Abstract

Pre-operative exercise therapy improves outcomes for many patients who undergo surgery. Despite the well-known effects on tolerance to systemic perturbation, the mechanisms by which pre-operative exercise protects the operated organ from inflammatory injury are unclear. Here, we show that 4-week aerobic pre-operative exercise significantly attenuates liver injury and inflammation from ischemia and reperfusion in mice. Remarkably, these beneficial effects last for seven more days after completing pre-operative exercise. We find that exercise specifically drives Kupffer cells (KCs) toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype with trained immunity via metabolic reprogramming. Mechanistically, exercise-induced HMGB1 release enhances the itaconate metabolism in the TCA cycle that impacts the KCs in an Nrf2-dependent manner. Therefore, these metabolites and cellular/molecular targets can be investigated as potential exercise-mimicking pharmaceutical candidates to protect against liver injury during surgery.

Introduction

Major surgeries for malignancies, inflammation, joint replacements, cardiac, lung, and abdominal diseases result in surgery-induced stress in patients1,2. The substantial acute systemic perturbation and local injury induced by surgical stress not only worsens the patient’s post-operative outcomes and recovery period, but also accelerates tumorigenesis through immunological and/or metabolic dysregulation3,4. During major surgical procedures of the liver (e.g. resection or transplantation), patients experience substantial pathophysiological changes. The resultant hepatic inflammatory injury can lead to significant postoperative morbidity, mortality, and costs, especially in patients with a background of preexisting liver diseases with reduced liver function5,6. For example, the inflow-occlusion technique of hepatic pedicle clamping is widely used to control intraoperative hemorrhage but inevitably induces hepatic ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) injury7 and complications. As such, multiple therapeutic interventions have been developed for hepatic I/R injury8,9. However, current strategies have shown only minimal efficacy in either preventing the occurrence of hepatic I/R injury or significantly reversing its effects9–11. More efficient and reliable therapeutic approaches against I/R injury are warranted for patients undergoing liver surgeries.

Exercise has been well demonstrated to maintain and restore homeostasis at the organismal, tissue, cellular, and molecular levels to prevent or inhibit numerous disease conditions12. It has been documented that exercise therapy is an effective pre-operative therapy providing multiple beneficial effects on patients’ physical fitness before surgery, the recovery period, and the length of hospital admission13–15. One major mechanism underlying the advantageous effect of exercise therapy is based on systemically improving patients’ pre-operative cardiovascular reserve capacity, which is essential for whole-body tolerance to systemic perturbation16–18. However, understanding of the mechanisms by which pre-operative exercise therapy protects local organs, such as the liver, from inflammatory injury are far from complete. The absence of mechanistic studies for pre-operative exercise therapy with large-scale, well-designed clinical trials hampers the widespread application of such a highly useful, easily employable, non-pharmacological therapeutic strategy. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of pre-operative exercise therapy would help unlock its full potential and, more importantly, benefit exercise-intolerant patients with the availability of potential pharmacological pre-operative exercise-mimics.

Exercise training has been shown to initiate metabolic reprogramming in many cell types19. Most recently, exercise training was shown to improve cognition of aged animals by ameliorating increased glycolysis in aged microglia, the residential macrophage in the central nervous system20. The metabolic profile of immune cells is critical for their inflammatory phenotype. For instance, pro-inflammatory macrophages are known to gain energy through aerobic glycolysis, whereas anti-inflammatory macrophages via oxidative phosphorylation21. Therefore, it is conceivable that pre-operative exercise therapy alters the immune environment in the liver during surgery via the metabolic reprogramming of immune cells. However, how pre-operative exercise therapy alters the hepatic immune environment and its underlying mechanisms remains unknown.

Trained immunity is a de facto immune memory of the innate immune system. The innate immune cells undergo a long-term functional reprogramming with a first challenge, return to a non-activated stage, and if met with a second challenge, robustly reactivated with displaying highly adaptive characteristics22. Innate immune cells, such as macrophages23, can be trained to acquire adaptive immune functions. Metabolic reprogramming in response to an initial stimulation is a major mechanism of inducing trained immunity22. Certain metabolites, such as mevalonate24, succinate, and itaconate25 have been shown to induce innate immune memory via modulation. However, whether pre-operative exercise therapy offers protection against hepatic injury through training of innate immune cells to acquire immune memory remains unknown.

In this study, we used a clinically relevant mouse model of hepatic I/R injury and examined the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of pre-operative exercise therapy on hepatic injury after I/R. We found that pre-operative exercise therapy protected the liver from inflammatory injury after hepatic I/R as expected. Surprisingly, pre-operative exercise therapy-induced beneficial effects remained up to seven days after completing pre-operative exercise therapy. We further investigated this finding by using single-cell technologies and discovered that exercise had an impact on the hepatic immune microenvironment. Exercise resulted in trained Kupffer cells (KCs) favoring an anti-inflammatory phenotype via metabolic reprogramming. Mechanistically, exercise-induced HMGB1 release increased the level of itaconate, an anti-inflammatory metabolite in the TCA cycle that trained the KCs towards anti-inflammatory phenotype via Nrf2. Thus, our studies uncover the mechanisms of a previously unknown role of pre-operative exercise therapy in training innate immunity via metabolic reprogramming in KCs to ultimately improves inflammatory injury after hepatic I/R.

Results

Exercise Attenuates Hepatic I/R Injury by Altering the Immune Microenvironment.

To understand how pre-operative exercise therapy improves the liver that have been operated at the cellular and molecular levels, we used hepatic I/R injury in a mouse model to study the effects of pre-operative exercise therapy on invasive surgical procedures. First, we determined the optimal length of pre-operative exercise therapy needed to protect the liver from I/R injury by providing exercise therapy to eight-week-old C57BL/6 male mice via a motorized treadmill exercise schedule or control sedentary treatment for up to 16 weeks, and then subjecting the mice to hepatic I/R stress (Fig. 1a). Mice subjected to both 1-day-exercisex and 1-day-sedentary treatment showed equal degrees of liver injury, as indicated by serum alanine aminotransferase (sALT), serum aspartate transaminase (sAST) levels as well as histological evaluation (necrotic areas and Suzuki scores) (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1a). The liver injury in mice after I/R insult decreased gradually with the increase of exercise length, and the injury was at the lowest level after 4-week pre-operative exercise when compared with similar sedentary control mice (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1a–c). Extended pre-operative exercise periods beyond 4 weeks up to 16 weeks offered no further hepatic protection (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1a, d). Next, we measured the levels of circulating anti-inflammatory cytokines. Intriguingly, we found that circulating levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10 and IL-1Ra) were significantly higher in the 4-week exercise mice compared with the 4-week sedentary control mice not only after I/R but also before I/R at baseline (Fig. 1c). Concurrently, circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were significantly lower in the 4-week exercise mice compared with their 4-week sedentary control both at baseline and after I/R (Fig.1c and Extended Data Fig. 1e, f). These data indicate that 4-week is the optimal length of pre-operative exercise needed to protect mice from hepatic I/R injury. Moreover, for human patients, about four weeks is also the average time interval between diagnosis and surgery in clinical practice26,27. Therefore, in this study, we set 4-week pre-operative exercise as the standard for further examining its beneficial effects. We then investigated how long the pre-operative exercise-induced beneficial effects last using 4-week exercise or sedentary -mice, which were allowed to rest for 0, 3, 5, or 7 days before I/R (Fig. 1d). Surprisingly, the levels of liver injury were significantly lower in exercise-mice than sedentary-mice even after 7-days of rest (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 1g), indicating the beneficial effects on hepatic injury can be expected at least up to seven days after completing pre-operative exercise regimen.

