Abstract

Background

Community health worker (CHW) motivation is an important factor related to health service quality and CHW program sustainability in low- and middle-income countries. Financial and non-financial motivators may influence CHW behavior through two dimensions of motivation: desire to perform and effort expended. The aim of this study was to explore how the removal of performance-based financial incentives impacted CHW motivation after formal funding ceased for Alive and Thrive (A&T), an infant and young child feeding (IYCF) program in Bangladesh.

Methods

This qualitative study included seven focus groups (n = 43 respondents) with paid supervisors of volunteer CHWs tasked with delivering interpersonal IYCF counseling services. Data were transcribed, translated into English, and then analyzed using both a priori themes and a grounded theory approach.

Results

Results suggest the removal of financial incentives was perceived to have negatively impacted CHWs’ desire to perform in three primary ways: 1) a decreased desire to work without financial compensation, 2) changes in pre- and post-intervention motivation, and 3) household income challenges due to dependence on incentives. Removal of financial incentives was perceived to have negatively impacted CHWs’ level of effort expended in four primary ways: 1) a reduction in CHW visits, 2) a reduction in quality of care, 3) CHW attrition, and 4) substitution of other income-generating activities.

Conclusions

This study provides new evidence regarding how removing performance-based financial incentives from a CHW program can negatively impact CHW motivation. The findings suggest that program decision makers should consider how to construct community health work programs such that CHWs may continue to receive performance-based compensation after the original funding ceases.

Keywords: Community health worker, Financial incentives, Motivation, Health workforce, Health systems, Child health

Background

The World Health Organization Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health encourages the use of Community Health Workers (CHWs)—also known as “lay health workers” or “front-line health workers”—as key components of the health workforce, particularly in low- and middle-income countries facing shortages of professional clinicians [1]. A recent World Health Organization guideline defines CHWs as “health workers based in communities, who are either paid or volunteer, who are not professionals, and who have fewer than two years training but at least some training” [2]. While evidence demonstrates that CHWs can cost-effectively deliver high-quality services for a range of health conditions, establishing a successful CHW program requires complicated policy decisions regarding issues such as CHW training, management, and integration within health systems [1, 3–9]. The effectiveness of CHW programs relies heavily on the quality of the CHWs’ relationships with the communities they serve [10, 11]. Since CHW roles have expanded over the past few decades, an increasingly relevant challenge for program decision makers is how to optimize CHW performance without overburdening workers with tasks they lack the time and capacity to perform [12]. Another salient concern is maintaining high levels of CHW motivation [13].

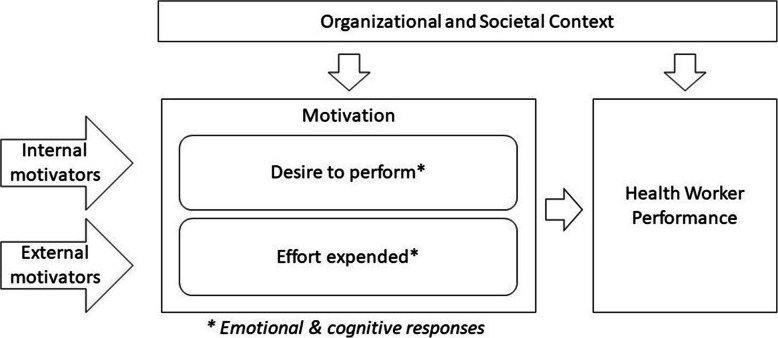

Given the demonstrated association between CHW motivation and performance, questions surrounding CHW motivation have become central to health service quality and program sustainability as CHWs have become increasingly integrated into the global health workforce [11–15]. Figure 1 illustrates our conceptual framework for motivation and CHW performance. At the individual level, motivation can be conceptualized as a multidimensional construct shaped by both internal motivators—e.g., religious beliefs, moral standing, intrinsic values, etc.; and external motivators—e.g. financial incentives, material rewards, social recognition, etc. [13, 16, 17]. How these motivators affect workers depends on individuals’ emotional and cognitive responses (“motivation”), their organizational and societal contexts, and the interaction between these [18].

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Framework for Motivation and Health Worker Performance

Various financial and non-financial compensation mechanisms exist to incentivize CHWs to complete their tasks and responsibilities. Financial rewards may change CHW behavior by influencing two dimensions of motivation: the extent to which workers adopt organizational goals (“desire to perform”) and the extent to which workers effectively work to achieve these goals (“effort expended”) [16, 19–21]. These two closely linked, yet distinct dimensions can exist independently or together. Intrinsic and extrinsic rewards can help maintain high levels of CHW motivation, via their “desire to perform,” by aligning CHWs’ competing interests with optimal job performance [10, 13, 17, 18, 22–27]. Although “effort expended” may also be influenced by rewards, this dimension of motivation is thought to be more heavily influenced by factors such as availability of resources and workers’ perceptions of their competency [18]. While the rich literature on motivation offers multiple ways to conceptualize motivation, “desire to perform” and “effort expended” provided a useful framework to approach this study’s research question.

While some CHW programs provide workers with regular salaries, others rely on a purely volunteer workforce or on various types and combinations of financial and non-financial factors, including intrinsic motivation, to maintain high CHW motivation and performance [13]. Evidence increasingly indicates that financial compensation improves CHW performance and retention [1, 10–13, 28–32]. Non-financial motivators and rewards are also considered important but are not recommended as a substitute for financial compensation [1]. Even in contexts where strong internal motivators are present, CHW motivation may still be buoyed by financial compensation that demonstrates the value of the work and reinforces existing motivation [24].

