Abstract

The objective of this retrospective study was to evaluate the expression of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) in canine adrenal tumors and correlate this expression with features of tumor aggressiveness and survival in dogs undergoing adrenalectomy.

Forty-three canine adrenal tumors were evaluated for expression of c-kit, fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (flt-3), platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFR-β), and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) using immunohistochemistry. Tumor RTK staining characteristics were compared to normal adrenals. Medical records were reviewed for data regarding patient outcome and tumor characteristics. Expression of c-kit, flt-3, PDGFR-β, and VEGFR2 was detected in 26.9%, 92.3%, 96.2%, and 61.5% of cortical tumors and 0%, 63.2%, 47.4%, and 15.8% of pheochromocytomas, respectively. Expression of RTKs was not significantly increased when compared to normal adrenals and did not correlate with survival after adrenalectomy. Receptor tyrosine kinases are not overexpressed in canine adrenal tumors compared to normal adrenal tissue. Therapeutic inhibition of these receptors may still represent an effective approach in cases where receptor activation is present.

Résumé

L’objectif de cette étude rétrospective était d’évaluer l’expression des récepteurs tyrosine kinases (RTKs) dans les tumeurs surrénales canines et de corréler cette expression avec des caractéristiques d’agressivité tumorale et de survie chez les chiens subissant une surrénalectomie.

Quarante-trois tumeurs surrénales canines ont été évaluées pour l’expression de c-kit, de la tyrosine kinase 3 de type fms (flt-3), du récepteur du facteur de croissance dérivé des plaquettes-β (PDGFR-β) et du récepteur du facteur de croissance endothélial vasculaire 2 (VEGFR2) par immunohistochimie. Les caractéristiques de coloration de la tumeur RTK ont été comparées à celles des surrénales normales. Les dossiers médicaux ont été examinés pour les données concernant les résultats des patients et les caractéristiques de la tumeur. L’expression de c-kit, flt-3, PDGFR-β et VEGFR2 a été détectée dans 26,9 %, 92,3 %, 96,2 % et 61,5 % des tumeurs corticales et 0 %, 63,2 %, 47,4 % et 15,8 % des phéochromocytomes, respectivement. L’expression des RTK n’était pas significativement augmentée par rapport aux surrénales normales et n’était pas corrélée avec la survie après surrénalectomie. Les récepteurs tyrosine kinases ne sont pas surexprimés dans les tumeurs surrénales canines par rapport au tissu surrénalien normal. L’inhibition thérapeutique de ces récepteurs peut encore représenter une approche efficace dans les cas où l’activation du récepteur est présente.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Introduction

Adrenocortical carcinomas, adrenocortical adenomas, and pheochromocytomas are the most common primary adrenal tumors in dogs (1,2). Most adrenocortical tumors are functional and result in clinical signs secondary to hyperadrenocorticism, including polyphagia, polyuria, polydipsia, hair loss, and a pendulous abdomen (2–4). Pheochromocytomas also have the capacity to be hormonally active through the secretion of epinephrine and/or norepinephrine and can result in intermittent and often vague clinical symptoms, including anxiety, weight loss, neurologic abnormalities, and collapse, though many dogs are asymptomatic (5,6).

Surgery is considered the treatment of choice for canine adrenal tumors and dogs that survive the immediate post-operative period are expected to survive long-term. Median survival times from 22 to 48 mo have been reported following surgery alone (1–3,7). Unfortunately, adrenalectomy is still accompanied by a high risk of peri-operative mortality ranging from 12 to 31% (1–4,7–9). In some cases, surgery is not feasible due to large tumor size, extensive vascular invasion, or the presence of metastasis. Metastatic disease has been reported in 9 to 22% of dogs (2–4,7). Identifying effective adjuvant therapies may benefit some patients when surgery is not an option.

The receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor toceranib phosphate (Palladia; Zoetis, Parsippany, New Jersey, USA) is approved for the treatment of canine mast cell tumors and its effects are partially mediated by the inhibition of c-kit, a cell surface receptor involved in cellular proliferation, maturation, and differentiation (8–10). Toceranib has also been shown to inhibit a variety of other RTKs, including fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (flt-3), platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β (PDGFR-β), and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) (11–13). Toceranib phosphate has efficacy against numerous canine tumors, including those of neuroendocrine origin (12–14). A recent retrospective study reported that 1 of the 5 dogs receiving toceranib for pheochromocytomas experienced a partial response (PR) (15). In humans, overexpression of VEGFR2, but not c-kit or PDGFR, has been reported in pheochromocytomas (16,17).

The purpose of this study was to characterize the expression of c-kit, flt-3, PDGFR-β, and VEGFR2 in a cohort of naturally occurring canine adrenal tumors with the goal of identifying a rationale for the use of toceranib, or other RTK inhibitors, for the treatment of these tumors. In addition, clinical data were examined to identify prognostic factors for dogs with cortical and medullary adrenal tumors undergoing adrenalectomy and to determine if RTK expression was associated with features of tumor aggressiveness and survival.

Materials and methods

Medical records from The University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine’s Small Animal Hospital between January 2012 and March 2016 were searched to identify dogs diagnosed with adrenal tumors. Most patients had undergone surgery for adrenalectomy. One dog that was included in the study had an incidental adrenal cortical adenoma found on necropsy. This patient was not included in the clinical data analysis. Histological diagnoses were confirmed by 2 pathologists in all cases.

Twenty-six cortical tumor sections and 21 pheochromocytoma sections were examined for c-kit, flt-3, PDGFR-β, and VEGFR2. Only the primary adrenocortical tumors were evaluated, since samples with vascular invasion or metastasis were not present in this group. Sixteen pheochromocytomas from cut sections of the primary tumor and 3 sections from selected vascular invasive regions of previously examined tumors were analyzed. Two metastatic pheochromocytoma sections from the liver and mesentery were also examined in a patient in which the primary tumor itself was not available since it had been excised at another hospital several years before presentation at our institution. In total, 5 invasive or metastatic regions of pheochromocytoma and 16 primary pheochromocytoma tumor sections were evaluated. Receptor tyrosine kinase expression patterns were analyzed in all tumors and compared to 3 normal canine adrenal glands from patients euthanized for reasons unrelated to adrenal disease. In addition, 8 sections of adrenal cortex and 8 sections of adrenal medulla were evaluated from non-neoplastic portions of excised adrenal tissue adjacent to the tumors.

Immunohistochemistry

Antibodies against c-kit, PDGFR-β, and VEGFR2 used in our study had been previously validated for use in dogs (18–21). There were no available validated antibodies against flt-3 for immunohistochemistry at the time this study was being conducted. In order to confirm correct targeting for the flt-3 anti-human antibody, a BLAST search was initially performed and revealed a 95% sequence homology between the canine and human flt-3 genes. In addition, Western blotting (results not shown) was performed on canine GL-1 lymphoid cell lysate using the same antibody. The GL-1 cell line is known to be flt-3 positive based on a previous study by Suter et al (22). We confirmed that there is cross-reactivity between the anti-human antibody and the canine flt-3.

A paraffin block representative of each tumor was selected for immunohistochemistry. Sections were cut at 5 μm and deparaffinized using xylene and graded alcohols. Indirect immunohistochemical staining was performed using an indirect immunostaining protocol that employed primary antibodies against c-kit (1:200, ab32363; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), flt-3 (1:200, ab150599; Abcam), PDGFR-β (1:400, ab107169; Abcam), and VEGFR2 (1:100, ab2349; Abcam). Sections were treated with secondary reagents (VECTASTAIN Elite ABC Anti-Rabbit Kit, PK6101; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California, USA) and NovaRed as the chromogen (SK-4800; Vector Laboratories). Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed using Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris base, 1 mM EDTA solution, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9.0) in a 95°C water bath for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched using 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min. Internal and external positive controls (spleen, granulation tissue, and hemangiosarcoma) and negative controls [omission of primary antibody and/or inclusion of sections stained with anti-keratin antibody (1:200, ab9377; Abcam) were processed in parallel.

