Abstract

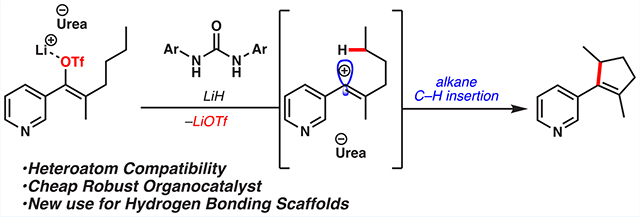

Herein we report the 3,5-bistrifluoromethylphenyl urea-catalyzed functionalization of unactivated C–H bonds. In this system, the urea catalyst mediates the formation of high-energy vinyl carbocations that undergo facile C–H insertion and Friedel–Crafts reactions. We introduce a new paradigm for these privileged scaffolds where the combination of hydrogen-bonding motifs and strong bases affords highly active Lewis acid catalysts capable of ionizing strong C–O bonds. Despite the highly Lewis-acidic nature of these catalysts that enables triflate abstraction from sp2 carbons, these newly found reaction conditions allow for the formation of heterocycles and tolerate highly Lewis-basic heteroaromatic substrates. This strategy showcases the potential utility of dicoordinated vinyl carbocations in organic synthesis.

Graphical Abstract

As evidenced by the elegant and pervasive metal carbenoid chemistry in the literature, forging C–C bonds via C–H insertion reactions is a powerful strategy in organic synthesis.1,2 Here the transition metal tempers the highly reactive nature of the neutral dicoordinate carbon center, facilitating selective and controlled reactivity. Recently, our group has shown that vinyl carbocations can participate in C–H insertion reactions that are mechanistically complementary to classical carbenoid insertion chemistry.3,4 Whereas previous studies from our group and others have demonstrated that these species undergo facile C–C bond-forming reactions, all catalytic systems reported thus far have utilized expensive, hygroscopic, and specialized weakly coordinating anion (WCA) salts that are often difficult to functionalize and establish structure–function relationships (Figure 1a).5

Figure 1.

Vinyl cation insertion reactions and hydrogen-bond donor catalysts. (a) Lithium-promoted intramolecular C–H insertion reactions of vinyl cations. (b) Chiral thiourea-catalyzed additions to oxocarbenium cations via chloride abstraction. (c) Functionalization of unactivated C–H bonds catalyzed by ureas.

In an effort to identify more easily accessible and modular catalysts for these powerful transformations, we looked toward hydrogen-bonding catalysts, such as thioureas. These readily available and highly tunable scaffolds have found success in promoting the formation of cationic intermediates.6,7 Specifically, we were inspired by Reisman and Jacobsen’s use of thioureas to generate resonance-stabilized tricoordinate carbocations that engage in highly selective bond-forming processes (Figure 1b).8 The same group later showed that squaramides, combined with trimethylsilyl triflate (TMSOTf), enhance the electrophilicity of the silicon center via triflate binding.9 Inspired by these studies, we sought to apply an analogous mode of ionization to vinyl triflates, which would provide vinyl cations capable of C–C bond-forming reactions. Herein we report the successful realization of this hypothesis where the combination of urea scaffolds and Li bases catalyzes C–H functionalization and Friedel–Crafts reactions through intermediate vinyl cations (Figure 1c).

