Abstract

Background

With the new pandemic reality that has beset us, teaching and learning activities have been thrust online. While much research has explored student perceptions of online and distance learning, none has had a social laboratory to study the effects of an enforced transition on student perceptions of online learning.

Purpose

We surveyed students about their perceptions of online learning before and after the transition to online learning. As student perceptions are influenced by a range of contextual and institutional factors beyond the classroom, we expected that students would be overall sanguine to the project given that access, technology integration, and family and government support during the pandemic shutdown would mitigate the negative consequences.

Results

Students overall reported positive academic outcomes. However, students reported increased stress and anxiety and difficulties concentrating, suggesting that the obstacles to fully online learning were not only technological and instructional challenges but also social and affective challenges of isolation and social distancing.

Conclusion

Our analysis shows that the specific context of the pandemic disrupted more than normal teaching and learning activities. Whereas students generally responded positively to the transition, their reluctance to continue learning online and the added stress and workload show the limits of this large scale social experiment. In addition to the technical and pedagogical dimensions, successfully supporting students in online learning environments will require that teachers and educational technologists attend to the social and affective dimensions of online learning as well.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Approach to learning, Online teaching, Online learning, e-learning

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 or Covid-19 (Fauci, Lane, & Redfield, 2020) or SARS-CoV-2 (Velavan & Meyer, 2020) pandemic outbreak has disrupted and changed how we socialize, work, and learn (Brynjolfsson et al., 2020; Daniel, 2020; Haase, Cosco, Kervin, Riadi, & O'Connell, 2021; Gonzalez et al., 2020). Since the pandemic began, much human activity has transitioned online (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020; Kramer & Kramer, 2020). The profound effects of the pandemic are being especially felt in education (Marinoni, Land, & Jensen, 2020; Schleicher, 2020; Stambough et al., 2020). For education, the pandemic is both a challenge (Daniel, 2020) and an opportunity (Azorín, 2020). Schools have closed to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 (Pokhrel & Chhetri, 2021) and the Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted traditional models of learning (Lemay and Doleck, 2020) and precipitated a move to online teaching and learning activities (Lemay, Doleck, & Bazelais, 2021). In the wake of the pandemic, most institutions of higher education have had to reconsider ways of teaching and assessment (García-Peñalvo, Corell, Abella-Garcí).

Regarding teaching, this abrupt transition “has led to significantly intensified workloads for staff as they work to not only move teaching content and materials into the online space, but also become sufficiently adept in navigating the requisite software” (Allen et al., 2020, Allen et al., 2020, p. 233). Likewise, students faced difficulties and challenges adapting to the abrupt and unplanned shift to online learning (Baticulon et al., 2021). In fact, it is not surprising that we know little about students’ readiness for real-time online learning (Tang et al., 2021). Previous research on online teaching and learning has generally shown that transitions are usually voluntary and/or planned; however, emergency transitions, such as the one brought upon by the Covid-19 pandemic, have relatively little body of knowledge (García-Peñalvo et al., 2021, García-Peñalvo et al., 2021; Iglesias-Pradas, Hernández-García, Chaparro-Peláez, & Prieto, 2021; Lemay et al., 2021). Considering this significant upheaval, we wanted to explore how these changes might influence student perceptions of online learning.

In this context it is important to understand student perceptions, to be able to develop successful interventions and correct deficits in learning. Examining student perceptions of online learning through the transition helps us to understand the limits and the potential of this mode of distance learning, and help to anticipate and adapt the effects of this sudden transition to online instruction.

2. Background

According to Kauffman (2015), “students perceive online courses differently than traditional courses” (p.1). In a highly cited paper Song, Singleton, Hill, and Koh (2004) conducted a large-scale study of graduate student perceptions of online learning and found a mix of facilitating and discouraging factors. Students felt that course design was an important factor that distinguished successful from unsuccessful online learning experiences. A review by Nora and Snyder (2008) documented mixed evidence for improved learning outcomes for online learning over traditional classes as technical problems were a significant impediment, including user proficiency with technology but also time management and maintaining interest and motivation online. It is unclear to what extent a forced and precipitated transition to online learning might affect perceptions of online learning.

Some research suggests that students may perform differently across different modalities, and some may even perform better in online learning environments (Cole et al., 2017; Fendler, Ruff, & Shrikhandle, 2018; Kurucay & Inan, 2017). Cole, Lennon, and Weber (2019) investigated the relationship between student perceptions of online learning practices, social belonging, and the learning climate, controlling for age and gender. They argue that successful online learning addresses the social dimension, to counter the absence and overcome the distance. They concluded that a successful fully online learning experience necessitates exploiting active learning strategies to create opportunities for connection and exchange. Indeed, there is research reporting that students are more appreciative of active learning strategies in online learning environments (Cole, Lennon, and Weber, 2019; Gómez-Rey, Barbera, & Fernández-Navarro, 2017; Koohang, Paliszkiewicz, Klein, & Nord, 2016).