Samples were examined microscopically and intensity of immunostaining was scored in 5 representative fields at 400× magnification distributed within the tumor using a semi-quantitative scoring scheme (Table I). The percent positivity and staining intensity scores assigned to each tumor were averages of the scores recorded from 5 fields at 400× magnification. A tumor was considered to have positive expression of a given receptor if at least 1 to 24% of cells stained positive with a minimal staining intensity of 1 (26). High receptor expression was defined as having a percent positivity score of 3 or higher with any staining intensity.

Table I.

Immunohistochemistry staining grading protocol.

| Parameter average on 5 × 400× magnification fields | |

|---|---|

| Receptor expression | |

| 0 | < 1% positive |

| 1 | 1 to 25% positive |

| 2 | 26 to 75% positive |

| 3 | > 76% positive |

| Staining intensity | |

| 0 | No staining |

| 1 | Weak staining |

| 2 | Moderate staining |

| 3 | Intense staining |

| 4 | Very intense staining |

Clinical data analysis

Clinical data were reviewed retrospectively and the following information was gathered: signalment, weight, tumor type, maximum tumor diameter, presence of unilateral or bilateral tumors, vascular invasion, and the presence of metastasis at diagnosis. Follow-up information regarding date of death and patient status (if still alive) was obtained from medical records, records from primary care veterinarians, and when necessary, through telephone conversations with primary care veterinarians and owners.

Statistical analyses

Statistical testing was performed on commercial software using GraphPad Prism version 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). For immunohistochemistry data, c-kit, flt-3, PDGFR-β, and VEGFR2 expression scores and staining intensity scores were compared between tumor types (cortical versus medullary) using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Receptor expression was compared among the cortical tissue (carcinoma versus adenoma versus non-neoplastic cortical tissue) and medullary tissue (invasive/metastatic pheochromocytoma versus primary pheochromocytoma versus non-neoplastic medulla) using a the Kruskal-Wallis test with the Dunn’s multiple comparisons test for post-hoc analysis. The Spearman correlation was used to test for relationships between individual RTK expression and tumor diameter for all tumors. A contingency table was developed to compare RTK expression scores and tumor vascular invasion and differences were compared using the Fischer’s exact test. For dogs with 2 tumors, RTK expression for the larger tumor was used. Similarly, dogs that were diagnosed with 2 different adrenal tumor types were assigned the larger tumor type as their final diagnosis for outcome evaluation. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated and survival between groups was compared using the Logrank test. Dogs still alive were censored when they were last known to be alive and disease-free. Dogs that were known to have died of diseases unrelated to their adrenal tumor were censored from analysis at the date of death. Deceased dogs that did not have a known cause of death were considered dead of their adrenal disease. Significance was set to P < 0.05.

