNA library was constructed using a Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT™ Kit (Dynal Biotech, UK) to obtain a full-length precursor encoding cDNA sequence. A 3′-CDS primer was used in the reverse transcription process to construct a 3′-RACE cDNA library. A SMART II primer and a 5′-CDS primer were then used in building a 5′-RACE cDNA library. The 3′-RACE PCR was performed by using a sense primer (50-TAYGARATHGAYAAYMGICC-30 Y = C + T, R = A + G, H = A + T + C, M = A + C) and a Nested Universal Primer (NUP) with the following PCR programme: 1 min for initial denaturation at 94 ℃; 40 cycles for further denaturation (94 ℃, 30 s), primer annealing (59 ℃, 30 s) and extension (72 ℃, 3 min), finally, a further 10 min for final extension at 72 ℃. The PCR product was analysed by gel electrophoresis and purified by a Hi-Bind® DNA Mini Column (Omega bio-tek, USA). The ligation process was carried out by utilising a pGEM t Easy Vector system (Promega, USA). The vector with the foreign gene was cloned in JM109 high-efficiency competent cells (Promega, USA). The DNA product was analysed and purified as described before. The DNA sequencing reaction was performed by use of a BigDye Terminator sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, USA), and the DNA product was analysed by an automated ABI 3100 DNA sequencer.

2.3. Bioinformatic analysis

Through bioinformatic research on the cDNA sequences from molecular cloning, the sequence information and structural parameters of the peptide were obtained. The BLAST database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) was used to translate the encoding cDNA sequence to obtain the peptide sequence. The online tool, UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/), was used to obtain the basic bioinformatics of this peptide.

2.4. Peptide design and secondary structure modelling

An online proteomic bioinformatic resource ExPASy (https://www.expasy.org/) was used to help design the derivatives of GV30. The sequence of the peptide was imported to the PeptideCutter online tool from the ExPASy server to predict the trypsin enzymatic products. The parent peptide was first cleaved at the “Rana box” and amidated at the C-terminus to obtain GV23. Then, the peptide was cleaved from the C-terminus based on the bioinformatic prediction to obtain GV21, GV20, GV12 and GV8. Subsequently, according to the antibacterial effect, the non-biologically active GV12 sequence was cut from GV30 and GV23 to obtain GV18 and GV11, respectively. The three-dimensional structure prediction was conducted by the PEPFOLD-3 (https://bioserv.rpbs.univ-paris-diderot.fr/services/PEP-FOLD3/) programme, the designed truncated peptide sequences were imported into the PEPFOLD-3 server, and the selected three-dimensional models of the peptides were used for the secondary structure analysis.

2.5. Solid-phase peptide synthesis

GV30 and its derivatives were synthesised by using a Tribute Peptide Synthesiser (Protein Technologies, USA). The amino acids and the activator, HBTU (2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate), were weighted in vials. After coupling, the cleavage solution (94 % trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) + 2 % triisopropylsilane(TIS) + 2 % 1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT) + 2 % H2O) was prepared to perform the cleavage reaction of the protection groups. Then, ice-cold diethyl ether was prepared to wash the peptide, and the washed peptide was then dissolved in buffer A solution (TFA /water (0.05/99.95, v/v)). Finally, 0.3 % H2O2 was prepared as an oxidising agent to form disulphide bonds.

2.6. Purification and characterisation of GV30 and its designed analogues

The crude peptide was first purified utilising reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC). The RP-HPLC was performed utilising a Cecil Adept CE4200 HPLC system (Amersham Biosciences, UK), a Jupiter C-5 semi-preparative column (25 × 1 cm, Phenomenex, UK) and Powerstream HPLC software. The molecular masses of the purified peptides were obtained and confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (10 mg/ml) was used as matrix solution). The MALDI plate was sent to the mass spectrometer (Voyager DE, PerSeptive Biosystems, USA), and the masses observed were compared with the theoretical mass values of peptides (The mass spectra of all purified peptides were supplementary in Fig. S1).

2.7. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)/minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) determination

Six different bacteria and three MRSA strains were tested in this experiment to detect the antimicrobial effect of GV30 and its derivatives, including Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (NCTC 10788), MRSA (NCTC 12493), Escherichia coli (E. coli) (ATCC 8739), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) (ATCC 43816), Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium) (NTCC-12697), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) (ATCC 9027), MRSA (BO38 V1S1 A), MRSA (BO42 V2E1 A) and MRSA (ATCC-BAA 1707). The tested bacteria were cultured in Mueller Hinton Broth medium (MHB) with norfloxacin (20 mg/l) as a positive control. All bacteria were incubated at 37 °C overnight and diluted to 5 × 105 CFU/ml before treating with peptides. The peptides were diluted with PBS to 51200 µM and further double-diluted to 100 µM. One microlitre of each peptide concentration was mixed with 99 µl of bacterial suspensions in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C for 20 h. After culturing, the 96-well plate was analysed using a Synergy HT plate reader (BioliseBioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) set to detect at 550 nm. The concentration at which no apparent bacterial growth was present in the 96-well plate was regarded as the MIC. Starting with the MIC value, 10 µl of the solution were removed from each well, and drops were placed onto Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) plates. The plates were cultured at 37 °C for 20 h. After culturing, the lowest concentration with no colony growth was regarded as the MBC.

2.8. Anti-biofilm assays

To measure the anti-biofilm activity of GV30 and its derivatives, five types of bacteria (S. aureus (NCTC 10788), MRSA (NCTC 12493), MRSA (BO38 V1S1 A), MRSA (BO42 V2E1 A) and MRSA (ATCC-BAA 1707) were used. Tryptic soy broth (TSB) culture medium was used to culture the bacteria. The biofilm in this assay was detected by crystal violet staining. Firstly 100 μl of 5 × 105 CFU/ml bacteria were added to 1 μl of each different concentration of peptide (two-fold from 51200 μM to 100 μM) for 24 h at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm, and after forming the biofilm, 100 μl of PBS was used to rinse the biofilm twice. Then 100 μl of methanol were added and dried to fix the biofilm, followed by 100 μl of 0.1% crystal violet to stain for 15 min. Excess crystal violet was further rinsed off by PBS. After drying, 30% glacial acetic acid was added to each well of the plate. The plate was shaken for 15 min before detecting the well OD values at 595 nm using a Synergy HT plate reader. The MBIC (the minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration) value referred to the minimum concentration in which the biofilm inhibitory rate was more than 90%. Unlike measuring the MBIC value, to determine the MBEC (the minimum biofilm eradication concentration) value, 100 μl of the bacteria were first added into 96-well plates. After the biofilm had formed, it was rinsed with PBS twice to remove the planktonic cells, and then, different concentrations of the peptides were added (same as in the MBIC assay) and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm for 24 h. After this, the mass of biofilm was measured in the same way as the MBIC value, and the minimum concentration in which the eradication rate was greater than 99.9% was considered to be the MBEC value [36].

