Abstract

To compensate for a sessile nature, plants have developed sophisticated mechanisms to sense varying environmental conditions. Phytochromes (phys) are light and temperature sensors that regulate downstream genes to render plants responsive to environmental stimuli1-4. Here, we show that phyB directly triggers the formation of a repressive chromatin loop by physically interacting with VIN3-LIKE1/VERNALIZATION 5 (VIL1/VRN5), a component of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2)5, 6, in a light-dependent manner. phyB and VIL1 cooperatively contribute to the repression of growth-promoting genes through the enrichment of Histone H3 Lys 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3), a repressive histone modification. In addition, phyB and VIL1 mediate the formation of a chromatin loop to facilitate the repression of ATHB2. Our findings show that phyB directly utilizes chromatin remodeling to regulate the expression of target genes in a light-dependent manner.

In the early post-germination stage, dark to light transition reprograms growth strategy of plants to photomorphogenic growth which is defined by open, wide, and green cotyledons and short hypocotyls7, 8. As red/far-red light sensors, phytochromes promote vital developmental processes in plants2-4. Transcriptional regulation by phys is primarily mediated by inhibiting Phytochrome Interacting Factors (PIFs) which belong to the basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) transcription factor family9, 10. Light activated phys inhibit PIFs post-translationally, both by promoting their degradation and by repressing their DNA-binding ability through direct protein-protein interactions10, 11. In the absence of light, PIFs redundantly elongate hypocotyls by positively regulating expression of growth-promoting genes. However, it has been reported that phyB also directly controls the expression of temperature responsive growth-promoting genes2, implying that phyB may also be associated with other transcriptional regulators at target loci.

VIL1 is one of the VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE3 (VIN3) family proteins which contain a PHD finger motif12, 13, and is necessary for the vernalization-mediated repression of flowering repressors, FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) gene family through Polycomb group proteins (PcG)13. The association of PHD finger-containing proteins with PRC2 is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of gene repression by PcG5. The VIN3 family proteins, including VIL1, also can be biochemically co-purified with PRC25, 6. PRC2 directly regulates a number of genes that are involved in various developmental processes in eukaryotes14, 15. PRC2 mediates trimethylation of H3K27 through its histone methyltransferase activity16 and the VIN3 family proteins are necessary to enhance the histone methyltransferase activity in vivo13. The H3K27me3 marks are associated with the down-regulation of nearby genes and heterochromatin formation17. In addition, PcG-mediated gene repression includes the formation of repressive chromatin loop at some target loci both in animals and plants that may provide a structural foundation for repressive chromatin18-21, although the molecular basis of the formation of PcG-mediated chromatin loop remains to be determined.

Interestingly, we observed that seedlings of the vil1 phyB double mutant (vil1-1 phyB-9) have significantly elongated hypocotyls compared to the phyB-9 single mutant under short day (SD) conditions, regardless of growth temperatures (Fig. 1a, b). The vil1 single mutant (vil1-1) also displayed slightly but significantly longer hypocotyls than Col-0 (wild type, WT) under all temperature conditions, indicating that VIL1 and phyB additively inhibit hypocotyl elongation. We observed similar additive effects by VIL1 and phyB in the seedlings grown under long day (LD), continuous white light (WLc) and continuous red light (Rc) conditions, but not in the seedlings grown under continuous dark (Dc) and far-red light (FRc) conditions (Extended Data Fig. 1), indicating red light-dependent contribution by VIL1 to the phyB signaling. PIF4 is a major determinant of hypocotyl elongation under SD conditions22, 23. Therefore, we first examined the genetic relationship between PIF4 and VIL1 by creating the vil1-1 pif4-2 double mutant. The pif4 mutant (pif4-2) is epistatic to vil1 mutant under all tested conditions, indicating that VIL1 functions upstream of PIF4 (Extended Data Fig. 2a, b). pif4-2 is also epistatic to vil1-1 phyB-9 as observed in the vil1-1 phyB-9 pif4-2 triple mutant, further confirming that PIF4 is necessary for hypocotyl elongation observed in vil1 and phyB mutants. Although VIL1 is known to control transcription as a PcG protein, VIL1 does not affect the level of PIF4 mRNA in all tested conditions (Extended Data Fig.2c, d). At both ZT0 (at the end of the night) and ZT6 (middle of the day), PIF4 expression patterns show no significant difference between vil1-1 and WT, and vil1-1 does not affect the level of PIF4 mRNA in the phyB mutant background (Extended Data Fig.2c, d). We also compared endogenous PIF4 protein levels between Col-0 and vil1-1. At ZT6, when PIF4 protein is most abundant24 in SD, the PIF4 protein level is unchanged by vil1 (Extended Data Fig. 2e), indicating that VIL1 does not regulate the growth response through the level of PIF4 protein.

Fig. 1 ∣. VIL1 and phyB synergistically inhibit hypocotyl elongation by regulating growth-promoting genes.

a, Hypocotyl length phenotype of seedlings of each genotypes grown for 7 days at four different temperatures (12°C, 17°C, 22°C, and 27°C) in SD condition (8h light/16h dark; 8L/16D). b, Box plot for quantification of hypocotyl length. n = 25 seedlings. The box plot boundaries reflect the interquartile range, the horizontal line is the median and the whiskers represent 1.5X the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles. The letters marked as same color above each box indicate statistical difference between the genotypes at each temperature determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05). c - e, ATHB2 (c), HFR1 (d) and PIL1 (e) mRNA expression levels in Col-0, vil1-1, phyB-9 and vil1-1phyB-9 seedlings grown for 7 days at four different temperatures in SD. Samples were collected at ZT0. The expression levels were normalized to that of PP2A, and further normalized by the transcript level of Col-0 at ZT0, at 12°C. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates). The letters marked as same color above each bar indicate statistical difference between the genotypes at each temperature determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05).