It is acknowledged in the literature that online learning presents a learning environment that is distinct from face-to-face or classroom learning environments (Bazelais, Doleck, & Lemay, 2018). Students generally have favorable perceptions of online learning although they have reservations around technological proficiency and adequate course designs (Song et al., 2004). According to a recent review by Pokhrel and Chhetri (2021), “broadly identified challenges with e-learning are accessibility, affordability, flexibility, learning pedagogy, life-long learning and educational policy” (p. 4). Anecdotally, many distance learning programs are successful and students have thrived when they have been adequately supported. However, the unequal social outcomes and deprivations of the pandemic means many students have been deprived of adequate educational support (Flack, Walker, Bickerstaff, & Margetts, 2020). Many educationalists are lamenting the lost years of the pandemic and the lamentable effects for youth social development (Allen, Mahamed, & Williams, 2020). Thus, it is not clear how an enforced transition to remote teaching might influence student perceptions of online learning.

3. Purpose of the study

We sought to explore how the pandemic influenced student perceptions of online learning.

3.1. Research question

We asked “How did the pandemic and the unprecedented institution wide transition to remote delivery of instruction influence student perceptions of online learning in terms of access, engagement and academic progress?

4. Method

4.1. Design

We employed a cross-sectional survey-based design to gauge student perceptions of online learning before, during, and after the transition to remote instruction. We surveyed students at a college in Northeastern North America about their experience of the transition to online learning. Then, we compared and contrasted our findings with the empirical research to describe how student perceptions of online learning were influenced by the wholesale transition to online learning.

4.2. Procedure and participants

Participants completed an online survey during the middle months of 2020.Survey responses were collected online. Surveys were completed on a voluntary basis and were completely anonymous. The survey included questions related to the effects of transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.A total of N = 149 students from a pre-university science program at an English Collège d'enseignement général et professionnel (CEGEP; for a review, see Bazelais, Lemay, & Doleck, 2016) participated in the study. A breakdown of the participant characteristics is provided in Table 1 .

Table 1.

General characteristics of the respondents.

| Student Characteristics | N | M | SD | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18.17 | 0.94 | |||

| Gender | Female | 81 | 54.36 | ||

| Male | 66 | 44.30 | |||

| Other | 2 | 1.34 |

4.3. Measures

We used items from an existing questionnaire (Motz et al., 2020) adapted for the present context, focusing on student perceptions after the transition and assessing student reactions, and their perceptions of the impact of the transition on academic outcomes. We supplemented the Likert scale items with the following open-ended questions:

-

1.

What one thing could the College have done to improve your experience after the transition to online instruction?

-

2.

Reflecting on your transition to online instruction, what was the most negative outcome?

-

3.

Reflecting on your transition to online instruction, what was the most positive outcome?

-

4.

What one thing could your instructors have done to improve your experience after the transition to online instruction?

-

5.

Is there anything else that you feel is important regarding your experience with the transition to online learning that you would like to share?

5. Analysis

5.1. Background

We summarized the results and calculated descriptive statistics. We analyzed tendencies to provide a holistic picture of student perceptions of online throughout the transition. Open-ended questions were summarized using thematic analysis to inductively group answers into categories.

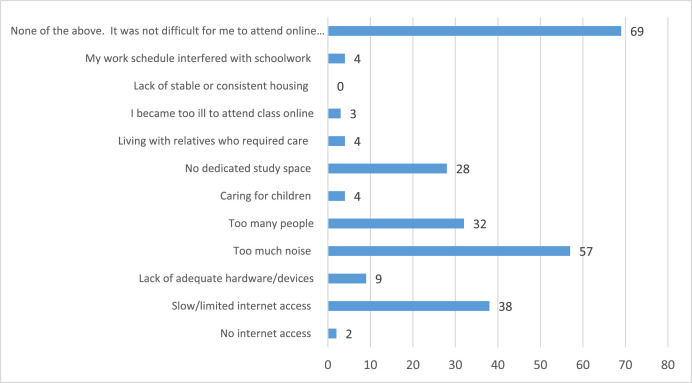

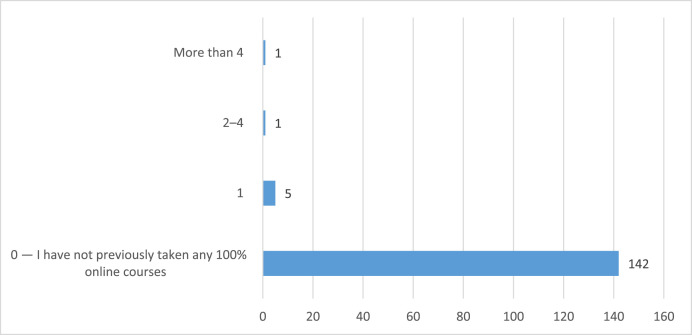

Of the 149 students surveyed, 45 were employed prior to COVID-19, but then unemployed due to COVID-19. 28 continued to be employed throughout the Winter 2020 semester. 76 reported no employment during this period. This is unsurprising as nearly all the students surveyed were still living with their parents, save one student who reported living alone. Fig. 1 presents student living situations prior to the pandemic. Students reported difficulty finding adequate study space, due to interruptions from too many people, not having space, and too much noise. Fig. 4 shows that 95% had not taken an online course prior to the pandemic. When the Winter 2020 semester began, only nine students were taking courses fully online or in a blended learning situation (a hybrid model, mixing both online and face-to-face components). 90% of students were not taking any online courses. However, over a third were registered in at least one blended learning course. Please see Table 2 for the frequency of online, blended, and face-to-face courses reported by students. Virtually none of the students surveyed had taken fully online courses prior to the wholesale transition to remote instruction.