Compensation for CHWs can take the form of salaries (regular income) and/or performance-based incentives which tie payment to completing certain tasks or meeting certain benchmarks – and each of these may introduce unique challenges. Salaries were previously considered unsustainable in many low- and middle-income countries, although this assumption is recently being challenged [1, 23, 30]. Performance-based financial incentives may crowd out intrinsic motivation, encourage over-reporting of focus tasks, and lead to a substitution effect in which CHWs neglect unpaid tasks in favor of those for which they receive financial compensation [1, 10, 20, 25, 33, 34]. Moreover, performance-based financial incentives may not always be effective motivators if CHWs see them as insufficient, inconsistent, or unpredictable [13, 20, 35].

Although a number of studies have looked at the effects of financial compensation and non-financial motivators on CHW motivation, different circumstances will likely elicit varied responses [29, 32, 36]. Thus, there is still a need for additional empirical evidence in different contexts [10, 13, 23]. Studies on performance-based incentive programs in some settings have shown that withdrawing performance-based financial incentives can decrease health worker motivation, job attendance, and quality of care [37, 38], yet the evidence is particularly limited regarding the effects of removing performance-based financial incentives after introducing them to existing CHW programs in low-resource settings. This study addresses this gap by exploring how the removal of performance-based financial incentives was perceived to impact CHW motivation after formal funding ceased for an infant and young child feeding (IYCF) program in Bangladesh. A secondary research question looks at how inherent non-financial motivators (e.g., religious beliefs, values, social recognition, etc.) affected CHW motivation after financial incentives were removed.

Methods

Study context: Alive & Thrive Initiative in Bangladesh

The Alive & Thrive initiative (A&T) was a multi-component IYCF program implemented between 2009 and 2014 in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Vietnam, and funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation [39]. In Bangladesh, nationwide prevalence of stunting among children under 5 years was 36% in 2014 [40]. Child undernutrition in Bangladesh remains largely attributable to inadequate IYCF behaviors [41]. As one of four main A&T program components designed to improve IYCF practices in Bangladesh, interpersonal counseling services were delivered by the nongovernmental organization BRAC and its networks of nonpaid volunteer CHWs and paid health workers [42–44]. Volunteer CHWs included both Shasthya Shebikas (general community health volunteers) and Pushti Shebikas (community health volunteers working exclusively in IYCF) who worked in their home communities, and paid health workers included Shasthya Kormis (general paid health workers) and Pushti Kormis (paid health workers working exclusively in IYCF) who covered a larger area than the volunteer workers [35, 45–47]. Prior to A&T, the general community health volunteers delivered health education messages about breastfeeding as part of the standard service package within BRAC’s Essential Health Care Program [45]. Upon initiation of A&T, the IYCF-focused community health volunteers and IYCF-focused paid health workers were introduced in areas not covered by existing general community health volunteers and general paid health workers, to strengthen IYCF services. During A&T, the volunteer CHWs began receiving performance-based financial incentives (6 to 8 USD per month compared to a mean monthly household expenditure of about 106 USD) and additional training to deliver enhanced messages, personalized counseling, and hands-on support related to early and exclusive breastfeeding and appropriate complementary feeding practices [45, 48, 49].

A cluster-randomized program evaluation demonstrated that A&T’s combined approach in Bangladesh increased exclusive breastfeeding by 36.2 percentage points, early initiation of breastfeeding by 16.7 percentage points, and minimum dietary diversity by 16.3 percentage points [43, 50]. When A&T ended in December 2014, project support ceased for IYCF-specific financial incentives, refresher trainings, or job aids, although BRAC still expected IYCF counseling and education services to continue. While some A&T program activities and benefits continued, other activities, such as training and reporting, ceased altogether or experienced a substantial attenuation in implementation [51]. For example, 2 years after A&T ended, exposure to volunteer CHWs for interpersonal counseling was higher in intensive intervention areas than comparison areas; however, it had still experienced a decrease from 87.4% to 59.3% in intervention areas [44]. While this decline in program activities is likely a result of multiple factors and complex processes, the objective of the present study is to focus specifically on how the loss of financial incentives contributed to this decline via CHW motivation.

Study sample and data collection

As part of a larger effort to assess the sustainability of A&T in Bangladesh, focus groups were conducted with representatives from multiple sub-districts in which A&T was implemented [51]. Seven districts were purposively selected to achieve geographic variability from a sample of 10 districts that had participated in a previous A&T endline evaluation. Each focus group consisted of male and female BRAC employees from multiple sub-districts within the selected district who were purposively selected because of their experience working as paid supervisors of CHWs tasked with delivering IYCF services. The focus groups were held with supervisors because an objective was to collect data on managerial-level insights on program implementation, and supervisors were likely to provide a program-level perspective that is broader than the views of individual CHWs. The research team initially planned for seven focus groups but created a contingency plan for additional focus groups if data saturation was not reached. All participants were a minimum of 18 years of age and provided verbal consent to participate in the study.

A semi-structured focus group discussion guide was developed by the research team and used to elicit perspectives from BRAC employees about the perceived impact of removing A&T financial incentives from volunteer CHWs as well as on other post-implementation related programmatic issues (e.g., implementation challenges, continuation of activities, adaptations, funding, human resources, and quality of services). The guide was developed in English, and after an iterative revision process, translated into Bengali.

