Abstract

Synthesizing novel photocatalysts that can effectively harvest photon energy over a wide range of the solar spectrum for practical applications is vital. Porphyrin-derived nanostructures with properties similar to those of chlorophyll have emerged as promising candidates to meet this requirement. In this study, tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP) nanofibers were formed on the surface of ZnO nanoparticles using a simple self-assembly approach. The obtained ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composites were characterized via scanning electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction analysis, and ultraviolet–visible absorbance and reflectance measurements. The results demonstrated that the ZnO nanoparticles with an average size of approximately 37 nm were well integrated in the TCPP nanofiber matrix. The resultant composite showed photocatalytic activity of ZnO and TCPP nanofibers concomitantly, with band gap energies of 3.12 and 2.43 eV, respectively. The ZnO/TCPP photocatalyst exhibited remarkable photocatalytic performance for RhB degradation with a removal percentage of 97% after 180 min of irradiation under simulated sunlight because of the synergetic activity of ZnO and TCPP nanofibers. The dominant active species participating in the photocatalytic reaction were •O2– and OH•, resulting in enhanced charge separation by exciton-coupled charge-transfer processes between the hybrid materials.

1. Introduction

Industrial wastewater is a nonbiodegradable, highly toxic, and carcinogenic agent that poses a severe threat to human health and the environment.1−4 Among the industrial wastewater effluents, dye-contaminated wastewater emanating from painting, mining, food, printing, and paper industries is polluting the environment. The dyes widely present in industrial wastewater are azo, phenothiazine, and triphenylmethane derivatives.5 Among these organic dye derivatives, rhodamine B (RhB), that is highly toxic and soluble in aqueous solution and is involved in many industrial processes, is causing severe health and environmental problems even at a low concentration of 1 ppm.6−11 Therefore, the removal of RhB from wastewater is essential to protect human health and the environment. Many approaches such as coagulation, advanced oxidation processes, redox methods, and adsorption have been employed to remove RhB dye from contaminated water.

Advanced oxidation processes such as photocatalysis, wet oxidation, sonolysis, and Fenton reactions have been extensively studied for environmental remediation.12 Among these, photocatalysis is an effective approach because it converts toxic pollutants into their mineral components.13 Compared to conventional methods, photocatalysis has many advantages; it is a renewable method, it has high pollutant-degrading efficiency, it does not cause any secondary pollution, and it is cost-effective and environmentally friendly.14 Materials such as TiO2, ZnO, Cu2O, g-C3N4, spinel ferrites, Ag, and their combinations have been effectively employed as photocatalysts.15 Recently, many organic semiconductors have attracted the attention of scientists for photocatalysis because they can effectively harvest photons with energy in the visible region of the spectrum. Among these, nanostructured porphyrins with a structure similar to that of chlorophyll pigments in plants can be easily fabricated and utilized as photocatalysts to remove contaminants in wastewater.16−22 Supramolecular self-assembly of molecules from the basic building blocks of monomeric porphyrin molecules is a common approach used to synthesize nanostructured porphyrins.23−27 Based on the structure of the porphyrin derivatives, self-assembly of the porphyrin supramolecular can be implemented via reprecipitation and surfactant assistance using ionic solvents.28−30 Many nanostructured porphyrins with controlled morphologies have been reported and utilized as photocatalysts with high photocatalytic performance.30−34 However, to improve the photocatalytic efficiency and stability, the combination of porphyrin nanomaterials with inorganic semiconductors is usually employed.35−37 This combination enables the resultant composite to absorb the photon energy over a wide range of light spectra with enhanced charge separation because of charge transfer between the semiconductor interface.

Zinc oxide (ZnO) with low-cost fabrication, strong oxidizing property, and nontoxicity has been widely used for antifouling, photocatalytic, and antibacterial applications.38 With a band gap energy of approximately 3.37 eV, ZnO can absorb photons with energy in the ultraviolet (UV) region, and it shows outstanding photocatalytic activity. When ZnO is irradiated with UV light, which has a photonic energy higher than the band gap energy, the electrons in the valence band rise up to the conduction band and electron/hole pairs are generated. These electron/hole pairs can migrate to the ZnO surface and participate in the redox reaction to form active hydroxyl radicals and superoxide species for the oxidation processes. However, the electrons and holes can easily combine to release energy in the form of photons, which significantly reduces the photocatalytic activity, consequently hindering their practical application. To improve the charge separation and light harvesting in the visible spectrum, a composite of ZnO with semiconductors and supporting materials is utilized for enhancing the photocatalytic performance.38 Photosensitive molecules such as porphyrins are incorporated on the surface of ZnO to lower the band gap energy to absorb photons with energy in the visible region.36,39 However, the key role of porphyrin derivatives in the reported study is as a dye sensitizer to improve the probability of absorption of photons with energy in the visible region. The photocatalytic behavior of the ZnO/nanostructured porphyrin composites obtained by reprecipitation self-assembly approach has not been reported yet. Herein, the nanostructured porphyrin plays the role of a photocatalyst, active in the visible region.

In this study, a ZnO/porphyrin nanofiber composite was fabricated by a reprecipitation self-assembly technique using ZnO nanoparticles and a monomeric tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP) precursor. The fabricated composite was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and UV–vis absorbance and reflectance (UV–vis) spectroscopy analyses. The ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite was employed as a photocatalyst to degrade RhB in an aqueous solution. The photocatalytic performance of the composite toward RhB dyes was investigated and discussed in addition to the proposed photocatalytic mechanism.