Fig. 1.

Student living situation prior to pandemic.

Fig. 4.

Student experience of online learning prior to pandemic.

Table 2.

Winter course registration by delivery model prior to the transition to online learning.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Originally 100% online class (es) | 134 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Originally hybrid (blended-learning) class (es) | 94 | 48 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Originally face-to-face class (es) | 9 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 13 | 29 | 88 |

*fully-online courses (100% online), hybrid courses (with some face-to-face and some online sessions), or face-to-face courses (with all sessions physically face-to-face).

In Table 3 , we summarize student responses regarding levels of food or monetary insecurity in the earlier months of the pandemic. Whereas the pandemic was undeniably disruptive in everyone's lives, some were hit harder than others. Even for a relatively affluent population, food insecurity was an issue for a few. Signaling that despite governmental measures, some students were still facing hardships at home.

Table 3.

Student levels of food and money insecurity.

| Often true | Sometimes true | Never true | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within the past month, I worried whether my food would run out before I got money to buy more. | 1 | 8 | 140 |

| Within the past month, the food I bought just did not last and I did not have money to get more. | 0 | 5 | 144 |

5.2. Technology details

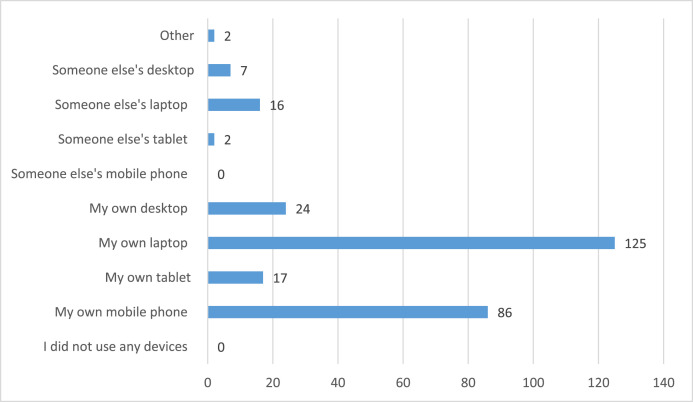

In Table 4 , we summarize student responses concerning their access to technology and their preparation for online learning. Fig. 2 illustrates students’ principal mode of connecting to online learning resources. Over 85% had access to the necessary computer equipment and Internet access, though 10% struggled with Internet connectivity and 5% did not have adequate computer hardware. Whereas the majority felt sufficiently prepared, 15% were unprepared which increased to a worrying 40% when accounting for those who were mitigated. Hence, material issues of technology and access were not important factors for the majority of students surveyed.

Table 4.

Student access to technology and preparation for online learning.

| Statement | Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Neither either or disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I had adequate access to the internet connectivity necessary to participate in online instruction. | 5.37 | 4.70 | 4.70 | 32.21 | 53.02 | 4.23 | 1.097 |

| I had adequate access to computer hardware necessary to participate in online instruction. | 3.36 | 2.68 | 2.01 | 26.85 | 65.10 | 4.48 | 0.927 |

| I was prepared for online instruction. | 6.04 | 9.40 | 24.83 | 34.23 | 25.50 | 3.64 | 1.140 |

Fig. 2.

Student internet connected device for online learning.

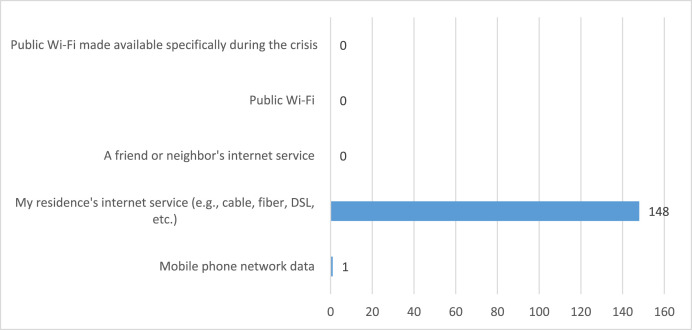

As can be seen in Fig. 2, over 85% reported using their own laptop. Surprisingly, more than half reported working on their smartphone at least part of the time. Given that a smartphone has become a necessary part of life, for many it is their only connected device or their only device at all. If one has to choose between a smartphone or a laptop, the laptop is the greater luxury and often the loser in the cost benefit analysis. Still a few reported having to share equipment to participate in online learning activities. This is concerning since it is largely accepted as a matter of course that everyone is connected these days. Yet for a minority, access remains uncertain or variable. Virtually everyone surveyed reported having an internet connection at home though at least 10% reported poor Internet connectivity. In Fig. 3 , we observe that virtually all students connected using their residence's internet services.

Fig. 3.

Primary method of connecting to the internet.

5.3. Engagement

This section of the survey addresses how the shift to online instruction impacted student engagement at college and in their courses. As can be observed in Table 5, Table 6 , the transition did lead to disaffection for many. Although most continued to identify as students, their academic goals became less important. 25% felt they were unsuccessful as a result of the transition to online learning even though 50% still found success in the transition.