We began proof-of-concept studies in the context of the C–H insertion reactions of propylated benzosuberonyl triflate 1 (Table 1).5 We hypothesized that a hydrogen-bonding catalyst could ionize its vinyl triflate, and the ensuing vinyl carbocation would insert into the terminal CH3 group of the tethered propyl chain to give product 2. Initially, the use of Schreiner’s thiourea 3 gave neither conversion to the desired product 2 nor consumption of starting material 1. We rationalized that a stronger Lewis acid was needed to promote the ionization. On the basis of our previous studies, we hypothesized that deprotonation of the urea would yield a lithiated species sufficiently Lewis-acidic to ionize an enol triflate, revealing the potent vinyl carbocation.5,10,11 To our delight, we found that the addition of a stoichiometric amount of lithium hexamethyldisilazide (LiHMDS) to this reaction mixture resulted in a high-yielding C–H insertion reaction, giving tricycle 2 in 78% yield (entry 2). The urea and squaramide analogs (4 and 5, respectively) of Schreiner’s catalyst were also competent catalysts for this transformation, yielding the desired product in 96 and 72% yield, respectively (entries 3 and 4). This catalytic system was also effective at lower temperatures and with lower equivalents of base (entries 5 and 6). Performing the reaction without any urea catalyst (4) yielded negligible amounts of desired product (entry 7). These experiments showcase the necessity of both the hydrogen-bonding catalyst and the lithium base. Additionally, performing this reaction with catalytic lithiated urea 4-Li gave the desired product in 86% yield, suggesting that this is on, or accessible through, the active catalytic cycle (entry 8). Having found that urea catalyst 4 afforded the desired product in the highest yield, we next explored the effect of catalyst substitution on the product outcome. Probing monosubstituted trifluoromethyl urea catalysts (6–8) revealed the importance of a meta-trifluoromethyl group (79% yield for entry 10 vs 3–9% yield for entries 9 and 11).12 Lastly, the N-methylated catalyst 9 delivered the desired product in a meager 19% yield, highlighting the importance of having both N–H hydrogen-bond donors (entry 12).

Table 1.

Optimization of C–H Insertion Reactions with Hydrogen-Bonding Catalysts

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | catalyst | LiHMDS equiv | temp (°C) | yield (%) |

| 1 | 3 | none | 30 | 0 |

| 2 | 3 | 1.5 | 30 | 78 |

| 3 | 4 | 1.5 | 30 | 96 |

| 4 | 5 | 1.5 | 30 | 72 |

| 5 | 4 | 1.5 | −40 | 93 |

| 6 | 4 | 1.2 | 30 | 96 |

| 7 | none | 1.2 | 30 | 3 |

| 8 | 4-Li | 1.2 | 30 | 86 |

| 9 | 6 | 1.2 | 30 | 3 |

| 10 | 7 | 1.2 | 30 | 79 |

| 11 | 8 | 1.2 | 30 | 9 |

| 12 | 9 | 1.2 | 30 | 19 |

| ||||

To further develop the scope of this reaction, urea-catalyzed Friedel–Crafts reactions of vinyl triflates were explored. Here we decided to use the optimized reaction conditions from the above insertion chemistry as a starting point. We found a large scope of both triflates and arenes to be tolerant of this transformation. A silylated pyrrole gave moderate selectivity for vinylation of the C3 position (Figure 2a, 10).13 Electron-deficient vinyl triflates were tolerated, reacting with anisoles and xylenes in moderate to good yields (52–76%, 11–13). The trifluoromethylated vinyl triflate also reacted with benzene or a bromobenzene derivative, yielding vinylated arenes in high yields (14 and 15). More electron-rich aromatic nucleophiles, such as dimethoxybenzene, underwent smooth coupling with a variety of halogenated vinyl triflates in good yields (16–18). There was a minimal decrease in efficiency when performing the reaction on a 1 g scale with the iodinated vinyl triflate, giving styrene 18 in 64% yield. Furthermore, cyclooctenyl triflate 19 was observed to undergo a transannular C–H insertion, Friedel–Crafts cascade with 4-methylanisole, giving alkylated arene 20 in 57% yield (Figure 2b). Here two C–C bonds, a 5,5-fused ring system, and a quaternary carbon center were all forged in a single step. Notably, all of the reactions outlined in Figure 2 were performed on the bench and required neither scrupulous drying of substrates nor catalysts.

Figure 2.

Urea-catalyzed Friedel–Crafts reactions. Isolated yield after column chromatography. (a) Scope of vinyl triflates and arenes. (b) C–H insertion and Friedel–Crafts cascade. a10 equiv of arene. bCatalyst 9. cp-Xylene solvent. dYield determined by gas chromatography with flame-ionization detection (GC-FID).