2. Results and Discussion

UV–vis spectroscopy was utilized to study the optical properties of the monomeric TCPP molecules and the prepared ZnO/TCPP nanofibers, and the results are shown in Figure 1. An intense Soret band at a wavelength of approximately 412 nm was observed in the UV–vis spectrum of the TCPP monomer. This Soret absorption peak is attributed to the a1u(π) → e*g(π) transition in the porphyrin core.41 In addition, the UV–vis spectrum of the monomeric TCPP molecule contains four Q bands in the range of 500–700 nm, which result from the a2u(π) → e*g(π) transitions in the porphyrin core.42,43 Interestingly, the Soret absorption band of TCPP appeared at approximately 407 nm in the UV–vis spectrum of ZnO/TCPP and was broadened. This shift of 5 nm in the Soret peak indicates that the monomeric TCPP was successfully self-assembled and followed the J-type aggregation mode to form a well-defined structure on the ZnO surface, as shown in the following section. Further, the four Q bands in the UV–vis spectrum of the TCPP monomer transformed to one strong peak at approximately 580 nm with a shoulder, as observed in the UV–vis spectrum of ZnO/TCPP nanofiber following the self-assembly, indicating the J-type aggregation of the TCPP monomer on the ZnO surface. The peak at 320 nm in the ZnO/TCPP UV–vis spectrum is attributed to the absorption of the ZnO nanoparticles in the composite.44

Figure 1.

UV–vis spectra of TCPP monomer and the ZnO/TCPP nanofiber.

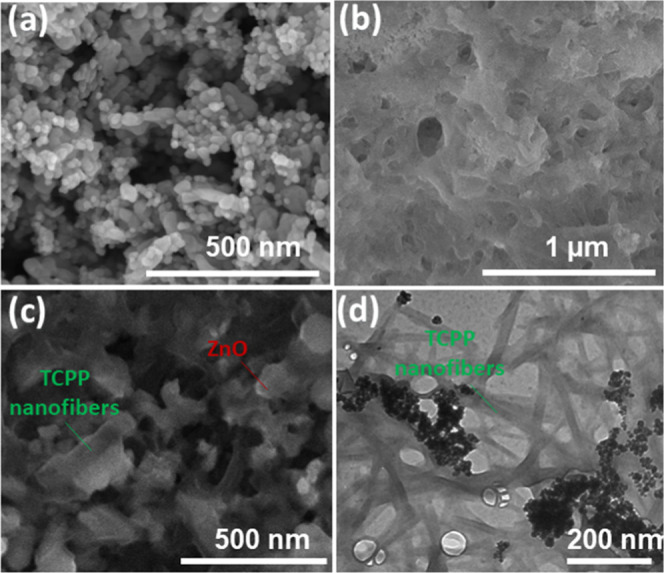

The morphologies of the ZnO nanoparticles, free-standing TCPP nanofibers, and ZnO/TCPP nanofibers were observed using SEM, and the images are shown in Figure 2. ZnO has a regular particle shape with an average diameter of approximately 35 ± 5 nm as observed in Figure 2a. The free-standing assembled TCPP has a one-dimensional structure with a diameter of approximately 40 nm and a length of several micrometers (Figure 2b). When monomeric TCPP nanofibers were assembled on the surface of ZnO, their morphologies were sustained and were well integrated with ZnO nanoparticles in the composite (Figure 2c). The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image (Figure 2d) further confirms the formation of the ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite. The elements distribution in the composite was investigated using energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) mapping as shown in Figure S1. The result shows that the good distribution of the Zn, O, and C elements in the composite demonstrates that TCPP porphyrin is well assembled with ZnO nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

SEM images of (a) ZnO nanoparticles, (b) free-standing assembled TCPP nanofiber, (c) SEM image, and (d) TEM image of ZnO/TCPP fiber composite.

The crystallinity of the materials in the ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composites was investigated using XRD, and the diffraction pattern is presented in Figure 3. The XRD pattern of the composite shows diffraction peaks at 2θ = 32, 35, 36.7, 48, 56.2, 63, 66.7, 67.8, 69, 72.5, and 78.2° corresponding to the (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112), (201), (004), and (202) planes of the ZnO wurtzite (pattern no. 00-036-1451).45,46 Considering the peak positions and widths, the Debye–Scherrer formulation was employed to calculate the average size of the ZnO nanoparticles.47,48 The calculated average size of ZnO nanoparticles was approximately 34 nm, which correlates with the average size observed in the SEM image. In addition, the XRD pattern of the composite contains high-intense diffraction peaks at approximately 33 and 59° (indicated using an asterisk), which are attributed to the TCPP nanofibers, suggesting that the aggregated TCPP is crystalline. These results further substantiate the effective integration of the ZnO nanoparticles in the TCPP nanofiber matrix. The crystallinity and the size of the ZnO/TCPP nanofibers composite were not altered following the integration.

Figure 3.

XRD pattern of ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composites.

To evaluate the photocatalytic activity of the materials, the band gap energy was determined. Figure 4 shows the Tauc plot of the ZnO, TCPP nanofibers, and ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite. The relation between the absorption coefficient and the band gap energy of the materials is given in eq 1,

| 1 |

where α is the absorption coefficient, A is the absorption intensity, h is Planck’s constant with a value of 6.626 × 10–34 J s, Eg is the band gap energy, and υ is the velocity of light (3 × 108 ms–1).