2.9. Anti-persister cells assay

The biofilm was formed and obtained by the same method as in the anti-biofilm assay described in 2.8. After biofilm formation, a high concentration of antibiotic (4 μg/ml vancomycin) was prepared to treat the biofilm for 24 h, followed by a washing step twice with PBS. Then, different concentrations of peptides were added to each well and incubated for 24 h. The minimum anti-persister cells eradication concentration was determined by the same method as in the anti-biofilm assay described in 2.8 [37].

2.10. Time-killing assay

To evaluate the antimicrobial kinetics of different peptides, the time-killing assay was performed using the Gram-positive bacterium, MRSA (NCTC 12493). MRSA was incubated with different concentrations (1 × MIC, 2 × MIC) of different peptides. At different time points (0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120 and 180 min.), the mixtures of peptides and bacteria were spotted onto the MHA plates. The bacterial colonies were counted and recorded after overnight incubation.

2.11. Determination of in vivo antimicrobial activity of peptides

The assessment of in vivo antimicrobial activity of GV30 and its derivatives was performed using the larvae of Galleria mellonella [38]. The infection model was constructed by injecting 10 μl of MRSA (NCTC 12493) bacterial suspension (1 × 107 CFU/ml) prepared in PBS. After one hour, each infected larva was further administered an injection of 10 μl of peptide solution at different concentrations of 6.25 mg/kg, 12.5 mg/kg and 25 mg/kg. The infected larvae administered 10 μl of PBS were regarded as a negative control, while 50 mg/kg of vancomycin was used as a positive control. Each group contained ten larvae, and all larvae were observed every 12 h for five days.

2.12. SYTOX green permeability assay

To determine the permeability of treated MRSA, the bacteria were cultured in TSB medium to log phase then centrifuged at 4 °C at 1000 × g for 10 min. The bacteria at the bottom of the tube were then collected and washed with 5% TSB/0.85% NaCl solution twice. Then the bacteria were diluted to reach an OD value of 0.7 at 580 nm. Then 40 μl of the bacteria, 10 μl of the SYTOX green (50 µM, Life Technologies, UK) and 50 μl peptide solution were added to each well of the black 96-well plate. The plate was analysed at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 528 nm at 37 °C for 120 min (interval 5 min), using the Synergy HT plate reader.

2.13. Haemolysis assay

The debris and impurities of the erythrocytes were washed with PBS in advance of making a 2 % v/v erythrocyte suspension, and the peptide concentrations were prepared from 512 µM to 2 µM in PBS [38]. Peptides and the erythrocyte suspension were mixed and cultured at 37 °C for 2 h and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was prepared as a positive control, and PBS was prepared as a negative control. After incubation, the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate and then analysed using a Synergy HT plate reader at 570 nm.

2.14. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity assay

A Pierce LDH cytotoxicity assay kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used for the LDH assay. The human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT was used in this assay. Eight-thousand cells were plated into each well of the 96-well tissue culture plate with 100 µl of medium and incubated at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 overnight. Cells were cultured with different peptide concentrations from 100 µM to 1 µM for 24 h. Ten microlitres of lysis buffer was prepared as the maximum LDH activity control. After incubating at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 45 min, 50 µl of samples were transferred to each well of a 96-well flat-bottom plate. Then, 50 µl of the reaction mixture was transferred to the wells and mixed. The 96-well plate was cultured for 30 min while protected from light at room temperature. Then, 50 µl of supplied stop solution were added to each well and mixed. The plate was sent to the plate reader and analysed at 490 nm and 680 nm.

2.15. Condition sensitivity assays

The assessment of the condition sensitivity of the peptides was performed in a MIC assay under salt and serum conditions. MRSA (NCTC 12493) was selected as the test bacterium [39]. Different concentrations of salts (150 mM NaCl, 4.5 mM KCl, 6 μM NH4Cl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 8 mM ZnCl2, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 4 mM FeCl3 and 10% horse serum (Gibco, New Zealand)) were added to the MHB to examine the effects of each salt and serum on the antimicrobial activities of the peptides.

2.16. Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed using Prism software (Version 6.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The error bars in the graphs around mean data points indicated the standard error of the mean (SEM) for each set of data in the nine replicates from three experiments.

3. Results

3.1. The discovery and identification of GV30

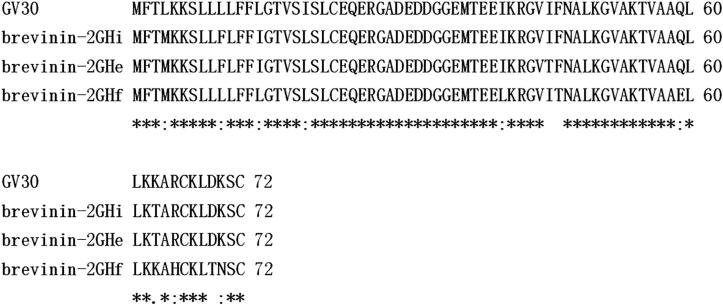

The nucleotide sequence of the novel AMP, GV30, was acquired by “shotgun” cloning of encoding mRNA from Hylarana guentheri skin secretion, and the peptide sequence was translated using the BLAST database (Fig. 1). The sequence had been deposited in the GenBank with the accession number: MZ272437. Through BLAST analysis, the peptide precursor showed a high degree of similarity with members of the brevinin-2 family (brevinin-2GHi, brevinin-2GHe and brevinin-2GHf from Sylvirana guentheri) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Nucleotide and translated peptide sequence of the novel peptide GV30 from the skin secretion of Hylarana guentheri. The signal peptide sequence is double-underlined, the mature peptide sequence is single-underlined, and the stop codon is represented by an asterisk.

Fig. 2.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of GV30 and some other brevinin-2 peptides. The peptide names are shown before the sequences. The asterisks represent identical amino acids in corresponding positions.