Fig. 1 |. Exercise Attenuates Hepatic I/R Injury by Altering the Immune Microenvironment.

a, Experiment outline. C57BL/6 male mice received sedentary or pre-operative exercise treatment for 1 day, or 1 to 16 weeks, were subjected to hepatic ischemia/reperfusion (I/R). b, Liver damage was measured by serum ALT level (P=0.8498, P=0.2905, P=0.0606, P=0.0541, P<0.0001, P<0.0001, P<0.0001, P<0.0001 between exercise and sedentary group from 1day to 16 weeks respectively) and liver histological evaluation (necrotic areas) (P=0.7817, P=0.7957, P=0.3412, P=0.0518, P=0.0003, P=0.001, P=0.0001, P=0.0003 between exercise and sedentary group from 1day to 16 weeks respectively) from exercise or sedentary mice with (1 day, or 1 to 16 weeks) which subjected to hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). c, Serum IL-1Ra (P=0.0298 in sham group, P=0.0015 in I/R group), IL-10 (P=0.0207 in sham group, P=0.0018 in I/R group), IL-1β (P=0.0125 in sham group, P=0.0004 in I/R group), IL-6 (P=0.0166 in sham group, P=0.0115 in I/R group) and TNF-α (P=0.003 in sham group, P=0.006 in I/R group) concentrations were measured by ELISA from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) at baseline (SHAM group) and subjected to hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). d, Experiment outline. C57BL/6 male exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) and resting for 0, 3, 5, or 7 days before hepatic I/R. e, Liver damage was measured by serum ALT level (P<0.0001 between sedentary and all exercise group, p=0.3259 between 0 days and 3 days group, P=0.995 between 0 day and 5 days group, P=0.9750 between 0 day and 7 days group, P=0.2701 between 3 days and 5 days group, P=0.2765 between 3 days and 7 days group, P=0.5726 between 5 days and 7 days group) and liver histological evaluation (necrotic areas) (P=0.0006 between sedentary and 0 day group, P=0.0003 between sedentary and 3 days group, P=0.0001 between sedentary and 5 days group, P=0.0001 between sedentary and 7 days group, P=0.8815 between 0 days and 3 days group, P=0.5466 between 0 day and 5 days group, P=0.2979 between 0 day and 7 days group, P=0.6323 between 3 days and 5 days group, P=0.2765 between 3 days and 7 days group, P=0.8181 between 5 days and 7 days group) from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) and resting for 0, 3, 5, or 7 days before hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=11 in sedentary group, n=7 in 0D after Exercise group, n=15 in 3D after Exercise group, n=9 in 5D after Exercise group, n=7 in 7D after Exercise group). f, Percentage of Kupffer cells (KCs) and monocytes. g, Numbers of Kupffer cells (P<0.0001 in sham group, P<0.0001 in I/R group), monocytes (P=0.0056 in sham group, P=0.004 in I/R group), natural killer (NK) cells (P=0.0013 in sham group, P=0.002 in I/R group), and neutrophils (P=0.0137 in sham group, P=0.0001 in I/R group) (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). Graphs show the mean ± SD (b, c, e and g). Circles, triangles and squares represent individual mice. ANOVA with adjustment for multiple comparisons (b and e). Unpaired two-sample Student’s t test (c and g). ***p < 0.001; NS: not significant. All the statistical test used in this figure was two-sided and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Hepatic I/R can drive robust inflammatory responses in the hepatic immune microenvironment, leading to severe postoperative organ damage28. To determine whether pre-operative exercise therapy alters the landscape of the hepatic immune microenvironment, we first used mass cytometry (CyTOF) to resolve the hepatic immune profile29. Kupffer cells (KCs), monocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and NKT cells were identified in the CD45+ hepatic immune cell population before and after I/R from both exercise and sedentary mice (Extended Data Fig. 2a). Compared to the mice with sedentary treatment, the exercise mice had substantially higher percentages of KCs and lower percentages of infiltrating monocytes and neutrophils before and after liver I/R (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Using flow cytometry, we confirmed that both the percentages and numbers of KCs and NK cells were substantially higher in the liver of exercise mice than sedentary mice (Fig. 1f, g, and Extended Data Fig. 2c, d). Furthermore, the percentages and numbers of infiltrating monocytes and neutrophils in the liver increased after I/R compared with sham, but substantially decreased if the mice received pre-operative exercise therapy but not sedentary treatment (Fig. 1f, g, Extended Data Fig. 2e). These data demonstrate that pre-operative exercise therapy alters the hepatic immune microenvironment in a specific way at both before and after I/R and may be the underlying basis for pre-operative exercise-mediated post-surgical benefits.

Exercise Shifts KCs towards an Anti-Inflammatory Transcriptomic Profile.

To gain an in-depth understanding of how pre-operative exercise therapyx modulates hepatic immune micro-environment at the cellular and molecular levels, we employed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on hepatic leukocytes (CD45+) isolated from 4-week exercise mice and sedentary controls before liver I/R30 (Extended Data Fig. 3a). In total, 15,332 cells were resolved and clustered into 18 discrete populations (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 3b). As shown in the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) of single CD45+ cells, ten cell lineages--KCs, DCs, monocytes, neutrophils, B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, NK cells, NKT cells, and CD45- cells--were identified and annotated according to the transcriptomic profile of feature genes expression31,32 (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 3c). Surprisingly, 4-week-pre-operative exercise therapy led to a significant transcriptomic shift only in the Cluster 0 and Cluster 2 KCs but not in other immune cell types. Based on the percentage of cells from each group and the ratio of observed to expected cell numbers (Ro/e) in each cluster, we found that Cluster 0 was one unique subpopulation of KCs mainly derived from exercise mice and Cluster 2 KCs was mainly from sedentary mice (Figures 2c and Extended Data Fig. 4a–d). By analyzing the differentially expressed genes (DEG) between exercise-associated KCs (Cluster 0) and sedentary-associated KCs (Cluster 2), we found that there were only two upregulated DEG--Rsrp1 and Paqr9; avg_logFC > 0.2, P_val_adj > 0.05--in Cluster 0 compared to Cluster 2 (Fig. 2d). However, there were 62 down-regulated DEG--Tnfaip3, Ccl2, Ccl3, Ccl4, Ccl7, Cxcl2, Cxcl10, Vcam1, etc.--in Exercise-KCs compared to Sedentary-KCs (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Fig. 4e). Gene ontology (GO) analysis on down-regulated DEG revealed that genes associated with cytokine-mediated signaling pathways, responses to chemokines, IL-1β production, and leukocyte differentiation were down-regulated in Exercise-KCs compared with Sedentary-KCs (Fig. 2e). These data strongly suggest that pre-operative exercise therapy induces changes in the overall transcriptional profile in KCs and shifts it as a strong anti-inflammatory armamentarium.

Fig. 2 |. Exercise Shifts KCs towards an Anti-Inflammatory Transcriptomic Profile.

a, Based on the transcriptomic profile, 15,332 cells were clustered into 18 discrete cell populations in Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). b, UMAP of single CD45+ cells, ten cell lineages, Kupffer cells (KCs), monocytes, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells and CD45- cells were identified and annotated according to the transcriptomic profile of feature genes expression. c, Group distribution of Kupffer cells in cluster 0 (Ex-associated KCs) and 2 (sedentary-associated KCs) (n=2 mice per group). d, Heatmap of differentially expressed genes (DEG) between Cluster 0 (Ex-associated KCs) and Cluster 2 (Sed-associated KCs). Red=high relative expression, Blue=low relative expression. e, Gene Ontology (GO) analysis on down-regulated DEG enriched in signaling pathways associated with cytokine-mediated signaling pathways, responses to chemokines, IL-1β production, and leukocyte differentiation in Cluster 0 compared with Cluster 2.

Exercise Drives KCs to Be an Anti-Inflammatory Phenotype.

