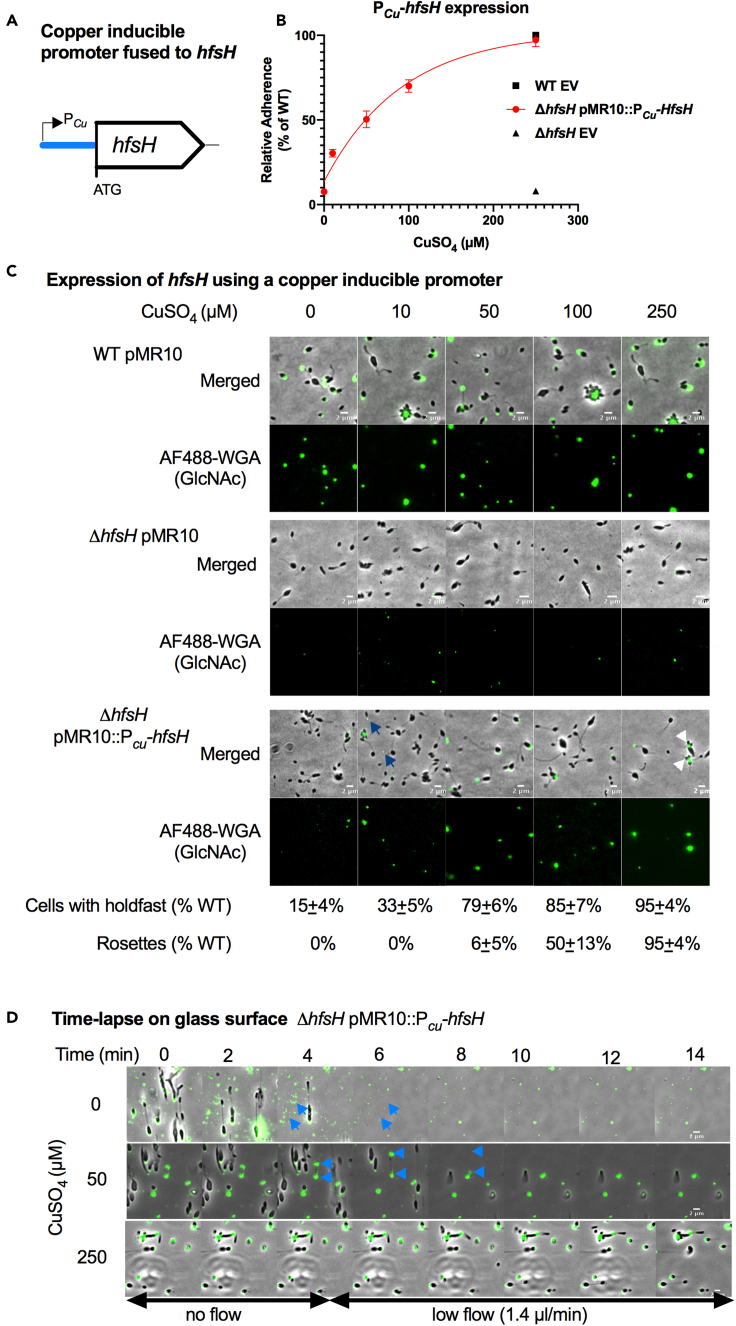

Figure 4.

HfsH expression correlates to the level of biofilm formation

(A) Schematic representation of hfsH under the control of a copper-inducible promoter. 500-bp upstream of the copA open reading frame corresponding to the promoter region, PCu, were fused to hfsH from H. baltica and assembled into the plasmid pMR10.

(B) A nonlinear regression plot showing quantification of adhesion of H. baltica strains induced with 0–250 μM of CuSO4 for 4 h by the crystal violet assay. Data are expressed as a mean percent of WT crystal violet staining from three independent biological replicates with four technical replicates. Error is expressed as the standard error of the mean. EV is empty vector (pMR10).

(C) Representative images of H. baltica WT, H. baltica ΔhfsH, and H. baltica ΔhfsH complemented with pMR10:PCu-hfsH. Holdfasts were labeled with AF488-WGA (green). Exponential cultures were induced for 2 h with 0–250 μM of CuSO4. Blue arrows indicate shed holdfast at low levels of induction (10 μM CuSO4), and white arrowheads indicate rosettes formed at high levels of HfsH induction (250 μM CuSO4). Scale bar, 2 μm.

(D) Time-lapse montages of H. baltica ΔhfsH pMR10:PCu-hfsH in microfluidic channels with holdfast labeled with AF488-WGA (green). Exponential cultures were induced with 0 μM, 50 μM, or 250 μM CuSO4, mixed with AF488-WGA, injected into the microfluidic chambers, and allowed to bind for 30 min. Thereafter, the flow rate was adjusted to 1.4 ul/min. Images were collected every 20 s for 1 h. Blue arrows indicate shed holdfasts. Scale bar, 2 μm. See also Videos S5, S6, and S7.