3.2. Generation of short AMPs from the parent peptide GV30

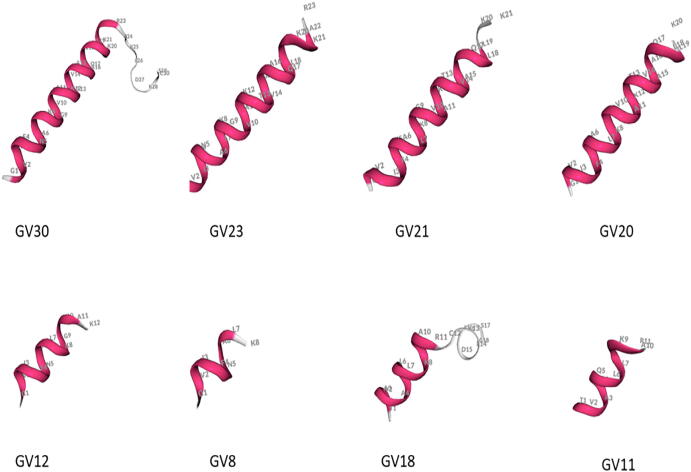

In order to maintain the biological activity of the parent peptide, shorten its length, improve salt- and serum- resistance and reduce toxicity, the GV30 sequence was truncated by firstly removing the “Rana box” from the C-terminus at a cleavage site of trypsin (Fig. 3), then in turn, producing the truncated analogues, GV23, GV21, GV20, GV12, and finally GV8, all at further trypsin cleavage sites. Then, since GV12 did not have antibacterial activity, its sequence was deleted from GV30 and GV23 sequences to obtain GV18 and GV11, respectively.

Fig. 3.

The trypsin cleavage site prediction of GV30. The prediction was performed by an online tool Expasy PeptideCutter.

By analysing the physicochemical properties of GV30 and its analogues/fragments (Table 1), it was found that by continuous shortening of the sequence of the first five peptides, the number of charged amino acids continuously decreased. Among these, GV18 contained the lowest net charge (only one positively charged amino acid), while GV18 and GV11 retained five and four net charges, respectively. In terms of hydrophobicity, GV8 had the highest hydrophobicity, reaching 0.653, while GV11 had the lowest hydrophobicity.

Table 1.

The physicochemical properties of GV30 and its analogues.

| Peptide name | Sequence | Net charge | Hydrophobicity <H> |

|---|---|---|---|

| GV30 | GVIFNALKGVAKTVAAQLLKKARCKLDKSC | +7 | 0.345 |

| GV23 | GVIFNALKGVAKTVAAQLLKKAR –NH2 | +6 | 0.364 |

| GV21 | GVIFNALKGVAKTVAAQLLKK –NH2 | +5 | 0.432 |

| GV20 | GVIFNALKGVAKTVAAQLLK –NH2 | +4 | 0.503 |

| GV12 | GVIFNALKGVAK-NH2 | +3 | 0.481 |

| GV8 | GVIFNALK-NH2 | +2 | 0.653 |

| GV18 | TVAAQLLKKARCKLDKSC | +5 | 0.255 |

| GV11 | TVAAQLLKKAR –NH2 | +4 | 0.236 |

Previous studies had shown that the “Rana box” is a representative conserved sequence of the brevinin family, which is a loop structure consisting of seven amino acids at the C-terminus of AMPs [14]. Combined with the predicted results of the secondary structure from the PEP-FOLD3 online software (Fig. 4), it was shown that the secondary structure of GV30 consisted of two parts, including an N-terminal α-helical structure and a C-terminal loop structure (i.e., “Rana box”). Its derivatives, GV23, GV21, GV20, GV12, GV11 and GV8, had a single α-helix structure, and the length of the helix decreased along with the C-terminal truncation. It was worth noticing that, unlike other derivatives, GV18 retained the “Rana box” structure of the parent peptide, and its structure consisted of two parts: a short α-helix at the N-terminus and a loop structure at the C-terminal end.

Fig. 4.

The three-dimensional structures of GV30 and its derivatives were predicted by PEP-FOLD3.

3.3. Screening the antibacterial effect of GV30 and its derivatives

In vitro antibacterial activities of all the synthesised peptides were evaluated by the MIC/MBC determination assay (Table 2). It was clear that the parent peptide, GV30, exhibited a potent antibacterial effect (MIC = 2 μM against S. aureus, MIC = 4 μM against E. coli) for both Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria. As for its derivatives, only three (GV23, GV21, GV20) retained the antibacterial ability. Although GV23 lacked the “Rana box” structure with the number of net charges also reduced, it showed the same antibacterial ability as the parent peptide GV30, which revealed that the “Rana box” did not play an important role in the antibacterial effect of GV30. The derivatives GV21, GV20, GV12 and GV8, which were designed by the prediction of the Expasy PeptideCutter tool, showed different antibacterial activities as continuing to shorten the sequence length and decrease the number of net charges. The antimicrobial effect of GV21 was basically consistent with that of the parent peptide, while that of GV20 was slightly decreased. Further to the above, two N-terminal truncated products, GV18 and GV11, lost their antimicrobial activity. The structure–activity relationship revealed that N-terminal α-helical structure played a vital role in keeping the antibacterial activities against tested microorganisms.

Table 2.

The MIC/MBC (μM) of peptides against selected microorganisms.

| Microorganism | GV30 | GV23 | GV21 | GV20 | GV18 | GV12 | GV11 | GV8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | 2/4 | 2/16 | 2/4 | 4/8 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| E. coli | 4/8 | 4/8 | 4/8 | 8/32 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| MRSA (NCTC 12493) | 2/4 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 8/8 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| K. pneumoniae | 16/64 | 32/64 | 16/16 | 32/64 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| E. faecium | 4/8 | 16/16 | 4/8 | 16/64 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| P. aeruginosa | 16/32 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 32/64 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

Compared to the antibacterial effects of the peptides on the six tested bacteria, it was found that GV30 and its derivatives had a better antibacterial ability on Gram-positive bacteria than against Gram-negative bacteria. Among these, the antibacterial activity against S. aureus and MRSA was the best.

3.4. Antimicrobial activity of GV30 and its derivatives against MRSA

In order to better study the antibacterial effects of GV30 and its derivatives against MRSA, multiple strains of MRSA, MRSA (NCTC 12493), MRSA (BO38 V1S1 A), MRSA (BO42 V2E1 A) and MRSA (ATCC BAA 1707) were selected for antibacterial experiments (Table 3). GV30 showed significant antibacterial activity towards four types of MRSA strains. Among them, the antibacterial ability on MRSA (NCTC 12493) and MRSA (BO38 V1S1 A) was the best (MIC = 2 μM), while the antibacterial ability against MRSA (ATCC BAA 1707) was slightly inferior (MIC = 8 µM). For its derivatives, the antibacterial activity of GV23, without the “Rana box” structure, was the same as the parent peptide on the four tested MRSA strains. Another important aspect in these results is that the antibacterial effect of the truncated GV21 against the clinical strain MRSA (ATCC BAA 1707) was improved (MIC = 4 μM) compared to the GV30 (MIC = 8 µM). In addition, GV20 exhibited a weaker antibacterial activity than the parent peptide, and there was no bactericidal activity observed for the truncated products, GV12, GV8, GV18 and GV11 towards these four MRSA strains. These results indicated that GV21 had a great potential in dealing with clinical MRSA strains.