Results

Immunohistochemistry

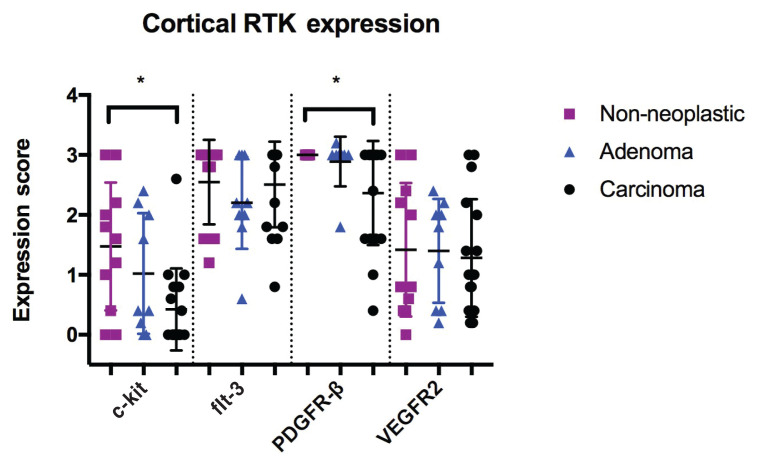

The expression patterns of adrenocortical tumors and normal adrenal tissue are characterized in Table II and Figure 1. Overall, RTK expression was moderate to high for cortical tumors and non-neoplastic cortical tissue. The average receptor staining intensity was weak for all examined receptors. In cortical adrenal tissue and tumors, receptor expression and staining intensity were greatest for PDGFR-β and flt-3. Receptor expression was not significantly different between carcinomas, adenomas, and normal adrenal tissue, however c-kit (P = 0.0211) and PDGFR-β (P = 0.0493) were significantly decreased in carcinomas compared to non-neoplastic tissue. No other differences were found when RTK expression was compared between carcinomas, adenomas, and non-neoplastic cortical tissue.

Table II.

Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) staining characteristics for cortical adrenal tissue and cortical tumors.

| Receptor | Tumors with RTK expression (%) | Tumors with high RTK expression (%) | Non-neoplastic cortical tissue with RTK expression (%) | Mean staining intensity score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-kit | 26.9 | 0 | 63.6 | 0.45 |

| flt-3 | 92.3 | 50 | 100 | 1.91 |

| PDGFR-β | 96.2 | 50 | 100 | 1.71 |

| VEGFR2 | 61.5 | 7.7 | 91 | 0.83 |

flt-3 — fms-like tyrosine kinase 3; PDGFR-β — platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β; VEGFR2 — vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

Figure 1.

RTK expression in canine cortical non-neoplastic tissue, adenomas, and carcinomas.

* — The difference was statistically significant.

Receptor tyrosine kinase expression patterns for non-neoplastic medullary tissue and pheochromocytomas are shown in Table III and Figure 2. Receptor expression was generally low to moderate for all examined tissue and staining intensity was weak for all receptor types. Expression of c-kit was not observed in any non-neoplastic or neoplastic tissue examined. When RTK expression was compared between non-neoplastic medullary tissue, pheochromocytomas, and selected regions of invasive and metastatic pheochromocytomas, no differences were observed except for significantly decreased expression of PDGFR-β in the invasive/metastatic sections of pheochromocytoma compared to primary pheochromocytoma sections (P = 0.0345) and non-neoplastic medullary tissue (P = 0.0080).

Table III.

Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) staining characteristics for canine medullary adrenal tissue and medullary tumors.

| Receptor | Tumors with RTK expression (%) | Tumors with high RTK expression (%) | Non-neoplastic medullary tissue with RTK expression (%) | Mean tumor intensity score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-kit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| flt-3 | 63.2 | 10.5 | 91 | 0.98 |

| PDGFR-β | 47.4 | 21 | 91 | 0.93 |

| VEGFR2 | 15.8 | 0 | 27.3 | 0.21 |

flt-3 — fms-like tyrosine kinase 3; PDGFR-β — platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β; VEGFR2 — vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

Figure 2.

RTK expression in canine non-neoplastic medullary tissue, pheochromocytomas, and invasive/metastatic pheochromocytomas.

** — The difference was statistically significant.

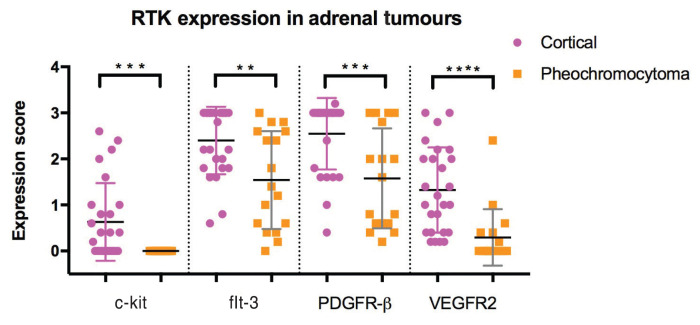

When RTK expression was compared between cortical tumors and medullary tumors, a significant decrease in expression for all receptor types was observed in medullary tumors (P < 0.03) (Figure 3). The staining intensity was also significantly decreased for medullary tumors compared to cortical tumors (P < 0.03).