PIF4 is a main transcriptional activator of several growth-promoting genes and the active form of phyB inhibits the expression of the same growth-promoting genes both by transcriptional and post-translational regulations2. Interestingly, a growth-promoting PIF4 target gene, ATHB2, which is up-regulated in phyB-9 mutants and a direct target of phyB2, is also slightly up-regulated in vil1-1 mutants. We were able to detect a similar increase of ATHB2 expression in vil1 at all tested conditions (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, its expression was further increased in vil1-1 phyB-9 compared to either of the single mutants, suggesting a synergistic transcriptional repression by phyB and VIL1, regardless of growth temperatures (Fig. 1c). Differences observed in the levels of ATHB2 expression correlate with the degree of hypocotyl elongation (Fig. 1b, c). The ATHB2 expression peaked at ZT0 (Fig. 1c) when PIF4 activity is at the highest and then rapidly declined during the daytime22 (Extended Data Fig. 3a). In addition, we found that other phyB target genes, HFR1 and PIL1, also displayed expression patterns similar to ATHB2 in the vil1-1 and vil1-1 phyB-9 mutants (Fig. 1d, e, Extended Data Fig. 3b, c). These genes have been reported as marker genes for hypocotyl elongation, and PIF4 promotes their expressions25, 26 (Extended Data Fig. 4). Therefore, VIL1 and phyB synergistically repress this group of phyB target genes during the daytime. In contrast, the expression of growth-promoting, hormone-signaling genes such as YUC8 and IAA29, which have been reported as night-time responsive genes, showed dependence on phyB2, 27, but not on VIL1 (Extended Data Fig. 5), even though they are also direct target loci of PIF4 and PIF4 promotes their expression2. Taken together, our results indicate that VIL1 and phyB synergistically inhibit the growth response by regulating a subset of the growth-promoting genes, independent of PIF4.

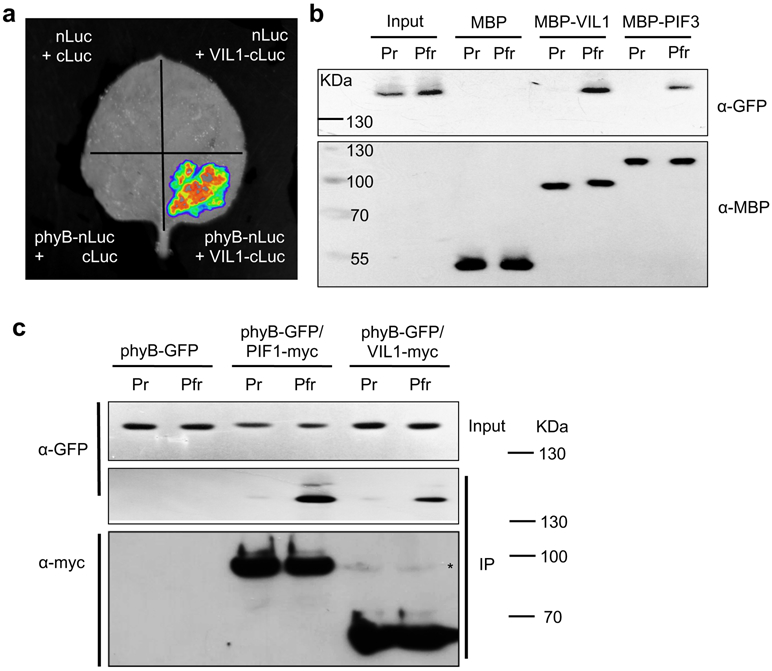

Our genetic analyses suggest that VIL1 acts together with phyB to repress a subset of PIF4 target genes (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig.3). Therefore, we tested whether phyB employs VIL1-PRC2 to trigger chromatin remodeling at the target gene loci. To determine direct physical interaction between VIL1 and phyB, we first employed the split luciferase complementation assay by transiently expressing both proteins into Nicotiana benthamiana. Each split luciferase protein was conjugated with phyB (phyB-nLuc) and VIL1 (VIL1-cLuc), which generated strong luciferase activity compared to the negative controls (Fig. 2a). To determine if this interaction resulted from direct protein-protein interaction between phyB and VIL1, we performed in vitro pull-down assays. Purified MBP-VIL1 protein was able to bind purified and reconstituted phyB-GFP protein (Fig. 2b). We further confirmed their interactions in the seedlings of Arabidopsis expressing both phyB-GFP and VIL1-myc by using in vivo co-immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, VIL1 proteins preferentially interact with the active Pfr form of phyB, both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 2b, c). Since phyB inhibits PIF4 through direct protein-protein interaction, we also evaluated whether VIL1 protein directly interacts with PIF4 protein. However, we did not observe significant interaction between VIL1 and PIF4 proteins (Extended data Fig. 6). Therefore, our results support that light-activated phyB directly interacts with VIL1 to regulate the expression of growth-promoting genes.

Fig. 2 ∣. VIL1 preferentially interacts with the active form of phyB both in vivo and in vitro.

a, Split luciferase complementation assay between VIL1 and phyB proteins in N. benthamiana. The experiment was repeated at least two times independently with similar results. b, In vitro pull-down assay showing the direct interaction between MBP-VIL1 and phyB-GFP proteins. phyB-GFP was expressed in yeast cells while MBP, MBP-VIL1 and MBP-PIF3 proteins were expressed in E. coli. phyB-GFP protein was pre-treated with red light (10.7 μmol m−2 s−1 for 4 mins to make Pfr, an active form of phyB) or far-red light (2.4 μmol m−2 s−1 for 18 mins to make Pr, an inactive form of phyB), respectively. Proteins were pull-downed by amylose-resin bound MBP and detected by anti-GFP and anti-MBP antibodies. The experiment was repeated at least two times independently with similar results. c, Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay demonstrating an in vivo interaction between VIL1 and phyB. Transgenic plants expressing p35S:phyB-GFP alone or with pVIL1:VIL1-myc or with p35S:PIF1-TAP were used. Dark grown seedlings were treated red-light (Pfr) or kept in the dark (Pr) before doing IP. VIL1-myc and PIF1-myc proteins were immunoprecipitated by anti-myc antibody and co-immunoprecipitated phyB-GFP protein was detected by anti-GFP antibody. The asterisk indicates the VIL1-myc protein bands. The experiment was repeated at least two times independently with similar results.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis of phyB revealed that about 95 genes, including ATHB2, HFR1 and PIL1, are direct targets of phyB2. To examine whether VIL1 is enriched at the growth-promoting genes where phyB is also known to be located, such as ATHB2, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR). The ATHB2 locus includes several G-box (CACGTG) sequences upstream of the gene body, and phyB and PIF4 binding peaks at around the same G-box region located in the 6kb upstream from the transcription start site (TSS)2, 28, which is designated as RE1 (Fig. 3a). Weaker peaks of phyB and PIF4 binding at other G-box regions, including RE2, are also observed at the ATHB2 locus compared to RE1 (Fig. 3a). We performed ChIP-qPCR using the VIL1 complementation transgenic lines (pVIL1:VIL1-myc/vil1-1) (Extended Data Fig. 7a to d) and confirmed that VIL1 is highly enriched at the RE1 and P2 (TSS) regions (Fig. 3b). Moreover, VIL1 is also enriched at RE2 and the middle region of the gene body. We further tested VIL1 enrichment at the HFR1, and PIL1 loci and confirmed that VIL1 is enriched at these loci as well (Extended Data Fig. 7e, f). In addition, we observed that VIL1 protein levels are diurnally regulated, displaying the highest level in the middle of day (around at ZT6), suggesting that light increases VIL1 expression (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Similarly, we also observed that VIL1 mRNA expression increases slightly during the day (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Immunoblot analysis showed that dark-incubated VIL1 protein is stabilized by light exposure and gradually accumulated depending on the incubation time under light (Extended Data Fig. 8c), indicating that light indeed stabilizes VIL1 protein. Consistently, we observed that VIL1 enrichment at the ATHB2 locus were higher at ZT6 than at ZT0 (Fig. 3b). However, VIL1 enrichment at FLC locus was not increased at ZT6 (Extended Data Fig. 8e, f), implying the VIL1 enrichment at ATHB2 locus is not simply due to the increased level of VIL1 protein. Given the direct interaction between phyB and VIL1 (Fig. 2), we addressed whether phyB affects the VIL1 enrichment at ATHB2 locus. Although phyB does not affect the stability of VIL1 protein (Extended Data Fig. 8d), the VIL1 enrichment at ATHB2 is significantly reduced at both RE1 and P2 (TSS) regions in the phyB-9 background (Extended Data Fig. 8g). Furthermore, the VIL1 enrichments at HFR1 and at PIL1 are also significantly reduced in the phyB-9 background (Extended Data Fig. 7f), indicating that phyB enhances VIL1 binding to the growth promoting genes during the day.