Table 3.

The MIC/MBC (μM) of peptides against different MRSA strains.

| Microorganism | GV30 | GV23 | GV21 | GV20 | GV12 | GV8 | GV18 | GV11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA (NCTC 12493) | 2/4 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 8/8 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| MRSA(BO38 V1S1 A) | 2/8 | 2/8 | 8/8 | 16/32 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| MRSA(BO42 V2E1 A) | 4/8 | 8/8 | 8/16 | 32/64 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| MRSA(ATCC BAA 1707) | 8/16 | 8/8 | 4/8 | 16/32 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

3.5. Anti-biofilm activities of GV30 and its analogues against S.aureus and MRSA strains

GV30 and its derivatives were assessed for anti-biofilm activity using the crystal violet staining method and showed distinctly inhibitory effects on the biofilms of tested bacteria strains (Table 4). Similar to the antibacterial experiment results, GV30, GV23 and GV21, still retained a strong ability to inhibit biofilm formation. Compared with GV30, the anti-biofilm activities of GV23, which had lost the “Rana box” structure, remained unchanged, while the designed product GV21 had an enhanced anti-biofilm activity against the clinical strain MRSA (ATCC BAA 1707). The effect of GV20 was reduced compared to GV30. At the same time, other modified peptides (GV18, GV8, GV12 and GV11) lost their antibiofilm ability. On the other hand, compared with the ability to inhibit biofilm growth, the MBEC value was significantly higher than the MBIC value. These results revealed that the loop structure, “Rana box”, was not responsible for the anti-biofilm effect of GV30, and the appropriate charge number and peptide length will affect the anti-biofilm activity of the AMPs.

Table 4.

MBIC/MBEC valves (μM) of peptides against tested bacteria.

| Microorganism | GV30 | GV23 | GV21 | GV20 | GV12 | GV8 | GV18 | GV11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus(NCTC 10788) | 2/512 | 2/512 | 2/512 | 8/512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| MRSA (NCTC 12493) | 8/512 | 4/256 | 4/256 | 8/512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| MRSA (BO38 V1S1 A) | 16/256 | 16/256 | 16/512 | 32/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| MRSA (BO42 V2E1 A) | 8/512 | 8/512 | 8/512 | 8/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

| MRSA (ATCC BAA 1707) | 32/>512 | 8/256 | 4/256 | 8/512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 | >512/>512 |

3.6. Activity against persister cells

To explore the effects of GV30 and its derivatives on persister cells, the biofilm was first treated with high concentrations of antibiotics for 24 h to obtain persister cells, and then the ability to inhibit these persister cells at different concentrations of peptides was assessed (Table 5). The results showed that, compared with the anti-biofilm results, GV30 and its derivatives had a more substantial effect on persister cells. Among these, GV21 showed the most significant anti-persister cells effect, and the MBEC value for MRSA (NCTC 12493) and MRSA (BO38 V1S1 A), both reached 64 μM.

Table 5.

The MBEC values (μM) of peptides against persister cells of different MRSA strains.

| Microorganism | GV30 | GV23 | GV21 | GV20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA (NCTC 12493) | 512 | 256 | 64 | >512 |

| MRSA (BO38 V1S1 A) | 128 | 64 | 64 | >512 |

| MRSA (BO42 V2E1 A) | 512 | 256 | 128 | 256 |

| MRSA (ATCC BAA 1707) | >512 | 256 | 256 | 512 |

3.7. MRSA-killing kinetics

In the present investigation, a time-killing assay was studied using MIC and 2*MIC concentrations of each peptide to understand the bactericidal kinetics of GV30 and its derivatives on MRSA (NCTC 12493) (Fig. 5). The results showed that GV23 and GV21 could kill all bacteria within 60 min at their MIC concentrations. GV21 had faster bactericidal kinetics than GV23, while GV30 could not kill all bacteria in three hours. Similarly, at the concentration of 2*MIC, GV23 and GV21 could kill bacteria more rapidly (15 min). Besides, GV20 could kill all bacteria at 90 min. However, GV30 had the slowest bactericidal kinetics, and it killed all bacteria only after 180 min at 2*MIC concentration. The established fact said that the “Rana box” was the reason for the slow antibacterial rate of GV30. Besides, an appropriate number of net charges and peptide length of antimicrobial peptide were crucial to its bactericidal speed.

Fig. 5.

Time-killing curves of GV30 and its derivatives against MRSA at (A) MIC concentration and (B) 2*MIC concentration. The error bars in the graphs around mean data points indicated the standard error of the mean (SEM) for each set of data in the nine replicates from three experiments.

3.8. GV30 and GV21 in the treatment of larvae infected with MRSA

To better compare the antibacterial effect of GV30 and its modified product GV21 on MRSA (NCTC 12493) in vivo, a larvae infected model was used to evaluate the therapeutic effect of these two peptides (Fig. 6). Compared to GV30, GV21 has a better therapeutic effect on larvae that had been infected with MRSA. At the maximum dose of the peptide (25 mg/kg), the five-day survival rate with GV30 could reach 20%, while that of GV21 could reach 40%. At 12.5 mg/kg, both the GV30 treated group and the GV21 treated group died at the 96th hour. Compared with GV30, GV21 worked faster in the first 48 h. At a peptide concentration of 6.25 mg/kg, GV21 had a survival rate of 0% at the 96th h, while larvae treated with GV30, were all dead after 72 h.

Fig. 6.

The mortality of Galleria mellonella larvae infected with MRSA (NCTC 12493) treat by (A) GV30 (25 mg/kg, 12.5 mg/kg, 6.25 mg/kg), (B) GV21 (25 mg/kg, 12.5 mg/kg, 6.25 mg/kg). The infected larvae treated with 50 mg/kg of vancomycin were regarded as the positive control, the infected larvae treated with PBS were regarded as the negative control.