As the above results indicated that pre-operative exercise therapy selectively induced an anti-inflammatory transcriptomic profile in KCs, we postulated that this was the underlying mechanism of pre-operative exercise therapy mediated beneficial effects on the liver after I/R. To test the hypothesis, we first examined if the KCs had acquired an anti-inflammatory phenotype after pre-operative exercise by studying the levels of released cytokines from KCs obtained from exercise mice (Ex-KCs) and control sedentary mice (Sed-KCs) (Extended Data Fig. 5a). As expected, Ex-KCs gradually increased the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-1Ra and IL-10 and reduced proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in a time-dependent manner. These gradual changes reached significance only after 4 weeks of pre-operative exercise compared with Sed-KCs (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3 |. Exercise Drives KCs to Be an Anti-Inflammatory Phenotype.

a, IL-1Ra (P=0.9184, P=0.1420, P=0.0606, P=0.0057, P=0.0004 between exercise and sedentary group from 1day to 4 weeks), IL-10 (P=0.5441, P=0.0585, P=0.0535, P=0.0516, P=0.0095 between exercise and sedentary group from 1day to 4 weeks), IL-1β (P=0.6095, P=0.0797, P=0.1936, P=0.0639, P=0.0053 between exercise and sedentary group from 1day to 4 weeks), IL-6 (P=0.9485, P=0.0797, P=0.1936, P=0.0643, P=0.0015 between exercise and sedentary group from 1day to 4 weeks), and TNF-α (P=03148, P=0.2218, P=0.0720, P=0.0547, P=0.0053 between sedentary and exercise group from 1day to 4 weeks), concentrations in the culture medium of Kupffer cells (KCs) from exercise or sedentary mice (1 day or 1 to 4 weeks) were measured by ELISA (n=6 mice per group). b, Liver damage was measured by serum ALT level (P=0.0012 in saline group, P=0.6458 in GdCl3 group) and liver histological evaluation (necrotic areas) (P=0.0025 in saline group, P=0.5115 in GdCl3 group) from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) injected with gadolinium chloride (GdCl3) (25 mg/kg) or saline solution intraperitoneally 48 hours before hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). c, Serum IL-1Ra (P=0.0001 in saline group, P=0.5625 in GdCl3 group), IL-10 (P<0.0001 in saline group, P=0.7537 in GdCl3 group), IL-1β (P=0.0003 in saline group, P=0.3116 in GdCl3 group), IL-6 (P=0.0003 in saline group, P=0.2129 in GdCl3 group) and TNF-α (P=0.0019 in saline group, P=0.5262 in GdCl3 group) concentrations were measured by ELISA from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) injected with gadolinium chloride (GdCl3) (25 mg/kg) or saline solution intraperitoneally 48 hours before hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). d, Adoptive transfer of KCs isolated from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) into KCs-depleted mice with GdCl3 (25 mg/kg). Liver damage was measured by serum ALT level (P=0.0009 in sedentary recipient group, P=0.0027 in exercise recipient group) and liver histological evaluation (necrotic areas) (P=0.0065 in sedentary recipient group, P=0.0053 in in exercise recipient group) among mice from these four groups subjected to hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). e, Adoptive transfer of KCs isolated from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) into KCs-depleted mice with GdCl3 (25 mg/kg). Serum IL-1Ra (P=0.0009 in sedentary recipient group, P<0.0001 in exercise recipient group), IL-10 (P<0.0001 in sedentary recipient group, P=0.0023 in exercise recipient group), IL-1β (P<0.0001 in sedentary recipient group, P<0.0001 in exercise recipient group), IL-6 (P<0.0001 in sedentary recipient group, P=0.0004 in exercise recipient group) and TNF-α (P<0.0001in sedentary recipient group, P<0.0001 in exercise recipient group) concentrations were measured by ELISA among mice from these four groups subjected to hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). Graphs show the mean ± SD (a-e). Circles and triangles represent individual mice. ANOVA with adjustment for multiple comparisons for (a). Unpaired two-sample Student’s t test for (b-e). All the statistical test used in this figure was two-sided and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Next, we tested whether KCs are required for pre-operative exercise-induced protective effects on the liver after I/R by depleting KCs in exercise and sedentary mice. We administered gadolinium chloride (GdCl3)33 intraperitoneally 48 hours before liver I/R and successfully depleted 95% of KCs in mice (Extended Data Fig. 5b, c). Consistent with previous findings34, depletion of KC substantially reduced liver injury and inflammation in the sedentary mice after I/R as indicated by lower levels of sALT, sAST, liver necrotic area, Suzuki score, and pro-inflammation cytokines production (Fig. 3b, c and Extended Data Fig. 5d). These data suggested that KCs are the main players that cause liver injury in response to hepatic I/R. Strikingly, depletion of KCs in exercise mice also abrogated the protective effects of pre-operative exercise on I/R, indicating that KCs are also required for the pre-operative exercise induced protective effects (Fig. 3b, c). Furthermore, adoptively transfer of Ex-KCs (5×106 per mouse)35 into KC-depleted mice at 2 hours before liver I/R36 (Extended Data Fig. 5e) substantially decreased organ damage and inflammation after I/R compared with adoptive transfer of the Sed-KCs (Fig. 3d, e and Extended Data Fig. 5f). Together, these data indicate that pre-operative exercise protects the liver from I/R injury via driving KCs towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype.

Exercise Promotes Metabolic Reprogramming in KCs.

The inflammatory phenotype of macrophages is known to be altered by metabolic reprogramming37,38. Exercise training has been shown to modulate glycolysis in aged microglia20. To determine if pre-operative exercise induces metabolic reprogramming in KCs, we first assessed the glycolytic flux of isolated Ex-KCs and Sed-KCs. We used the Seahorse XF analyzer to measure oxygen consumption (OCR) and their extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of KCs. Interestingly, we found that mitochondrial respiration rate and ATP production were significantly higher in Ex-KCs mice than Sed-KCs at baseline (Fig. 4a). When subjected to hypoxia, which mimics I/R injury in vitro39, Ex-KCs showed an escalated rate of mitochondrial respiration and ATP production compared with Sed-KCs (Fig. 4a). Conversely, ECAR was significantly lower in Ex-KCs compared with Sed-KCs at both baseline and under hypoxia (Fig. 4b). The OCR/ECAR ratio is substantially higher in Ex-KCs than Sed-KCs at both baseline and under hypoxia (Fig. 4c). These data provide strong clues that pre-operative exercise shifts the metabolic profile of KCs from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS).

Fig. 4 ||. Exercise Promotes Metabolic Reprogramming in KCs.

a, The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) of Kupffer cells (KCs) from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) with or without the challenge of hypoxia (1% O2) for 24 hours, followed by re-oxygenation under normoxic conditions (21% O2) for 10 hours were measured using mito-stress kit through a Seahorse XFe24 extracellular flux analyzer. Left, OCR of KCs after treatment with oligomycin for 6–8 hours in vitro. Right, basal, ATP and maximal respiration rates for control (P<0.0001 in basal group, P=0.0098 in ATP group, P=0.0110 in maximal group) and hypoxia (P=0.0007 in basal group, P=0.0006 in ATP group, P<0.0001 in maximal group) condition (n=5 mice per group). b, The extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of KCs from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) with or without the challenge of hypoxia (1% O2) for 24 hours, followed by re-oxygenation under normoxic conditions (21% O2) for 10 hours were measured using mito-stress kit through a Seahorse XFe24 extracellular flux analyzer. Left, ECAR of KCs after treatment with oligomycin for 6–8 hours in vitro. Right, analysis of aerobic glycolysis for each condition (P=0.0004 in control group, P=0.0006 in hypoxia group) (n=5 mice per group). c, OCR/ECAR rate of KCs from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) with or without the challenge of hypoxia (1% O2) for 24 hours, followed by re-oxygenation under normoxic conditions (21% O2) for 10 hours were measured using ATP rate kit through Seahorse XFe24 extracellular flux analyzer for control (P<0.0001 in sedentary group, P<0.0001 in exercise group) and hypoxia (P=0.0124 in sedentary group, P=0.0006 in exercise group) condition (n=5 mice per group). Total metabolite profiling in KCs from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) was determined by the metabolomics assay based on liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and assessed by principle-component analysis (d) (Each dot represents one mouse, n=5 mice per group) and pathway-enrichment analysis (e). f, Schematic view of the TCA cycle and the pathways involved in itaconate synthesis. Citrate (P=0.0112), aconitate (P=0.0387), itaconate (P=0.0103), succinate (P=0.0003), fumarate (P=0.0075), and malate levels (P=0.0112) in KCs were normalized to cell number (Each dot represents one mouse, n=5 mice per group). Graphs show the mean ± SD (a, b, c and f). ANOVA with adjustment for multiple comparisons (left parts of a and b). Unpaired two-sample Student’s t test (right parts of a and b; c and f). All the statistical test used in this figure was two-sided and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To gain further insights into how pre-operative exercise metabolically reprograms KCs, we performed non-targeted steady-state metabolomics profiling of the Ex-KCs and Sed-KCs using a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)-based metabolomics assay40. We found that the intracellular metabolite profile of KCs from exercise mice was markedly altered when compared to that of KCs from sedentary mice, as indicated by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (Fig. 4d). Gene expression and pathway-enrichment analyses showed sugar-related metabolisms, such as pentose, glycolysis and pyruvate, and tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA cycle) pathways were enriched in Ex-KCs compared to Sed-KCs (Fig. 4e, f and Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). When we further analyzed the levels of intermediate metabolites in TCA cycles, we found that pre-operative exercise substantially increased the itaconate metabolism (Fig. 4g). Concurrently, pre-operative exercise suppressed the downstream metabolism of succinate-fumarate metabolism, as indicated by the decreased levels of these metabolites in Ex-KCs compared with Sed-KCs (Fig. 4g). Together, these data demonstrate that pre-operative exercise metabolically reprograms the TCA cycle in KCs.