Table 5.

Consequence of transition on student engagement in college and in class.

| Statement | Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Neither either or disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I still found it easy to think of myself as a college student. | 6.76 | 13.51 | 28.38 | 33.11 | 18.24 | 3.43 | 1.14 |

| I became less concerned about what my classmates and instructors thought of me. | 2.05 | 12.33 | 32.88 | 39.04 | 13.70 | 3.50 | 0.95 |

| I felt like I lost touch with the College community. | 2.70 | 6.08 | 20.27 | 46.62 | 24.32 | 3.84 | 0.96 |

| My academic goals became less important to me. | 16.89 | 26.35 | 14.19 | 27.70 | 14.86 | 2.97 | 1.35 |

| I felt I was successful as a college student. | 4.73 | 19.59 | 23.65 | 37.84 | 14.19 | 3.37 | 1.10 |

| I encountered discrimination or racism in my online instruction environment that had a negative impact on my learning. | 80.41 | 13.51 | 5.41 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 1.26 | 0.59 |

Table 6.

Consequence of transition on teaching and learning.

| Statement | Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Neither either or disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I found my coursework more challenging. | 7.43 | 22.97 | 22.97 | 29.73 | 16.89 | 3.26 | 1.20 |

| My instructor was more available for support. | 2.03 | 12.84 | 40.54 | 29.73 | 14.86 | 3.43 | 0.96 |

| I interacted with my classmates more. | 37.16 | 38.51 | 18.24 | 6.08 | 0.00 | 1.93 | 0.89 |

| I missed more course announcements than usual. | 10.14 | 35.14 | 20.95 | 25.00 | 8.78 | 2.87 | 1.16 |

| I earned lower grades than I expected. | 14.86 | 34.46 | 20.27 | 21.62 | 8.78 | 2.75 | 1.21 |

| It took more effort to complete my coursework. | 5.41 | 18.24 | 14.86 | 35.81 | 25.68 | 3.58 | 1.21 |

| It was harder to meet deadlines. | 7.43 | 39.19 | 17.57 | 21.62 | 14.19 | 2.96 | 1.22 |

| I had a better understanding of the learning goals. | 10.14 | 31.76 | 45.27 | 10.81 | 2.03 | 2.63 | 0.88 |

| I spent more time on my schoolwork overall. | 10.81 | 15.54 | 22.30 | 30.41 | 20.95 | 3.35 | 1.27 |

In Table 6, students were asked to think about their specific experience of one of three physics courses from Winter 2020, after courses transitioned to online instruction. Overall, students reported increased workload and more challenging work but also increased teacher support, however they also reported poorer communication, less understanding of course goals and less interaction with their peers.

5.4. Reaction

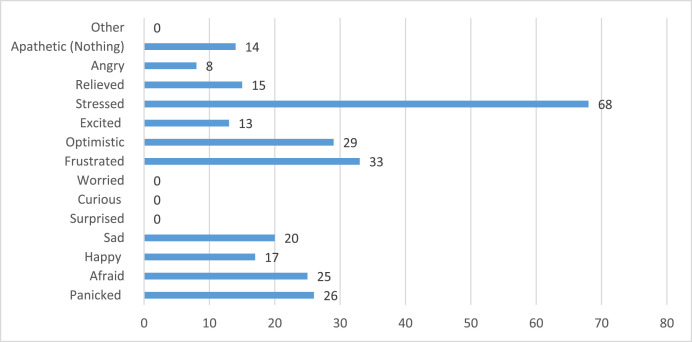

The following section deals with student reaction to the pandemic and its effects on instruction. As we can clearly see, the pandemic provoked a lot of stress and anxiety in students (see Fig. 5 ). Paradoxically, some were happy or optimistic, perhaps driven by the “reset” that was discussed in the early days of the pandemic where we might reflect socially in our collective relationship to work and to each other. Whereas students struggled with self-discipline in online learning, they remained optimistic and motivated to achieve their goals and this did not appear dampened by the transition to online learning.

Fig. 5.

Student affect response to pandemic.

Although students experienced a higher incidence of stress or anxious emotions on average, a few were opportunistic and even excited at the prospect of moving to online learning as we can see in Table 7 . This is perhaps explainable by the fact that one third did not feel they had sufficient self-discipline to be successful at fully online learning. However, majority of the students reported feeling positive about their diligence. Indeed, that they had grown from the experience and that they expected to be rewarded for their hard work.

Table 7.

Student performance self-assessment of online learning during pandemic.

| Statement | Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Neither either or disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I do not have the self-discipline to be successful in a completely online environment. | 15.65 | 31.29 | 19.05 | 26.53 | 7.48 | 2.79 | 1.21 |

| During the period of online learning, I feel that I experienced personal growth. | 5.48 | 19.18 | 36.99 | 30.14 | 8.22 | 3.16 | 1.00 |

| I have the inner drive to achieve my goals. | 2.76 | 11.03 | 22.07 | 44.83 | 19.31 | 3.67 | 1.00 |

| I sometimes let others limit my success. | 10.96 | 32.88 | 34.93 | 20.55 | 0.68 | 2.67 | 0.94 |

| I am diligent and will finish what I start. | 0.68 | 6.16 | 12.33 | 58.90 | 21.92 | 3.95 | 0.81 |

| I believe I will be rewarded for my hard work. | 4.79 | 10.27 | 17.81 | 47.95 | 19.18 | 3.66 | 1.05 |

5.5. Standards outcomes

Table 8 describes how students felt the transition impacted the standards and outcomes of their courses. Overall, students did not perceive academic misconduct had increased. Although it was felt that teachers relaxed their standards somewhat, the majority believed that their grades accurately reflected their performance.