3.9. Kinetic SYTOX green permeability

In order to study the cell membrane permeability of GV30 and its derivatives, a SYTOX green permeability test was conducted (Fig. 7). At a peptide concentration of MIC, these experiments were performed on S.aureus (NCTC 10788) and MRSA (NCTC 12493). The experimental results showed that for S.aureus, all tested peptides finally reached about 100% membrane rupture rate after two hours of incubation; in particular, GV23 and GV21 had the fastest membrane permeability rates and the maximum instantaneous permeability effects. For MRSA, unlike S.aureus, not all peptides had achieved a 100% membrane permeability rate at two hours. Among them, GV23 had the fastest rate of rupture, and GV30 had the slowest.

Fig. 7.

Kinetics of membrane permeabilisation of GV30, GV23, GV21 and GV20 on (A) S.aureus (NCTC 10788) and (B) MRSA (NCTC 12493) at MIC concentration. The percentage of membrane permeabilisation was measured using bacterial cells treated with melittin. The error bars in the graphs around mean data points indicated the standard error of the mean (SEM) for each set of data in the nine replicates from three experiments.

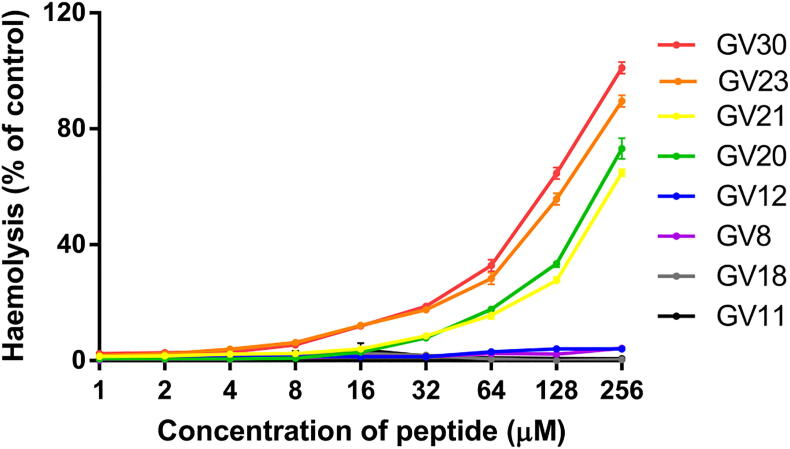

3.10. Haemolytic and cytotoxic activities

The main aim of the present investigation was to obtain a derivative with a potent therapeutic effect through rational modification and get a clear picture of the structure-activity relationship of GV30; thus, it is necessary to study and analyse the toxicity of these designed products. All the synthesised peptides were evaluated for their in vitro haemolysis activity using horse erythrocytes. On the basis of the present investigation, it was clear that, compared with the parent peptide GV30, the haemolysis of its truncated derivatives was reduced (Fig. 8 and Table 6). Among them, the modified products, GV18, GV12, GV11 and GV8, caused a lower level of haemolysis. After truncating the “Rana box” structure, GV23 exhibited decreased lysis of red blood cells while maintaining antibacterial activity. In addition, the haemolysis of GV21 was significantly reduced (HC10 = 45.526 μM) and had only 4.05 % haemolysis at the maximum MIC value.

Fig. 8.

The haemolytic activity of GV30 and derivatives at concentrations of 1 to 256 μM. The percentage was calculated based on the effect induced by a positive control, 1% Triton X-100. Treatment with PBS was used as a negative control. The error bars in the graph around mean data points indicated the standard error of the mean (SEM) in the nine replicates from three individual experiments.

Table 6.

The HC50, HC10 and the haemolysis rate at the MIC valve of GV30 and its derivatives.

| Peptide name | Haemolysis at the maximum MIC (%) | HC10μM) | HC50(μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GV30 | 11.89% | 16.4 | 95.749 |

| GV23 | 17.55% | 16.148 | 115.29 |

| GV21 | 4.05% | 45.526 | 204.519 |

| GV20 | 7.8% | 41.32 | 179.836 |

| GV12 | – | – | – |

| GV8 | – | – | – |

| GV18 | – | – | – |

| GV11 | – | – | – |

“–” represent beyond the statistical scope.

The present study assessed the cytotoxicity of GV30 and its derivatives on HaCaT cells by LDH release assay. The results showed that the maximum LDH release rate by GV21 was observed at the concentration of 100 μM with a release rate of 22.36% compared to the positive control (Fig. 9). At a concentration of 10 µM, only GV30 had cytotoxicity on the HaCaT cell line, and its derivatives did not show a significant effect on this normal cell line. When the peptide concentration was ≤ 1 µM, there was no significant leakage of LDH from the HaCaT cell line after 24 h of incubation with GV30 derivatives. It seems that the removal of the “Rana box” structure was the key factor leading to the decrease of toxicity of GV30 derivatives. On the other hand, GV21 was the truncated product with the lowest toxicity to the HaCaT cell line while maintaining the antibacterial activity.

Fig. 9.

The release of LDH from HaCaT cells. The percentage was calculated based on the effect induced by a positive control, 1% Triton X-100. Treatment with PBS was used as a negative control. The error bars in the graph around mean data points indicated the standard error of the mean (SEM) in the nine replicates from three experiments.

3.11. Antimicrobial activity stability of GV30 and its derivatives in serum and with salt ions

In order to explore the stability of antimicrobial activity of these peptides in various salt solutions and with horse serum, several experiments were performed (results shown in Table 7 and Table 8). The results showed that for the various salts tested, GV30, GV23 and GV21, maintained stable antibacterial effects. However, for GV20, stability was reduced when treated with KCl, CaCl2 or horse serum.

Table 7.

The MIC values (μM) of peptides against S. aureus (NCTC 10788) with different salts and horse serum.

| Peptide name | PBS | NaCl | KCl | NH4Cl | MgCl2 | CaCl2 | ZnCl2 | FeCl3 | Horse serum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GV30 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| GV23 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| GV21 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| GV20 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

Table 8.

The MIC values (μM) of peptides against MRSA (NCTC 12493) with different salts and horse serum.

| Peptide name | PBS | NaCl | KCl | NH4Cl | MgCl2 | CaCl2 | ZnCl2 | FeCl3 | Horse serum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GV30 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| GV23 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| GV21 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| GV20 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 16 |

4. Discussion

As a common nosocomial infectious bacterium, MRSA can cause severe skin infections, necrotising pneumonia, and even more life-threatening diseases [40], [41]. Clinical studies have found that the mortality rate of bacterial infections caused by hospital MRSA is much greater than that of other S.aureus infections [42].

AMPs, in general, are positively charged, short amphiphilic peptides [43]. Their positive charges can facilitate their ready attachment to negatively-charged substances, e.g., phosphatidylglycerol (PG) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), on cell membranes. AMPs can destroy the cell membrane and rapidly kill the cell due to their amphiphilic properties [44]. As a consequence of their good performance in not producing widespread resistance and their significant toxicity towards bacteria, AMPs have become the last tools to treat serious infections, e.g., colistin [45].

