Abstract

Objective

Health care delivery systems transformed rapidly at the beginning of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic to slow the spread of the virus while identifying novel methods for providing care. In many ways, the pandemic affected both persons with neurologic illness and neurologists. This study describes the perspectives and experiences of community neurologists providing care for patients with neurodegenerative illnesses during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative study with 20 community neurologists from a multisite comparative-effectiveness trial of outpatient palliative care from July 23, 2020, to November 11, 2020. Participants were interviewed individually about the impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on their professional and personal lives. Interviews were analyzed with matrix analysis to identify key themes.

Results

Four main themes illustrated the impact of the pandemic on community neurologists: (1) challenges of the current political climate, (2) lack of support for new models of care, (3) being on the frontline of suffering, and (4) clinician self-care. Taken together, the themes capture the unusual environment in which community neurologists practice, the lack of clinician trust among some patients, patient and professional isolation, and opportunities to support quality care delivery.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic and pandemic politics created an environment that made care provision challenging for community neurologists. Efforts to improve care delivery should proactively work to reduce clinician burnout while incorporating support for new models of care adopted due to the pandemic.

Trial Registration Information

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03076671.

Once the first known case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was identified in the United States, health care delivery rapidly transformed to help slow the spread of cases.1 Hospitals and health care systems adopted World Health Organization and Institute of Medicine guidelines and implemented strategies to control infection rates.2,3 Neurologists rose to the challenge and quickly adapted to this new environment.4,5 Many neurologists adjusted their practices to safely continue to provide care for patients while health care systems increased their reliance on telemedicine as an alternative to in-person ambulatory services. These measures were meant to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 while improving access to care for patients.6

However, the rapid changes in health care systems created by the pandemic may place clinicians at risk for greater clinician burnout with heavier workloads. In addition, for those continuing to provide in-person care, clinicians were at increased risk of catching COVID-19 due to shortages of personal protective equipment.7 Moreover, there is added stress for clinicians caring for patients living with neurodegenerative conditions, who tend to be older and more vulnerable to infection and to potentially have greater difficulties with social distancing and digital connection.8 In addition, clinicians are practicing in an era when misinformation instead of evidence-based medicine may be shaping the behavior of the general public.9,10

Little is known about how neurologists providing care for patients living with neurodegenerative illnesses in the United States are navigating the challenges of COVID-19 or the impact of the pandemic on clinicians' professional and personal lives. While there has been some research describing factors influencing excessive burnout experienced by neurologists,11 it remains unclear whether and how the COVID-19 pandemic influences burnout. The objective of this study was to understand the perspectives and experiences of community-based neurologists involved in providing care for patients with neurodegenerative disease under pandemic conditions.

Methods

Study Design

This qualitative descriptive study was part of a large multisite, randomized clinical trial of community-based, integrated, outpatient palliative care for patients with Parkinson disease and related disorders.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site. The parent study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the clinical trial identifier NCT03076671. All participants provided informed consent.

Participants

Clinicians were enrolled in the trial if they provided care for patients with Parkinson disease and related disorders, were willing to refer a minimum of 6 patients per year over 3.5 years of the study enrollment, were willing to receive additional palliative care clinical training in the form of an 8-hour didactic session, and were willing and able to commit to study procedures. Qualitative interviews were conducted with participants who had participated in the 8-hour palliative care didactic sessions. Clinicians were excluded if they had a primary appointment within an academic medical institution.

Interviews with 20 neurologists were held between July 23, 2020, and November 11, 2020. Attempted contact was made to all 29 actively participating clinicians for interviews, and 9 did not respond to participate in the qualitative interviews. All participants who agreed to participate were interviewed individually.

Data Collection

A semistructured interview guide focused on clinician experience in the parent study was modified to include COVID-19–focused questions following feedback from other clinician participants. These items included the following: (1) “How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your practice?”;( 2) “How have you seen the COVID-19 pandemic affect the lives of your patients?”; and (3) “How has COVID-19 affected you personally?”