Table 8.

Student perceptions of academic standards and outcomes in online learning during pandemic.

| Statement | Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Neither either or disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic misconduct increased among my classmates. | 12.24 | 30.61 | 35.37 | 15.65 | 6.12 | 2.73 | 1.06 |

| My instructor was not as concerned about cheating. | 28.57 | 34.69 | 21.77 | 12.24 | 2.72 | 2.26 | 1.09 |

| My instructor relaxed his/her standards (e.g., for grading, participation, deadlines, attendance, etc.) | 8.84 | 21.77 | 26.53 | 35.37 | 7.48 | 3.11 | 1.10 |

| My instructor should have been more concerned about cheating. | 19.73 | 27.89 | 42.86 | 6.80 | 2.72 | 2.45 | 0.97 |

| The grades I received accurately reflected how much I had learned. | 3.40 | 17.69 | 23.13 | 43.54 | 12.24 | 3.44 | 1.03 |

5.6. Academic progress

In this section, we asked how students believed the transition to online instruction impacted their academic progress and future plans. Overall students appeared sanguine about the effects of the pandemic. As can be seen in Table 9 , many felt they were on pace to graduate. Most did not feel that they had been negatively impacted by the transition to online learning. Although one quarter did feel they had been held back in their academic progress due to the transition to online learning.

Table 9.

Student perceptions of academic progress in online learning during the pandemic.

| Statement | Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Neither either or disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In terms of my academic progress, I feel that I am still on pace to meet my academic goals as scheduled. | 5.48 | 12.33 | 19.86 | 41.78 | 20.55 | 3.60 | 1.11 |

| I will be a better student than I was before the transition to online instruction. | 8.16 | 27.21 | 37.41 | 19.73 | 7.48 | 2.91 | 1.04 |

| I am more likely to enroll in a 100% online course now than I was before the transition to online instruction. | 29.25 | 29.25 | 21.77 | 13.61 | 6.12 | 2.38 | 1.21 |

| I anticipate being behind in my academic progress upon return to the classroom. | 14.97 | 29.25 | 26.53 | 25.17 | 4.08 | 2.74 | 1.11 |

| I will have to delay graduation or employment opportunities because I was not able to complete essential coursework or practical experiences during the Winter 2020 | 44.22 | 38.10 | 12.24 | 3.40 | 2.04 | 1.81 | 0.92 |

5.7. Learning

In Table 10 we asked how students believed the transition to online instruction impacted their ability to learn. Students painted a somewhat bleaker picture of online learning, as many as one in three struggled with online discussions. While most appreciated the ability to replay videos, nearly two thirds found it very difficult to focus on online lectures.

Table 10.

Student Perceptions of Transition's Impact on their Ability to Learn.

| Statement | Strongly Disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Neither either or disagree (%) | Agree (%) | Strongly Agree (%) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I had access to the same software that I was using on campus. | 0.68 | 14.29 | 4.08 | 54.42 | 26.53 | 3.92 | 0.97 |

| I benefited from being able to replay video lectures. | 2.72 | 11.56 | 14.29 | 37.41 | 34.01 | 3.88 | 1.08 |

| I struggled with the use of online discussions. | 8.11 | 31.08 | 21.62 | 31.08 | 8.11 | 3.00 | 1.13 |

| I was able to focus more clearly on the lectures without the distraction of other people. | 31.76 | 31.76 | 22.97 | 8.11 | 5.41 | 2.24 | 1.14 |

5.8. Qualitative analysis

In addition to the Likert scale questions, students were also asked five open-ended questions. Answers were inductively coded into thematic groupings and are summarized in Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, Table 14, Table 15 below. Student open-ended answers are aligned with their responses to the Likert question items. Their answers manifest their concerns for organization, communication, and technological support for effective online learning. They especially call for standards in delivery of online instruction. Students would have liked teachers to be more understanding about the their needs and the obstacles and challenges posed by the pandemic. Students also highlighted the specific challenges of this wholesale transition to online learning: technological shortcomings or lack of support, and perceptions of increased workloads, less interactions, poorer communication, and more overall confusion. Students called for varying instruction and employing a greater range of instructional tools and strategies, and most importantly for increased interactions, whether by making more use of group chats, collectively worked problems on virtual whiteboards, and flipping the classroom by assigning lectures and using class time to discuss problems. Many students called for recording lectures so they could be consulted later.

Table 11.