In this study, a novel AMP, GV30, from Hylarana guentheri skin secretion, was identified by “shotgun” cloning. According to the UniProt database, the homology comparison between GV30 and other brevinin-2 peptides revealed high levels of identity and thus it was determined that GV30 belonged to the brevinin-2 peptide family. After conducting an antibacterial activity test on GV30, it was found to have a strong broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. The reason may be because the six net positive charges can make this peptide more efficiently bind to the negatively charged substances on the bacterial membrane surfaces, and the concentrated hydrophobic face makes it easier for the peptide to interact with the bilayer to form transmembrane pores [46]. Compared to the six tested bacteria, it was found that GV30 had a more potent antibacterial ability against Gram-positive bacteria compared with Gram-negative bacteria. Among these tested strains, it had the most substantial antibacterial effect against MRSA and had the potential to become a specialised anti-MRSA drug. In the biofilm test, at a low concentration, GV30 could inhibit biofilm formation while the MBEC was much larger than the MBIC, which often necessitated a high concentration of peptides to function. This may be due to the reduced susceptibility of biofilm bacteria leading to the increase of resistance and tolerance to antibiotics [47], [48]. GV30 also showed salt stability and serum stability. It could maintain a good antibacterial effect against MRSA under various physiological salt environments. Moreover, the haemolysis test on GV30 found that at each MIC concentration, it showed a low level of haemolysis to the red blood cells. This is due to the fact that the surface of normal mammalian cells is zwitterionic, making it difficult for the peptide to bind [49]. By analysing the results of haemolysis tests, when the concentration was over 32 μM, the haemolysis had a sharp increase. This can be attributable to the accumulation of peptides bound to the cell membrane gaining threshold, therefore quickly destroying the cell membrane [49]. As for cytotoxicity, it was found that for the HaCaT cell line, GV30 exhibited toxicity at 10 µM. Thus the high cytotoxicity is one of the problems that needs to be solved urgently. The reason may be that the hydrophobicity of the peptide is too high, which leads to high toxicity to normal cells [50].

In order to retain the antibacterial activity of GV30 and reduce its toxicity, a series of modifications to GV30 was made. Firstly, a highly conserved heptapeptide motif in the brevinin family sequence, the “Rana box”, was removed to obtain the first modified peptide GV23. The researchers have different interpretations of the role of the “Rana box” in the sequence of AMPs [51]. Some researchers believe that removing the “Rana box” will only change the structure of the AMP without affecting its antimicrobial effect [52], [53]. In contrast, studies have confirmed that removing the “Rana box” will eliminate the antibacterial effect [14]. Obviously, the role of the “Rana box” is unclear, which is different in different peptides. The results showed that the “Rana box” structure in the GV30 did not seem to impact its antibacterial effect. At the same time, the haemolytic ability and toxicity of the modified product GV23 had been reduced. Surprisingly, compared to GV30, GV23 showed faster antibacterial kinetics both in the time-killing test and the SYTOX green permeability test. A possible explanation is that the N-terminal amidation exposed an N-terminal positive charge and enhanced the structural stability of α-helix [54], [55]. In this step, a safer derivative of GV30 was obtained while retaining antibacterial activity. The results proved that the antibacterial ability of GV30 was not influenced by the “Rana box” structure. Meanwhile, the toxicity and the bacteria-killing kinetics had been changed due to the removal of the “Rana box” structure.

Next, in order to explore the critical antibacterial structure of GV30 and continue to shorten the sequence length, increase stability, and to reduce toxicity, GV23 was further modified to obtain four new derivatives, GV21, GV20, GV12 and GV8. Although AMP drugs have made a considerable progress and an increasing number of AMPs have been discovered or studied, AMPs are still limited to tropical administration or intravenous administration due to the degradation and the difficulty of absorption in the digestive tract [56]. Trypsin, the main protease that works in the small intestine, has always been a key substance that hinders the stability of AMPs in the digestive tract. There are seven trypsin cleavage sites in the sequence of GV30. Thus, the trypsin stability of GV30 and the antibacterial activity and stability of the possible digestion products are necessary to be studied [57]. The performance of these derivatives was different. First of all, the antibacterial effect of GV21 was retained compared with GV30, while the cell cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity were significantly reduced. This result was significant because decreasing cell cytotoxicity and haemolytic activity may help reduce various side effects caused by the excessive haemolytic ability of AMPs, such as haemolytic anaemia [58]. Surprisingly, GV21 showed better antibacterial activity than GV 30 in the in vivo infection model. GV20 was safer than GV30, but its antibacterial activity was reduced, and its sensitivity to salt and serum was improved. GV12 and GV8 completely lost their antibacterial activity, suggesting that their sequences did not contribute to the antibacterial activity of GV30. It may also be due to the lower net charges in GV12 and GV8, which reduces the affinity between peptides and bacteria membrane [59].

The α-helix structure is usually supposed to play an important role in the function of AMPs because such a structure allows the peptides to interact optimally with the amphiphilic structure of the cell membranes [60]. In order to further explore the reason for the disappearance of the antibacterial ability of GV12 and GV8, the sequence of GV12 was removed from the sequence of GV30 and GV23, respectively, consequently generating GV18 and GV11. It was found that these two derivatives did not have biological activity; thus, the sequence of GV12 had been proposed as a supporter for the antibacterial effect of GV30. The possible reason may be that the complete α-helix structure of the N-terminus of GV30 was destroyed, leading to the loss of its antibacterial effect [60], [61].