Semistructured interviews lasted between 30 minutes and 1 hour and were conducted remotely by teleconference or by phone with participants using an iterative interview guide. Interviews were conducted one-on-one with participants and 4 authors (R.A., Z.A.M., M.D., and J.J), including a neurologist (Z.A.M.), study coordinator (M.D.) and qualitative methodologists (R.A. and J.J.). Regular meetings to review interview processes and the consistent use of the interview guide ensured consistency in interview style among interviewers. Qualitative study personnel had no prior relationship with the participants. Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. Additional data for demographics and practice characteristics were collected after the initial study enrollment.

Data Analysis

We used a team-based approach to thematic analysis to explore emergent themes regarding the impact of COVID-19 on community neurologists. We used matrix analysis to summarize qualitative data in a table of rows and columns to compare coded data in cells and to observe themes as they emerged.12 Our matrix analysis was guided by the 3 core questions that were asked of clinicians. Three qualitative team members (R.A., M.D., Z.M.) independently read transcripts and triple-coded a portion of transcripts to ensure coding consistency. Coding consistency checks were also made throughout the coding phase, and discrepancies were resolved by team discussion.13 Themes were developed inductively through qualitative team members’ independent coding of each interview transcript, categorizing emerging themes, and discussing the most salient themes as a group until saturation was reached. This iterative process continued until no new themes emerged and there was agreement between team members about emergent themes. Analyses continued with emergent themes, categories, and conclusions and were discussed consistently with the larger study team.14

Data Availability

Anonymized data are available and will be shared on reasonable request from any qualified investigator.

Results

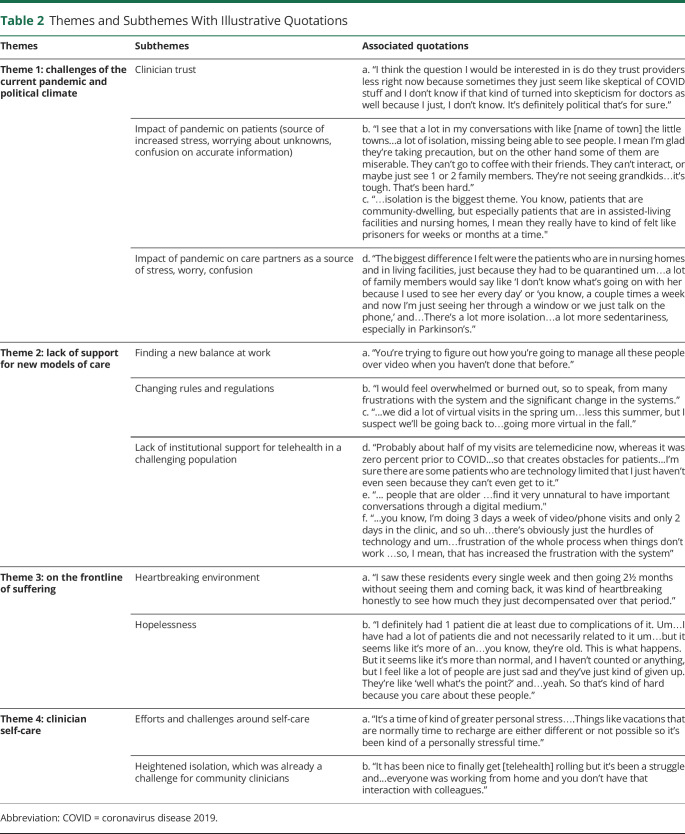

We conducted a total of 20 interviews with community neurologists. Participant characteristics, including demographics and practice environment, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participating Clinician Characteristics