What one thing could the College have done to improve your experience after the transition to online instruction?.

| Thematic Category | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Nothing | 37 |

| Good | 9 |

| Bad | 2 |

| Don't know | 6 |

| Better organization | 8 |

| No evaluations | 4 |

| Recorded lectures | 11 |

| Better communication | 12 |

| Better student adaptations | 3 |

| Better technological support | 5 |

| Institution wide policies | 15 |

| Less coursework | 9 |

| Something better | 1 |

| Better enforcement of classroom behavior | 1 |

| Loosen deadlines | 1 |

| Better preparation | 3 |

| Better communication | 3 |

| Cancel the semester | 1 |

| Return to face-to-face learning | 1 |

| Include results in GPA | 3 |

| More flexibility | 3 |

| Smoother transition | 2 |

| More classroom interactions | 7 |

| More effective instruction | 4 |

| Maintain service quality | 1 |

Table 12.

Reflecting on your transition to online instruction, what was the most negative outcome?.

| Thematic Category | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Distractions | 12 |

| Demotivation | 40 |

| Poor performance | 9 |

| Poor instruction | 2 |

| Social isolation | 6 |

| Increased workload | 12 |

| Stress | 7 |

| Financial problems | 1 |

| Nothing | 11 |

| Too much screen time | 4 |

| Social isolation | 2 |

| Teacher suspicions of student misconduct | 1 |

| Planning | 1 |

| Less effective learning | 2 |

| Grades not included in GPA | 12 |

| Evaluation | 1 |

| Less effective learning | 12 |

| Less classroom interaction | 4 |

| Poor performance | 1 |

| increased workload | 8 |

| Communication issues | 5 |

| Trouble concentrating | 11 |

| Technical issues | 6 |

| Lack of flexibility | 1 |

| Lack of institution wide policies | 1 |

| Cheating | 1 |

Table 13.

Reflecting on your transition to online instruction, what was the most positive outcome?.

| Thematic Category | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Became more organized | 1 |

| Less stress | 12 |

| Better performance | 9 |

| Later start time | 11 |

| Nothing | 9 |

| New learning method | 3 |

| Better online interactions | 3 |

| Learning new skills | 6 |

| Convenience | 24 |

| Less distractions | 3 |

| More time to study | 20 |

| More time with family | 1 |

| Difficulties with online learning | 1 |

| Recorded lectures | 15 |

| Teacher availability | 8 |

| Flexibility | 1 |

| Don't know | 1 |

| More effective instruction | 7 |

| Open book tests | 1 |

| No final examinations | 1 |

| Teacher more accommodating | 2 |

| Better performance | 1 |

| More effective instruction | 1 |

| Less coursework | 1 |

| Grades not in GPA | 1 |

| Better time management | 5 |

| Teachers more accommodating; open book tests | 1 |

| More free time | 1 |

| More control of learning | 1 |

Table 14.

What one thing could your instructors have done to improve your experience after the transition to online instruction?.

| Categories | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Recorded lectures | 13 |

| Nothing | 1 |

| Monitor cheating | 2 |

| More effective instruction | 9 |

| Teach to the curriculum | 1 |

| Use a syllabus | 1 |

| Less coursework | 13 |

| More classroom interaction | 6 |

| N/A | 27 |

| Vary instruction | 10 |

| Good | 15 |

| Clearer explanations | 1 |

| Recorded lectures | 3 |

| Be more understanding (technology difficulties, grading, deadlines, and evaluations) | 20 |

| More revision | 1 |

| More small evaluations | 1 |

| Better communication | 10 |

| Slower tempo | 2 |

| Smaller workload; better evaluation scheme | 1 |

| Work on problems | 2 |

| Better organization | 4 |

| Better with technology | 2 |

| Better technology and support | 3 |

| More classroom interaction | 1 |

| Turn on cameras | 1 |

| Do not enforce cameras | 1 |

| Be consistent in using online resources | 1 |

| Enforce deadlines | 1 |

| Share lecture notes | 2 |

| Virtual whiteboard | 1 |

Table 15.

Is there anything else that you feel is important regarding your experience with the transition to online learning that you would like to share?.

| Categories | Frequency |

|---|---|

| N/A | 90 |

| Recorded lectures | 1 |

| More online courses | 1 |

| Include grades in R score | 6 |

| More conformity in online instruction delivery | 2 |

| No online phys ed | 1 |

| Be more understanding (deadlines, attendance, tests) | 5 |

| Good | 6 |

| Do better | 1 |

| Face to face is better | 6 |

| Better communication | 4 |

| Better technology | 3 |

| Online learning is hard | 7 |

| More effective instruction | 5 |

| Develop positive strategies | 5 |

| Smaller workload | 3 |

| Monitor cheating | 1 |

| Open book tests | 1 |

| Mandatory homework | 1 |

6. Discussion

This small survey reported on student perceptions of the transition to online learning at one college in Northeastern North America. Our results describe an overall successful transition in terms of student academic outcomes and instructional standards. However, this is far from saying that the transition was a runaway success. Students reported high levels of stress and anxiety, two thirds had difficulty concentrating in online learning, and few students were ready to continue studying online. While the outcomes could be worse, students will be happy to return to in-class instruction as lockdowns are lifted and institutions are reopened to the student population.