Figure 4.

Tauc plot of ZnO, TCPP nanofibers, and ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite.

The band gap energies of ZnO and free-standing TCPP nanofibers were determined to be 3.21 and 2.6 eV, respectively, using the Tauc plot method. Notably, the Tauc plot of the ZnO/TCPP composite exhibits band gap energies of 3.12 and 2.43 eV, indicating that the prepared hybrid materials demonstrate the photocatalytic effect of ZnO and TCPP nanofiber semiconductors simultaneously, over a wide range of energy in the visible light region. Further, these band gap energies are lower than those of ZnO and free-standing TCPP, establishing the successful incorporation of ZnO and TCPP nanofibers.

Based on the determined band gap energies of the ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite, photocatalytic experiments were performed for RhB removal under simulated sunlight irradiation. Figure 5 shows the effect of varied amounts of ZnO on the photocatalytic performance of ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite for RhB degradation after 180 min of light irradiation. The ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite exhibits higher photocatalytic performance than the TCPP nanofibers and ZnO nanoparticles. In free-standing TCPP nanofibers, approximately 61% of RhB was removed after 180 min of irradiation. The photocatalytic performance of TCPP increased significantly upon the incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles. The RhB removal percentage reached a maximum value of approximately 97% when the TCPP/ZnO weight ratio was 1:5. The increase in the ZnO proportion resulted in a decrease in the RhB removal percentage. Therefore, the TCPP/ZnO composite with a weight ratio of 1:5 was selected as the optimal ZnO/TCPP composite for further evaluation of the photocatalytic activity.

Figure 5.

Effect of varied amounts of ZnO on the photocatalytic efficiency of ZnO/TCPP composite for the RhB degradation under simulated sunlight irradiation.

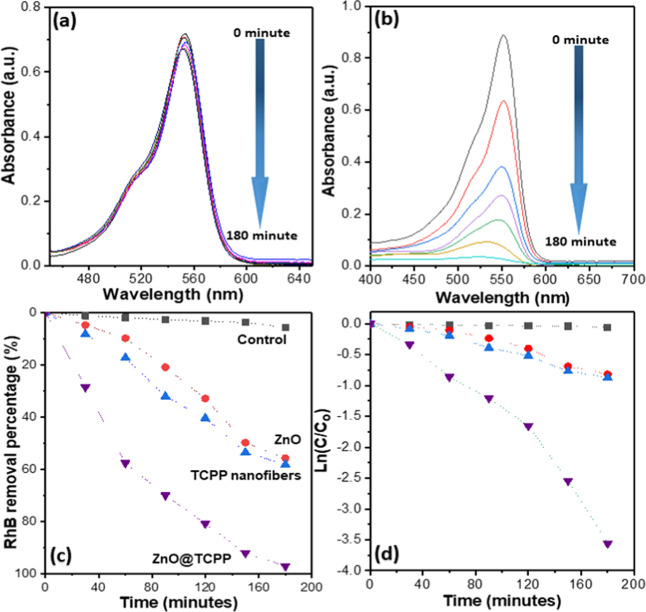

ZnO nanoparticles have been considered effective photocatalysts for the degradation of organic compounds in the UV region.49,50 To enhance the photocatalytic performance, ZnO was additionally incorporated with monomeric porphyrin molecules, which is a photosensitizer; these molecules can effectively harvest photons with energy over a wider range of light region.39 Recently, well-defined porphyrin nanostructures were fabricated via self-assembly with structural and photocatalytic properties similar to those of chlorophyll for photocatalysis applications.30,34,36,41 The band gap energies exhibited by the ZnO/TCPP composite indicate that it can harvest photons with energy in UV and visible regions. In this study, the photocatalytic activities of the ZnO nanoparticles, TCPP nanofibers, and ZnO/TCPP composite were investigated for RhB removal under simulated sunlight irradiation. Figure 6a,b shows the UV–vis spectra of RhB degradation with and without using the ZnO/TCPP photocatalyst, respectively. The RhB concentration decreased significantly when the ZnO/TCPP composite was used as a photocatalyst, which suggests that ZnO/TCPP demonstrates remarkable photocatalytic activity. A significant amount of RhB dye was degraded after 180 min of the experiment (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Effect of treatment time on the RhB removal performances with (a) no photocatalyst and (b) ZnO/TCPP photocatalyst. (c) Removal percentage of RhB and (d) kinetic simulation curve for RhB degradation using various photocatalytic materials.