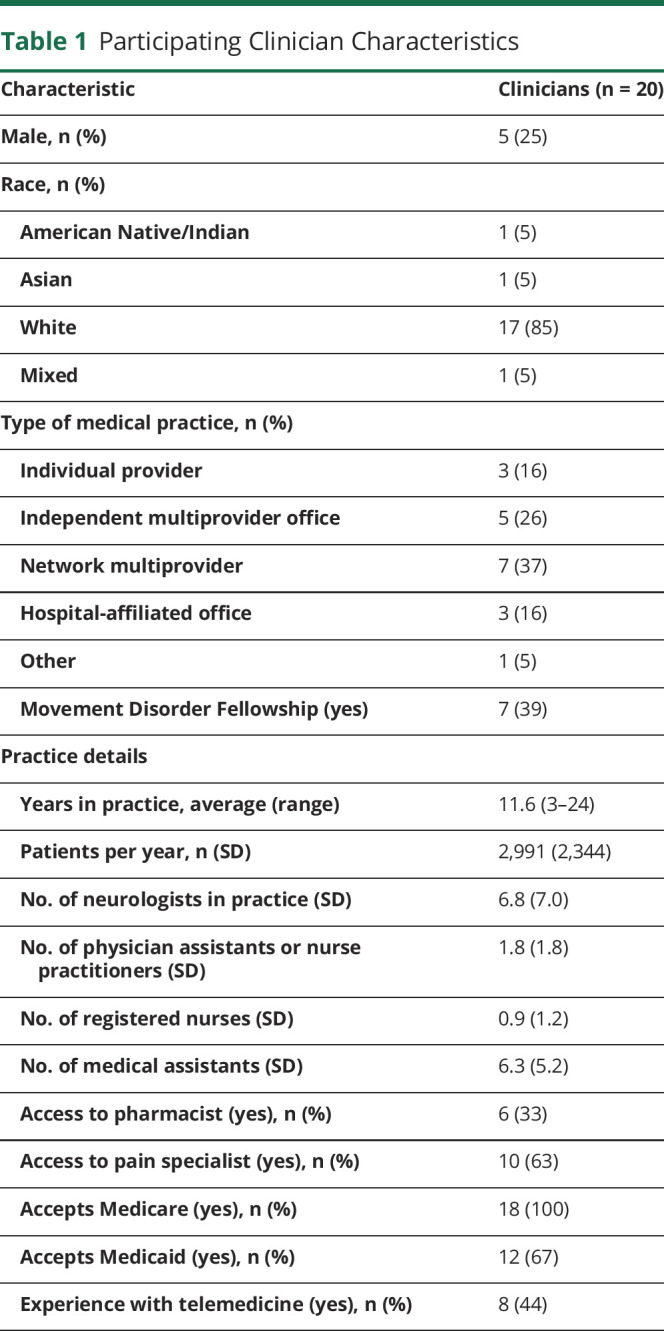

Overall, participants described 4 main themes associated with their experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. These themes are (1) challenges of the current pandemic and political climate; (2) lack of support for new models of care; (3) being on the frontline of suffering; and (4) clinician self-care. Overall, the themes capture the unprecedented circumstances in which community neurologists are practicing, including a lack of clinician trust among some patients, patient and professional isolation, and opportunities for additional support for quality care delivery. Table 2 presents illustrative quotations for each theme and related subtheme associated with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on community neurologists.

Table 2.

Themes and Subthemes With Illustrative Quotations

Theme 1: Challenges of the Current Pandemic and Political Climate

Community neurologists described observing the intersection of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated politics affecting their practice. They discussed logistical challenges in seeing patients such as reduced clinic hours due to the pandemic. In addition, patient-clinician trust was changing. Participants said they observed the negative impact of the pandemic on patient (physical and mental health) and care partners such as increased burden on care partners, emotional distress, and isolation, which only increased their own stress, worry, and confusion.

Clinician Trust

Clinicians described wavering trust among patients. They connected this to patient skepticism about COVID 19 and the current US political climate negatively affecting patient-clinician trust (Table 2, theme1, quote a).

Impact of Pandemic on Patients (Source of Increased Stress, Worrying About Unknowns, Confusion on Accurate Information)

Clinicians described increased patient stress, worry, and confusion related to the COVID-19 pandemic and its presentation in mainstream and social media. They discussed how social isolation was having a drastic physical and mental impact on patients, making their patients miserable (Table 2, theme 1, quote b). In addition, clinicians felt that some of their patients in assisted-living and nursing home facilities felt like prisoners due to COVID-19 restrictions, which in turn caused extreme isolation and sedentary life, resulting in worse physical and mental outcomes (Table 2, theme 1, quote c).

Impact of Pandemic on Care Partners (Source of Stress, Worry, Confusion)

Clinicians mentioned conversations in which care partners described not knowing details of their loved one's well-being because they lived in nursing homes or assisted-living facilities and were unable to connect as easily or frequently. The uncertainty associated with social distancing in facilities was discussed as a source of stress and anxiety (Table 2, theme 1, quote d).