Subsequently, a preliminary exploration of the possible antibacterial mechanism of GV30 and its derivatives was carried out. It was found that GV30 and derivatives with antibacterial effects could cause membrane destruction in S. aureus and MRSA, thus proving bacteria cell membrane permeabilisation is one of the antibacterial mechanisms of GV30 and its derivatives. Through the SYTOX green permeability test, it was also found that peptides had slightly different killing mechanisms for S. aureus and MRSA. For example, all peptides active against S. aureus finally reached a permeability rate of about 100%. While MRSA was different, compared with GV30, other tested derivatives had a faster membrane permeability rate, consistent with the experimental results obtained in the time-killing assay.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the antibacterial peptide GV30 was successfully identified in the skin secretions of the frog, Hylarana guentheri, and was found to be a brevinin-2 peptide family member with good antibacterial activity, especially for MRSA. By studying the structure–activity relationship of GV30, the N-terminal α-helix structure was found to play a significant role in the antimicrobial activity; in contrast, the C-terminal loop structure did not affect the antimicrobial activity. Besides, removing this loop can reduce toxicity and improve the action speed of GV30. Moreover, it is feasible to use the method of predicting trypsin enzymatic hydrolysis products to modify AMPs. Herein, GV30 was cleaved at trypsin sensitive sites to obtain seven derivatives. This study successfully generated two peptides with higher selectivity. GV23 and GV21 exhibited an improved antibacterial effect against MRSA in vitro and demonstrated a faster bactericidal effect than the parent peptide. GV21, due to its lower toxicity, shorter sequence, faster-killing speed and the same biological activity and stability as the parent peptide, was considered to have the potential to become a new antibacterial drug candidate against MRSA.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yingxue Ma: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Aifang Yao: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Software. Xiaoling Chen: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Lei Wang: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Chengbang Ma: Project administration. Xinping Xi: Project administration. Tianbao Chen: Conceptualization, Supervision. Chris Shaw: Writing – review & editing. Mei Zhou: Conceptualization, Supervision, Resources.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.08.039.

Contributor Information

Xiaoling Chen, Email: x.chen@qub.ac.uk.