We then sought to validate our hypothesis that these readily accessible organocatalysts were able to tolerate various functional groups in the context of vinyl cation C–H insertion reactions. To explore the functional group tolerance, a variety of alkylated styrenyl triflates were prepared (Figure 3). We were quite pleased to find that a substrate bearing a pyridine substituent was competent in this transformation, yielding cyclopentenylpyridine 21 in 61% yield. Substrates bearing electron-withdrawing substituents, however, resulted in products with poor olefin isomer ratios.14 Upon further optimization, we discovered that the utilization of LiH allowed for high-yielding reactions with excellent olefin selectivity for these substrates (22–24). Moreover LiOtBu was also a competent base for this transformation, allowing for the formation of dihydrofuran 25 in 61% yield, via insertion into an ether tether. To the best of our knowledge, this example showcases the first heterocycle synthesis from a C–H insertion reaction of a vinyl cation. Furthermore, the variety of Li bases used for these transformations highlights the modularity of this system as well as the importance of both the hydrogen-bonding catalyst and base.

Figure 3.

Urea- and lithium-catalyzed C–H insertion reactions. Isolated yield after column chromatography. aYield determined by NMR using an internal standard. bCatalyst 4. cLiHMDS base in cyclohexane solvent. dCatalyst 5. eLiOtBu base in 1,2-DCE solvent.

Inspired by the successful synthesis of ester 23, we posited that we could also form aryl cyclopentene derivatives via C–H insertion reactions of vinylogous acyl triflates derived from butylated β-ketoester (Figure 4). These substrates are good candidates because they are readily accessible from corresponding β-ketoesters, they would yield highly functionalized cyclopentenes, and they are natively heteroatom-rich, providing a further test of the compatibility of this catalytic system. Under the standard LiHMDS conditions, we found no conversion to the desired product, likely due to the electrophilicity of (vinylogous) esters as well as recent reports describing ester functionalization with LiHMDS.15,16

Figure 4.

Urea-catalyzed C–H insertion reactions of β-ketoester-derived vinyl triflates. Isolated yield after column chromatography. a10 equiv of LiH.

We found that using LiH as the base allowed for productive transformations. Methyl, halogen substituents, boronic esters, and methyl ethers were all tolerated, yielding the ester products 26–29 in 41–64% yield. Notably, under these basic conditions, acid-sensitive functional groups such as a methoxymethyl (MOM) ether-protected phenol or tert-butyl ester remained intact, yielding cyclized products 30 and 31 in 38 and 33% yield, respectively. We observed the exclusive formation of the β,γ-unsaturated products; we attribute this to the increased stability of these products in comparison with the α,β-unsaturated products, likely due to allylic strain.14

With the information derived from our initial scope studies, we began our investigation into the mechanism of this transformation. During our studies of the vinylogous acyl triflates, we consistently noticed small amounts of olefinic products in our crude reaction mixtures. Careful purification of the reaction mixture derived from tolyl triflate 32 provided γ-lactone 33 in 16% yield (Figure 5a). We attribute the formation of this byproduct to the intermediate vinyl cation 34 undergoing a 1,5-hydride shift, generating secondary carbocation 35. This putative intermediate can then undergo a facile 1,2-hydride shift to yield secondary carbocation 36 followed by trapping by the pendant ester, yielding the lactone product. This overall “rebound”-type mechanism has been proposed by Stang, Hanack, Olah, Mayr, Caple, and others.17 To further support this mechanistic hypothesis, we synthesized propylated triflate 37. Under the reaction conditions, neither the desired insertion product nor lactone byproducts were observed (Figure 5b). We attribute this to the inherent difficulty in the formation of primary carbocation 38. These mechanistic findings stand in stark contrast with those of previously observed vinyl cation C–H insertion reactions of propylated benzosuberonyl triflates (e.g., 1, Table 1) and previously disclosed silylium-mediated transformations that proceed through a concerted C–H insertion process.5 The reason for this mechanistic divergence is unclear at this time.