Lack of Support for New Models of Care

To meet the needs of patients in a pandemic condition, health care systems transformed their delivery approach. This came with new challenges for community neurologists who started rapidly providing care remotely to patients.

Finding a New Balance at Work

Clinicians discussed finding a new balance while practicing medicine in a way in which they were not trained. They needed to adopt new ways of delivering care while in a state of isolation from colleagues and patients (Table 2, theme 2, quote a).

Changing Rules and Regulations

Clinicians highlighted significant changes to their practice environment, creating uncertainty and stress in addition to the ongoing threat of the pandemic. Given the lack of options for deliberate discussions around change, this was especially stressful and unmanageable. The fast development of new protocols to accommodate the pandemic often resulted in new problems that required another round of changes (Table 2, theme 2, quote b).

Some of the changes in the rules and regulations were related to telehealth vs in-person visits for patients, making the working environment uncertain and unstable for clinicians (Table 2, theme 2, quote c).

Lack of Institutional Support for Telehealth in a Challenging Population

Clinicians discussed challenges in navigating the virtual care environment from a patient and an institutional support perspective. They explained that patients were having significant obstacles with virtual care, including challenges in internet connectivity that resulted in patients missing care. This was another challenge dropped in clinicians' laps, without institutional guidance or support for navigating this new virtual care environment (Table 2, theme 2, quote d).

They also described how unnatural it is to have serious conversations with older adults through a screen, making care provision for older adults even more challenging. This was discussed in conjunction with general patient difficulties in navigating the virtual care environment such as Zoom to connect with clinicians (Table 2, theme 2, quote e).

The sum of these changes was frustrating and overwhelming for both clinicians and patients and highlighted the lack of institutional support for the rapid change and novel implementation in care delivery (Table 2, theme 2, quote f).

On the Frontline of Suffering

Clinicians described how social isolation was having a drastic and negative impact on the physical and mental health of patients, leaving clinicians feeling unsettled. They also discussed observing drastic physical and mental decline and hopelessness among their patient population.

Heartbreaking Environment

Clinicians discussed how unsettling and troubling it has been to see their patients quickly deteriorate in an unprecedented amount of time due to the extensive suffering their patients experienced. They talked about how heartbreaking it is to see their patients suffer without the usual care services and family support to help them during these difficult times (Table 2, theme 3, quote a).

Hopelessness

Overall, clinicians described having a challenging time with their patients suffering. As mentioned, providers specifically discussed isolation and negative outcomes among patients in nursing homes and assisted-living facilities. One clinician noted that it felt like more patients had died, possibly because patients had given up (Table 2, theme 3, quote b).

Clinician Self-Care

Clinicians described having less opportunity for self-care, in addition to having more personal and new professional responsibilities due to the pandemic.

Efforts and Challenges Around Self-Care

Clinicians spoke about increased burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic because their usual sources of self-care have been minimized. They discussed how the pandemic caused greater personal stress, yet their ability to go on a vacation or to connect with family and friends was also hindered by the pandemic, making self-care options minimal (Table 2, theme 4, quote a).

Heightened Isolation (Already a Challenge for Community Clinicians)

Clinicians discussed how they felt increasingly isolated without interaction with their colleagues. They felt that the altered care environment was new to them and, on top of that, did not have collegial interactions to navigate and troubleshoot some of their common experiences. They felt professionally isolated (Table 2 theme 4, quote b).

Discussion

This thematic analysis of interviews with community neurologists illustrates the complexities of caring for patients with neurodegenerative disease under pandemic conditions. The 4 main themes that emerged were (1) challenges of the current political climate, (2) lack of support for new models of care, (3) the experience of serving on the frontline of suffering, and (4) looking out for themselves. This study explored the effects of COVID-19 on neurologists practicing in non-academic community settings.

