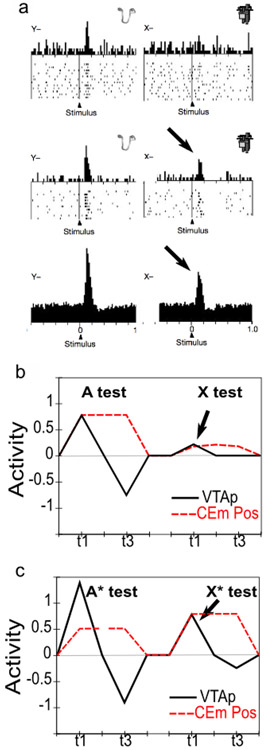

Figure 13:

Simulation 3a: Blocking. (a) Empirical results adapted from Waelti et al. (2001), Figure 2c-e with permission from Springer Nature: Nature, copyright 2001, showing substantial, but incomplete, blocking of acquired dopamine bursting for a second CS (X−) in a blocking paradigm (arrows) as compared to a second CS (Y−) compounded with a different CS not previously paired with reward. Most cells showed no response to the blocked stimulus (X−). (top) sample cell showing no response to X− but robust response to Y− control; (middle) a minority of cells showed some response, or a bi-phasic response to X−; (bottom) population histogram showing a significantly larger response to X− versus Y− control (b) Simulation results showing similarly incomplete blocking produced by the PVLV model (arrow; X test). ‘A test’ refers to presentation of the original blocking stimulus alone – it continues to show a robust dopamine response. (c) Simulation results for identity change unblocking. Test results are shown for each CS presented separately – follows training with a compounded CS2 (A*X*) when a different-but-equal-magnitude US is substituted during the blocking training phase. Note robust dopamine signal in response to the would-be blocked CS2 [compare X* test with X test in (b)]. Presentation of the original blocking stimulus alone (A* test) shows that it now drives an even stronger dopamine signal due to additional weight strengthening as a result of the unblocking effect.