Focus group discussions occurred between January–May 2017, 2 years after A&T program support ceased, and were conducted in Bengali by experienced male and female facilitators who received specific training about this study. The focus group facilitators had academic training in qualitative research and the social sciences and were employed as full time researchers at the time of the study. After receiving approval from BRAC to organize the focus groups, the research team contacted the participants via email to explain the study and invite them to participate in the focus group. Participants received informed consent forms with information about the study purposes, methods, and privacy. All focus groups were audio recorded with permission from participants. A designated note taker made field notes during the discussions. Focus groups occurred in training rooms at the local BRAC offices and lasted between 90 and 160 min. This study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, University of California Los Angeles, and icddr,b in Bangladesh.

Data analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim, and the transcripts were translated into English before being uploaded to NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12, 2018). The codebook was developed using a combination of inductive and deductive techniques. Two parallel components of health worker motivation—“desire to perform” and “effort expended”—were themes identified a priori, which helped to identify sub-themes on the impacts of removing financial incentives and CHW motivation [16, 19, 20]. The research team used a deductive approach to identify emergent themes [52] based on participants’ responses that explicitly mention how they viewed the relationship between incentives and CHW motivation, including types of non-financial motivators identified in prior CHW studies [10, 13]. Emergent codes were discussed and defined to generate a final codebook. Two researchers used the final codebook to independently code all of the transcripts. Coding discrepancies and preliminary findings were iteratively discussed by the research team to achieve consensus.

Results

Seven focus groups were conducted across seven districts (n = 43 respondents; group size range: 6–7 participants). Participants (see Table 1) included both men and women between the ages of 24 and 36 years. All participants had a master’s degree and between 2 and 6 years of work experience in their roles as CHW supervisors, meaning that they all had experience working on A&T implementation before the project ended.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Focus Group Participants

| Total N of Participants | 43 |

| N Male | 32 |

| N Female | 11 |

| Mean Age in Years (range) | 33.1 (24–37) |

| Mean Years of Experience (range) | 4.7 (2–6) |

| Master’s Degree | 43 |

According to most respondents, removal of performance-based financial incentives was perceived to have negatively affected volunteer CHW motivation in terms of “desire to perform” and “effort expended” on IYCF-related tasks. Supervisors in all of the focus groups reported observing a direct negative impact on volunteer CHW motivation as a result of removing financial incentives to IYCF tasks. A small number said they had yet to see these effects in their own sub-districts. A respondent in one focus group reported that in one sub-district, volunteer CHWs were still receiving small performance-based financial incentives from other sources for their IYCF activities, but they had been notified that those incentives would be discontinued at the end of the year. One respondent from a different focus group shared that volunteer CHWs had the expectation that incentives would be paid to them in the near future. Even in these cases, supervisors expected a decrease in motivation once financial incentives completely ceased. Specific types of negative effects and illustrative quotes are included in Table 2. These effects are discussed in more detail below in addition to non-financial motivators. All quotes are from sub-districts in which the incentives had completely ceased.

Table 2.

Key Themes related to the Effects of Removing Performance-Based Financial Incentives on Community Health Workers’ (CHWs) Motivation

| CHWs’ Motivation | Perceived Effect | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Desire to Perform | Decrease in Desire to Work without Financial Compensation | “Incentives must be there; otherwise you cannot get the job done.” |

| Change in Pre- vs Post-Intervention Motivation | “Stopping the incentive after giving them regularly, it is the problem. If the [financial incentive] provision was not there, there might be no trouble.” | |

| Household Income Challenges Due to Dependence on Incentives | “They (the volunteer CHWs) consider this money as salary. They are poor people. ‘Earlier we got 500, 700, 1000 taka. Now [we are] getting 200, 150 taka.’ They told us to take care of this issue, at least if it could stay the same.” | |

| Level of Effort Expended | Reduction in CHW Visits | “Now, the Shebikas (volunteer CHWs) are reducing the visit count due to the reduction on the incentives from the last 2 months.” |

| Perceived Reduction in Quality of Care | “But now, no incentives are given to them. They are not delivering the message properly.” | |

| CHW Attrition | “Now they deliver the messages but do not get any incentives, this is [why] the Shebikas (volunteer CHWs) are dropped out.” | |

| Substitution of Other Income-Generating Activities | “Shebikas (volunteer CHWs) cannot get anything from here (IYCF counseling). They now focus more on nutritious issues (i.e., selling micronutrient powder … There’s a little more work here.” |

Effects of removing performance-based financial incentives on CHWs’ motivation: decreased desire to perform

Respondents reported three primary effects from removing performance-based financial incentives on volunteer CHWs’ desire to perform, namely: 1) a decreased desire to work without financial compensation, 2) changes in pre- and post-intervention motivation, and 3) household income challenges due to dependence on incentives.

The first theme, a decrease in volunteer CHWs’ individual desire to conduct IYCF activities, was discussed in all of the focus groups. While supervisors reported that many CHWs were still conducting IYCF visits, they believed IYCF activities had become a lower priority after the removal of financial incentives, as stated in the following quote: “Health workers are showing their reluctance for the reduction of money.”

Supervisors explained that volunteers CHWs generally no longer wanted to deliver services without financial compensation. In one supervisor’s words, “The mentality [of the] service is coming to people economically. ‘I will not work here without money.’ One will give you one or two days free service. Next time, if you want the service, that person will expect some benefit.”

A second noted effect was a change in volunteers CHWs’ motivation from before A&T introduction to after A&T ceased. As mentioned with the first theme, volunteer CHWs experienced a decreased desire to perform once financial incentives ceased, but beyond that, some supervisors believed introducing and then removing the financial incentives caused volunteer CHWs to have less motivation than they had before the A&T program began. This resulted from an apparent change in volunteer CHW expectations regarding how they felt they should be compensated for IYCF tasks once they began receiving financial incentives—“Whatever we say, budget is involved with it. Earlier, they got honorarium. If I get honorarium once, I will not go there again without honorarium.”