Participants described a lack of support for new models of care as a primary barrier to their professional work. As public health guidelines were rapidly changing, neurology providers expressed feelings of confusion surrounding new regulations and frustration with a lack of institutional support for telemedicine. Surveys of US neurologists early in the pandemic corroborate that outpatient neurologists experienced problems with telemedicine implementation, inconsistent safety protocols, and lack of clarity around changes in insurance coverage.15 This finding complements existing prepandemic literature showing neurologists’ clinical and clerical workload as a primary contributor to reduced career satisfaction.16

Participants in this study also described how the American political environment compromised patient trust in medical providers. In fact, this finding among American neurologists contrasts with a study done in China in which health care providers cited a sense of national unity as a source of resilience.7 In the United States, prior studies showed declining public trust in physicians overtime.17,18 However, the pandemic had accelerated the rapid dissemination of unregulated clinical information to the public, facilitating the spread of misinformation.9 This then has further divided the public's trust in clinicians and further strained relationships.

Neurology providers in this study also reported a number of aspects of the pandemic that affected them on a personal level. They described increased challenges around self-care, including an increased sense of isolation. Compared to neurologists working in academic environments, there also appeared to be a lack of institutional support or awareness of self-care needs.19 COVID-19 contributed to heightened feelings of helplessness as they bore witness to how the pandemic contributed to the already substantial suffering of patients with neurodegenerative disease. Patients with neurodegenerative disease also have a number of characteristics—older age, higher likelihood of living in an institutional setting, and higher prevalence of impaired mobility and cognition—that increase their risk of contracting and suffering complications from COVID-19.8 A feeling of disempowerment has previously been described as an important contributor to burnout among American neurologists.16

Our study adds to the emerging body of literature examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care providers. Studies in the past have illuminated how providers have struggled during the pandemic as they adjust to changes in the acceptable standard of care, exhaustion, moral distress of allocation decisions, barriers to care delivery and communication, and decision-making under uncertainty.1 Studies have also started to uncover social support and transcendence as important sources of resilience.7 However, all qualitative studies to date have focused on physicians directly involved in the care of patients with COVID-19 and primarily in academic settings. Given the duration of the pandemic, this study provides important evidence regarding the secondary effects of the pandemic on physicians caring for patients with chronic illness in the community.

Our study also contributes evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic to the growing body of literature on the epidemic of neurologist burnout. Clinician burnout, defined as the syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and sense of low personal accomplishment,20 had already reached crisis levels in neurologists before the pandemic.21,22 Clinician burnout is associated with decreased patient satisfaction and worse clinical outcomes.23–25 Neurology practice is associated with especially high rates of burnout and low satisfaction with work-life balance compared to other medical fields.26 Qualitative studies have defined important contributors to neurologist burnout, including excessive workload, bureaucratic policies and systemic factors contributing to feelings of disempowerment, and limitations on professional autonomy.16 Burnout is common across all clinical settings and neurology subspecialties. However, working in a community practice is a risk factor for lower career satisfaction and reduced quality of life.11 Given the association between burnout and professional work effort,27,28 the contribution of the COVID-19 pandemic to neurologist burnout is likely exacerbating an already strained workforce in which shortages of neurology-trained specialists already affect most areas of the United States and are expected to worsen in the coming years.29

Our findings call for better structural strategies to support the neurology workforce during the pandemic and beyond at the individual, organizational, and societal levels.30 At the societal level, broad resources and funding are needed to enhance mental health programs and to provide opportunities to mitigate the culture of silence around discussing and addressing clinician well-being.31 Clinicians are expected to work long hours in high-stress roles and to bear witness to substantial human suffering without the opportunity to express their mental health challenges due to the culture of silence31 among their superiors and colleagues. It is imperative to create a supportive culture in medicine that accepts and addresses burnout and other mental health challenges during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. At the organizational level, efforts should address clinician isolation by building infrastructure to enable physicians to engage with peers and to process moral injury to reduce burnout and associated negative impacts on patient care.32 Work systems can be adequately resourced and redesigned with a human-centered approach to enable clinicians to focus on the meaning of their work. Frustration regarding telemedicine implementation can be mitigated through avenues such as SCAN-ECHO, an interactive teleconferencing program that connects medical providers with live training from specialists.33 In addition, community-based practices could identify individuals within their practice who can provide similar training and technical support for patients and clinicians in the virtual care environment. This could be done by sharing prerecorded video guides to telemedicine with patients, their caregivers, and clinicians. At the individual level, neurology workforce burnout should be addressed by identifying and providing resources that are tailored to meet their needs.34 This could be accomplished through sharing of existing resources for personal care, including resiliency training, mental health care, meditation and mindfulness, and other simple yet effective resources to move the needle on self-care.35 However, these approaches alone are not sufficient unless accompanied by institutional and cultural change that is sustained and responsive to feedback over time. Incorporating this multipronged approach could curtail burnout, improve neurologist well-being, and connect clinicians with resources that affect patient care.