Fig. 3 ∣. VIL1 and phyB cooperate to remodel the chromatin of ATHB2 locus to control its expression.

a, ATHB2 locus, G-box elements, ChIP-qPCR amplicons. The red vertical bars indicate G-box regions. RE1, RE2, P1, P2, P3, and P4 indicate ChIP-qPCR amplicons. b, VIL1 targeting profile on the ATHB2 locus at both ZT0 and ZT6. The ChIP assay used anti-myc antibody on seven days old seedlings grown at 22°C in SD. The ChIP assay in Col-0 was used as a negative control. The immunoprecipitated DNA relative to input was further normalized to that of 5S rDNA. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 3, biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistical differences in a two tailed student t-test (***, P < 0.0005). c and d, H3K27me3 levels in Col-0, vil1-1, phyB-9, vil1-1phyB-9, and pif4-2 at both ZT0 (c) and ZT6 (d). This ChIP assay used anti-H3K27me3 antibody and anti-H3 antibody. The y axis indicates H3K27me3 enrichment relative to H3 enrichment. The values were further normalized to the enrichments of Col-0 at RE1, at ZT0. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates). The asterisks indicate statistical differences in a two-tailed student t-test (P < 0.05).

Given that VIL1 is a component of the PRC2 which mediates H3K27 trimethylation, we performed H3K27me3 ChIP-qPCR in the mutants both at ZT0 and ZT6 (Fig. 3c, d) and found that, regardless of the time points, H3K27me3 was enriched at around the RE regions where the phyB enrichments were observed at the ATHB2 locus2. The distribution of H3K27me3 enrichment on the ATHB2 locus is also consistent with our previous H3K27me3 ChIP-seq results29 (Extended Data Fig. 9) and with previous ChIP-seq results of CURLY LEAF (CLF) and SWINGER (SWN) which are two major catalytic subunits of PRC230 (Extended Data Fig. 9). H3K27me3, CLF-GFP and SWN-GFP were enriched in the HFR1, and PIL1 loci as well (Extended Data Fig. 9). Interestingly, the H3K27me3 enrichments on ATHB2 were dependent on both VIL1 and phyB. Furthermore, the H3K27me3 levels are further reduced in vil1-1 phyB-9, indicating that both VIL1 and phyB cooperatively mediate the H3K27me3 deposition at the ATHB2 locus (Fig. 3c, d). However, the level of H3K27me3 enrichment is not at all affected in pif4 mutant, indicating that the enrichment of H3K27me3 at the ATHB2 locus is independent of PIF4 (Fig. 3c, d), despite that transcription of ATHB2 is compromised in pif4 mutant (Extended Data Fig. 4a). This indicates that PIF4 does not play a role in the H3K27me3 enrichment at ATHB2 locus. Although the transcription of ATHB2 shows diurnal patterns of expression, we did not observe diurnal variations in the level of H3K27me3 at the ATHB2 locus (Fig. 3c, d), suggesting that the level of H3K27me3 enrichment is rather stably maintained to create a repressive chromatin environment. Similarly, we also observed that the H3K27me3 enrichment at HFR1 and PIL1 loci depends on both VIL1 and phyB (Extended Data Fig. 7g). Taken together, our results indicate that VIL1 and phyB are necessary for the H3K27me3 deposition at the target loci by PRC2 in a PIF4-independent manner.

It is interesting to note that the phyB binding sites are located quite far from the TSS of ATHB22. Previous studies have shown that some PRC2 target loci undergo PcG-dependent formation of short-distance repressive chromatin loop18-20. Intriguingly, we detected abundant formations of the chromatin loop between RE1 and P2 (TSS) of the ATHB2 locus (Fig. 4c - f). In addition, the loop depends on the presence of both phyB and VIL1 (Fig. 4c - f), indicating cooperative roles of phyB and VIL1 in mediating the formation of the chromatin loop (Fig. 4c - f). We observed >2-fold increase in the formation of the loop at ZT6 compared to ZT0 (Fig. 4b). At ZT6, the level of ATHB2 mRNA is repressed which correlates with the highest level of VIL1 protein and more abundant active Pfr form of phyB (Extended Data Fig. 3a, Extended Data Fig. 8a), implying that the formation of the chromatin loop may be light-dependent through the phyB-VIL1 interaction. Therefore, we examined the formation of the chromatin loop at ATHB2 locus upon light exposure (Fig. 4g, h). We were able to observe the chromatin loop at ATHB2 locus within 4 hours of exposure to red-light (10.7 μmol m−2 s−1). In addition, this red-light induced chromatin loop was rapidly reduced by far-red light (2.4 μmol m−2 s−1) treatment within 1 hour, indicating the dynamic light-responsive nature of the chromatin loop formation (Fig. 4g, h). An Arabidopsis homolog of Su(z)12, VERNALIZATION 2 (VRN2), is a core component of PRC2 which copurifies with VIL15. Interestingly, vrn2 mutants behave similarly to vil1 mutants and also abolish the chromatin loop at ATHB2 (Extended Data Fig. 10d, e), further supporting that the PRC2 is required for the formation of chromatin loop. However, PIF4 is again dispensable for the formation of chromatin loop (Fig. 4c - f). Therefore, our results revealed that phyB and VIL1 provide an additional layer of regulation through the formation of chromatin loop, which is independent of the phyB-PIF4 regulatory module (Extended Data Fig. 10f, g).