Figure 3.

RTK Expression between cortical and medullary adrenal tumors.

**, ***, **** — The differences were statistically significant.

Survival, prognostic factors, and correlation of RTK expression with clinical characteristics

Six dogs died in the peri-operative period and 32 survived. Sixteen dogs were still alive at the time of writing and 20 dogs had died. The median survival time for all patients undergoing adrenalectomy was 944 d. There was no difference in survival found for any of the following parameters: tumor type (cortical adenoma, carcinoma, or pheochromocytoma), vascular invasion, maximum tumor diameter, or bilateral adrenal tumors.

Individual RTK expression was evaluated for correlations between the level of receptor expression and features of tumor aggressiveness, including size and vascular invasion, and no associations were found. There were also no associations discovered between individual RTK expression levels or staining intensity and adrenal-related mortality.

Discussion

Our study shows that overexpression of the 4 RTKs tested (c-kit, flt-3, PDGFR-β, and VEGFR2) is not present in canine adrenal tumors. In fact, significantly decreased expression of c-kit and PDGFR-β was observed in cortical carcinomas and decreased expression of PDGFR-β was observed in the invasive and metastatic sections of pheochromocytomas when compared to normal adrenal tissue. Differential expression of receptors was found between cortical tumors and pheochromocytomas, with cortical tumors displaying significantly increased RTK expression. Finally, features of tumor aggressiveness and overall survival were not correlated with RTK expression patterns. Classically, RTK inhibitors have been recommended for the direct inhibition of constitutively-activated or overexpressed RTKs, due to significantly increased drug efficacy. For example, canine cutaneous mast cell tumors are known to commonly harbor internal tandem duplications (ITD) in exon 11 of c-kit, which leads to constitutive activation of this receptor (8,23–25). In a prospective clinical trial where the c-kit mutational status was determined and correlated with the response to toceranib, 69% of dogs with exon 11 ITD developed an objective response compared to only 37% of patients with wild-type c-kit (12).

However, mutational activation or overexpression of RTKs is not a necessity for tumor response. This was demonstrated by the high biologic response rate seen in dogs with apocrine gland anal sac adenocarcinoma (AGASACA) and thyroid carcinoma treated with toceranib. Twenty-five percent of dogs with those tumors had a PR (9). Further molecular characterization of AGASACA and thyroid carcinomas revealed the presence of these receptors on an mRNA and a protein level, yet did not show phosphorylation of c-kit, PDGFRα/β, or VEGFR2 for either tumor (15). In the same study, phosphorylation of RET was observed in 54% of anal sacs and 20% of thyroid carcinomas. The authors concluded that the response seen in cases of AGASACA and thyroid carcinoma could have been due to the activity of toceranib on phosphorylated RET in tumor cells or on PDGFR and VEGFR in endothelial cells (15). By inhibiting activated RTKs in normal cells, toceranib may act primarily on the supporting endothelium and other cells of the tumor microenvironment rather than on the tumor itself. The primary mechanism of action in some cancers has been postulated to be via inhibition of VEGFR and PDGFR-β, leading to decreased angiogenesis (15,23) The objective response rates in dogs with AGASACA and thyroid carcinomas are comparable to the objective response rate of 37% reported for cutaneous mast cell tumors without c-kit mutations (12,14). The lack of RTK overexpression seen by us and in the above studies suggests that the results obtained by Musser et al (15) (20% PR) when treating dogs with pheochromocytoma, are reasonable. By using RTK inhibitors such as toceranib, the response rates for canine adrenal tumors are likely to be similar to other neoplasms in which RTK overexpression has not been observed.