The RhB removal percentages were calculated by observing the peak intensities at 553 nm, which changed following the photocatalytic reaction. Figure 6 shows the photocatalytic performances of the control, ZnO nanoparticles, free-standing TCPP nanofibers, and ZnO/TCPP composite. The degradation of RhB under simulated sunlight irradiation without a catalyst was not observed in this study, corroborating the published studies; this is illustrated in Figure 6c, which indicates an RhB removal of less than 10% after 180 min of irradiation of the controlled experiment. When ZnO nanoparticles were employed as a photocatalyst, approximately 59% of RhB was removed after 180 min of irradiation. The RhB removal percentage was approximately 60% for the free-standing porphyrin nanofiber photocatalyst. Notably, the incorporation of ZnO and TCPP nanofibers exhibited remarkably enhanced photocatalytic performance toward RhB, with approximately 100% of RhB removed after 180 min of reaction time. The ln (Ct/C0) vs time plot, where Ct is the absorbance intensity of RhB at time t and C0 is the initial absorbance before light irradiation, was graphed to investigate the RhB degradation kinetics of the photocatalytic process (Figure 6d). The calculated degradation rate constants of the ZnO nanoparticles, free-standing TCPP nanofibers, and ZnO/TCPP composite were 4.1 × 10–3, 4.2 × 10–3, and 2 × 10–2 min–1, respectively. These results indicate that the photocatalytic activity of the ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite was 5 times higher than that of ZnO nanoparticles and free-standing porphyrin nanofibers. This may be attributed to the improved light harvesting in the entire visible light region and improved electrons/hole separation of the composite. In addition, the RhB-degrading rate constants of the ZnO/TCPP composite are higher than those of porphyrin-aggregate-based photocatalysts reported in the literature.51,52

The photodegradation efficiency of the ZnO/TCPP nanocomposite was compared with that of reported ZnO-based photocatalysts for RhB, and the values are listed in Table 1. The new ZnO-based materials synthesized in this study exhibit remarkable photocatalytic activity with a relatively low dosage of photocatalysts in comparison to the composites in published studies, with similar photocatalytic experimental conditions.

Table 1. Comparison of the Photodegradation Efficiency of RhB by ZnO/TCPP Nanocomposite and That of Composites in Published Studies with Similar Photocatalytic Experimental Conditions.

| ZnO-based nanocomposites | light source/pollutant | experimental conditions | photodegradation efficiency (%) | refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi2O3/ZnO | 300 W Xe lamp | dosage = 1 g/L [RhB] = 4.8 mg | 85 | (37) |

| rhodamine B | irradiation time = 180 min | |||

| CdS/ZnO | 300 W Xe lamp | dosage = 0.5 g/L | 100 | (53) |

| rhodamine B | [RhB] = 24 mg/L | |||

| irradiation time = 180 min | ||||

| CuO/ZnO | 300 W Xe lamp | dosage = 0.3 g/L | 100 | (54) |

| rhodamine B | [RhB] = 24 mg/L | |||

| irradiation time = 120 min | ||||

| CeO2/ZnO | 8 W UV light | dosage = 0.5 g/L | 98 | (55) |

| rhodamine B | [RhB] = 24 mg/L | |||

| irradiation time = 180 min | ||||

| SiO2/ZnO | UV light | dosage = N/A | 93 | (56) |

| rhodamine B | [RhB] = 4.8 mg/L | |||

| irradiation time = 100 min | ||||

| Sr-ZnO | 1000 W Xe lamp | dosage = 1 g/L | 92 | (57) |

| rhodamine B | [RhB] = 10 mg/L | |||

| irradiation time = 180 min | ||||

| porphyrin-sensitized ZnO | 1000 W halogen–tungsten lamp | dosage = 2 g/L | degradation rate constant = 5.03 × 10–2 min–1 | (58) |

| rhodamine B | [RhB] = 1 × 10–5 mol/L | |||

| irradiation time = 60 min | ||||

| porphyrin@porphyrin nanofibers | 300 W Xe lamp | dosage = 0.04 g/L | 100 | this study |

| rhodamine B | [RhB] = 5 mg/L | |||

| irradiation time = 180 min |

To confirm the mineralization of small aromatic compounds derived from the photodegradation of RhB by the ZnO/TCPP photocatalyst, the total organic carbon analysis is shown in Figure S2. The total amount of carbon decreases with an increase in photocatalytic time, which may be due to the mineralization of small aromatic compounds to form CO2 and H2O as final products of the photocatalytic process.14

Recyclability is an important factor in evaluating the practical applicability of the photocatalysts. In this study, the recyclability of the ZnO/TCPP photocatalyst was investigated. The catalyst was collected by centrifugation after each photocatalytic cycle, subsequently rinsed, and dried prior to performing the next cycle; in each cycle, the catalyst was irradiated for 180 min. Figure 7 shows the recyclability of the ZnO/TCPP composite photocatalyst for the removal of RhB under simulated sunlight irradiation. The photocatalytic activity of the photocatalyst decreased after each cycle. After five cycles of photocatalysis, the RhB removal percentage was 70% in comparison to 97% in the first cycle. The decrease in the photocatalytic activity after five cycles was 27%; therefore, the ZnO/TCPP composite could be considered as a suitable photocatalyst for dye removal in practical applications.

Figure 7.

Recyclability of the ZnO/TCPP composite photocatalyst for RhB photodegradation.