Fig. 4 ∣. phyB and VIL1 cooperatively form a repressive chromatin loop to inhibit ATHB2 expression.

a, ATHB2 locus, G-box elements, ChIP-qPCR amplicons, DpnII enzyme sites and 3C-qPCR amplicons. The green and red vertical bars indicate DpnII enzyme and G-box regions respectively. RE1, RE2, P1, P2, P3, and P4 indicate ChIP-qPCR amplicons. F0 to F6, R0 to R6 and Anchor indicate 3C-qPCR amplicons. b, Fold changes between the values in peaks at ZT0 and at ZT6 in 3C assay shown in panel c to f. F sets and R sets indicate Forward primer sets and Reverse primer sets respectively. c - f, Relative interaction frequency (RIF) in 3C assay between the Anchor primer and a series of F(forward) primers (c and e), or between the Anchor primer and a series of R(reverse) primers (d and f) in Col-0, vil1-1, phyB-9, vil1-1phyB-9, and pif4-2 at both ZT0 (c and d) and ZT6 (e and f). g and h, Relative interaction frequency (RIF) in 3C assay between the Anchor primer and a series of F (forward) primers (g), or between the Anchor primer and a series of R (reverse) primers (h). Col-0 seedlings were grown in the dark for 4 days and then transferred to red light (10.7 μmol m−2 s−1) for 4 hours or kept in the dark for 4 hours. To check far-red light can reverse the loop formation, we further treated far-red light (2.4 μmol m−2 s−1) for 1 hour after red light treatment. The enrichment of each regions was normalized to that of PP2A. These values were further normalized to the enrichment of each regions in pATHB2:ATHB2-Flag plasmid DNA. In c – h, Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates).

Chromatin remodeling by the phyB-VIL1 module ensures the repression of growth genes which are often activated by PIF4. The growth-promoting genes regulated by phyB and PIF4 are also regulated by other PIFs31, 32, as photomorphogenesis is redundantly regulated by multiple PIFs. phyB-9 pif4-2 mutants display longer hypocotyls than pif4-233, because the absence of phyB creates a favorable condition for other PIF proteins to function. Our observation that vil1-1 phyB-9 pif4-2 triple mutant displays a similar hypocotyl length to that of phyB-9 single mutant supports the notion that the phyB-VIL1 regulatory module inhibits the transcriptional activation of growth-promoting genes by other PIFs. (Extended Data Fig. 2a, b). Therefore, chromatin architectures created by the phyB-VIL1 module ensure the optimal repression of growth-promoting genes in the presence of light.

Our study shows that light stabilizes VIL1 protein and light-activated phyB directly interacts with each other to mediate chromatin remodeling through both the deposition of H3K27me3 and the formation of chromatin loop. Therefore, VIL1 and phyB cooperatively mediate the light-dependent synergistic repression of growth-promoting genes. PRC2-mediated gene repression by the H3K27me3 deposition is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism to control developmentally regulated genes in higher eukaryotes34-38. Our study demonstrates that light signaling also employs PRC2-mediated gene-repression system to fine-tune gene expression during photomorphogenesis. The direct link between an environmental sensor (phyB) and chromatin-modifying complex (VIL1-PRC2) shows an example in which a sensor directly modulates chromatin remodeling.

Since the discovery of topologically associating domains (TADs) and chromatin loops, particular attention has been paid to how these three-dimensional (3D) genomic structures change during development and cellular differentiation when cells need to precisely and dynamically tune gene expression programs39, 40. In the Arabidopsis genome, chromatin loops within short distance are more abundant than long-range loops, especially within H3K27me3-enriched loci41. In this study, we show that an environmental sensor, phyB, mediates the formation of a chromatin loop in a cooperative manner with PRC2. The red light-dependent nature of the formation of chromatin loop demonstrates that dynamic changes in 3D chromatin structure play roles in fine-tuning developmentally regulated genes upon environmental stimuli. Direct elicitation of chromatin remodeling by environmental sensors, such as phys, may enable plants to rapidly respond to dynamically changing environments. Indeed, we observed that the formation of the chromatin loop occurs rather rapidly upon red-light exposure, creating a repressive chromatin architecture which compensates for another regulatory module (i.e., phyB-PIF4 regulatory module; Extended Data Fig. 10f, g). These multiple layers of regulatory modules employed by phyB ensure optimal regulation of growth-promoting genes.

Although we show that the enrichment of VIL1 at the ATHB2 loci is enhanced by phyB (Extended Data Fig. 8g), neither VIL1 nor phyB is a DNA binding protein and the phyB-VIL1 module is PIF4-independent. A class of DNA-binding proteins, VIVIPAROUS1/ABI3-LIKE1 (VAL1) and VAL2, bind to the RY motif42, and are required for the enrichment of PRC2 at target loci43. Interestingly, G-box elements where phyB and PIFs bind are often coupled with other elements targeted by their corresponding transcription factors44. Indeed, the RY motif is one of the G-box-coupled elements in the PIFs binding sites44. It remains to be determined whether VAL1/VAL2 transcription factors also play roles in light-dependent PRC2 activity.