A third effect on volunteer CHWs’ desire to perform consisted of household income dependence on financial incentives during A&T implementation and the resulting income challenges that arose once financial incentives were removed. Over the 5 years of A&T implementation, volunteer CHWs came to see the financial incentives as a vital source of income on which their families depended and to meet their basic needs. Supervisors noted this dependence and the ensuing dissatisfaction among volunteer CHWs once financial incentives were removed.

Supervisors in one focus group discussed how the increased opportunity cost of completing IYCF tasks without financial incentives prevented volunteer CHWs from performing their IYCF counseling responsibilities. One participant explained that if a volunteer CHW is compensated for making an IYCF visit it might be worthwhile for the husband to stay home and take care of the animals and house. However, without a financial incentive for the wife, she would need to stay home so the husband could earn sufficient income for the family to meet their basic needs:

She will … tell her husband that [he does] not need to go to work today. ‘Stay home today. [You] do not need to go to work. You can earn 300 taka. I will get 2000 taka.’ And then she will tell her husband to guard the house. … If [there was] an incentive, then she [would] willingly come here.

Effects of removing performance-based financial incentives on CHWs’ motivation: level of effort expended

While, as described above, changes in the availability of financial incentives affected volunteer CHWs’ level of desire to perform IYCF activities, the focus group data also provides evidence that removing financial incentives directly influenced volunteer CHWs’ level of effort. Respondents reported four negative effects on volunteer CHWs’ level of effort expended, namely: 1) a reduction in volunteer CHW visits, 2) a perceived reduction in quality of care, 3) volunteer CHW attrition, and 4) substitution of other income-generating success of the A&T model relied on volunteer CHWs regularly visiting their communities to provide education and follow-up about IYCF to mothers and pregnant women. Supervisors reported that, after incentives were removed, volunteers CHWs began making less frequent IYCF visits and, in some cases, even stopped conducting IYCF visits at all—“The Shebika (volunteer CHW) who was living around is visiting once [per month]. When there was incentives … the Shebika (volunteer CHW) visited several times [per month] because if they visit then they could get the incentive. This is the impact.”

Due to the volunteer nature of the program, supervisors felt limited in terms of what they could do to ensure the visits. As one supervisor noted, “If the Shebika (volunteer CHW) does not visit, we cannot ask them why they are not going. They are not our salaried staff. If they do not visit we cannot force them. And the Shebika (volunteer CHW) will not visit without any incentives.”

Even when visits continued to be conducted, there was widespread agreement among the supervisors that the quality of services had decreased due to the removal of financial incentives. Supervisors made several similar comments regarding this issue, including “Health workers … have been a little sloppy” and “The Shebika (volunteer CHW) thinks that ‘If the job was a paid one, then I could have done better.’”

Going beyond mere “sloppiness” or not doing the job as well as possible, some supervisors pointed out specific ways they believe the decrease in service quality was impacting IYCF beneficiaries:

They (volunteer CHWs) find out who are the newborn babies because if they can ensure colostrum feeding then she could earn 50 taka as an incentive. … Before she (volunteer CHW) prepared the note [indicating] in which household there is a newborn baby or which mother is ensuring the breastfeed within one hour of birth. … It is known [now] that she is not working properly because she does not get incentive now.

Another supervisor commented, “Maybe a few (volunteer CHWs) are doing, maybe taking the notes about the newborn babies, but due to that less attention, our coverage has already been decreased.”

Supervisors in all but one focus group noted a transfer of responsibility to the paid health workers, who were now being required to take on the work that volunteer CHWs were no longer willing to do—“Since the incentive is stopped or somewhat incentive is less so their (volunteer CHWs’) tendency for working in the field is getting down. The Pushti Kormis (IYCF-focused paid health workers) are doing the tasks of Shebikas (volunteer CHWs).”

The result was a decrease in service quality since the paid health workers were under considerable amounts of pressure and were unable to effectively manage the increased load of both jobs—“Now the Pushti Kormi (IYCF-focused paid health worker) has to find out the pregnant women, the newborn babies of one area, but if the Shebika (volunteer CHW) is paid incentives then she could complete those tasks [to] find out the pregnant mothers and could inform about the newborn babies.”

Additionally since the paid health workers were not village locals, it was much less convenient for them to regularly visit the mothers for counseling and follow-up. One supervisor explained, “Since the Shebika (volunteer CHW) resides in the same area, they can monitor the overall situation, But the Pushti Kormi (IYCF-focused paid health workers) visit once a month.” Another quote further described this effect:

When they drop out then our workforce is reduced, there becomes a gap in between the message delivery, the Pushti Kormi (IYCF-focused paid health workers) cannot deliver the messages while visiting 4-5 days. The Shebika (volunteer CHW) belongs to that village and she will work in that village only, so she can visit every day and there will be no gap in between the times.

The supervisors believed this negatively impacted IYCF service quality:

The health worker (IYCF-focused paid health worker) goes once a month, where the Shebika (volunteer CHW) was staying around the house and because of the incentive, she could not go anymore, which does not go away. There is a difference between telling a mother once and saying repeatedly.

In addition to volunteer CHWs completing fewer visits and delivering lower quality services, supervisors in the majority of focus groups explained that volunteer CHWs were quitting their positions because financial incentives were no longer available. Volunteer CHW attrition was seen to impact IYCF services on a broad scale because of the significant drop in numbers of trained volunteer CHWs—“We stopped giving the incentive in 2016. Now there are 60-65 Shebikas (volunteer CHWs) out of 280 [previously].”