Exercise-attenuated Hepatic I/R injury is Dependent on Itaconate/IRG1.

Itaconate is a metabolic product of cis-aconitic acid decarboxylation in the TCA cycle, which is decarboxylated by aconitate decarboxylase 1 (ACOD1; CAD), also called Immune-responsive gene 1 protein (IRG1)21. Itaconate/IRG1 is crucial for driving macrophage differentiation towards M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages during oxidative and electrophilic stress responses21. Deletion of Irg1 has been shown to increase the production of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages when exposed to LPS41 and exacerbated liver I/R injury42. To test if pre-operative exercise therapy induced anti-inflammatory phenotype of KCs is dependent on itaconate/IRG1, we first determined whether the expression of IRG1 is affected by pre-operative exercise. IRG1 expression in KCs of 4-week exercise mice was substantially higher than that found in sedentary control mice (Fig. 5a, b). To test whether IRG1 is required for pre-operative exercise therapy induced protection, Irg1+/+ and Irg1−/− mice were subjected to 4-week exercise or sedentary treatment followed by hepatic I/R. As expected, depletion of Irg1 exacerbated liver I/R injury in both exercise and sedentary mice. Notably, the levels of liver injury and circulating inflammatory cytokines were comparable between exercise and sedentary treatment in Irg1−/− mice (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 7a–c), indicating that itaconate is critical for exercise induced protection. To study the beneficial effects of pre-operative exercise on hepatic liver I/R injury is dependent on IRG1 in KCs, we continued using the established adoptive transfer model. KCs-depleted Irg1+/+ mice were adoptively transferred with Irg1−/− or Irg1+/+ KCs from sedentary or exercise mice (Fig. 5d). Compared to Irg1+/+ KCs from Sed mice, adoptive transfer of Irg1+/+ KCs from exercise mice significantly reduced liver injury. Notably, adoptive transfer of Irg1−/− KCs from sedentary or exercise mice showed significantly increased liver I/R injury compared with adoptive transfer of Irg1+/+ KCs. Importantly, there was no significant difference in sAST and sALT levels between the adoptive transfer of Irg1−/− Kupffer cells from sedentary and exercise mice (Fig. 5e and Extended Data Fig. 7d).

Fig. 5 |. Exercise-induced HMGB1 activates the Itaconate/IRG1/Nrf2 signaling in KCs.

a-b, The Immune-responsive gene 1 (Irg1) gene (a) (Each dot represents one mouse, n=9 mice in sedentary group, P<0.0001 n=7 mice in exercise group) and protein (b) level (P=0.0002) in Kupffer cells (KCs) from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) was measured by real-time PCR and western blot (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). c, Liver damage for Irg1+/+ and Irg1−/− exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) after hepatic I/R was measured by serum ALT level (P=0.0007 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1+/+ exercise group, P=0.0475 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1−/− sedentary group, P<0.0001 between Irg1+/+ exercise and Irg1−/− sedentary group, P<0.0001 between Irg1+/+ exercise and Irg1−/− exercise group, P=0.1282 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1−/− exercise group) (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). d, Experiment outline for adoptive transfer model. e, Liver damage of KCs-depleted Irg1+/+ mice were adoptively transferred with Irg1−/− or Irg1+/+ KCs from exercise or sedentary mice after hepatic I/R were measured by serum ALT levels (P=0.0009 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1+/+ exercise group, P=0.0369 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1−/− sedentary group, P<0.0001 between Irg1+/+ exercise and Irg1−/− sedentary group, P<0.0001 between Irg1+/+ exercise and Irg1−/− exercise group, P=0.6143between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1−/− exercise group) (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). f-g, Liver damage for Irg1+/+ exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) injected vehicle (P<0.0001 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1+/+ exercise group, P=0.0019 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1−/− sedentary group, P<0.0001 between Irg1+/+ exercise and Irg1−/− exercise group, P=0.8131 between Irg1−/− sedentary and Irg1−/− exercise group) or 4-octyl itaconate (4-OI, 25 mg/kg) (P=0.0158 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1+/+ exercise group, P=0.0032 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1−/− sedentary group, P=0.0021 between Irg1+/+ exercise and Irg1−/− exercise group, P=0.0007 between Irg1−/− sedentary and Irg1−/− exercise group) (f) or itaconate (100mg/kg) (P=0.0128 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1+/+ exercise group, P=0.1237 between Irg1+/+ sedentary and Irg1−/− sedentary group, P=0.0234 between Irg1+/+ exercise and Irg1−/− exercise group, P=0.0139 between Irg1−/− sedentary and Irg1−/− exercise group) (g) 24 and 2 hours before hepatic ischemia, and at the time of reperfusion, was measured by serum ALT level (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). h, The serum HMGB1 level in mice from Sedentary versus Exercise group. i, The IRG1 protein level in Kupffer cells from Tlr4+/+ and Tlr4−/− mice with 24 hours PBS or rHMGB1 (10 μg/ml) treatment (P=0.6633, P=0.1780, P=0.0503, P=0.0528, P=0.0107 between sedentary and exercise group with the treatment from 1day to 4 weeks) (n=6 mice per group). j, The Nrf2 protein level in KCs from exercise or sedentary mice. k, Liver damage for Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− Ex or Sed mice (4 weeks) after hepatic I/R was measured by serum ALT level (P=0.0008 between Nrf2+/+ sedentary and Nrf2+/+ exercise group, P=0.0371 between Nrf2+/+ sedentary and Nrf2−/− sedentary group, P=0.0002 between Nrf2+/+ exercise and Nrf−/− exercise group, P=0.9542 between Nrf2−/− sedentary and Nrf2−/− exercise group) (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice in both Nrf2+/+ Sedentary and Exercise group, n=3 in Nrf2−/− Sedentary group, n=5 in Nrf2−/− Exercise group). l, The Nrf2 protein level in KCs from Irg1−/− or Irg1+/+ exercise and sedentary mice. For Western blotting, each lane represents a separate animal. The blots shown are representatives of three experiments with similar results. Graphs show the mean ± SD (a, b, c, e, f, g, h and k). Circles, triangles and squares represent individual mice. Unpaired two-sample Student’s t test (a and b). ANOVA with adjustment for multiple comparisons (c, e, f, g, h and k). All the statistical test used in this figure was two-sided and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To test whether treatment of exogenous itaconate or itaconate derivatives can rescue the liver from IR injury, we treated exercise or exercise mice with unmodified itaconate43 (12C-ITA, 100 mg/kg) or 4-octyl itaconate (4-OI, 25mg/kg), one of the cell-permeable itaconate derivatives44, 24 and 2 hours before hepatic ischemia, and at the time of reperfusion. Regardless Irg1−/− or Irg1+/+ mice, both itaconate and 4-OI protected the liver from I/R injury not only in sedentary mice, but also conferred further protection in exercise mice (Fig. 5g and Extended Data Fig. 7e, f). Furthermore, both of treatments reversed the adverse effect of Irg1−/− on the pre-operative exercise mice. Taken together, our data suggest that the itaconate/IRG1 metabolic pathway plays a crucial role in determining the anti-inflammatory immunophenotype of KCs, and, therefore, the beneficial effects of pre-operative exercise on hepatic I/R injury occur via regulating the itaconate metabolism.

Exercise-induced HMGB1 activates the Itaconate/IRG1/Nrf2 signaling in KCs.