ZnO nanoparticles show strong photocatalytic activity in the UV region, which can harvest the photon energy to generate OH• and •O2– active species to decompose organic dyes.59,60 The J-type assembly formed by strong π–π interactions of the conjugated organic dyes can act as an organic semiconductor, which can absorb the photon energy to excite electrons from the valence band to the conduction band to generate electron/hole pairs for the photocatalytic reactions.28,61,62 Further, the incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles and TCPP nanofibers can induce exciton-coupled charge-transfer processes between the hybrid materials, which reduces the probability of the combination of the excited electrons and holes, and as a result, more electrons and holes participate in the photocatalytic reaction. The ZnO/TCPP photocatalyst has band gap energies of 3.12 (ZnO) and 2.43 eV (TCPP nanofibers), enabling the catalyst to harvest the photon energy in the entire light region. In addition, the results indicate that light irradiation did not degrade RhB dye in the absence of a catalyst. Based on the aforementioned discussion and well-reviewed literature, the photocatalytic mechanism of the ZnO/TCPP catalyst for the photodegradation of RhB is proposed, as illustrated in Figure 8. When the hybrid material is irradiated with simulated sunlight, the electrons in the photocatalyst absorb the photons with energy in the UV and visible regions and jump from the valence band to the conduction band, thereby leaving holes in the valence band.41 This generates electron/hole pairs in the photocatalyst, which tend to move between the ZnO/TCPP interface. The generated electrons move from the conduction band of the TCPP nanofibers to that of the ZnO; however, the holes tend to move in the opposite pathway, they move from the valence band of ZnO to that of TCPP; as a result, the charge separation of electrons and holes is significantly improved. The generated electrons in the hybrid materials reduce O2 in the photocatalytic media to •O2– active species. The hole participates in the oxidation of OH– to form OH• radicals. The •O2– and OH• active species migrate to the RhB surface and oxidize them, resulting in degraded products of CO2 and H2O.

Figure 8.

Proposed photocatalytic mechanism of the ZnO/TCPP photocatalyst for the RhB degradation.

3. Conclusions

In summary, a ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite was successfully fabricated via simple self-assembly of monomeric TCPP porphyrin molecules on the surface of ZnO nanoparticles. The prepared ZnO/TCPP composite showed a well-defined TCPP fiber structure with a diameter of approximately 40 nm and length of several micrometers integrated into the ZnO nanoparticles with an average size of 37 nm. The ZnO/TCPP composite has band gap energies of 3.12 and 2.43 eV, suggesting that it can be utilized as an effective photocatalyst in the entire light region. The ZnO/TCPP photocatalyst exhibited excellent photocatalytic performance for RhB degradation with a photocatalytic rate constant of 2 × 10–2 min–1, which is more effective than the photocatalytic performance of ZnO nanoparticles and free-standing TCPP nanofibers. The incorporation of porphyrin aggregates and ZnO nanoparticles enables the photocatalyst to harvest photons having energy over the entire light region; in addition, it significantly increases the charge separation, consequently enhancing the photocatalytic performance. Further, the photocatalyst exhibits relative stability after each cycle of recyclability, suggesting that it is a suitable and promising application for treating dye-contaminated wastewater.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

Tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP) monomer was purchased from the Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Company. Ammonia solution, Zn(CH3COO)2.2H2O (99%), hexamethylene tetramine (C6H12N4, 99%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 99%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99%), ethanol (99%), and NaClO (99%) were purchased from Xilong Chemicals (China). Double-distilled water was used throughout the experiment.

4.2. Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles

The synthesis procedure of ZnO nanoparticles was adopted from a previous study.40 Herein, 2.19 g of zinc acetate (0.012 mol) and 0.7 g of hexamethylene tetramine (0.005 mol) were dissolved in 100 mL of double-distilled water using a magnetic stirrer. The pH of the stirred solution was adjusted to 8 using an ammonia solution. The resultant solution was poured into an autoclave and subjected to a hydrothermal process for 24 h at a temperature of 150 °C. The precipitates were collected by vacuum filtering, then rinsed thoroughly with water, and dried overnight in an air oven. The ZnO nanoparticles were obtained by calcinating the dried powder at 400 °C for 3 h in a N2 atmosphere.

4.3. Preparation of ZnO/TCPP Nanofiber Composite

The ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite was fabricated using reprecipitation self-assembly (acid–base neutralization) approach.37 The porphyrin solution was obtained by dissolving 8 mg of TCPP precursor in 2 mL of 0.2 M NaOH. Various amounts of ZnO nanoparticles with the TCPP/ZnO ratios in the range of 1:1–1:25 were added to the TCPP solution. The mixed solution was sonicated using a bath sonicator for 20 min to obtain homogeneous ZnO/TCPP mixtures. Then, 0.1 M HCl was added dropwise with continuous stirring to the sonicated solution to obtain a solution with pH 6–7. The precipitates were collected by centrifugation, subsequently washed with distilled water, and then completely dried. For comparison, free-standing TCPP nanofibers were prepared following the same procedure without adding the ZnO nanoparticles.

4.4. Characterization Techniques

An X’Pert PRO PANalytical instrument (Malvern Panalytical Co., the Netherlands) with a Cu Kα radiation source of 0.15405 nm was employed to investigate the structure and crystallinity of the composites. The morphologies of the ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composites were obtained using SEM (Hitachi S-4600, Japan). The optical properties of the composite were studied using UV–vis spectroscopy (Shanghai Yoke Instrument Co., Ltd., China). In addition, the photocatalytic activity of the ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite for the degradation of RhB dye was investigated using a UV–vis spectrophotometer.