Our study shows an example in which molecular communication between the sensors and chromatin association factors occurs in plants, aiding the robust response to environmental variations. Given that the diverse roles of phys as light and temperature sensors, our findings are also particularly important in understanding how plants respond to climate change.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

All Arabidopsis thaliana plants used in this study were in Col-0 background and grown at continuous 12, 17, 22, or 27°C in a growth room with 8-h-light/16-h-dark short day (SD) cycle. For assays, seven days old seedlings were used after inducing the germination at 22°C for 24 hours. The mutants of vil1-1 (SALK_136506), vil1-2 (SALK_140132), pif4-2 (Sail_1288_E07), vrn2 (SALK_201153) and phyB-9 were used in this study. Higher order mutants were generated by genetic crossing. To generate pVIL1:VIL1-myc/vil1-1 and pVIL1:VIL1-Flag/vil1-1 transgenic line, the VIL1 genomic DNA was cloned into the pENTR_dTOPO vector and transferred to pGWB16 or pEarleyGate 302 vector by gateway cloning method and transformed to vil1-1 plants by Agrobacterium floral dip method. pVIL1:VIL1-myc/vil1-1phyB-9 line was generated by genetic crossing. The transgenic plants expressing both p35S:phyB-GFP45 and pVIL1:VIL1-myc used for the Co-IP assay were generated by genetic crossing. To generate pATHB2:ATHB2-Flag construct, the ATHB2 genomic DNA was cloned into the modified pPZP211 vector.

RNA and protein analysis

Total RNA was isolated from seven days old seedlings grown at the different temperatures by TRIzol method and incubated with DNase (Promega) for 30min at 37°C to remove residual genomic DNA before reverse transcription. 1 μg of total RNA was used for reverse transcription by M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The transcript levels of target genes were determined by real-time PCR using specific primer sets (Supplementary Table 1) and normalized with that of PP2A. Two biological replicates were performed, with four technical replicates each. For protein analysis, seedlings were frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized. Total protein was extracted with urea-denaturing buffer (100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-Cl, and 8 M urea, pH 8.0, 1mM PMSF, Protease inhibitor cocktails) and the debris was removed by centrifugation. The extracted proteins were further denatured by boiling at 100°C for 5 min with 1X SDS sample buffer. The protein levels were detected by immunoblot analysis using an anti-myc antibody (Santa Cruz, c-myc (9E10) X antibody, sc-40 X, 1:10000 dilution for western blot), anti-PIF4 antibody (Agrisera, AS16 3955, 1:1000 dilution for western blot), anti-tubulin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, anti-α-Tubulin antibody, T5168, 1:10000 dilution for western blot), anti-RPT5 (Enzo Life Sciences, BML-PW8770-0025, 1:10000 dilution for western blot).

Split luciferase assay

PHYB and VIL1 were cloned into pPZP211-nLuc and pPZP211-cLuc vectors, respectively (modified pPZP211 vectors; 35S promoter driven, n-terminal half of luciferase (nLuc) tag or c-terminal half of luciferase (cLuc) tag). Each construct was then infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana leaf epidermal cells. Three days after the infiltration, the luciferase was activated by luciferin solution (0.1% triton X-100, 1mM luciferin) and the signal was detected under the NightOwl II LB 983 in vivo imaging system.

In vitro pull-down assay

MBP, MBP-VIL1, MBP-PIF3 and MBP-SPA1 were expressed in E.coli and purified using amylose-agarose beads, while phyB-GFP46 was expressed in yeast cells. Amylose-agarose bound MBP, MBP-VIL1 and MBP-PIF3 were used to pull-down equal amount of crude extracts of phyB-GFP protein. phyB-GFP protein was pre-treated with red (10.7 μmol m−2 s−1) or far-red (2.4 μmol m−2 s−1) lights to make Pfr or Pr forms, respectively. And amylose-agarose bound MBP, MBP-VIL1 and MBP-SPA1 were used to pull-down GST-PIF4 which was also expressed in E. coli. MBP-SPA1 was used as a positive control as shown previously47. After the pull-down experiment, beads were re-suspended in 50 μL 1X SDS sample buffer. 47 μL of re-suspended protein in 1X SDS sample buffer was used to detect interacting phyB-GFP or GST-PIF4, while remaining 3μL was used to detect MBP, MBP-VIL1 and MBP-PIF3 (or MBP-SPA1) input bait proteins. Pull-down samples were loaded onto a SDS-PAGE gel and detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-GFP antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-9996, 1:10000 dilution for western blot), anti-GST HRP conjugate (GE healthcare, GERPN1236) and anti-MBP antibody (NEB, E8032S, 1:10000 dilution for western blot).

In vivo co-immunoprecipitation assay

Four-day old dark grown seedlings of transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing phyB-GFP and VIL1-myc or phyB-GFP and TAP-PIF145 were first treated with proteasome inhibitor (Bortezomib) for 4 hours under complete darkness and then either kept in the dark or exposed to the red-light (10.7 μmol m−2 s−1). VIL1-myc and TAP-PIF1 were immunoprecipitated using anti-myc antibody. Following immunoprecipitation (IP), beads were re-suspended in 50 μL 1X SDS sample buffer. 47 μL of re-suspended protein in 1X SDS sample buffer was used to detect interacting phyB-GFP, while remaining 3 μL is used to detect immunoprecipitated VIL1-myc or PIF1-myc. Proteins were separated on a 8 % SDS-PAGE gel and detected by immunoblot analysis using anti-GFP antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-9996, 1:10000 dilution for western blot) and anti-myc antibody (Santa Cruz, c-myc (9E10) X antibody, sc-40 X, 1:10000 dilution for western blot).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Seedlings were crosslinked in 1 % formaldehyde under vacuum for 20 min (10 min – break – 10 min) and then quenched by adding glycine (final - 0.125 M) with vacuum for 5min. The seedlings were collected and finely ground in liquid nitrogen. The chromatin complexes were isolated and sonicated with a Bioruptor (30 sec on / 2 min 30 sec off cycles) with high-power output to obtain 200- to 500-bp DNA fragments. Protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated using the antibodies [anti-myc antibody (Santa Cruz, c-myc (9E10) X antibody, sc-40 X), anti-H3K27me3 antibody (Millipore, 07-449), anti-H3 antibody (Abcam, ab1791)]. The cross-linking was then reversed and the enrichment of DNA fragments was determined by real-time PCR using specific primer sets (Supplementary Table 1). Two (for H3K27me3 enrichments) or Three biological replicates (for VIL1 enrichments) were performed, with four technical replicates each.