In comparison, attrition had not been identified as a problem during A&T implementation when incentives were available, as one supervisor observed, “Since the incentive was more at that time there were no drop out of Shebikas (volunteer CHWs).”

A final noted effect from removing volunteer CHWs’ financial incentives for IYCF services, and a key reason for the decrease in time dedicated to IYCF services, was that many volunteer CHWs were now dedicating more time to other tasks for which financial incentives are still being offered. For example, supervisors in most focus groups discussed how volunteer CHWs in their sub-districts had shifted from delivering IYCF services to selling nutrition packets (Pushtikona) in order to generate additional income.—“[The] main target is to sell the Pushtikona, so they give less time in demonstrations or other activities. Very little time was given to children aged 0-6 months.” Another supervisor asserted, “They are automatically saying that they will sell more Pushtikona, since they are being paid for that, but they will not give the demo [about complementary feeding], do not find the pregnant women. If we ask them why, then they say that we were not paid in the last month.”

Non-financial motivators and CHW motivation

Some of the focus groups discussed the effects of non-financial motivators on CHW motivation. In this context, these non-financial motivators were not provided deliberately by A&T as performance-based rewards; rather, they were internal and external factors that existed due to the nature of the CHW work within the target communities. However, supervisors described how they used these factors as a strategy to motivate volunteer CHWs to dedicate more effort towards their jobs. In contrast with the financial incentives, these motivators were not discontinued after A&T funding ceased.

When asked about effective strategies to motivate volunteer CHWs, supervisors described how reminding them of the important nature of the task and their community ties could have an impact:

We say “If the mother does not do the exclusive breast feeding till 6 months then it will harm the baby who might be your nephew or niece, may be your cousin’s brother or cousin’s sister. If you do this small help to them, the mother will pray for you. At least continue this sacred task, after that whenever we will get the money we will provide it from office.”

Another supervisor remarked, “Convince and motivate them by saying that this is a work for humanity by which your acceptance to the people will increase.” As noted in the previous comment, social recognition was another non-financial motivator that supervisors believed was helping to maintain motivation and drive performance among some volunteer CHWs who continued to work diligently after the removal of the financial incentives. A supervisor explained, “Motivation is above all. We tell them that others cannot do what you have done. ‘Although I am more educated than you, I cannot take your position in your area. … All know you by your name.’ I motivate them in all ways.”

Supervisors from multiple groups commented on the importance of recognition within the community: “You are known to the villagers due to the effective service you are providing to them.” and “Shutting down of the incentives is [having] little effect. [Volunteer CHWs] are moving forward on the basis of the popularity that has been working before.”

Supervisors also believed that encouraging volunteer CHWs to feel a sense of responsibility motivated them to continue working without a financial incentive—“She was given [the] responsibility. That way she is doing the job.”

Despite these efforts, some supervisors described how intrinsic motivation alone is insufficient without financial compensation:

How long we should convince them (volunteer CHWs)? If someone tells me that, “You work for BRAC and you will get the chance to achieve the heaven very easily,” I will never work for them. The head office, our superior officers, also know that they have no salary except the incentives, so the Shebikas (volunteer CHWs) should be brought by engaging them by using any strategy with income generating tasks because there is a strong relation between the work and money.

Discussion

Removing performance-based financial incentives from a volunteer CHW program in Bangladesh was perceived to have negative effects on CHW motivation. Similar to findings from previous research, this study demonstrates that CHWs may experience a decreased desire to fulfill their jobs following removal of performance-based financial incentives, and that a major contributing factor was the crowding out of intrinsic motivation [26, 38]. The IYCF program saw decreases in quality of care and number of visits as CHWs dedicated less effort to their jobs and increasingly substituted income-generating activities for IYCF responsibilities after financial incentives were removed [25, 33]. Previous studies conducted among comparable populations of CHWs in Bangladesh similarly found that financial compensation was a strong source of motivation and the main factor associated with CHW retention [31, 53]. The voluntary nature of CHW programs, in addition to other contextual factors, is important, as studies in which performance-based financial incentives were introduced to salaried health workers in different contexts found that incentives had little to no effect on worker motivation [54, 55].

Previous studies on the A&T program in Bangladesh found that performance-based financial incentives were an important element to the program’s success in achieving its IYCF aims. In one analysis, these incentives were directly associated with improved quantity and quality of IYCF service delivery [56]. Other impact evaluations of the A&T program found that an intensive IYCF intervention package that included performance-based financial incentives had significant positive impacts on breastfeeding practices, maternal nutrition among pregnant women, and child development compared to a nonintensive intervention package that did not include financial incentives [43, 57, 58]. Our finding that CHWs experienced a decrease in motivation post-incentive removal bolsters the conclusion of a separate study on the A&T program in Bangladesh that the removal of cash incentives was likely a contributing factor to reduced program exposure and impact after program funding ceased [44]. However, it is critical to note that the negative effect of removing financial incentives on CHW motivation may be only one of many contributing factors that affected IYCF service delivery in A&T intervention areas after the program ceased. Attributing a specific effect size to financial incentive removal in comparison with other factors is beyond the scope of this qualitative analysis.

Although the main findings are consistent with existing studies, our qualitative data highlights perceived effects of removing incentives that are less prominent in the CHW literature. First, some supervisors believed that CHW motivation was lower following removal of the performance-based financial incentives than it was prior to the introduction of incentives at program onset. While this perspective was mentioned only occasionally and was not explored in depth during the focus groups, if true, this finding has important sustainability implications for global health programs considering introducing performance-based financial incentives where they do not currently exist. This new financial compensation structure could potentially undermine existing non-financial motivational mechanisms for CHWs, including a commitment to serve their local communities.