4.5. Photocatalytic Experiments

The photocatalytic activity of the ZnO/TCPP nanofiber composite was studied for RhB photodegradation in water. Initially, 10 mL of RhB (5 ppm) was taken in a 20 mL vial; ZnO/TCPP powder (0.4 mg) was added to the solution, and it was sonicated for 30 min. The mixture was placed in the dark for 6 h to attain adsorption/desorption equilibrium prior to performing the photocatalytic experiment. Then, the mixture was mildly shaken and introduced into the photocatalytic chamber with a simulated sunlight source from a 350 W Xenon lamp with effective air cooling (China, 350 W). After a certain duration, the mixture was removed and UV–vis spectroscopy measurement was performed. The change in the RhB concentration was recorded and determined from the absorption spectra at a wavelength of 553 nm. Then, photocatalytic activities of ZnO and free-standing TCPP were investigated following the same procedure without a catalyst for the control experiment. All experiments were performed for three trials, and the average values with derivation of photocatalytic efficiencies were obtained.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Vietnam Maritime University under grant number DT2021.05.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c02808.

EDX mapping for the elements distribution in the ZnO/porphyrin nanofiber composite and total organic carbon during the photocatalytic process of the Rhodamine B by ZnO/porphyrin photocatalyst (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Robinson T.; McMullan G.; Marchant R.; Nigam P. Remediation of dyes in textile effluent: a critical review on current treatment technologies with a proposed alternative. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 77, 247–255. 10.1016/S0960-8524(00)00080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Shao Z.; Chen C.; Wang X. Hierarchical GOs/Fe 3 O 4/PANI magnetic composites as adsorbent for ionic dye pollution treatment. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 38192–38198. 10.1039/C4RA05800C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval A.; Hernández-Ventura C.; Klimova T. E. Titanate nanotubes for removal of methylene blue dye by combined adsorption and photocatalysis. Fuel 2017, 198, 22–30. 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. S.; Kumar V.; Malyan S. K.; Sharma J.; Mathimani T.; Maskarenj M. S.; Ghosh P. C.; Pugazhendhi A. Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) for bioelectrochemical treatment of different wastewater streams. Fuel 2019, 254, 115526 10.1016/j.fuel.2019.05.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor J.; Sharma M.. Impact of Textile Dyes on Human Health and Environment. In Impact of Textile Dyes on Public Health and the Environment; IGI Global, 2020; pp 162–169. [Google Scholar]

