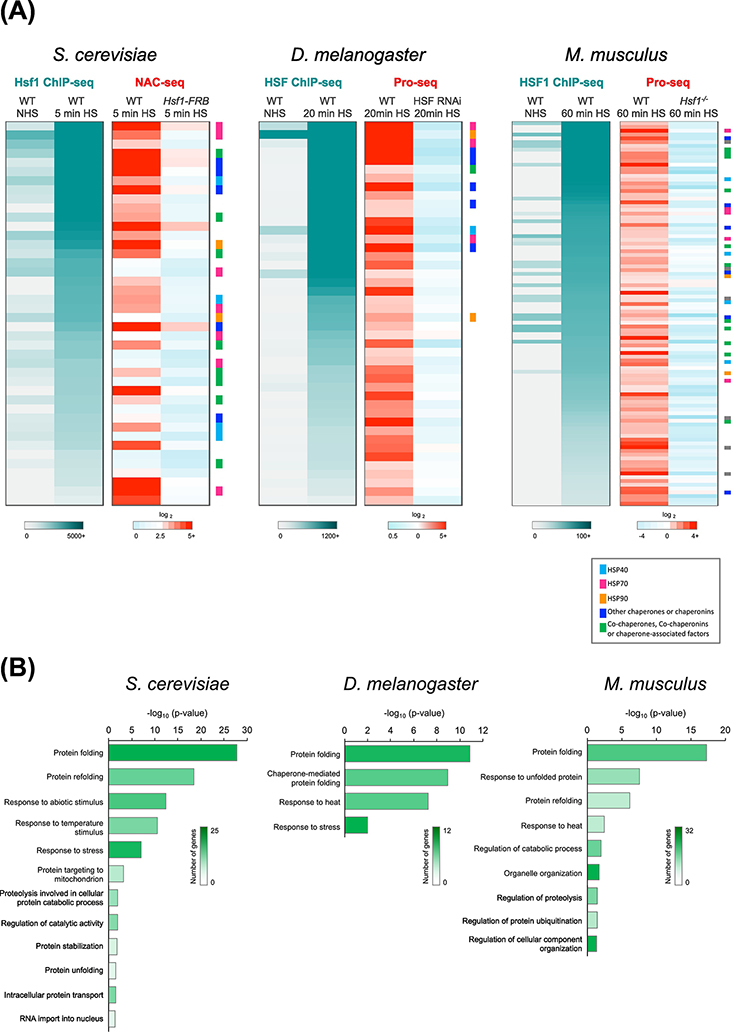

Figure 1. Conservation of the Heat Shock Response in Eukaryotes.

A) Heat Shock Factor 1 (HSF1) binding as determined by ChIP-seq (left, gray to teal) and fold-change in nascent RNA levels as determined by NAC-seq or Pro-seq (right, blue to red) at genes bound and induced by HSF1 in S. cerevisiae (n=42), D. melanogaster S2 cells (n=44) and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs; n=102). HSF1 occupancy was determined under both non-heat shock (NHS) and heat shock (HS) conditions. Fold-change in NAC-seq or Pro-seq reads (HS / NHS) was determined for WT and HSF1-depleted cells. Genes are sorted in descending order of HSF1 ChIP-seq counts (HS condition). Genes encoding molecular chaperones are color coded as indicated by the key. Data were obtained from YeastMine [73], FlyMine [74], Mouse Genome Informatics (http://www.informatics.jax.org) and UniProt [75]. Yeast NAC-seq and Hsf1 ChIP-seq data were obtained from a previous study [37]; Drosophila HSF ChIP-seq and Pro-seq data were provided by F.M. Duarte and M.J. Guertin [42, 44] and MEF HSF1 ChIP-seq and Pro-seq data were provided by D.B. Mahat [43].

B) Gene Ontology (GO) comparison of HSF1-dependent genes in yeast, fly and mouse, respectively, using the Protein Analysis Through Evolutionary Relationships (PANTHER) classification system [76, 77]. Heatmap indicates the number of genes in each GO category. The length of each bar corresponds to the P-value corrected for multiple comparison testing using the Bonferroni method. Test was for enrichment of genes from panel A mapping to the given GO category in comparison to expected distribution of genes in the same category in the reference genome.