Chromatin conformation capture (3C) assay

Seedlings were cross-linked in 2 % formaldehyde for 30 minutes (10 min – break – 10 min – break - 10 min) and then quenched by adding glycine (final - 0.125 M) with vacuum for 5min. The seedlings were collected and finely ground in liquid nitrogen. The nuclei were isolated and the chromatin was digested by DpnII restriction enzyme (NEB, R0543M, Size=5,000 units ) at 37°C for overnight. For ligation, T4 DNA ligase (NEB, M0202M, Size=100,000 units) was treated for 5 hours at 16°C and for 2 hours at room temperature. Ligated DNA was purified by phenol/chloroform/isoamyl-alcohol (25:24:1) extraction and ethanol precipitation. Quantitative PCR was performed to calculate the relative interaction frequencies. The specific primer sets used in 3C-qPCR analysis were listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. VIL1 and phyB synergistically inhibit hypocotyl elongation under various light conditions.

a, Hypocotyl length phenotype of seedlings of each genotypes grown for 7 days in long day (LD) (16h light/8h dark; 16L/8D) or for 4 days in continuous white light (WLc) conditions. Scale bar: 5 mm. b - c, Quantification of hypocotyl length of seedlings grown in LD (b) or WLc (c), n = 25 seedlings. d, Hypocotyl length phenotype of seedlings of each genotype grown for 4 days in continuous red (Rc), far-red (FRc) or dark (Dc) conditions. The seedlings were treated with white light for 6 hours to induce germination before incubating under each light conditions. Scale bar: 5 mm. e - g, Quantification of hypocotyl length of seedlings grown in Rc (e), FRc (f), and Dc (g), n = 25 seedlings. In b - c and e - g, The box plot boundaries reflect the interquartile range, the horizontal line is the median and the whiskers represent 1.5X the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles. The letters above each box indicate statistical difference between the genotypes determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05).

Extended Data Fig. 2. VIL1 does not regulate the plant growth through PIF4.

Hypocotyl length of seedlings of each genotypes grown for 7 days at four different temperatures (12°C, 17°C, 22°C, and 27°C) in SD. b, Quantification of hypocotyl length, n = 20 seedlings. The box plot boundaries reflect the interquartile range, the horizontal line is the median and the whiskers represent 1.5X the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles. The letters marked as same color above each box indicate statistical difference between the genotypes at each temperature determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05). c and d, PIF4 mRNA expression in Col-0, vil1-1, phyB-9 and vil1-1phyB-9 seedlings grown for 7 days at four different temperatures in SD. Samples were collected at both ZT0 (c) and ZT6 (d). The expression levels were normalized to that of PP2A and further normalized by the transcript level of Col-0 at ZT0, at 12°C. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates). The letters marked as same color above each bar indicate statistical difference between the genotypes at each temperature determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05). e, Immunoblot analysis showing that endogenous PIF4 protein levels are not changed by vil1. Proteins were extracted from seven-day-old seedlings grown in SD at ZT6. Endogenous tubulin levels were detected as controls by anti-tubulin antibody. The experiment was repeated at least two times independently with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 3. VIL1 inhibits the plant growth by repressing growth-promoting genes.

a - c, mRNA expression of ATHB2 (a), HFR1 (b) and PIL1 (c) in Col-0, vil1-1, phyB-9 and vil1-1phyB-9 seedlings grown for 7 days at four different temperatures in SD. Samples were collected at ZT6. The expression levels were normalized to that of PP2A and further normalized by the transcript level of Col-0 at ZT0, at 12°C shown in Fig. 1. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates). The letters marked as same color above each bar indicate statistical difference between the genotypes at each temperature determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05).

Extended Data Fig. 4. The expression of growth-promoting genes is dependent on PIF4.

a - c, mRNA expression of ATHB2 (a), HFR1 (b) and PIL1 (c) in Col-0 and pif4-2 seedlings grown for 7 days at 22°C in SD. Samples were collected both at ZT0 and at ZT6. The asterisks indicate significant difference (P < 0.05). d to f, mRNA expression of ATHB2 (d), HFR1 (e), and PIL1 (f) in Col-0, vil1-1, phyB-9, vil1-1 phyB-9, pif4-2, vil1-1 pif4-2, and vil1-1 phyB-9 pif4-2 seedlings grown for 7 days at 22°C in SD. Samples were collected at ZT0. The expression levels were normalized to that of PP2A and further normalized by the expression level of Col-0. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates). The letters above each bar indicate statistical difference between the genotypes determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05).

Extended Data Fig. 5. VIL1 alone does not regulate the expression of growth-promoting, hormone signaling genes.

a - d, mRNA expression of YUC8 (a, b) and IAA29 (c, d) in Col-0, vil1-1, phyB-9 and vil1-1phyB-9 seedlings grown for 7 days at four different temperatures in SD. Samples were collected at ZT0 (a, c) and ZT6 (b, d) respectively. The expression levels were normalized to that of PP2A and further normalized by the transcript level of Col-0 at ZT0, at 12°C. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates). The letters marked as same color above each bar indicate statistical difference between the genotypes at each temperature determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05).

Extended Data Fig. 6. VIL1 protein does not interact with PIF4 protein in vitro.

In vitro pull-down assay showing that MBP-VIL1 protein does not interact with GST-PIF4 proteins. MBP, MBP-VIL1 and MBP-SPA1 proteins were expressed in E. coli and purified using amylose-agarose beads. GST-PIF4 was also expressed in E. coli. Amylose-agarose bound MBP, MBP-VIL1 and MBP-SPA1 were used to pull-down different amount of purified GST-PIF4 protein. Pull-down samples were loaded 10% SDS-PAGE. GST-PIF4 was detected using anti-GST antibody, while the bait protein was visualized following Coomassie blue staining. The asterisks indicate each of MBP, MBP-VIL1 or MBP-SPA1 protein. The experiment was repeated at least two times independently with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 7. VIL1 and phyB directly regulate the expression of HFR1 and PIL1 by inducing H3K27me3 on their loci.