Figure 5.

Mechanism of urea-promoted C–H insertion. (a) Nature of the C–C bond formation of vinylogous acyl triflates. Ar = p-tolyl. (b,c) Mechanistic studies. (d) Proposed catalytic cycle of reaction. Ar = 3,5-bis(CF3)phenyl.

To investigate if the lithiated urea catalyst was the active Lewis acid, we exposed substrate 32 to a stoichiometric amount of the lithiated urea catalyst, synthesized through the deprotonation of urea 4 with LiHMDS.14 This gave the desired product in 23% yield with LiOTf observed by 7Li and 19F NMR (Figure 5c). On the basis of these results, we propose that the lithiated urea 4-Li is the active species responsible for triflate ionization, although other possibilities such as a dilithiated urea or simply a triflate abstraction by parent urea 4 cannot be ruled out (Figure 5d).5 We posit that the lithiated urea catalyst 4-Li can abstract a triflate from the substrate and produce vinyl cation 40. This can then undergo the C–C bond-forming event, yielding α-ester cation 41 followed by a hydride migration to give benzylic cation 42 and deprotonation to give the product, concurrently forming LiOTf and regenerating the catalyst. In the case of the vinylogous acyl triflate substrates, we posit that C–C bond formation is a stepwise process, proceeding through the pathway outlined in Figure 5a. For the Friedel–Crafts reactions that are performed with LiHMDS, we posit that a similar mechanism is operative.

In conclusion, we disclose a novel application of hydrogen-bonding scaffolds, where 3,5-bistrifluoromethylphenyl ureas catalyze C–C bond-forming reactions of vinyl triflates under strongly basic conditions.18 In the presence of these catalysts, the proposed reactive dicoordinate carbocation intermediates undergo facile C–H insertion and Friedel–Crafts reactions in good to excellent yield. This strategy demonstrates the utility of vinyl carbocation reactions and introduces easily accessible and modular catalysts for these transformations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support for this work was generously provided by the NIH-NIGMS (R35 GM128936), David and Lucile Packard Foundation (to H.M.N.), the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (to H.M.N.), the Pew Charitable Trusts (to H.M.N), and the National Science Foundation (DGE-1650604 to S.P. and B.W.). A.L.B., S.P., and B.W. acknowledge the Christopher S. Foote Fellowship for funding. A.L.B. thanks UCLA for Dissertation Year Fellowship funding. We thank the UCLA Molecular Instrumentation Center for NMR and mass spectroscopy instrumentation as well as the mass spectrometry facility at the University of California, Irvine.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01745.

Experimental procedures, characterization data, and NMR spectra (PDF)

Contributor Information

Alex L. Bagdasarian, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States

Stasik Popov, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Benjamin Wigman, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Wenjing Wei, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Woojin Lee, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