Programs must consider how volunteer CHWs may be uniquely affected by performance-based incentives as these represent the sole source of financial compensation for their work. Given that the volunteer CHWs had grown dependent on IYCF financial incentives as a vital source of income, removing the incentives could have affected various aspects of their lives and well-being—creating a sense of dissatisfaction with the available incentives with which an accompanying decrease in motivation would be expected [11, 12]. Not only did CHWs lose the ability to purchase food or pay for school supplies, but they were also forced to adjust familial roles—i.e., breadwinner vs homemaker—to make up for female CHWs’ lost income. In such cases, the reduction in CHW visits may be due less to a lack of desire to perform and possibly due to the practical realities of meeting a family’s basic needs. This finding reinforces the idea that financial remuneration is even more critical in high-poverty areas in order to reach a point at which intrinsic motivation can also play a role [20, 26]. Of course, the magnitude of the financial incentive relative to household expenditure is an important factor in determining the effects of withdrawing the incentive. In Bangladesh, the mean monthly household expenditure in the A&T intervention areas was around 9000 taka (106 USD), and the monthly incentive for CHWs typically totaled between 500 and 700 taka (6 to 8 USD) [48, 49]. We expect that withdrawing a financial incentive that represents a larger percentage of household expenditure than this would be more demotivating for CHWs and more disruptive to familial roles.

Finally, in some sub-districts CHWs continued IYCF activities despite no longer receiving financial compensation. This suggests not a ‘crowding out’ but a ‘crowding in’ of intrinsic motivation, which may be more likely to occur in programs where CHWs feel more support—e.g., training, encouragement—from their supervisors and more confident in their own abilities [24]. Although this study was unable to assess levels of support and confidence among those CHWs who continued delivering services after A&T financial incentives were removed, supervisors believed that it was unlikely that CHW motivation would remain high without reinstituting financial incentives in some form.

While this qualitative study adds significant understanding to the effects of removing performance-based financial incentives on CHW motivation, there is a need for larger scale, well-designed studies that use mixed-methods research to address the same question. The findings from this study should not be taken as generalizable for other contexts since they focused on a specific IYCF program in a limited number of sub-districts in rural Bangladesh in which A&T had been implemented. This study would have been strengthened by conducting comparison focus groups in non-A&T areas of Bangladesh to explore CHW motivation in similar contexts; future research should also include comparison areas if resources allow. It is particularly important to note that the CHWs in the context of this study were unpaid, and performance-based financial incentives were the only type of financial compensation received. We are therefore unable to disentangle any unique effects that may be attributable to performance-based incentives, versus salaries, as a type of financial compensation. Similarly, cessation of trainings, performance monitoring procedures, and other A&T program features likely affected CHW motivation negatively, yet our data do not allow us to clearly separate the effects of withdrawing financial incentives from the effects of removing other types of support. Thus, our analysis focuses on instances where focus group participants explicitly mention the linkages between financial incentives and our conceptualization of motivation.

CHW supervisors who participated in the focus groups offered unique perspectives and insights, but they do not necessarily represent the actual opinions and perspectives of CHWs. Future research should seek to gather a broader range of perspectives from multiple types of stakeholders. Although the focus group facilitators made deliberate efforts to explain that the study was part of a learning exercise, it is possible that some supervisors’ saw the focus groups as an opportunity to advocate for more program funding, which may have biased their responses. Additional limitations should be considered due to the two-year timeframe that passed between the end of A&T and data collection for this study. It may be that the remaining CHWs were initially more motivated than those who had already left their positions at the time of the focus groups. Recall bias is another important consideration since multiple intervening factors (e.g., groupthink) could have played a role in participants’ views during the intervening period.

Conclusion

Given the prominent role of CHWs in health systems around the world, improving CHW motivation and performance is a critical challenge to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals over the next decade [59]. Both to strengthen motivation and from a human rights and gender equity perspective, regular salaries are a critical element of CHW compensation structures. This study provides new evidence regarding how removing financial compensation from CHW programs can negatively affect CHW motivation. The findings lend support to the argument that, in order to sustain service coverage and quality, focused programs in Bangladesh and in other locations should carefully plan how CHWs will continue receiving compensation after conclusion of the program [38]. Although performance-based financial incentives can improve CHW motivation, these merit careful consideration by CHW project designers due to concerns about sustainability and negative effects. There is a need for more focused, high-quality research on the topic of incentives and motivation in order to explore whether performance-based incentives affect CHW motivation differently if their work is salaried or unpaid.

Acknowledgements

The research team expresses deep gratitude to all who participated in this research including stakeholders, health workers and mothers who provided us with their valuable insights during data collection. Thanks also to the staff at icddr,b who collected data and otherwise supported this work; and to the Alive & Thrive teams (in Washington DC and Dhaka) for their instrumental support and assistance.

Abbreviations

- A&T

Alive and Thrive

- CHW

Community Health Worker

- IYCF

Infant and Young Child Feeding

Authors’ contributions

The overall study and data collection instrument were designed by TJB, MEK and CM, with key inputs from HS and TA. Data collection was coordinated by HS, SKL, MR. Data analysis was led by JG, with support from AC and JS, and leadership from CM and DDP. The first draft of the manuscript was developed by JG, with support from CM, DDP, and AE, and all authors provided substantial inputs and edits. All authors reviewed and approved the final version for submission.