Irg1 expression has been demonstrated to be increased in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated macrophages21. However, LPS, an important microbial component of gram-negative bacteria outer membranes, would not be detected locally or systemically during pre-operative exercise because it is a pathogen-free environment. High Mobility Group Box (HMGB)1 signaling through Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 (same pattern recognition receptor (PRR) as LPS on macrophages45), has been shown to be released from myocytes during exercise46. Therefore, we next tested whether pre-operative exercise induced HMGB1 promotes the IRG1 expression in KCs via TLR4. Consistent with others46, we observed that serum levels of HMGB1 were gradually elevated during pre-operative exercise and increased one-fold at 4 weeks of exercise compared with sedentary controls (Fig. 5h). Further, we obtained KCs from both Tlr4+/+ and Tlr4−/− mice and treated them with PBS or recombinant HMGB1 (rHMGB1) (10 μg/mL) for 24 hours47. Treatment of rHMGB1 increased IRG1 expression in Tlr4+/+ KCs but not in Tlr4−/− KCs, indicating that HMGB1 induces IRG1 expression via TLR4 (Fig. 5i).

4-OI has recently been identified to directly alkylate cysteine residues in KEAP1, leading to an upregulation of an anti-oxidative transcription factor, nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) in macrophages during endotoxemia44. Thus, we determined whether Nrf2 was involved in pre-operative exercise’s effect on improving organ injury and inflammation. We first observed that Nrf2 expression increased in KCs from exercise mice compared with sedentary mice KCs (Fig. 5j). To test whether Nrf2 is required for pre-operative exercise induced protection, Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice were subjected to 4-week exercise or sedentary treatment followed by hepatic I/R. As expected, deletion of Nrf2 exacerbated liver I/R injury in both exercise and sedentary mice, indicating Nrf2 is involved in the beneficial effect of pre-operative exercise on hepatic I/R injury in vivo (Fig. 5k and Extended Data Fig. 7g). To further determined whether Nrf2 is involved in IRG1 signaling during exercise, we obtained the KCs from Irg1−/− or Irg1+/+ mice with exercise or sedentary treatment. Nrf2 expression was almost abolished in Irg1−/− KCs regardless exercise or sedentary treatment (Fig. 5l), suggesting Nrf2 is involved in IRG1 signaling pathway.

Exercise Promotes an Anti-Inflammatory Trained Immunity in KCs.

Our data suggest that pre-operative exercise induced beneficial effects can be reactivated due to immune memory (Fig. 1e), and that the KCs are required for the pre-operative exercise induced beneficial effects on surgical outcomes in the liver. Taking into account that pre-operative exercise is the first stimulator and hepatic I/R the second stimulator, we hypothesized that pre-operative exercise bestowed innate immune memory/trained immunity in KCs. Although trained immunity has been studied in circulating macrophages48, it is unclear whether this immunity can be induced in resident macrophages, such as liver KCs. To answer this question, KCs obtained from normal control mice were initially treated with β-glucan for 24 hours to induce trained immunity or treated with PBS as control49. After 5-day of rest, KCs were exposed to LPS for 24 hours (Extended Data Fig. 8a). The levels of anti-inflammatory IL-1Ra and IL-10 cytokines in the media were noticeably higher, and the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were lower in β-glucan-treated KCs when compared to PBS-treated KCs (Extended Data Fig. 8b). These results imply that that the resting macrophages such as KCs are amenable to induce trained immunity.

Next, we examined whether pre-operative exercise induces trained immunity in KCs by obtaining KCs from exercise mice or Sed mice, followed by resting for 5-days, and then subjected to hypoxia (Fig. 6a) to mimic in vitro liver injury. Considering pre-operative exercise as the first challenge during the trained immunity process, we observed significantly increased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines and lower levels of proinflammatory cytokines as above in Ex-KCs when compared to Sed-KCs (Fig. 6b, c). Notably, all the cytokines levels in the media from both Ex- and Sed-KCs returned to the baseline level after 5-day resting (Fig. 6b, c). However, in response to hypoxia that served as the second challenge in the trained immunity process, the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines produced by Ex-KCs were remarkably higher than those produced by Sed-KCs (Fig. 6b). Likewise, the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by Ex-KCs was significantly lower compared with Sed-KCs after hypoxia (Fig. 6c). These results indicate that pre-operative exercise promotes anti-inflammatory trained immunity in KCs. Similar results were obtained when we exposed Ex-KCs and Sed-KCs to LPS as a classic second challenge in the trained immunity process (Extended Data Fig. 8c, d). To test if pre-operative exercise induces anti-inflammatory trained immunity in vivo, we isolated KCs from 4-week-exercise or sedentary mice after liver I/R or LPS challenge (Extended Data Fig. 8e). Consistent with Fig. 1d and 1e, we found four weeks of pre-operative exercise significantly protected the liver from LPS challenge in vivo even after giving the mice up to seven days of rest after pre-operative exercise (Extended Data Fig. 8f). As expected, even after 7-day rest, Ex-KCs produced significantly more anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-1Ra and IL-10 and less pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in response to liver I/R or LPS challenge (Fig. 6d, e and Extended Data Fig. 8g).

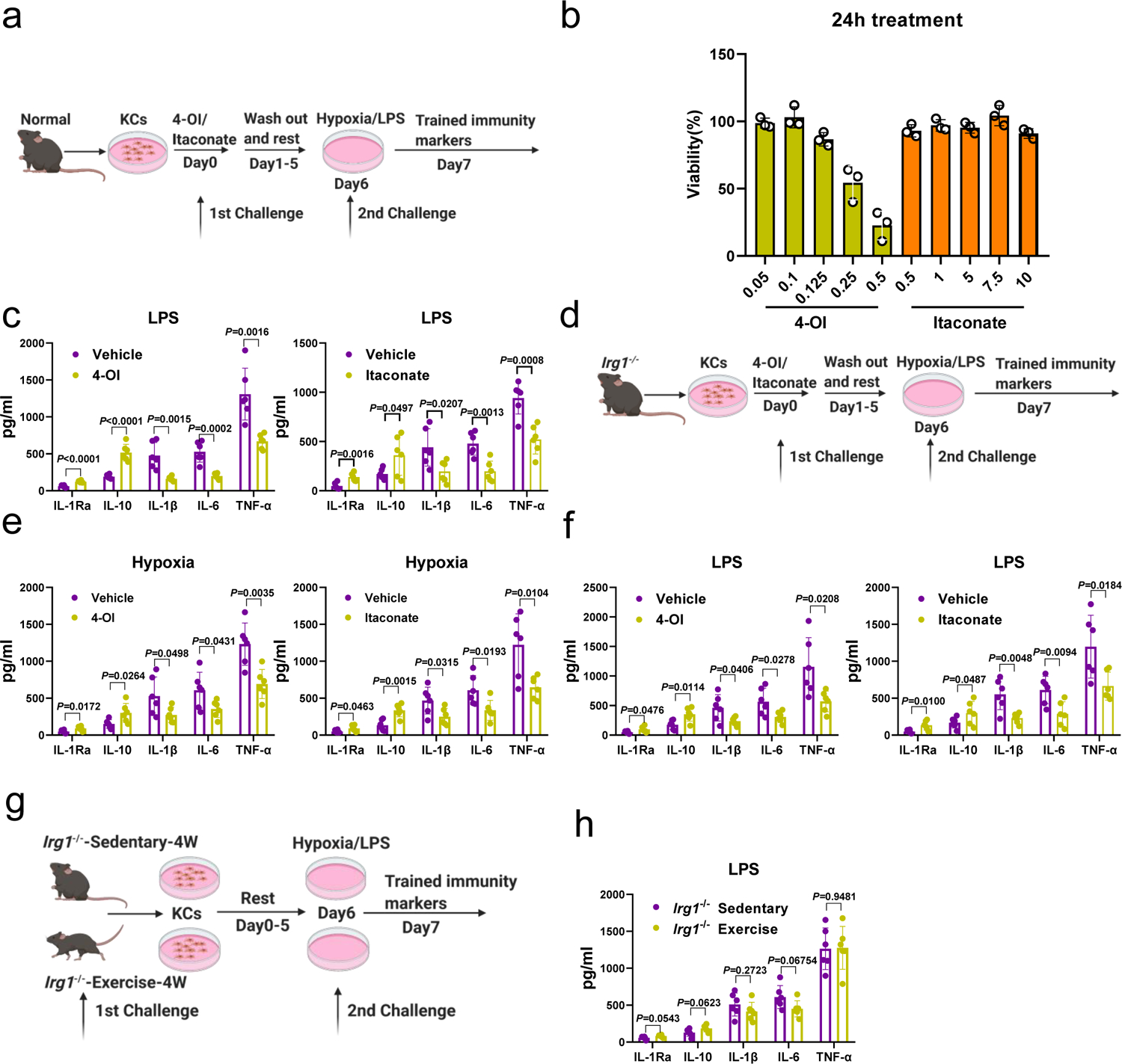

Fig. 6 |. Exercise Promotes an Anti-Inflammatory Trained Immunity in KCs.