Our findings largely parallel the pre-pandemic literature on student perceptions of online learning. Students perceive both advantages and disadvantages to online learning (Ebner & Gegenfurtner, 2019). What our results highlight however, is the emotional and psychological toll of fully remote learning. Social connection is sorely lacking after many months of enforced social distancing and isolation. This stresses the importance of the social and affective dimension of online learning (León-Gómez, Gil-Fernández, & Calderón-Garrido, 2021). The relationship of the social and affective to student perceptions of online learning has not been explored in significant depth in the student perceptions literature. In light of the social effects of the pandemic on student life, our results stress the importance of online learning situations that create opportunities for connection and exchange (Doleck, Bazelais, & Lemay, 2017; Kaufmann & Vallade, 2020). Our findings show that educators and educationalists cannot ignore the social and affective dimensions when planning and delivering online instructions for the simple well-being of many students who suffer in isolation. Our findings also support the community of inquiry notions of social and cognitive presence in successful online learning environments (Akyol, Garrison, & Ozden, 2009).

In a recent study, Zheng, Yu, and Wu (2021) compared a blended learning situation where students interacted with their teacher over social media, and one face-to-face learning situation, finding that affective and cognitive learning are enhanced in blended learning and that the affective dimension appeared to mediate that effect though the two conditions did not significantly differ on grade point average, social presence, and academic self concept (though it significantly influenced cognitive learning). Studies persistently show that affective and cognitive presence are increased in blended learning (Akyol et al., 2009; Shaber et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2021). Zheng, Yu, and Wu's (2021) model is interesting as its shows quite starkly how affect and self-concept are tied to learning. These findings show that there are ways to transcend the isolation and create social and affective connections in online instruction.

Our present findings align with Zheng et al. (2021) as everyone's well-being was rudely tested by a year in social distancing and social isolation. The students in our study missed interacting with their peers in class and on campus. Many reported difficulty concentrating and heightened stress. And largely students reported increased workloads as the work shifted online. This contradicts the general discourse that assignments actually decreased. This disconnect can be understood from the perspective of distributed cognition and distributed learning, where the cognitive load is shared across a group of individuals. In this perspective the environment or the system provides affordances for activity. Work did not increase, as so much more of the cognitive load was redistributed on the individual and away from the group. Distributed cognition in an online or a face-to-face environment follow markedly different trajectories. Historically, it has been hard to reproduce online the flow of face-to-face classroom discourse where you can easily switch from one activity to another. Which is perhaps why the transition to online learning often took the form of a video conference call, with all the technical interruptions and the intrusions of private lives into the public sphere.

6.1. Limitations

As a cross-sectional survey study, we caution against any causal inferences. Moreover, the limited sample size recommends against generalizing findings to the larger population. At most, these findings are indicative of general tendencies. To show how our results might generalize, we highlight many points of convergence between our findings and the latest research on student perceptions of online learning. Our study could have been strengthened by the inclusion of other stakeholder perspectives and more in-depth qualitative analysis methods; however, we believe that our findings regarding student perceptions of online learning during the transition adds to the literature and helps to understand the encouraging and discouraging factors contributing to successful transitions to online learning.

6.2. Future directions

Future research should attempt to replicate our findings with other samples to compare results across populations to understand how institutional and contextual factors influence student perceptions of online learning. Researchers might employ more in-depth qualitative analysis methods to explore how instructional decisions interact with the social and affective dimensions and influence student receptibility to online learning.

Funding

No funding to report.