- Nestmann E. R.; Douglas G. R.; Matula T. I.; Grant C. E.; Kowbel D. J. Mutagenic activity of rhodamine dyes and their impurities as detected by mutation induction in Salmonella and DNA damage in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cancer Res. 1979, 39, 4412–4417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadirvelu K.; Karthika C.; Vennilamani N.; Pattabhi S. Activated carbon from industrial solid waste as an adsorbent for the removal of Rhodamine-B from aqueous solution: Kinetic and equilibrium studies. Chemosphere 2005, 60, 1009–1017. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inbaraj B. S.; Chien J.; Ho G.; Yang J.; Chen B. Equilibrium and kinetic studies on sorption of basic dyes by a natural biopolymer poly (γ-glutamic acid). Biochem. Eng. J. 2006, 31, 204–215. 10.1016/j.bej.2006.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salleh M. A. M.; Mahmoud D. K.; Karim W. A. W. A.; Idris A. Cationic and anionic dye adsorption by agricultural solid wastes: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2011, 280, 1–13. 10.1016/j.desal.2011.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merouani S.; Hamdaoui O.; Saoudi F.; Chiha M.; Pétrier C. Influence of bicarbonate and carbonate ions on sonochemical degradation of Rhodamine B in aqueous phase. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 175, 593–599. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa Hosseini Asl S.; Ghadi A.; Sharifzadeh Baei M.; Javadian H.; Maghsudi M.; Kazemian H. Porous catalysts fabricated from coal fly ash as cost-effective alternatives for industrial applications: A review. Fuel 2018, 217, 320–342. 10.1016/j.fuel.2017.12.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miklos D. B.; Remy C.; Jekel M.; Linden K. G.; Drewes J. E.; Hübner U. Evaluation of advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment–A critical review. Water Res. 2018, 139, 118–131. 10.1016/j.watres.2018.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan A.; Kumar P. S.; Vo D.-V. N.; Yaashikaa P. R.; Karishma S.; Jeevanantham S.; Gayathri B.; Bharathi V. D. Photocatalysis for removal of environmental pollutants and fuel production: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 19, 441–463. 10.1007/s10311-020-01077-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tran C.; La D. D.; Nguyen T. P.; Ninh H. D.; Vu T. H. T.; Nadda A. K.; Nguyen X. C.; Nguyen D. D.; Ngo H. H. New TiO2-doped Cu–Mg spinel-ferrite-based photocatalyst for degrading highly toxic rhodamine B dye in wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 126636 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Anusuyadevi P. R.; Aymonier C.; Luque R.; Marre S. Nanostructured materials for photocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3868–3902. 10.1039/C9CS00102F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara K.; Hill J. P.; Ariga K. Thin-Film-Based Nanoarchitectures for Soft Matter: Controlled Assemblies into Two-Dimensional Worlds. Small 2011, 7, 1288–1308. 10.1002/smll.201002350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würthner F.; Kaiser T. E.; Saha-Möller C. R. J-Aggregates: From Serendipitous Discovery to Supramolecular Engineering of Functional Dye Materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3376–3410. 10.1002/anie.201002307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Chen P.; Dong H.; Zhen Y.; Liu M.; Hu W. Porphyrin Supramolecular 1D Structures via Surfactant-Assisted Self-Assembly. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 5379–5387. 10.1002/adma.201501273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drain C. M.; Varotto A.; Radivojevic I. Self-organized porphyrinic materials. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 1630–1658. 10.1021/cr8002483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elemans J. A.; van Hameren R.; Nolte R. J.; Rowan A. E. Molecular Materials by Self-Assembly of Porphyrins, Phthalocyanines, and Perylenes. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 1251–1266. 10.1002/adma.200502498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeben F. J.; Jonkheijm P.; Meijer E.; Schenning A. P. About supramolecular assemblies of π-conjugated systems. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1491–1546. 10.1021/cr030070z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.; Kim K.-D.; Lee Y.-K. Conversion of V-porphyrin in asphaltenes into V2S3 as an active catalyst for slurry phase hydrocracking of vacuum residue. Fuel 2020, 263, 116620 10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du C.; Falini G.; Fermani S.; Abbott C.; Moradian-Oldak J. Supramolecular assembly of amelogenin nanospheres into birefringent microribbons. Science 2005, 307, 1450–1454. 10.1126/science.1105675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Lim J.-H.; Chung S.-W.; Mirkin C. A. Self-assembly of mesoscopic metal-polymer amphiphiles. Science 2004, 303, 348–351. 10.1126/science.1093276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winfree E.; Liu F.; Wenzler L. A.; Seeman N. C. Design and self-assembly of two-dimensional DNA crystals. Nature 1998, 394, 539–544. 10.1038/28998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun M.; Han W.; Li B.; Xin X.; Lin Z. An Unconventional Route to Hierarchically Ordered Block Copolymers on a Gradient Patterned Surface through Controlled Evaporative Self-Assembly. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1122–1127. 10.1002/anie.201208421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray P. C. Size and shape dependent second order nonlinear optical properties of nanomaterials and their application in biological and chemical sensing. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 5332–5365. 10.1021/cr900335q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La D.; Hangarge R.; V Bhosale S.; Ninh H.; Jones L.; Bhosale S. Arginine-mediated self-assembly of porphyrin on graphene: a photocatalyst for degradation of dyes. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 643. 10.3390/app7060643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La D. D.; Bhosale S. V.; Jones L. A.; Bhosale S. V. Arginine-induced porphyrin-based self-assembled nanostructures for photocatalytic applications under simulated sunlight irradiation. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 151–154. 10.1039/C6PP00335D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Ho K. J.; Medforth C. J.; Shelnutt J. A. Porphyrin nanofiber bundles from phase-transfer ionic self-assembly and their photocatalytic self-metallization. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 2557–2560. 10.1002/adma.200600539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kharazi P.; Rahimi R.; Rabbani M. Study on porphyrin/ZnFe2O4@ polythiophene nanocomposite as a novel adsorbent and visible light driven photocatalyst for the removal of methylene blue and methyl orange. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 103, 133–141. 10.1016/j.materresbull.2018.03.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K.; Xing R.; Chen C.; Shen G.; Yan L.; Zou Q.; Ma G.; Möhwald H.; Yan X. Peptide-Induced Hierarchical Long-Range Order and Photocatalytic Activity of Porphyrin Assemblies. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 500–505. 10.1002/anie.201409149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N.; Wang L.; Wang H.; Cao R.; Wang J.; Bai F.; Fan H. Self-assembled one-dimensional porphyrin nanostructures with enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 560–566. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aljabri M. D.; La D. D.; Jadhav R. W.; Jones L. A.; Nguyen D. D.; Chang S. W.; Dai Tran L.; Bhosale S. V. Supramolecular nanomaterials with photocatalytic activity obtained via self-assembly of a fluorinated porphyrin derivative. Fuel 2019, 254, 115639 10.1016/j.fuel.2019.115639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La D. D.; Bhosale S. V.; Jones L. A.; Revaprasadu N.; Bhosale S. V. Fabrication of a Graphene@ TiO2@ Porphyrin hybrid material and its photocatalytic properties under simulated sunlight irradiation. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 3329–3333. 10.1002/slct.201700473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La D. D.; Rananaware A.; Thi H. P. N.; Jones L.; Bhosale S. V. Fabrication of a TiO2@ porphyrin nanofiber hybrid material: a highly efficient photocatalyst under simulated sunlight irradiation. Adv. Nat. Sci.: Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 015009 10.1088/2043-6254/aa597e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La D. D.; Nguyen T. A.; Nguyen X. S.; Truong T. N.; Ninh H. D.; Vo H. T.; Bhosale S. V.; Chang S. W.; Rene E. R.; Nguyen T. H.; et al. Self-assembly of porphyrin on the surface of a novel composite high performance photocatalyst for the degradation of organic dye from water: Characterization and performance evaluation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106034 10.1016/j.jece.2021.106034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adnan M. A. M.; Julkapli N. M.; Abd Hamid S. B. Review on ZnO hybrid photocatalyst: impact on photocatalytic activities of water pollutant degradation. Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 36, 77–104. 10.1515/revic-2015-0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W.-j.; Li J.; Mele G.; Zhang Z.-q.; Zhang F.-x. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B by surface modification of ZnO with copper (II) porphyrin under both UV–vis and visible light irradiation. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2013, 366, 84–91. 10.1016/j.molcata.2012.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La D. D.; Nguyen-Tri P.; Le K. H.; Nguyen P. T.; Nguyen M. D.-B.; Vo A. T.; Nguyen M. T.; Chang S. W.; Tran L. D.; Chung W. J. Effects of antibacterial ZnO nanoparticles on the performance of a chitosan/gum arabic edible coating for post-harvest banana preservation. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 151, 106057 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2020.106057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- La D. D.; Tran C. V.; Hoang N. T.; Ngoc M. D. D.; Nguyen T. P.; Vo H. T.; Ho P. H.; Nguyen T. A.; Bhosale S. V.; Nguyen X. C.; et al. Efficient photocatalysis of organic dyes under simulated sunlight irradiation by a novel magnetic CuFe2O4@ porphyrin nanofiber hybrid material fabricated via self-assembly. Fuel 2020, 281, 118655 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; Meng D.; Jiang S.; Wu G.; Yan S.; Geng J.; Huang Y. Multiple-bilayered RGO–porphyrin films: from preparation to application in photoelectrochemical cells. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 18879–18886. 10.1039/c2jm33900e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Zhang C.; Zhang X.; Ou X.; Zhang X. One-step growth of organic single-crystal p–n nano-heterojunctions with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 9200–9202. 10.1039/c3cc45169k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.-K.; Wang Y.-Y.; Zhu L.; Wu J.-Y. Green synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using carboxylic curdlan and their interaction with bovine serum albumin. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 77752–77759. 10.1039/C6RA15395J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zak A. K.; Razali R.; Abd Majid W. H.; Darroudi M. Synthesis and characterization of a narrow size distribution of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 1399. 10.2147/IJN.S19693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad W.; Ullah N.; Haroon M.; Abbasi B. H. Optical, morphological and biological analysis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) using Papaver somniferum L. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 29541–29548. 10.1039/C9RA04424H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La D.-D.; Kim C. K.; Jun T. S.; Jung Y.; Seong G. H.; Choo J.; Kim Y. S. Pt nanoparticle-supported multiwall carbon nanotube electrodes for amperometric hydrogen detection. Sens. Actuators, B 2011, 155, 191–198. 10.1016/j.snb.2010.11.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; Pan Q.; Tian Z.; et al. Grain size control and gas sensing properties of ZnO gas sensor. Sens. Actuators, B 2000, 66, 277–279. 10.1016/S0925-4005(00)00381-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ong C. B.; Ng L. Y.; Mohammad A. W. A review of ZnO nanoparticles as solar photocatalysts: synthesis, mechanisms and applications. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 536–551. 10.1016/j.rser.2017.08.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. M.; Lai C. W.; Ngai K. S.; Juan J. C. Recent developments of zinc oxide based photocatalyst in water treatment technology: a review. Water Res. 2016, 88, 428–448. 10.1016/j.watres.2015.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer R.; Jambeck J. R.; Law K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782 10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La D. D.; Hangarge R. V.; V Bhosale S.; Ninh H. D.; Jones L. A.; Bhosale S. V. Arginine-mediated self-assembly of porphyrin on graphene: a photocatalyst for degradation of dyes. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 643. 10.3390/app7060643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y.; Meng M.; Yu Y.; Wang X.; Ding T. Photoluminescence and photocatalysis of the flower-like nano-ZnO photocatalysts prepared by a facile hydrothermal method with or without ultrasonic assistance. Appl. Catal., B 2011, 105, 335–345. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.04.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Xie W.; Hu X.; Shen G.; Zhou X.; Xiang Y.; Zhao X.; Fang P. Comparison of dye photodegradation and its coupling with light-to-electricity conversion over TiO2 and ZnO. Langmuir 2010, 26, 591–597. 10.1021/la902117c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.; Chen R.; Zhang X.; Shu S.; Xiong J.; Zheng Y.; Dong W. Electrospinning of CeO2–ZnO composite nanofibers and their photocatalytic property. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 1327–1330. 10.1016/j.matlet.2011.01.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai J.; Tao X.; Pu Y.; Zeng X.-F.; Chen J.-F. Core/shell structured ZnO/SiO2 nanoparticles: preparation, characterization and photocatalytic property. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 257, 393–397. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.06.091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Huang J.-F.; Cao L.-Y.; Jia-Yin L.; OuYang H.-B.; Yao C.-Y. Microwave hydrothermal synthesis of Sr2+ doped ZnO crystallites with enhanced photocatalytic properties. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 2647–2653. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.10.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Cheng Y.; Kang S.; Mu J. Preparation and enhanced visible light-driven catalytic activity of ZnO microrods sensitized by porphyrin heteroaggregate. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 6705–6709. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.04.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rokesh K.; Mohan S. C.; Karuppuchamy S.; Jothivenkatachalam K. Photo-assisted advanced oxidation processes for Rhodamine B degradation using ZnO–Ag nanocomposite materials. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 3610–3620. 10.1016/j.jece.2017.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uma R.; Ravichandran K.; Sriram S.; Sakthivel B. Cost-effective fabrication of ZnO/g-C3N4 composite thin films for enhanced photocatalytic activity against three different dyes (MB, MG and RhB). Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017, 201, 147–155. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kano H.; Kobayashi T. Time-resolved fluorescence and absorption spectroscopies of porphyrin J-aggregates. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 116, 184–195. 10.1063/1.1421073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows P. J.; Dujardin E.; Hall S. R.; Mann S. Template-directed synthesis of silica-coated J-aggregate nanotapes. Chem. Commun. 2005, 3688–3690. 10.1039/b502436f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.