a and c, Hypocotyl length phenotype of VIL1 complementation lines (pVIL1:VIL1-myc/vil1-1 and pVIL1:VIL1-Flag/vil1-1) and another allele of vil1 mutant (vil1-2). The seedlings were grown for 7 days at 22°C in SD. A scale bar = 5 mm. b and d, Quantification data of hypocotyl length shown in a, n = 25 seedlings. The box plot boundaries reflect the interquartile range, the horizontal line is the median and the whiskers represent 1.5X the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles. The letters above each box indicate statistical difference between the genotypes determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05). e, ATHB2, HFR1 and PIL1 loci, G-box elements, ChIP-qPCR amplicons. The red vertical bars indicate G-box regions. RE1, RE2, RE, P1, and P2 indicate ChIP-qPCR amplicons. f, ChIP assay showing the relative enrichments of VIL1-myc in phyB-9 on ATHB2, HFR1, and PIL1 loci by comparing to enrichments of VIL1-myc at ZT0 and at ZT6. The ChIP assay used anti-myc antibody on seven days old seedlings grown at 22°C in SD. The immunoprecipitated DNA relative to input was further normalized to that of 5S rDNA. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 3, biological replicates. The asterisks indicate statistical difference in a two-tailed student t-test (P < 0.05). g, H3K27me3 levels in Col-0, vil1-1, phyB-9, vil1-1phyB-9, and pif4-2 at ZT6. This ChIP assay used anti-H3K27me3 antibody and anti-H3 antibody. The y axis indicates H3K27me3 enrichment relative to H3 enrichment (normalized by that of 5S rDNA). Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates). The asterisks indicate statistical differences in a two-tailed student t-test (P < 0.05). n.s. indicates not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 8. VIL1 protein is stabilized by light and VIL1 enrichment is dependent on phyB.

a and b Diurnally regulated VIL1-myc protein levels (a) and VIL1 mRNA levels (b). a, The seedlings of pVIL1:VIL1-myc/vil1-1 transgenic plants grown at 22°C in SD for 7 days were collected at eight different time points (ZT0 to ZT20). The VIL1-myc protein levels were detected by anti-myc antibody. Endogenous tubulin levels were detected as controls by anti-tubulin antibody. b, VIL1 mRNA levels in Col-0 seedlings grown at 22°C in SD for 7 days. Samples were collected at eight different time points (ZT0 to ZT20). The expression levels are normalized to that of PP2A. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates). c, VIL1-myc protein levels were stabilized in light. Four-day-old dark grown seedlings were either kept in the dark or treated with continuous red-light (10.7 μmol m−2 s−1) for the period indicated in the panel. Anti-myc and anti-RPT5 antibodies were used to detect VIL1-myc and RPT5 (control), respectively. d, Unchanged VIL1-myc protein levels in phyB-9 mutants. Proteins were extracted in the seedlings grown for 7 days at 22°C in SD at ZT6. In a, c and d, all experiments were repeated at least two times independently with similar results. e, FLC locus with ChIP-qPCR amplicons (P1 and P2). f, Similar enrichments of VIL1 on FLC locus between at ZT0 and at ZT6. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 3, biological replicates. g, ChIP assay showing that relative enrichments of VIL1-myc on ATHB2 are reduced in phyB-9 at ZT6. Error bars: ± s.d. n = 3, biological replicates. f and g, The ChIP assay used anti-myc antibody on seven days old seedlings grown at 22°C in SD. The immunoprecipitated DNA relative to input was further normalized to that of 5S rDNA. In f and g, the asterisks indicate statistical difference in a two-tailed student t-test (***P < 0.0005, *P < 0.05), n.s. indicates not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 9. PRC2 targets the growth-promoting genes.

The IGV views showing the enrichments of CLF-GFP and SWN-GFP, and H3K27me3 in WT, clf, swn and clf swn double mutants on ATHB2, HFR1 and PIL1 loci.

Extended Data Fig. 10. phyB coordinates with PRC2 through VIL1 to regulate its target genes.