There are several limitations to our study. It may not represent the experience of clinicians living outside of the United States, particularly because the American political environment was identified by providers as a source of stress. It also may not capture the experience of providers in all of Colorado or regions of the United States outside of our study area. The rapidly changing nature of the pandemic and institutional guidelines may cause these experiences to evolve over time. All interviews were conducted over the phone, which may have limited the building of rapport with recipients to elicit more sensitive themes. Strengths of our study include its inclusion of providers working in the community, focus on providers working with high-risk patients in the ambulatory setting, and the timeliness of the questions during spikes in cases of infection. In addition, this study was conducted by a multidisciplinary team of clinicians, health services researchers, and qualitative methodologists.

This study provides evidence about the experience of clinicians caring for patients with neurodegenerative conditions in the community-based, outpatient setting. Neurology providers are finding it difficult to maintain a therapeutic relationship with patients during a period of politicized medicine and misinformation and feel there is a lack of support for new models of care. Our study suggests that strategies to promote engagement and to decrease systematic contributors to burnout are essential to maintaining quality of care and supporting the neurology workforce during and after the pandemic.36,37 This has implications for how best to support neurology providers during the remainder of this pandemic and when the next public health emergency emerges.

Acknowledgment

This work would not have been possible without the funders and the participation of clinicians. The authors thank Laura Palmer, Raisa Syed, and Christine Martin for their assistance as part of the larger study team.

Glossary

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

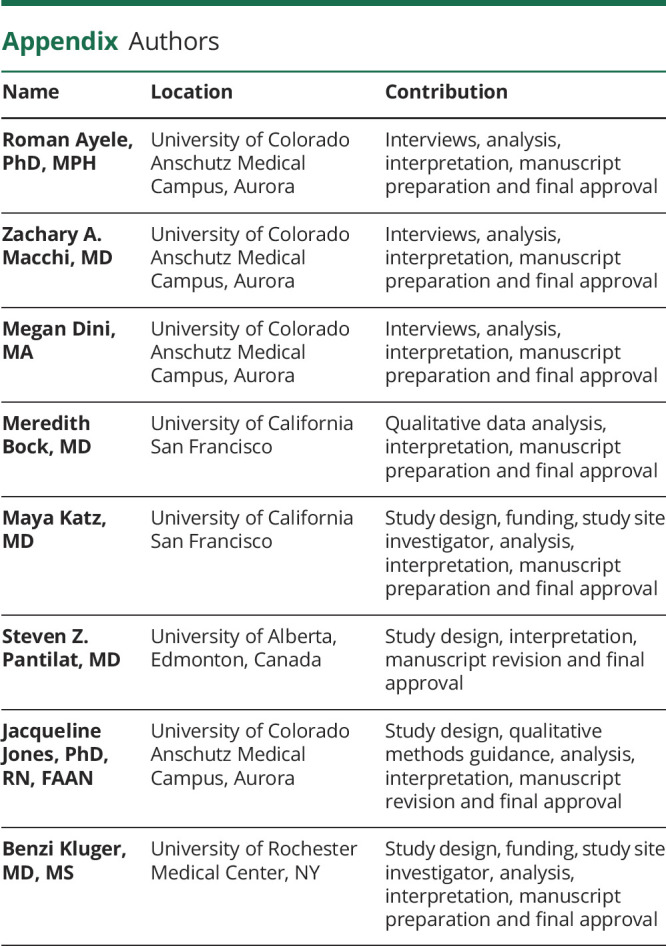

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

COVID-19 Resources: NPub.org/COVID19

Study Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the NIH under award R01NR016037 and the National Institute on Aging Multidisciplinary Research Training in Palliative Care and Aging (T32AG044296). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure

Dr. Ayele, Dr. Macchi, Ms. Dini, Dr. Mock, Dr. Katz, Dr. Pantilat, Dr. Jones, and Dr. Kluger report no disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Butler CR, Wong SPY, Wightman AG, O'Hare AM. US clinicians' experiences and perspectives on resource limitation and patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2027315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Guidance for Establishing Crisis Standards of Care for Use in Disaster Situations, Institute of Medicine. Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response. National Academies Press; 2012. Accessed February 5, 2021. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201063/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Pandemic influenza preparedness framework for sharing of influenza viruses and access to vaccines and other benefits. Accessed February 5, 2021. apps.who.int/gb/pip/pdf_files/pandemic-influenza-preparedness-en.pdf.

- 4.Shellhaas RA. Neurologists and COVID-19: a note on courage in a time of uncertainty. Neurology. 2020;94(20):855-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bersano A, Pantoni L. On being a neurologist in Italy at the time of the COVID-19 outbreak. Neurology. 2020;94(21):905-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahmud N, Goldberg DS, Kaplan DE, Serper M. Major shifts in outpatient cirrhosis care delivery attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cohort study. Hepatol Commun. 10.1002/hep4.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. . The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(6):e790-e798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau KHV, Anand P. Shortcomings of rapid clinical information dissemination: lessons from a pandemic. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11(3):e337-e343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saag MS. Misguided use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19: the infusion of politics into science. JAMA. 2020;324(21):2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busis NA, Shanafelt TD, Keran CM, et al. . Burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being among US neurologists in 2016. Neurology. 2017;88(8):797-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855-866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(9):1212-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ, Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma A, Maxwell CR, Farmer J, Greene-Chandos D, LaFaver K, Benameur K. Initial experiences of US neurologists in practice during the COVID-19 pandemic via survey. Neurology. 2020;95(5):215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyasaki JM, Rheaume C, Gulya L, et al. . Qualitative study of burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being among US neurologists in 2016. Neurology. 2017;89(16):1730-1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Hero JO. Public trust in physicians: U.S. medicine in international perspective. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1570-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mechanic D, Schlesinger M. The impact of managed care on patients' trust in medical care and their physicians. JAMA. 1996;275(21):1693-1697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avitzur O. This COVID-19 practice: academic neurology and hospital-based practices hit by pay cuts, furloughs, and loss of job benefits. Neurol Today. Accessed February 24, 2021, journals.lww.com/neurotodayonline/blog/breakingnews/pages/post.aspx?PostID=974. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. Accessed February 5, 2021. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4911781/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Sigsbee B, Bernat JL. Physician burnout: a neurologic crisis. Neurology. 2014;83(24):2302-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Busis NA. To revitalize neurology we need to address physician burnout. Neurology. 2014;83(24):2202-2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. . Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors' perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(7):1017-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1714-1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. . Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. . Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sibbald B, Bojke C, Gravelle H. National survey of job satisfaction and retirement intentions among general practitioners in England. BMJ. 2003;326(7379):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeman WD, Vatz KA, Griggs RC, Pedley T. The Workforce Task Force report: clinical implications for neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):479-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz R, Sinskey JL, Anand U, Margolis RD. Addressing postpandemic clinician mental health. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):981-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro J, McDonald TB, Supporting clinicians during COVID-19 and beyond: learning from past failures and envisioning new strategies. New Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):e142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung S, Dillon EC, Meehan AE, Nordgren R, Frosch DL. The relationship between primary care physician burnout and patient-reported care experiences: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(8):2357-2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arora S, Kalishman S, Thornton K, et al. . Expanding access to HCV treatment: Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project: disruptive innovation in specialty care. Hepatology. 2010;52(3):1124-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel UK, Zhang MH, Patel K, et al. . Recommended strategies for physician burnout, a well-recognized escalating global crisis among neurologists. J Clin Neurol. 2020;16(2):191-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. . Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erickson SM, Rockwern B, Koltov M, McLean RM. Putting patients first by reducing administrative tasks in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):659-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data are available and will be shared on reasonable request from any qualified investigator.