Immunomodulation has been suggested as another possible effect of RTK inhibitors against tumors. Toceranib was suggested to cause downregulation of T-regulatory cells in a study that combined it with low doses of cyclophosphamide (24,26). In contrast, a more recent study, in which dogs with stage 3 osteosarcoma were treated with single-agent toceranib, did not reveal significant decreases in T-regulatory cells following treatment (26). Similarly, T-regulatory cell decreases were not observed in dogs treated with a combination of toceranib and doxorubicin (27). Currently, the ability of toceranib to downregulate T-regulatory cells is unclear, however, the possibility remains that toceranib may exert anti-neoplastic immune modulatory effects, which may contribute to a tumor response even in the absence of significant RTK overexpression.

The median survival time for patients undergoing adrenalectomy was 944 d, which is comparable to previous recent studies (1–7). There was no difference in survival found for any of the following parameters: tumor type (cortical adenoma, carcinoma, or pheochromocytoma), vascular invasion, maximum tumor diameter, bilateral adrenal tumors, or RTK expression. Some studies have suggested that there is an effect of tumor size and vascular invasion on survival. We agree that this is likely the case, but as in previous reports, our study did not consistently observe this effect (1–4). A meta-analysis with a large number of cases may finally be able to identify important prognostic factors.

Limitations of the current study include its retrospective nature and relatively small number of cases. In addition, the phosphorylation status of c-kit, flt-3, PDGFR-β, and VEGFR2 was not ascertained by our study, and such exploration may provide additional insight on the effectiveness of RTK inhibitors for the treatment of adrenal tumors in dogs.

In conclusion, some of the molecular targets of toceranib, including c-kit, flt-3, PDGFR-β, and VEGFR2, were not overexpressed in neoplastic adrenal tissue compared to non-neoplastic adrenal tissue and RTK expression may be significantly decreased in more aggressive tumors. Treatment with RTK inhibitors may still provide relatively modest responses due to inhibition of angiogenesis in the tumor microvasculature and surrounding microenvironment. This study also confirms that dogs undergoing adrenalectomy for adrenal tumors and surviving the immediate post-operative period are expected to have a long survival.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Elizabeth Whitely for supporting this study. Funds for this research were donated by Niko and Ms. Kathy Gehl.