a, Experiment outline. b-c, Trained immunity markers, IL-1Ra (P=0.9184, P=0.0076, P=0.0528, P=0.0002 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, before hypoxia, and after hypoxia) and IL-10(P=0.8057, P=0.0019, P=0.0543, P=0.0027 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, before hypoxia, and after hypoxia) (b); IL-1β (P=0.9405, P=0.0050, P=0.2220, P=0.0019 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, before hypoxia, and after hypoxia), IL-6 (P=0.6841, P=0.0029, P=0.3301, P=0.0003 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, before hypoxia, and after hypoxia) and TNF-α (P=0.7661, P=0.0024, P=0.7708, P=0.0014 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, before hypoxia, and after hypoxia) (c) from the medium of Kupffer cells which isolated from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) before and after the twice stimulation of hypoxia was measured by ELISA (n=6 mice per group). d-e, Medium levels of IL-1Ra (P=0.7236, P=0.0095, P=0.2891, P=0.0007 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, rest 7 days, and after IR) and IL-10 (P=0.1738, P=0.0070, P=0.7944, P=0.0011 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, rest 7 days, and after IR) (d); IL-1β (P=0.9405, P=0.0006, P=0.3176, P=0.0109 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, rest 7 days, and after IR), IL-6 (P=0.5193, P=0.0026, P=0.0575, P=0.0015 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, rest 7 days, and after IR) and TNF-α (P=0.9765, P=0.0061, P=0.9051, P<0.0001 between sedentary and exercise group at the time point of baseline, after exercise, rest 7 days, and after IR) (e) from Kupffer cells which isolated from mice with different time points: before and after sedentary or pre-operative exercise for 4 weeks, rest 7 days, with hepatic I/R were measured by ELISA (n=6 mice per group). f, IL-1Ra (P<0.0001 between Vehicle and 4-OI treatment, P=0.0369 between Vehicle and Itaconate treatment), IL-10 (P<0.0001 between Vehicle and 4-OI treatment, P=0.0468 between Vehicle and Itaconate treatment), IL-1β (P=0.0024 between Vehicle and 4-OI treatment, P=0.0470 between Vehicle and Itaconate treatment), IL-6 (P=0.0003 between Vehicle and 4-OI treatment, P=0.0463 between Vehicle and Itaconate treatment) and TNF-α (P=0.0004 between Vehicle and 4-OI treatment, P=0.0060 between Vehicle and Itaconate treatment) concentrations from the medium of normal Kupffer cells with the stimulation of PBS or 4-OI or itaconate after the challenge of hypoxia were measured by ELISA (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 per group). g, IL-1Ra (P=0.7418), IL-10 (P=0.8959), IL-1β (P=0.8300), IL-6 (P=0.8472) and TNF-α (P=0.0921) concentrations from the medium of Kupffer cells which isolated from Irg1−/− exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) after the challenge of Hypoxia were measured by ELISA (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). Graphs show the mean ± SD (b-g). Circles, triangles and squares represent individual mice. ANOVA with adjustment for multiple comparisons (b-e). Unpaired two-sample Student’s t test (f and g). All the statistical test used in this figure was two-sided and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Metabolic reprogramming of innate immune cells from oxidative phosphorylation towards aerobic glycolysis has been demonstrated as a critical mediator of the trained immunity22,50. Our data revealed pre-operative exercise protects mice from hepatic I/R injury via itaconate metabolism. We, therefore, hypothesized that pre-operative exercise initiated anti-inflammatory trained immunity in KCs via regulating itaconate metabolism. To test our hypothesis, we stimulated both Irg+/+ and Irg1−/− KCs with itaconate or 4-OI for 24 hours. After 5-day resting, KCs were re-stimulated with hypoxia or LPS (Extended Data Fig. 9a). We selected concentrations of itaconate (7.5 mM) and 4OI (0.1 mM) compounds for treatment, based on viability data (Extended Data Fig. 9b). We found that both itaconate- and 4-OI-stimulated Irg+/+ KCs produced significantly more anti-inflammatory cytokines and less pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to vehicle-stimulated control Irg+/+ KCs (Fig. 6f and Extended Data Fig. 9c). Both itaconate- and 4-OI-stimulated Irg1−/− KCs showed no difference in producing pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines compared to vehicle-stimulated Irg1−/− KCs after the re-stimulation with hypoxia or LPS (Extended Data Fig. 9d, e, f). Furthermore, Irg1−/− KCs from exercise mice showed no difference in producing pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines compared with sedentary Irg1−/− KCs after hypoxia or LPS challenge (Fig. 6g and Extended Data Fig. 9g, 9h), confirming that the itaconate metabolism is the main driver of the anti-inflammatory trained immunity in KCs. Collectively, our results demonstrate that the primary challenge pre-operative exercise induces an anti-inflammatory trained immunity in Kupffer cells via regulating the itaconate metabolism, which is responsible for protecting against the second challenge, hepatic I/R.

Discussion

Active lifestyle or long-term exercise training has been recognized to provide better outcomes with shortened recovery time after surgery. We show here that a limited pre-operative fitness training schedule will suffice for the same benefits as long-term exercise training. For example, in our mouse model, a 4-week exercise regimen is sufficient to yield the maximum beneficial effects of attenuating liver injuries and systemic inflammation under I/R. Lengthened pre-operative exercise therapy beyond four weeks does not necessarily provide additional benefits. Mice are also able to hold the same level of fitness for a 7-day resting period after 4-week pre-operative exercise therapy has been completed.

Despite the fact that pre-operative exercise strategy has been well approved by surgeons, current clinical research studies lack an integrated approach to explain how systemic pre-operative exercise therapy confers local beneficial effects and how it modulates the immune microenvironment to protect the organ from local surgical injury. We show here that exercise alters the hepatic immune microenvironment via metabolically reprogramming local resident macrophages, KCs, which then acquire a memorable an anti-inflammatory phenotype. Importantly, we also find that itaconate was the exercise regulated metabolite responsible for conferring the trained immunity to KCs. Thus, our findings unravel unknown mechanisms underlying pre-operative exercise and its beneficial effect on local organ injury after surgery.

Exercise training is known to create an anti-inflammatory environment by reducing the number of monocytes in the circulation and in the tissues, and suppressing the production of proinflammatory cytokines51,52. Our studies further indicate that pre-operative exercise therapy alters the hepatic immune microenvironment by reducing the numbers of infiltrating monocytes and neutrophils. Based on our single-cell RNAseq data, exercise alters only the transcriptomic profile of KCs and no other immune cells in the liver. Furthermore, our data demonstrated that KCs are required for the exercise-induced protective effect on hepatic I/R injury. Therefore, the decrease in the numbers of infiltrating monocytes and neutrophils may result from exercise induced anti-inflammatory phenotype in KCs. However, more in-depth studies are needed to confirm the association, as well as to understand why pre-operative exercise selectively induces an anti-inflammatory phenotype in KCs (resident macrophages) but not in other immune cells. Chronic exercise training has been reported to shift the immune phenotype of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory M1 state to an anti-inflammatory M2 state leading to the inhibition of inflammations in mouse liver53 and adipose tissue54. Beyond liver and adipose tissue, the inflammatory phenotype of residential macrophages in other organs such as lung and intestine may also be reformed since exercise is a systemic treatment. Our studies provide a framework to understand how exercise training modulates resident macrophages in other organs, which will create opportunities for devising exercise-based therapy to treat other inflammatory diseases.

Glycolysis and OXPHOS metabolic pathways are critical in deciding the immune phenotype of macrophages55. The available evidence for exercise-based changes in the cellular metabolism of immune cells is limited. Our results are consistent with a recent study that shows exercise therapy reprograms the metabolic profile in residential macrophages20. A few studies have shown that, during stress, the cellular metabolism shifts from OXPHOS towards glycolysis in macrophages, which results in the innate immune cell activation and proinflammatory cytokine secretion37,56. Here, we show that 4-week pre-operative exercise regimen confers the proinflammatory phenotype by switching the energy metabolism of KCs in the reverse direction, i. e., from glycolysis to OXPHOS, and thus induces an anti-inflammatory phenotype. Thus, our data provide mechanistic insights into pre-operative exercise actions and uncover that metabolic reprogramming, induced by exercise training, drives the residential macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype.