Funding

This research was conducted with support from FHI Solutions LLC, via the Alive & Thrive project which is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the governments of Canada and Ireland. Dr. Payán received salary support during the data collection phase from grant no. T32HS00046 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The funding and implementation agencies were not involved in any aspects of study design, data analysis, or decisions about publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of FHI Solutions LLC, the Alive & Thrive project or its funders.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (protocol #16–1706), University of California Los Angeles (protocol #16–001754), and icddr,b in Bangladesh (Ethical Review Committee, protocol #PR-16060). Participants gave verbal consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the ethics review committees.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [PubMed]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- 3.Rhodes SD, Foley KL, Zometa CS, Bloom FR. Lay health advisor interventions among Hispanics/Latinos. A qualitative systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(5):418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt CW, Grant JS, Appel SJ. An integrative review of community health advisors in type 2 diabetes. J Community Health. 2011;36(5):883–893. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9381-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, Unützer J. Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health Care in Rural and Other low-Resource Settings: a systematic review. J Rural Health. 2018;34(1):48–62. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCollum R, Gomez W, Theobald S, Taegtmeyer M. How equitable are community health worker programmes and which programme features influence equity of community health worker services? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christopher JB, Le May A, Lewin S, et al. Thirty years after Alma-Ata: a systematic review of the impact of community health workers delivering curative interventions against malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea on child mortality and morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-9-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilmore B, McAuliffe E. Effectiveness of community health workers delivering preventive interventions for maternal and child health in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gogia S, Ramji S, Gupta P, Gera T, Shah D, Mathew JL, et al. Community based newborn care: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence: UNICEF-PHFI series on newborn and child health, India. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48(7):537–546. doi: 10.1007/s13312-011-0096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharyya K, LeBan K, Winch P, et al. Community health worker incentives and disincentives: how they affect motivation, retention, and sustainability contributors Karabi. Arlington: World Health Organization; 2001.

- 11.Kok MC, Broerse JEW, Theobald S, Ormel H, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M. Performance of community health workers : situating their intermediary position within complex adaptive health systems. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0234-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, Pariyo G, Rao KD, Cometto G, et al. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0304-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glenton C, Cj C, Carlsen B, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of lay health worker programmes to improve access to maternal and child health : a qualitative evidence synthesis ( review ). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10. 10.1002/14651858.CD010414.pub2.www.cochranelibrary.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Deci EL, Olafsen AH, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science. Annu Rev Organ Psych Organ Behav. 2017;4(1):19–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alhassan RK, Spieker N, van Ostenberg P, Ogink A, Nketiah-Amponsah E, de Wit TFR. Association between health worker motivation and healthcare quality efforts in Ghana. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borghi J, Lohmann J, Dale E, Meheus F, Goudge J, Oboirien K, et al. How to do ( or not to do ) … Measuring health worker motivation in surveys in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(2):192–203. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohmann J, Houlfort N, De Allegri M. Crowding out or no crowding out? A self-determination theory approach to health worker motivation in performance-based financing. Soc Sci Med. 2016;169:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R, Stubblebine P. Determinants and consequences of health worker motivation in hospitals in Jordan and Georgia. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(2):343–355. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00203-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Working together for Health: World Health Report 2006. World Health. 2006;5(1). 10.1186/1471-2458-5-67.

- 20.Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation : a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(8):1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanfer R. Measuring Health Worker Motivation in Developing Countries. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aerts C, Sunyoto T, Tediosi F, et al. The neglected tropical diseases and the neglected infections of poverty: overview of their common features, global disease burden and distribution, new control tool, and process for disease elimination. In: Institute of Medicine (Ed)et al., editors. The causes and impact. In: The Causes and Impacts of Neglected Tropical and Zoonotic Diseases: Opportunities for Integrated Intervention Strategies. 2017. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal S, Kirk K, Sripad P, Bellows B, Abuya T, Warren C. Setting the global research agenda for community health systems: literature and consultative review. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12960-019-0362-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenspan JA, Mcmahon SA, Chebet JJ, et al. Sources of community health worker motivation : a qualitative study in Morogoro Region , Tanzania. Hum Resour Health. 2013;1(1). 10.1186/1478-4491-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Kok MC, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M, et al. Which intervention design factors influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries ? A systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2015:1207–27. 10.1093/heapol/czu126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Vareilles G, Pommier J, Marchal B, Kane S. Understanding the performance of community health volunteers involved in the delivery of health programmes in underserved areas : a realist synthesis. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0554-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kigozi G, Heunis C, Engelbrecht M. Community health worker motivation to perform systematic household contact tuberculosis investigation in a high burden metropolitan district in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):882. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05612-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherrington A, Ayala GX, Elder JP, et al. Recognizing the diverse roles of community health workers in the elimination of health disparities: from paid staff to volunteers. Ethn Dis. 2010;20:189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willis-shattuck M, Bidwell P, Thomas S, et al. Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries : a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1). 10.1186/1472-6963-8-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Khan MS, Mehboob N, Rahman-Shepherd A, Naureen F, Rashid A, Buzdar N, et al. What can motivate lady health Workers in Pakistan to engage more actively in tuberculosis case-finding? BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7326-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh D, Negin J, Otim M, Orach CG, Cumming R. The effect of payment and incentives on motivation and focus of community health workers: five case studies from low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0051-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Celhay PA, Gertler PJ, Giovagnoli P, Vermeersch C. Long-run effects of temporary incentives on medical care productivity. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2019;11(3):92–127. doi: 10.1257/app.20170128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glenton C, Scheel IB, Pradhan S, Lewin S, Hodgins S, Shrestha V. The female community health volunteer programme in Nepal: decision makers’ perceptions of volunteerism, payment and other incentives. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(12):1920–1927. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmstrom B, Milgrom P. The Economic Nature of the Firm: A Reader, Third Edition. 2012. Multitask principal–agent analyses: Incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarma H, Jabeen I, Luies SK, Uddin MF, Ahmed T, Bossert TJ, et al. Performance of volunteer community health workers in implementing home-fortification interventions in Bangladesh: a qualitative investigation. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frey BS, Jegen R. Motivation crowding theory. J Econ Surv. 2001;15(5):589–611. doi: 10.1111/1467-6419.00150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minchin M, Roland M, Richardson J, Rowark S, Guthrie B. Quality of care in the United Kingdom after removal of financial incentives. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(10):948–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1801495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huillery E, Seban J. Pay-for-performance, motivation and final output in the health sector: experimental evidence from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Sci Po Econ Discuss Paper 2014-12. https://spire.sciencespo.fr/hdl:/2441/4pmvo3bm7m9claao2gl0337ip4/resources/2014-12.pdf.