References

- 1.Schwartz P, Kovak JR, Koprowski A, Ludwig LL, Monette S, Bergman PJ. Evaluation of prognostic factors in the surgical treatment of adrenal gland tumors in dogs: 41 cases (1999–2005) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;232:77–84. doi: 10.2460/javma.232.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrera JS, Bernard F, Ehrhart EJ, Withrow SJ, Monnet E. Evaluation of risk factors for outcome associated with adrenal gland tumors with or without invasion of the caudal vena cava and treated via adrenalectomy in dogs: 86 cases (1993–2009) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;242:1715–1721. doi: 10.2460/javma.242.12.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massari F, Nicoli S, Romanelli G, Buracco P, Zini E. Adrenalectomy in dogs with adrenal gland tumors: 52 cases (2002–2008) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;239:216–221. doi: 10.2460/javma.239.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyles AE, Feldman EC, De Cock HE, et al. Surgical management of adrenal gland tumors with and without associated tumor thrombi in dogs: 40 cases (1994–2001) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;223:654–662. doi: 10.2460/javma.2003.223.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilson SD, Withrow SJ, Wheeler SL, Twedt DC. Pheochromocytoma in 50 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 1994;8:228–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1994.tb03222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barthez PY, Marks SL, Woo J, Feldman EC, Matteucci M. Pheochromocytoma in dogs: 61 Cases (1984–1995) J Vet Intern Med. 1997;11:272–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.1997.tb00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson CR, Birchard SJ, Powers BE, Belandria GA, Kuntz CA, Withrow SJ. Surgical treatment of adrenocortical tumors: 21 cases (1990–1996) J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2001;37:93–97. doi: 10.5326/15473317-37-1-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.London CA, Kissebirth WC, Galli SJ, Geissler EN, Helfand SC. Expression of stem cell factor receptor (c-kit) by the malignant mast cells from spontaneous canine mast cell tumours. J Comp Pathol. 1996;115:399–414. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(96)80074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.London CA, Hannah AL, Zadovoskaya R, et al. Phase I dose-escalating study of SU11654, a small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in dogs with spontaneous malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2755–2768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pryer NK, Lee LB, Zadovaskaya R, et al. Proof of target for SU11654: Inhibition of KIT phosphorylation in canine mast cell tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5729–5734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.London C, Mathie T, Stingle N, et al. Preliminary evidence for biologic activity of toceranib phosphate (Palladia(®)) in solid tumors. Vet Comp Oncol. 2012;10:194–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2011.00275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.London CA, Malpas PB, Wood-Follis SL, et al. Multi-center, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized study of oral toceranib phosphate (SU11654), a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of dogs with recurrent (either local or distant) mast cell tumor following surgical excision. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3856–3865. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urie BK, Russell DS, Kisseberth WC, London CA. Evaluation of expression and function of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, platelet derived growth factor receptors-alpha and-beta, KIT, and RET in canine apocrine gland anal sac adenocarcinoma and thyroid carcinoma. BMC Vet Res. 2012;8:67. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-8-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown RJ, Newman SJ, Durtschi DC, Leblanc AK. Expression of PDGFR-β and Kit in canine anal sac apocrine gland adenocarcinoma using tissue immunohistochemistry. Vet Comp Oncol. 2012;10:74–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2011.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musser ML, Taikowski KL, Johannes CM, Bergman PJ. Retrospective evaluation of toceranib phosphate (Palladia®) use in the treatment of inoperable, metastatic, or recurrent canine pheochromocytomas: 5 dogs (2014–2017) BMC Vet Res. 2018;14:272. doi: 10.1186/s12917-018-1597-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassol CA, Winer D, Liu W, Guo M, Ezzat S, Asa SL. Tyrosine kinase receptors as molecular targets in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:1050–1062. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch CA, Gimm O, Vortmeyer AO, et al. Does the expression of c-kit (CD117) in neuroendocrine tumors represent a target for therapy? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1073:517–526. doi: 10.1196/annals.1353.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alfaleh MA, Arora N, Yeh M, et al. Canine CD117-specific antibodies with diverse binding properties isolated from a phage display library using cell-based biopanning. Antibodies (Basel) 2019;8:15. doi: 10.3390/antib8010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee KI, Olmer M, Baek J, D’Lima DD, Lotz MK. Platelet-derived growth factor-coated decellularized meniscus scaffold for integrative healing of meniscus tears. Acta Biomater. 2018;76:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welt FGP, Gallegos R, Connell J, et al. Effect of cardiac stem cells on left-ventricular remodeling in a canine model of chronic myocardial infarction. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:99–106. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.972273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song JH, Hwang TS, Lee HC, et al. Long-term management of canine disseminated granulomatous meningoencephalitis with imatinib mesylate: A case report. Vet Med (Praha) 2019;64:92–99. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suter SE, Small GW, Seiser EL, Thomas R, Breen M, Richards KL. FLT-3 mutations in canine acute lymphocytic leukemia. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downing S, Chien MB, Kass PH, Moore PE, London CA. Prevalence and importance of internal tandem duplications in exons 11 and 12 of c-kit in mast cell tumors of dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2002;63:1718–1723. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2002.63.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozao-Choy J, Ma G, Kao J, et al. The novel role of tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the reversal of immune suppression and modulation of tumor microenvironment for immune-based cancer therapies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2514–2522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell L, Thamm DH, Biller BJ. Clinical and immunomodulatory effects of toceranib combined with low-dose cyclophosphamide in dogs with cancer. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26:355–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laver T, London CA, Vail DM, Biller BJ, Coy J, Thamm DH. Prospective evaluation of toceranib phosphate in metastatic canine osteosarcoma. Vet Comp Oncol. 2018;16:E23–E29. doi: 10.1111/vco.12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellin MA, Wouda RM, Robinson K, et al. Safety evaluation of combination doxorubicin and toceranib phosphate (Palladia®) in tumour bearing dogs: A phase I dose-finding study. Vet Comp Oncol. 2017;15:919–931. doi: 10.1111/vco.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]