Activation of trained innate immunity often relies on the dynamic interplay between metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming24,57. Some of the TCA metabolites, such as α-ketoglutarate and itaconate, have been shown to induce epigenetic changes in immune cells44,58. Furthermore, a recent study reports that the generation of α-ketoglutarate epigenetically modulates the anti-inflammatory phenotype of lung residential interstitial macrophages in a mouse endotoxemia model59. We have shown here that the production of itaconate substantially increases after pre-operative exercise. It is conceivable that exercise induced itaconate may epigenetically drive the anti-inflammatory trained immunity in KCs. However, further studies are warranted to investigate whether and how epigenetic changes are involved in per-operative exercise induced trained immunity in KCs.

Recent studies show that 4-OI44 or itaconate, suppresses the inflammatory response to LPS stimulation by preventing the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages43,60. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in KCs contributes to liver damage and systemic inflammation after liver I/R39. Here we show that circulating IL-1β level is significantly lower in exercise mice than sedentary mice after liver I/R and LPS challenge. Therefore, it is predictable that pre-operative exercise may inhibit inflammasome activation via upregulating the production of itaconate. However, it is surprising that the circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines levels are significantly lower in the exercise mice compared with the sedentary mice even at baseline without liver I/R challenge, when inflammasome is not activated. These data suggest that itaconate can also drive an anti-inflammatory response independent of inflammasomes.

4-OI or exogenous itaconate treatment has been shown to improve metabolic homeostasis and confer an anti-inflammatory effect in various experimental I/R models, e. g., hepatic61 and cerebral I/R62, suggesting itaconate might provide a great clinical therapeutic potential. In macrophages, itaconate derivatives, such as 4-OI44 and dimethyl itaconate (DI)63, promote the anti-inflammatory effect via alkylating Nrf2 whereas other studies demonstrated a Nrf2 independent anti-inflammatory mechanism by directly using itaconate directly43,63. In other non-immune cells, such as hepatocytes61 and cortical neurons62, 4-OI treatment has also been shown to have a protective anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative responses to I/R injury by activating Nrf2 in hepatocytes or in primary cortical neurons. Our data indicate that pre-operative exercise activates Nrf2 in an IRG1 dependent manner. Notably, Nrf2 is required for the exercise induced beneficial effects on liver I/R injury. However, further studies are needed to understand the mechanisms underlying the itaconate/Nrf2-induced trained immunity and whether inflammasomes are also involved in this process.

In conclusion, our data unravel the mechanisms underlying the beneficial effect of pre-operative exercise by providing evidence that pre-operative exercise upregulates itaconate metabolism in KCs thereby inducing anti-inflammatory trained immunity, which overpowers inflammation and attenuates local organ injury. These findings open potential avenues for pre-operative exercise-based therapy in training innate immune cells to modulate inflammatory responses, moreover, provide molecular and cellular targets that can be exploited pharmaceutically to develop novel pre-operative exercise mimicking strategies for exercise-intolerant patients.

Methods

Animals.

Male wild-type (WT C57BL/6) mice Acod1em1(IMPC)J/J (Irg1−/−) mice, B6.129X1-Nfe2l2tm1Ywk/J (Nrf2−/−) and B6(Cg)-Tlr4tm1.2Karp/J (Tlr4−/−) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Mice were randomly assigned to experimental exercise or sedentary group between 8 and 10 weeks of age. For pre-operative exercise, eight to ten-week-old male mice were randomly divided into exercise and sedentary groups. For pre-operative exercise, the mice ran on a motorized treadmill (Columbus Instrument, Columbus, OH) with a modified exercise regimen at a speed of 12.5 m/min for 60 min/day, 5 days/week for 1 to 16 weeks64. All animal protocols were approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh as well as the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Ohio State University and performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of laboratory animals.

In vivo mouse models.

A nonlethal model of segmental (70%) hepatic warm ischemia and reperfusion was used34. Under sodium ketamine (100 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) anesthesia, a midline laparotomy was performed. The liver hilum was dissected free of surrounding tissue. All structures in the portal triad (hepatic artery, portal vein, bile duct) to the left and median liver lobes were occluded with a microvascular clamp (Fine Science Tools) for 60 min, and reperfusion was initiated by removal of the clamp. Throughout the ischemic interval, ischemia was confirmed by visualizing the pale blanching of the ischemic lobes. After the clamp was removed, gross evidence of reperfusion, which was based on immediate color change, was assured before closing the abdomen with continuous 4–0 polypropylene sutures. The temperature during ischemia was maintained at 31°C using a warming incubator chamber (Fine Science Tool). Sham animals underwent anesthesia, laparotomy, and exposure of the portal triad without hepatic ischemia. At the end of the observation period following reperfusion, the mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane and sacrificed by exsanguination. LPS challenge: Mice were injected intraperitoneally with a low dose of LPS (400 mg/kg) for 4 hours. KCs were depleted in exercise and sedentary mice by injecting sterile filtered gadolinium chloride (GdCl3, 25 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich)33 or vehicle (0.9% Saline Solution; fisher scientific) intraperitoneally 48 hours before liver I/R. Depletion of KCs was assessed at 48 hours by flow cytometry. For treating with itaconate, a cell-permeable itaconate analog, exercise or sedentary mice were administered intraperitoneally 4-OI (25 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 40% (2-Hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or itaconate (100 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich) or vehicle 24 and 2 hours before hepatic ischemia, and at the time of reperfusion. Sham animals underwent anesthesia, laparotomy, and exposure of the portal triad without hepatic ischemia.

Liver Damage Assessment.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (sALT) and serum aspartate transaminase (sAST) was measured using DRI-CHEM 4000 Chemistry Analyzer System (HESKA). To gauge liver damage, the liver tissues were harvested and subjected to histologic evaluation after hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining65. Samples were imaged and scored using the Suzuki methodology in a blinded manner by two individual examiners, who were unaware of the treatment group assignment of the animals, and quantified using a semiquantitative scoring system to assess liver damage39. The tissues were assessed for damage by measuring the amount (%) of inflammation, such as sinusoidal congestion, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and infiltrating inflammatory cells, and determining the degree of necrosis. The necrotic area was assessed quantitatively using ImageJ software (Version 1.53e) (National Institutes of Health). Results are presented as the mean percentage of necrotic area (mm2) with respect to the entire area of one capture (mm2).

Flow Cytometry.

Firstly, mouse liver non-parenchymal cells (NPCs) were isolated39,66. After laparotomy, the portal vein was cannulated, and the liver was flushed with HBSS (Invitrogen Life Technologies) supplemented with 0.96 g sodium bicarbonate (Perfusate I). Then, the liver was perfused with enzymatic solution of Collagenase, Type 1 (1 mg/ml) (Worthington-biochem) and for 10 min at 37 °C in a water bath with continuous agitation. After this treatment, the enzymatic solution was inactivated by adding DMEM-Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and was immediately centrifuged at 400 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The cell suspension was filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer, subjected to discontinuous Percoll gradient separation (Sigma-Aldrich). NPCs were separated from the hepatocytes by differential centrifugation (400 rpm for 5 min). The supernatant was centrifuged again (1500 rpm for 5 min x2) to obtain NPCs. Isolated cells were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies, Fixable Viability Dye eFluor™ 780 (eBioscience), PE-Cy-7 Rat Anti-mouse CD45 (30-F11, BD Biosciences), BUV395 Rat Anti-mouse Ly-6G(1A8, BD Biosciences), PerCP/Cy5.5-anti-mouse CD11b (M1/70, BioLegend), Pacific blue-anti-mouse CD19 (6D5, BioLegend), PE-anti-mouse F4/80(BM8, BioLegend), APC-anti-mouse NK1.1 (PK136, BioLegend), Alexa Fluor 700 Rat Anti-mouse CD3 (17A2, BioLegend), PerCP/Cy5.5-anti-mouse CD4 (GK1.5, BioLegend), and Pacific blue anti-mouse CD8a (53–6.7, BioLegend). Flow cytometry data were acquired using LSRFortessa Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson) with FASCDiva Software (Version 8.0.1, BD Pharmingen) and analyzed with Flowjo software (version 10). Flow cytometry data analysis is built upon the principle of gating as shown in Supplementary Figure. 1. Gates and regions are placed around populations of cells with common characteristics, usually forward scatter, side scatter and marker expression, to investigate and to quantify these populations of interest.