Hosea M. Nelson, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Doyle MP; Duffy R; Ratnikov M; Zhou L Catalytic carbene insertion into C–H bonds. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 704–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) He J; Wasa M; Chan KSL; Shao Q; Yu J-Q Palladium-catalyzed transformations of alkyl C–H bonds. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 8754–8786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Davies HML; Du Bois J; Yu J-Q C–H Functionalization in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 1855–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liao K; Pickel TC; Boyarskikh V; Bacsa J; Musaev DG; Davies HML Site-selective and stereoselective functionalization of non-activated tertiary C–H bonds. Nature 2017, 551, 609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liao K; Yang Y-F; Li Y; Sanders JN; Houk KN; Musaev DG; Davies HML Design of catalysts for site-selective and enantioselective functionalization of non-activated primary C–H bonds. Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 1048–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Davies HML; Beckwith REJ Catalytic enantioselective C–H activation by means of metal-carbenoid-induced C–H insertion. Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 2861–2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ma C; Fang P; Mei T-S Recent advances in C–H functionalization using electrochemical transition metal catalysis. ACS Catal 2018, 8, 7179–7189. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wan JP; Gan L; Liu Y Transition metal-catalyzed C–H bond functionalization in multicomponent reactions: a tool toward molecular diversity. Org. Biomol. Chem 2017, 15, 9031–9043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Shao B; Bagdasarian AL; Popov S; Nelson HM Arylation of hydrocarbons enabled by organosilicon reagents and weakly coordinating anions. Science 2017, 355, 1403–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Popov S; Shao B; Bagdasarian AL; Benton TR; Zou L; yang Z; Houk KN; Nelson HM Teaching an old carbocation new tricks: intermolecular C–H insertion reactions of vinyl cations. Science 2018, 361, 381–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wigman B; Popov S; Bagdasarian AL; Shao B; Benton TR; Williams CG; Fisher SP; Lavallo V; Houk KN; Nelson HM Vinyl carbocations generated under basic conditions and their intramolecular C–H insertion reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 9140–9144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Doyle AG; Jacobsen EN Small-molecule H-bond donors in asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Rev 2007, 107, 5713–5743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schreiner PR; Wittkopp A Org. Lett 2002, 4, 217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kotke M; Schreiner PR Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 434–439. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Knowles RR; Jacobsen EN Attractive noncovalent interactions in asymmetric catalysis: links between enzymes and small molecule catalysts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2010, 107, 20678–20685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Reisman SE; Doyle AG; Jacobsen EN Enantioselective thiourea-catalyzed additions to oxocarbenium ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 7198–7199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Banik SM; Levina A; Hyde AM; Jacobsen EN Lewis acid enhancement by hydrogen-bond donors for asymmetric catalysis. Science 2017, 358, 761–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jakab G; Tancon C; Zhang Z; Lippert KM; Schreiner PR (Thio)urea organocatalysts equilibrium acidities in DMSO. Org. Lett 2012, 14, 1724–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ni X; Li X; Wang Z; Cheng J-P Squaramide equilibrium acidities in DMSO. Org. Lett 2014, 16, 1786–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Lippert KM; Hof K; Gerbig D; Ley D; Hausmann H; Guenther S; Schreiner PR Eur. J. Org. Chem 2012, 2012, 5919–5927. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Simchen G; Majchrzak MW Friedel-Crafts acylation of 1-tert-butyldimethylsilylpyrrole, a very short and simple route to 3-substituted pyrroles. Tetrahedron Lett 1985, 26, 5035–5036. [Google Scholar]

- (14). See the Supporting Information for details.

- (15).Li G; Szostak M Highly selective transition-metal-free transamidation of amides and amidation of esters at room temperature. Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Li G; Ji C-L; Hong X; Szostak M Highly chemoselective, transition-metal-free transamidation of unactivated amides and direct amidation of alkyl esters by N–C/O–C cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 11161–11172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Hargrove RJ; Stang PJ Solvolysis of medium ring size cycloalkenyl triflates: a comparison of relative rates vs ring size. Tetrahedron 1976, 32, 37–41. [Google Scholar]; (b) Olah GA; Mayr H Stable carbocations. 198. Formation of allyl cations via protonation of alkynes in magic acid solution. Evidence for 1,2-hydrogen and alkyl shifts in the intermediate vinyl carbocations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1976, 98, 7333–7340. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kanishchev MI; Shegolev AA; Smit WA; Caple R; Kelner MJ 1,5-hydride shifts in vinyl cation intermediates produced upon the acylation of acetylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1979, 101, 5660–5671. [Google Scholar]; (d) Lamparter E; Hanack M Vinyl-kationen, VI solvolyse von 1-cyclononenyl- und 1-cyclodecenyl-trifluormethansulfonat. Chem. Ber 1972, 105, 3789–3793. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bagdasarian AL; Popov S; Wigman B; Wei W; Lee W; Nelson HM Urea-Catalyzed Functionalization of Unactivated C–H Bonds. ChemRxiv 2020, DOI: 10.26434/chemrxiv.11886789.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.