- 39.Alive and Thrive . Framework for delivering nutrition results at scale: The Alive & Thrive Initiative. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nisbett N, Davis P, Yosef S, Akhtar N. Bangladesh’s story of change in nutrition: strong improvements in basic and underlying determinants with an unfinished agenda for direct community level support. Glob Food Sec. 2017;13:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.USAID . Bangladesh: Nutrition Profile. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Epstein A, Moucheraud C, Sarma H, Rahman M, Tariqujjaman M, Ahmed T, et al. Does health worker performance affect clients’ health behaviors? A multilevel analysis from Bangladesh. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4205-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Menon P, Nguyen PH, Saha KK, Khaled A, Kennedy A, Tran LM, et al. Impacts on breastfeeding practices of at-scale strategies that combine intensive interpersonal counseling, mass media, and community mobilization: results of cluster-randomized program evaluations in Bangladesh and Viet Nam. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim SS, Nguyen PH, Tran LM, Sanghvi T, Mahmud Z, Haque MR, et al. Large-scale social and behavior change communication interventions have sustained impacts on infant and young child feeding knowledge and practices: results of a 2-year follow-up study in Bangladesh. J Nutr. 2018;148(10):1605–1614. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanghvi T, Martin L, Hajeebhoy N, Abrha TH, Abebe Y, Haque R, et al. Strengthening systems to support mothers in infant and young child feeding at scale. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34(3_suppl2):S156–S168. doi: 10.1177/15648265130343s203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.USAID . Case Studies of Large-Scale Community Health Worker Programs: Examples from Afghanistan, Bangladesh,Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Iran, Nepal, Niger, Pakistan, Rwanda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. 2017. Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarma H, Tariqujjaman M, Mbuya MNN, Askari S, Banwell C, Bossert TJ, et al. Factors associated with home visits by volunteer community health workers to implement a home-fortification intervention in Bangladesh: a multilevel analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2020;24(S1):s23–s36. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019003768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saha K, Bamezai A, Khaled A, et al. Alive & thrive baseline survey report: Bangladesh. Washington, D.C: World Health Organization; 2011.

- 49.Sanghvi T, Haque R, Roy S, Afsana K, Seidel R, Islam S, et al. Achieving behaviour change at scale: Alive & Thrive’s infant and young child feeding programme in Bangladesh. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12:141–154. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menon P, Nguyen PH, Saha KK, Khaled A, Sanghvi T, Baker J, et al. Combining intensive counseling by frontline workers with a nationwide mass media campaign has large differential impacts on complementary feeding practices but not on child growth: results of a cluster-randomized program evaluation in Bangladesh. J Nutr. 2016;146(10):2075–2084. doi: 10.3945/JN.116.232314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moucheraud C, Sarma H, Ha TTT, Ahmed T, Epstein A, Glenn J, et al. Can complex programs be sustained? A mixed methods sustainability evaluation of a national infant and young child feeding program in Bangladesh and Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09438-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 3. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alam K, Tasneem S, Oliveras E. Retention of female volunteer community health workers in Dhaka urban slums: a case-control study. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(6):477–486. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen GC, Nguyen HTH, Das A, Sachingongu N, Chansa C, Qamruddin J, et al. Incentives to change: effects of performance-based financing on health workers in Zambia. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0179-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dale EM. Performance-based payments, provider motivation and quality of care in Afghanistan. Diss Abstr Int Sect B Sci Eng. 2017.

- 56.Nguyen PH, Kim SS, Tran LM, et al. Intervention Design Elements Are Associated with Frontline Health Workers’ Performance to Deliver Infant and Young Child Nutrition Services in Bangladesh and Vietnam. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3:nzz070. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frongillo EA, Nguyen PH, Saha KK, Sanghvi T, Afsana K, Haque R, et al. Large-scale behavior-change initiative for infant and young child feeding advanced language and motor development in a cluster-randomized program evaluation in Bangladesh. J Nutr. 2017;147(2):256–263. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.240861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen PH, Kim SS, Sanghvi T, Mahmud Z, Tran LM, Shabnam S, et al. Integrating nutrition interventions into an existing maternal, neonatal, and child health program increased maternal dietary diversity, micronutrient intake, and exclusive breastfeeding practices in Bangladesh: results of a cluster-randomized program Eval. J Nutr. 2017;147(12):2326–2337. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.257303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rowe AK, Labadie G, Jackson D, Vivas-Torrealba C, Simon J. Improving health worker performance: an ongoing challenge for meeting the sustainable development goals. BMJ. 2018;362:k2813. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.