Compliance with ethical standards

Yes.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Akyol Z., Garrison D.R., Ozden M.Y. Development of a community of inquiry in online and blended learning contexts. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2009;1(1):1834–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J., Mahamed F., Williams K. Disparities in education: E-Learning and COVID-19, who matters? Child & Youth Services. 2020;41(3):208–210. doi: 10.1080/0145935x.2020.1834125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J., Rowan L., Singh P. Teaching and teacher education in the time of COVID-19. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education. 2020;48(3):233–236. doi: 10.1080/1359866x.2020.1752051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Azorín C. Beyond COVID-19 supernova. Is another education coming? Journal Of Professional Capital And Community. 2020;5(3/4):381–390. doi: 10.1108/jpcc-05-2020-0019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baticulon R., Sy J., Alberto N., Baron M., Mabulay R., Rizada L., et al. Barriers to online learning in the time of COVID-19: A national survey of medical students in the Philippines. Medical Science Educator. 2021;31(2):615–626. doi: 10.1007/s40670-021-01231-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazelais P., Doleck T., Lemay D.J. Investigating the predictive power of TAM: A case study of CEGEP students' intentions to use online learning technologies. Education and Information Technologies. 2018;23(1):93–111. doi: 10.1007/s10639-017-9587-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bazelais P., Lemay D.J., Doleck T. How does grit impact students' academic achievement in science? European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education. 2016;4(1):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson E., Horton J., Ozimek A., Rock D., Sharma G., TuYe H. 2020. COVID-19 and remote work: An early look at US data. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole A.W., Allen M., Anderson C., Bunton T., Cherney M.R., Draeger R., Jr., et al. Student predisposition to instructor feedback and perceptions of teaching presence predict motivation toward online courses. Online Learning. 2017;21:245–262. doi: 10.24059/olj.v21i4.966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel S. Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. PROSPECTS. 2020;49(1–2):91–96. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doleck T., Bazelais P., Lemay D.J. Examining the antecedents of facebook use via structural equation modeling: A case of CEGEP students. Knowledge Management & E-Learning. 2017;9(1):69–89. doi: 10.34105/j.kmel.2017.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donthu N., Gustafsson A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal Of Business Research. 2020;117:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner C., Gegenfurtner A. Learning and satisfaction in webinar, online, and face-to-face instruction: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Education. 2019;4 doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fauci A., Lane H., Redfield R. Covid-19 — navigating the uncharted. New England Journal Of Medicine. 2020;382(13):1268–1269. doi: 10.1056/nejme2002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendler R.J., Ruff C., Shrikhandle M. No significant differences – unless you are a jumper. Online Learning. 2018;22:39–60. doi: 10.24059/olj.v22i1.887. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flack C.B., Walker L., Bickerstaff A., Margetts C. Pivot Professional Learning; Melbourne, Australia: 2020. Socioeconomic disparities in Australian schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- García-Peñalvo F.J., Corell A., Abella-García V., Grande-de-Prado M. Radical solutions for education in a crisis context. Springer; Singapore: 2021. Recommendations for mandatory online assessment in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic; pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- García-Peñalvo F.J., Corell A., Rivero-Ortega R., Rodríguez-Conde M.J., Rodríguez-García N. Information technology trends for a global and interdisciplinary research community. IGI Global; 2021. Impact of the COVID-19 on higher education: An experience-based approach; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Rey P., Barbera E., Fernández-Navarro F. Student voices on the roles of instructors in asynchronous learning environments in the 21st century. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 2017;18(2) doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v18i2.2891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez T., de la Rubia M., Hincz K., Comas-Lopez M., Subirats L., Fort S., et al. Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students' performance in higher education. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase K., Cosco T., Kervin L., Riadi I., O'Connell M. Older adults' experiences of technology use for socialization during the COVID-19 pandemic: A regionally representative cross-sectional survey (preprint) JMIR Aging. 2021 doi: 10.2196/28010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Pradas S., Hernández-García Á., Chaparro-Peláez J., Prieto J. Emergency remote teaching and students' academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Computers In Human Behavior. 2021;119:106713. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman H. A review of predictive factors of student success in and satisfaction with online learning. Research In Learning Technology. 2015;23 doi: 10.3402/rlt.v23.26507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann R., Vallade J. Exploring connections in the online learning environment: Student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness. Interactive Learning Environments. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1749670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koohang A., Paliszkiewicz J., Klein D., Nord J.H. The importance of active learning elements in the design of online courses. Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management. 2016;4:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A., Kramer K. The potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2020;119:103442. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurucay M., Inan F.A. Examining the effects of learner-learner interactions on satisfaction and learning in an online undergraduate course. Computers & Education. 2017;115:20–37. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemay D.J., Doleck T. Online learning communities in the COVID-19 pandemic: Social learning network analysis of twitter during the shutdown. International Journal of Learning Analytics and Artificial Intelligence for Education. 2020;2(1):85–100. doi: 10.3991/ijai.v2i1.15427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemay D.J., Doleck T., Bazelais P. Transition to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interactive Learning Environments. 2021 doi: 10.1080/10494820.2021.1871633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- León-Gómez A., Gil-Fernández R., Calderón-Garrido D. Influence of COVID on the educational use of social media by students of teaching degrees. Education In The Knowledge Society (EKS) 2021;22 doi: 10.14201/eks.23623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marinoni G., Land H., Jensen T. The impact of Covid-19 on higher education around the world. IAU Global Survey Report. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Motz B., Quick J., Wernert J., Miles T., Pelaprat E., Jaggars S., et al. Mega-study of COVID-19 impact in higher education. 2020. https://osf.io/n7k69/ May 4.

- Nora A., Snyder B.P. Technology and higher education: The impact of E-learning approaches on student academic achievement, perceptions and persistence. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice. 2008;10(1):3–19. doi: 10.2190/CS.10.1.b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel S., Chhetri R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education For The Future. 2021;8(1):133–141. doi: 10.1177/2347631120983481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaber P., Wilcox K., Whiteside A., Marsh L., Brooks D. Designing learning environments to foster affective learning: Comparison of classroom to blended learning. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. 2010;4(2) doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2010.040212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schleicher A. The impact of covid-19 on education insights from education at a glance 2020. 2020. https://www.oecd.org/education/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-education-insights-education-at-a-glance-2020.pdf Retrieved from oecd. org website.

- Song L., Singleton E.S., Hill J.R., Koh M.H. Improving online learning: Student perceptions of useful and challenging characteristics. The Internet and Higher Education. 2004;7(1):59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2003.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stambough J., Curtin B., Gililland J., Guild G., Kain M., Karas V., et al. The past, present, and future of orthopedic education: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal Of Arthroplasty. 2020;35(7):S60–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Chen P., Law K., Wu C., Lau Y., Guan J., et al. Comparative analysis of Student's live online learning readiness during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in the higher education sector. Computers & Education. 2021;168:104211. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velavan T., Meyer C. The COVID‐19 epidemic. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2020;25(3):278–280. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W., Yu F., Wu Y.J. Social media on blended learning: The effect of rapport and motivation. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2021.1909140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]