Main Text

In the current issue of The Innovation, Zhao and colleagues published results of a trend analysis on hospital admission rates for all diseases in Brazil over the periods of 2000–2015. The authors identified that both hospital admission rates and length of hospital stay (LOS) have decreased largely since 2000. However, the decrease in disease burdens was accompanied by increasing health care costs. In addition, as expected, the authors discovered that the vulnerable population, infants and the elderly, had the highest rates of hospital admissions. Surprisingly, injury and poisoning became a primary cause of hospital admissions for men aged 10–49 years. Finally, regional disparity was reported; Southern Brazil had greater disease burdens. In a recent publication in Circulation, Zou and colleagues discovered that Brazil had the greatest reduction in cardiovascular disease mortality among all BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) countries, five emerging economies habituating half of the world population.1 Zhao and colleagues' study provided further details about Brazil's success in health care.

Brazil has a long history of developing a national health care system known as the Unified Health System since 1988. The current system was based on several remarkable reforms implemented in the 1990s. In 1996, Brazil introduced the results-based financing mechanism, which transferred the responsibility of administration from federal to municipal governments. Such regionalization motivated participation of local governments and government agencies to improve the efficiency and accountability of health sectors.

Another extraordinary reform was the creation of the Community Health Workers program as a component of the Family Health Strategy in 1994, aiming to provide family-based, integrated primary care services. Primary prevention, such as blood pressure and lipids screening, reduces risks for major chronic diseases and subsequently avoids hospitalizations and has played an important role in maintaining population health. Attempts to promote primary care services for all residents will increase costs for the health care system; however, such increase in costs will be offset by the decrease in hospitalizations and better health status in the long run.

The noteworthy reforms together have created a health care system that helps improve health for all residents in Brazil. As a result, life expectancy at birth increased from 66.3 years in 2000 to 72.1 years in 2017 for both genders, and infant mortality rates decreased from 30.4 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2000 to 13.2 deaths in 2017 in Brazil.2 However, compared with other BRICS countries, which also improved both life expectancy and infant mortality,2 Brazil showed a dramatic increase in health expenditure (% of gross domestic Product) from 6.6% in 2000 to 11.8% in 2016 while that in other BRICS countries remained at about 4%–8% respectively over these years.3 This may be partially due to greater coverage of the primary care and/or the updated Brazilian People's Pharmacy program in 2011. The program aims to mitigate the financial burdens by providing free or low-cost prescription medications for patients with chronic diseases. As pointed out by Zhao and colleagues, the medication subsidy program contributed to the improvement of disease burdens and the declines in hospital admission rates. On the other hand, the rapid and continuous increase in health expenditure will make the system financially unsustainable, especially as Brazil is also facing aging problems like many other countries in the world. Future studies should investigate the factors that have driven the increase in health expenditure in an effort to make the system more sustainable.

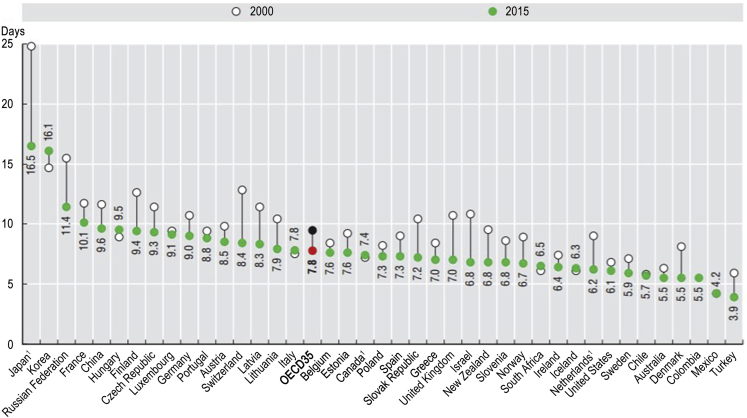

The average LOS in hospitals reflects the efficiency of a health care system.4 With all else the same, a shorter average LOS represents a cost reduction in hospital admissions by shifting care from inpatient services to less expensive post-discharge services or by avoiding unnecessary inpatient stays through utilizing adequate primary care services. Compared with countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and other BRICS countries (no information for India), Brazil, with an average LOS of 5 days estimated by Zhao and colleagues, was in the highest efficient tier. The LOS was almost 3 days below the average LOS (7.8 days) among 35 OECD countries in 2015 (Figure 1). Nonetheless, quality of care should also be considered with such a short LOS. There have been a number of studies on the impact of LOS on post-discharge mortalities for US patients, but the results varied with disease type. For instance, some studies found that LOS was negatively associated with mortality rate for some cardiovascular diseases,5, 6, 7 while others demonstrated that longer LOS in hospitals was associated with an increase in all-cause mortality.8,9 Brazil, which had lower LOS than the US (6.1 days in 2015), may also face debates over post-discharge health outcomes. Future studies are warranted to comprehensively evaluate the disease-specific post-discharge outcomes for inpatient services in Brazil.

Figure 1.

Average Length of Stay in OECD and Five Other Countries, 2000 and 2015 (Or Nearest Year)

Source: OECD Health Statistics (2017).

Overall, the Unified Health System in Brazil is a good model for promoting primary care services considering the long-term development of the health care system. Other BRICS countries may learn from the health care reforms in Brazil to develop and improve their own health care systems. However, the surging increase in health expenditure in Brazil should also be addressed. A major proportion of the total health expenditure in Brazil has been contributed by domestic private health expenditure, which was as high as 74% in 2000, decreased to 55% in 2009, and increased to 67% in 2016.10 While the study by Zhao and colleagues only explored medical records from the public health sectors, the efficiency and health expenditure considering the private sectors in Brazil should be evaluated in future studies.

References

- 1.Zou Z., Cini K., Dong B., Ma Y., Ma J., Burgner D.P., Patton G.C. Time trends in cardiovascular disease mortality across the BRICS: an age-period-cohort analysis of key nations with emerging economies using the global burden of disease study 2017. Circulation. 2020;141:790–799. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.OECD . OECD Publishing; 2019. Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The World Bank . World Bank; 2000-2016. Current Health Expenditure (% of GDP)-Brazil, Russian Federation, India, China, South Africa.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS?end=2016&locations=BR-RU-IN-CN-ZA&name_desc=false&start=2000&view=char [Google Scholar]

- 4.OECD . OECD Publishing; 2017. Average length of stay in hospitals. Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartel A.P., Chan C.W., Kim S.-H. Should hospitals keep their patients longer? The role of inpatient care in reducing postdischarge mortality. Manag. Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2019.3325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bueno H., Ross J.S., Wang Y., Chen J., Vidán M.T., Normand S.L., Curtis J.P., Drye E.E., Lichtman J.H., Keenan P.S., et al. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993-2006. JAMA. 2010;303:2141–2147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aujesky D., Stone R.A., Kim S., Crick E.J., Fine M.J. Length of hospital stay and postdischarge mortality in patients with pulmonary embolism: a statewide perspective. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008;168:706–712. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams T.A., Ho K.M., Dobb G.J., Finn J.C., Knuiman M., Webb S.A., Royal Perth Hospital ICU Data Linkage Group Effect of length of stay in intensive care unit on hospital and long-term mortality of critically ill adult patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 2010;104:459–464. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds K., Butler M.G., Kimes T.M., Rosales A.G., Chan W., Nichols G.A. Relation of acute heart failure hospital length of stay to subsequent readmission and all-cause mortality. Am. J. Cardiol. 2015;116:400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domestic private health expenditure (% of current health expenditure) - brazil. 2000-2016.