a, Hypocotyl length of seedlings of each genotypes grown for 7 days at four different temperatures (12°C, 17°C, 22°C, and 27°C) in SD. Scale bar: 5 mm. b, Quantification of hypocotyl length, n = 20 seedlings. c, Hypocotyl length of seedlings of Col-0, vil1-1, vrn2, phyB-9, vil1-1 phyB-9, and vrn2 phyB-9 grown for 7 days at 22°C in SD, Scale bar: 5 mm, n = 20 seedlings. In b and c, the box plot boundaries reflect the interquartile range, the horizontal line is the median and the whiskers represent 1.5X the interquartile range from the lower and upper quartiles. The letters marked as same color above each box indicate statistical difference between the genotypes at each temperature determined by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05). d and e, Relative interaction frequency (RIF) in 3C assay between the Anchor primer and a series of F(forward) primers (d), or between the Anchor primer and a series of R(reverse) primers (e) in Col-0, and the vrn2 mutant at ZT6. The enrichment of each region was normalized to that of PP2A. These values were further normalized to the enrichment of each region in pATHB2:ATHB2-Flag plasmid DNAs. Error bars: ± s.d., n = 2, biological replicates (each biological replicate is an average value of four technical replicates). f and g, Model: A novel phyB regulatory module. f, phyB inhibits PIF4 by promoting its protein degradation and repression of DNA binding activity to repress the plant growth under the light. Our model shows a novel regulatory module in which the active form of phyB directly interacts with VIL1 to mediate chromatin remodeling at the growth-promoting genes by recruiting PRC2. Chromatin remodeling by the phyB-VIL1 module ensures the repression of growth-promoting genes, which otherwise can be activated by PIF4. g, On ATHB2 locus, active phyB forms a repressive chromatin loop with VIL1-PRC2. The presence of both phyB and VIL1 is important for the loop formation and for repressive H3K27me3 mark on this locus to fully inhibit ATHB2 expression. However, since neither phyB nor VIL1 can directly bind to DNA, it is possible that unknown DNA-binding protein (X) may be involved in phyB-VIL1 association with the target chromatin.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr. Richard Amasino and Dr. Keiko Torii for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH R01GM100108, NSF IOS 1656764 to S. S. and NSF MCB-2014408 to E. H.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Extended Data Sets. Additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1.Bae G & Choi G Decoding of light signals by plant phytochromes and their interacting proteins. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59, 281–311 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung JH et al. Phytochromes function as thermosensors in Arabidopsis. Science 354, 886–889 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Legris M, Ince YC & Fankhauser C Molecular mechanisms underlying phytochrome-controlled morphogenesis in plants. Nat Commun 10, 5219 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng MC, Kathare PK, Paik I & Huq E Phytochrome Signaling Networks. Annu Rev Plant Biol (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Lucia F, Crevillen P, Jones AM, Greb T & Dean C A PHD-polycomb repressive complex 2 triggers the epigenetic silencing of FLC during vernalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 16831–16836 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood CC et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana vernalization response requires a polycomb-like protein complex that also includes VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 14631–14636 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casal JJ, Luccioni LG, Oliverio KA & Boccalandro HE Light, phytochrome signalling and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Photochem Photobiol Sci 2, 625–636 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gommers CMM & Monte E Seedling Establishment: A Dimmer Switch-Regulated Process between Dark and Light Signaling. Plant Physiol 176, 1061–1074 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leivar P & Quail PH PIFs: pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci 16, 19–28 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee N & Choi G Phytochrome-interacting factor from Arabidopsis to liverwort. Curr Opin Plant Biol 35, 54–60 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park E et al. Phytochrome B inhibits binding of phytochrome-interacting factors to their target promoters. Plant J 72, 537–546 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung S, Schmitz RJ & Amasino RM A PHD finger protein involved in both the vernalization and photoperiod pathways in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 20, 3244–3248 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DH & Sung S Coordination of the vernalization response through a VIN3 and FLC gene family regulatory network in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 454–469 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aranda S, Mas G & Di Croce L Regulation of gene transcription by Polycomb proteins. Sci Adv 1, e1500737 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Mierlo G, Veenstra GJC, Vermeulen M & Marks H The Complexity of PRC2 Subcomplexes. Trends Cell Biol 29, 660–671 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Lucas M et al. Transcriptional Regulation of Arabidopsis Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 Coordinates Cell-Type Proliferation and Differentiation. Plant Cell 28, 2616–2631 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamieson K et al. Loss of HP1 causes depletion of H3K27me3 from facultative heterochromatin and gain of H3K27me2 at constitutive heterochromatin. Genome Res 26, 97–107 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim DH & Sung S Vernalization-Triggered Intragenic Chromatin Loop Formation by Long Noncoding RNAs. Dev Cell 40, 302–312 e304 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanzuolo C, Roure V, Dekker J, Bantignies F & Orlando V Polycomb response elements mediate the formation of chromosome higher-order structures in the bithorax complex. Nat Cell Biol 9, 1167–1174 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eagen KP, Aiden EL & Kornberg RD Polycomb-mediated chromatin loops revealed by a subkilobase-resolution chromatin interaction map. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 8764–8769 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kheradmand Kia S et al. EZH2-dependent chromatin looping controls INK4a and INK4b, but not ARF, during human progenitor cell differentiation and cellular senescence. Epigenetics Chromatin 2, 16 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunihiro A et al. Phytochrome-interacting factor 4 and 5 (PIF4 and PIF5) activate the homeobox ATHB2 and auxin-inducible IAA29 genes in the coincidence mechanism underlying photoperiodic control of plant growth of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol 52, 1315–1329 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi H & Oh E PIF4 Integrates Multiple Environmental and Hormonal Signals for Plant Growth Regulation in Arabidopsis. Mol Cells 39, 587–593 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernardo-Garcia S et al. BR-dependent phosphorylation modulates PIF4 transcriptional activity and shapes diurnal hypocotyl growth. Genes Dev 28, 1681–1694 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hornitschek P et al. Phytochrome interacting factors 4 and 5 control seedling growth in changing light conditions by directly controlling auxin signaling. Plant J 71, 699–711 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nieto C, Lopez-Salmeron V, Daviere JM & Prat S ELF3-PIF4 interaction regulates plant growth independently of the Evening Complex. Curr Biol 25, 187–193 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun J, Qi L, Li Y, Chu J & Li C PIF4-mediated activation of YUCCA8 expression integrates temperature into the auxin pathway in regulating arabidopsis hypocotyl growth. PLoS Genet 8, e1002594 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh E, Zhu JY & Wang ZY Interaction between BZR1 and PIF4 integrates brassinosteroid and environmental responses. Nat Cell Biol 14, 802–809 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xi Y, Park SR, Kim DH, Kim ED & Sung S Transcriptome and epigenome analyses of vernalization in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shu J et al. Genome-wide occupancy of histone H3K27 methyltransferases CURLY LEAF and SWINGER in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Direct 3, e00100 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeong J & Choi G Phytochrome-interacting factors have both shared and distinct biological roles. Mol Cells 35, 371–380 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y et al. A quartet of PIF bHLH factors provides a transcriptionally centered signaling hub that regulates seedling morphogenesis through differential expression-patterning of shared target genes in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 9, e1003244 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiorucci AS et al. PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR 7 is important for early responses to elevated temperature in Arabidopsis seedlings. New Phytol 226, 50–58 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz YB & Pirrotta V Polycomb silencing mechanisms and the management of genomic programmes. Nat Rev Genet 8, 9–22 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz YB, Kahn TG, Dellino GI & Pirrotta V Polycomb silencing mechanisms in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 69, 301–308 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sewalt RG et al. Selective interactions between vertebrate polycomb homologs and the SUV39H1 histone lysine methyltransferase suggest that histone H3-K9 methylation contributes to chromosomal targeting of Polycomb group proteins. Mol Cell Biol 22, 5539–5553 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Mager J, Schnedier E & Magnuson T The mouse PcG gene eed is required for Hox gene repression and extraembryonic development. Mamm Genome 13, 493–503 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuettengruber B, Chourrout D, Vervoort M, Leblanc B & Cavalli G Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax proteins. Cell 128, 735–745 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ciabrelli F & Cavalli G Chromatin-driven behavior of topologically associating domains. J Mol Biol 427, 608–625 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matharu N & Ahituv N Minor Loops in Major Folds: Enhancer-Promoter Looping, Chromatin Restructuring, and Their Association with Transcriptional Regulation and Disease. PLoS Genet 11, e1005640 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu C et al. Genome-wide analysis of chromatin packing in Arabidopsis thaliana at single-gene resolution. Genome Res 26, 1057–1068 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sasnauskas G, Kauneckaite K & Siksnys V Structural basis of DNA target recognition by the B3 domain of Arabidopsis epigenome reader VAL1. Nucleic Acids Res 46, 4316–4324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan L et al. The transcriptional repressors VAL1 and VAL2 recruit PRC2 for genome-wide Polycomb silencing in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res 49, 98–113 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim J et al. PIF1-Interacting Transcription Factors and Their Binding Sequence Elements Determine the in Vivo Targeting Sites of PIF1. Plant Cell 28, 1388–1405 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paik I et al. A phyB-PIF1-SPA1 kinase regulatory complex promotes photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun 10, 4216 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang W et al. Direct phosphorylation of HY5 by SPA kinases to regulate photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. New Phytol 230, 2311–2326 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee S, Paik I & Huq E SPAs promote thermomorphogenesis by regulating the phyB-PIF4 module in Arabidopsis. Development 147 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Extended Data Sets. Additional data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.