Lei Wang, Email: l.wang@qub.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Qin HL, Zhang ZW, Ravindar L, Rakesh KP. Antibacterial activities with the structure-activity relationship of coumarin derivatives. European journal of medicinal chemistry. 2020;207:112832. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ullas BJ, Rakesh KP, Shivakumar J, Gowda DC, Chandrashekara PG. Multi-targeted quinazolinone-Schiff’s bases as potent bio-therapeutics. Results Chem. 2020;2:100067. doi: 10.1016/j.rechem.2020.100067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qin HL, Liu J, Fang WY, Ravindar L, Rakesh KP. Indole-based derivatives as potential antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistance Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Eur J Med Chem. 2020;194:112245. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X, Marichannegowda MH, Rakesh KP, Qin HL. Master mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus: consider its excellent protective mechanisms hindering vaccine development! Microbiol Res. 2018;212-213:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma SK, Verma R, Kumar KSS, Banjare L, Shaik AB. A key review on oxadiazole analogs as potential methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) activity: Structure-activity relationship studies. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;219:113442. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma SK, Verma R, Xue F, Thakur PK, Girish YR. Antibacterial activities of sulfonyl or sulfonamide containing heterocyclic derivatives and its structure-activity relationships (SAR) studies: A critical review. Bioorg Chem. 2020;104400 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Manukumar HM, Rakesh KP, Karthik CS, Nagendra Prasad HS. Role of BP* C@ AgNPs in Bap-dependent multicellular behavior of clinically important methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) biofilm adherence: a key virulence study. Microb Pathog. 2018;123:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manukumar HM, Chandrasekhar B, Rakesh KP, Ananda AP, Nandhini M. Novel TC@ AgNPs mediated biocidal mechanism against biofilm associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Bap-MRSA) 090, cytotoxicity and its molecular docking studies. MedChemComm. 2017;8(12):2181–2194. doi: 10.1039/c7md00486a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma R, Verma SK, Rakesh KP, Girish YR, Ashrafizadeh M. Pyrazole-based analogs as potential antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistance Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and its SAR elucidation. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;113134 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.113134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rakesh KP, Ramesh S, Gowda DC. Effect of low charge and high hydrophobicity on antimicrobial activity of the quinazolinone-peptide conjugates. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2018;44(2):158–164. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(3):238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sierra JM, Fusté E, Rabanal F, Vinuesa T, Viñas M. An overview of antimicrobial peptides and the latest advances in their development. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17(6):663–676. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2017.1315402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson BW, Tang DZ, Mandrell R, Kelly M, Spindel ER. Bombinin-like peptides with antimicrobial activity from skin secretions of the Asian toad, Bombina orientalis. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(34):23103–23111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X, Zhang L, Ma C, Zhang Y, Xi X, et al. (2018) A novel antimicrobial peptide, Ranatuerin-2PLx, showing therapeutic potential in inhibiting proliferation of cancer cells. Bioscience reports 38(6): BSR20180710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Kang SJ, Park SJ, Mishig-Ochir T, Lee BJ. Antimicrobial peptides: therapeutic potentials. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 2014;12(12):1477–1486. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.976613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morikawa N, Hagiwara K, Nakajima T. Brevinin-1 and-2, unique antimicrobial peptides from the skin of the frog, Rana brevipoda porsa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189(1):184–190. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91542-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie H, Zhan Y, Chen X, Zeng Qi, Chen D. Brevinin-2 drug family—new applied peptide candidates against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and their effects on Lys-7 expression of innate immune pathway DAF-2/DAF-16 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Appl Sci. 2018;8(12):2627. doi: 10.3390/app8122627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savelyeva A, Ghavami S, Davoodpour P, Asoodeh A, Łos MJ. An overview of Brevinin superfamily: structure, function and clinical perspectives. Anticancer Genes. 2014:197–212. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4471-6458-6_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conlon JM, Ahmed E, Condamine E. Antimicrobial properties of brevinin-2-related peptide and its analogs: efficacy against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74(5):488–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conlon JM, Sonnevend Á, Patel M, Al-Dhaheri K, Nielsen PF. A family of brevinin-2 peptides with potent activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the skin of the Hokkaido frog, Rana pirica. Regulatory peptides. 2004;118(3):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghavami S, Asoodeh A, Klonisch T, Halayko AJ, Kadkhoda K. Brevinin‐2R1 semi‐selectively kills cancer cells by a distinct mechanism, which involves the lysosomal‐mitochondrial death pathway. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2008;12(3):1005–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassanvand Jamadi R, Khalili S, Mirzapour T, Yaghoubi H, Hashemi ZS. Anticancer activity of brevinin-2R peptide and its Two analogues against myelogenous leukemia cell line as natural treatments: An in vitro study. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2020;26(2):1013–1020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Popovic S, Urbán E, Lukic M, Conlon JM. Peptides with antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities that have therapeutic potential for treatment of acne vulgaris. Peptides. 2012;34(2):275–282. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdel-Wahab YHA, Patterson S, Flatt PR, Conlon JM. Brevinin-2-related peptide and its [D4K] analogue stimulate insulin release in vitro and improve glucose tolerance in mice fed a high fat diet. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42(09):652–656. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckert R. Road to clinical efficacy: challenges and novel strategies for antimicrobial peptide development. Future Microbiol. 2011;6(6):635–651. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reissmann S, Imhof D. Development of conformationally restricted analogues of bradykinin and somatostatin using constrained amino acids and different types of cyclisation. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11(21):2823–2844. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fairlie DP, Leung D, Abbenante G. Protease inhibitors: Current status and future 3 prospects. J Med Chem. 2000;43(3):305–341. doi: 10.1021/jm990412m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue F, Seto CT. Selective Inhibitors of the serine protease plasmin: Probing the s3 and s3 ‘subsites using a combinatorial library. J Med Chem. 2005;48(22):6908–6917. doi: 10.1021/jm050488k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brinckerhoff LH, Kalashnikov VV, Thompson LW, Yamshchikov GV, Pierce RA. Terminal modifications inhibit proteolytic degradation of an immunogenic mart-127–35 peptide: Implications for peptide vaccines. Int J Cancer. 1999;83(3):326–334. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991029)83:3<326::aid-ijc7>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aurelio L, Brownlee RTC, Hughes AB. Synthetic preparation of N-methyl-α-amino acids. Chem Rev. 2004;104(12):5823–5846. doi: 10.1021/cr030024z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen G, Miao Y, Ma C, Zhou M, Shi Z. Brevinin-2GHk from Sylvirana guentheri and the design of truncated analogs exhibiting the enhancement of antimicrobial activity. Antibiotics. 2020;9(2):85. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9020085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derdowska I, Prahl A, Neubert K, Hartrodt B, Kania A, et al. (2001) New analogues of bradykinin containing a conformationally restricted dipeptide fragment in their molecules. J Peptide Res 57(1):11-18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Vajda T, Szabo T. Specificity of trypsin and alpha-chymotrypsin towards neutral substrates. Acta biochimica et biophysica. Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 1976;11(4):287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hedstrom L. Serine protease mechanism and specificity. Chem Rev. 2002;102(12):4501–4524. doi: 10.1021/cr000033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svenson J, Stensen W, Brandsdal BO, Haug BE, Monrad J. Antimicrobial peptides with stability toward tryptic degradation. Biochemistry. 2008;47(12):3777–3788. doi: 10.1021/bi7019904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X, Zhang L, Wu Y, Wang L, Ma C. Evaluation of the bioactivity of a mastoparan peptide from wasp venom and of its analogues designed through targeted engineering. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14(6):599–607. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.23419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casciaro B, Loffredo MR, Cappiello F, Fabiano G, Torrini L. The antimicrobial peptide temporin g: anti-biofilm, anti-persister activities, and potentiator effect of tobramycin efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24):9410. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zai Y, Ying Y, Ye Z, Zhou M, Ma C. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and improved stability of a D-Amino acid enantiomer of DMPC-10A, the designed derivative of dermaseptin truncates. Antibiotics. 2020;9(9):627. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9090627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun C, Li Y, Cao S, Wang H, Jiang C. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of bovine lactoferricin derivatives with symmetrical amino acid sequences. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):2951. doi: 10.3390/ijms19102951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pantosti A, Venditti M. What is MRSA? Eur Respir J. 2009;34(5):1190–1196. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00007709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otto M. MRSA virulence and spread. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14(10):1513–1521. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanberger H, Walther S, Leone M, Barie PS, Rello J. Increased mortality associated with meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection in the Intensive Care Unit: results from the EPIC II study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38(4):331–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lei J, Sun L, Huang S, Zhu C, Li P. The antimicrobial peptides and their potential clinical applications. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(7):3919. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeaman MR, Yount NY. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55(1):27–55. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karaiskos I, Souli M, Galani I, Giamarellou H. Colistin: still a lifesaver for the 21st century? Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13(1):59–71. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2017.1230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jean-François F, Elezgaray J, Berson P, Vacher P, Dufourc EJ. Pore formation induced by an antimicrobial peptide: electrostatic effects. Biophys J. 2008;95(12):5748–5756. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Monroe D. Looking for chinks in the armor of bacterial biofilms. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(11):e307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wille J, Coenye T. Biofilm dispersion: The key to biofilm eradication or opening Pandora’s box? Biofilm. 2020;2:100027. doi: 10.1016/j.bioflm.2020.100027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Papo N, Shai Y. Can we predict biological activity of antimicrobial peptides from their interactions with model phospholipid membranes? Peptides. 2003;24(11):1693–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Attili AF, Angelico M, Cantafora A, Alvaro D, Capocaccia L. Bile acid-induced liver toxicity: relation to the hydrophobic-hydrophilic balance of bile acids. Med Hypotheses. 1986;19(1):57–69. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(86)90137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Won HS, Kang SJ, Lee BJ. Action mechanism and structural requirements of the antimicrobial peptides, gaegurins. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes. 2009;1788(8):1620–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwon MY, Hong SY, Lee KH. Structure-activity analysis of brevinin 1E amide, an antimicrobial peptide from Rana esculenta. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 1998;1387(1–2):239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lederer AL, Maupin DJ, Sena MP, Zhuang Y. The technology acceptance model and the World Wide Web. Decis Support Syst. 2000;29(3):269–282. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shahmiri M, Mechler A. The role of C-terminal amidation in the mechanism of action of the antimicrobial peptide aurein 1.2. The EuroBiotech Journal. 2020;4(1):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mura M, Wang J, Zhou Y, Pinna M, Zvelindovsky AV. The effect of amidation on the behaviour of antimicrobial peptides. Eur Biophys J. 2016;45(3):195–207. doi: 10.1007/s00249-015-1094-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bruno BJ, Miller GD, Lim CS. Basics and recent advances in peptide and protein drug delivery. Therapeutic delivery. 2013;4(11):1443–1467. doi: 10.4155/tde.13.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olsen JV, Ong SE, Mann M. Trypsin cleaves exclusively C-terminal to arginine and lysine residues. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3(6):608–614. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T400003-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeswani G, Alexander A, Saraf S, Saraf S, Qureshi A. Recent approaches for reducing hemolytic activity of chemotherapeutic agents. J Control Release. 2015;211:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cantini F, Luzi C, Bouchemal N, Savarin P, Bozzi A. Effect of positive charges in the structural interaction of crabrolin isoforms with lipopolysaccharide. J Pept Sci. 2020;26(9) doi: 10.1002/psc.v26.910.1002/psc.3271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Powers JPS, Hancock RE. The relationship between peptide structure and antibacterial activity. Peptides. 2003;24(11):1681–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Y, Guarnieri MT, Vasil AI, Vasil ML, Mant CT. Role of peptide hydrophobicity in the mechanism of action of α-helical antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(4):1398–1406. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00925-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.