Kupffer Cells Isolation and Treatment.

Kupffer cells (KCs) were isolated from NPC fraction using (i) APC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD11b (M1/70, Biolegend) and anti-APC magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and then (ii) the depleted CD11b fraction was stained with APC-conjugated rat anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (BM8, Biolegend) and anti-APC magnetic beads67. For trained immunity analyses, KCs (3×106 cells per well) plated in 6-well plates, on day 1, either 10 mg/mL of β-glucan (Sigma) or PBS (Gibco) was added to the cultures for 24 hours. After 5 days of resting, KCs were re-stimulated with 10 ng/mL of LPS (Sigma) for 24 hours45. To simulate ischemia, KCs (3×106 cells per well) plated in 6-well plates were cultured under the hypoxic condition (1% oxygen) in an atmosphere-controlled chamber (MIC-101, patent no. 5352414) containing a gas mixture composed of 94% N2, 5% CO2, and 1% O2 for 24 hours. Cells were then reoxygenated under normoxic conditions (21% O2) in the standard cell culture incubator for 10 hours. For LPS and recombinant HMGB1 challenge, KCs (3×106 cells per well) plated in 6-well plates, cells were stimulated with ultra-pure LPS (10 ng/mL) or rHMGB1 (10 μg/mL) for 24 hours which were pre-mixed at room temperature for 20 min. For itaconate treatment, KCs (3×106 cells per well) plated in 6-well plates, cells were cultured with either 0.1 mM of 4-OI (Sigma) or 7.5 mM itaconic acid (Sigma) for 24 hours. Production of cytokines and chemokines were determined in the supernatants using commercial ELISA kits for IL1Ra, IL10, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (R&D Systems)48.

Depletion and Adoptive Transfer of Kupffer cells.

KCs depleted-Irg1+/+ exercise and sedentary mice served as recipients. Donor KCs were isolated from collagenase type I-perfused livers of exercise or sedentary Irg1+/+ mice, or exercise or sedentary Irg1−/− mice as described above. 1×105 KCs from sedentary-donors (Irg1+/+ or Irg1−/− sedentary mice) were transferred intravenously into each sedentary-recipient mouse 48 hours after KC depletion. 1×105 KCs from exercise-donors (Irg1+/+ or Irg1−/− exercise mice) were transferred intravenously into each exercise-recipient mouse 48 hours after KC depletion. Recipient mice were performed with hepatic I/R at 48 hours after donor KCs were adoptively transferred.

Mass Cytometry.

Two million mouse liver NPCs from exercise or sedentary mice were stained for mass cytometry analyses68. Antibodies were labeled with Maxpar® Mouse Sp/LN Phenotyping Panel Kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Fluidigm). Cells were fixed with Smart tube buffer for 10 min at room temperature, washed with cell staining media (CSM, Fluidigm), and incubated with surface antibodies for 50 min at RT. Cells were then washed three times with CSM, fixed with 1.5% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), and permeabilized with ice-cold methanol at −20°C for 15 min. Following incubation, cells were washed thrice with CSM and stained with intracellular antibodies for 50 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed twice with CSM and incubated in iridium intercalator pentamethylcyclopentadienyl-Ir (III)-dipyridophenazine (Fluidigm) Intercalator solution with 1.5% paraformaldehyde (1:4000 dilution) at 4°C until ready for analysis. Excess intercalator was removed by washing cells once with CSM and twice with deionized water. Cells were resuspended at a concentration of 1 million/ml of pure water mixed with 4 Elemental Equilibration beads (Fluidigm). Cells were acquired on a third-generation Helios mass cytometer at an event rate of 200–400 events per second. Noise reduction was utilized, sigma=3, and the event duration and lower convolution threshold were 8–150 and 600, respectively. Data were normalized and analyzed using Cytobank (Version 7.3.0)69. A compensation matrix was used to account for expected small (1–2%) spillovers from isotopic contamination in the metal isotopes. Data were evaluated using viSNE analysis in Cytobank70.

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing.

For 10X Genomics sample processing and cDNA library preparation, samples were prepared as outlined in the 10X Genomics Chromium user guide. Hepatic CD45+ cells were isolated from NPC fraction using CD45 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Next, the samples were washed twice in PBS (Life Technologies) + 0.04% BSA (Sigma) and resuspended in PBS + 0.04% BSA. Cell viability was assessed by staining with Trypan Blue (Invitrogen) and scoring on a hemocytometer (Thermo Fisher). Following counting, the appropriate volume for each sample was calculated for a target capture of 6000 cells. Samples below the required cell concentration as defined by the user guide (i.e., <400 cells/μl) were pelleted, resuspended, recounted, and volume adjusted with prior to loading onto the 10X Genomics single-cell-A chip kit, 16 rxns (PN-1000009, 10x genomics). After droplet generation with Chromium Single Cell 3’ Library & Gel Bead Kit v2, 4 rxns (PN-120267, 10x genomics) and Chromium i7 Multiplex Kit, 96 rxns (PN-120262, 10x genomics), samples were transferred onto a pre-chilled 96-well plate (Eppendorf), heat-sealed and reverse transcribed using a Veriti 96-well thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher). cDNA was recovered using Recovery Agent provided by the kit followed by a Silane DynaBead clean-up (Thermo Fisher) as outlined in the user guide. Purified cDNA was amplified for 12 cycles before cleaning using SPRIselect beads (Beckman). Samples were diluted 4:1 in elution buffer (Qiagen) and run on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) with Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit (reorder-no 5067–4626) and Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Chips (reorder-no 5067–4627) to determine the cDNA concentration. cDNA libraries were prepared as outlined by the Single Cell 3′Reagent Kit v2 (10X) user guide with appropriate modifications to the PCR cycles and based on the calculated cDNA concentration, as recommended by 10X Genomics.

Sequencing.

The concentration of each library was calculated based on the library size as measured using a bioanalyzer (Version B. 02. 08, Agilent Technologies) and qPCR amplification data (Kappa/Roche). Libraries were then pooled as 10 nM samples, diluted to 2 nM using elution buffer (Qiagen) with 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma), and denatured using an equal volume of 0.1 N NaOH (Sigma) for 5 min at room temperature. Library pools were further diluted to 20 pM using HT-1 (Illumina) before diluting to a final loading concentration of 14 pM. 150 μl of the 14 pM pool was loaded onto each well of an 8-well strip tube and loaded onto a cBot (Illumina) for cluster generation. Samples were sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 with the following run parameters: Read 1—26 cycles, read 2—98 cycles, index 1—8 cycles. A median sequencing depth of 60,000 reads/cell was targeted for each sample.

Gene Expression Analysis.

Preliminary sequencing results (bcl files) were demultiplexed and converted to FASTQ files with CellRanger mkfastq (CellRanger, version 2.1). The FASTQ files were aligned to the mm10 reference genome. We applied CellRanger (version 2.1) count/aggr for preliminary data analysis and generated barcode-gene count matrix. The R (version 4.0.0) and Seurat R package (version 3.0) were used for gene expression analysis. Cells with 2,500 genes and a mitochondrial gene percentage of >10% were excluded. After data normalization, PCA with variable genes was used as the input and identified significant principal components (PCs) based on the jackStraw function. Fifteen PCs were selected for clustering and non-linear dimension reduction. Cells were clustered by the FindClusters function and the FindAllMarkers function to find differentially expressed genes between each type of cell and group. Differential expressed genes between two clusters were generated by wilcoxon rank sum test with adjusted p-value < 0.05. The Do Heatmap function was used to draw the heatmaps. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was conducted by enrich GO function implemented in R package Clusterprofiler (version 3.16.1). Enriched pathways with adjusted p-value < 0.05 were visualized by dotplot function.

Metabolomics.

KCs (3×106 cells) from both exercise and sedentary mice were harvested for Metabolomics. The media was aspirated, and the cells were washed twice with LC-MS grade water before lysing the cells. The metabolites were extracted using a cold 80% methanol/water mixture and resuspended in 50% methanol/water mixture for further analysis using LC-MS/MS40. A selected reaction monitoring (SRM) LC-MS/MS method with positive and negative ion polarity switching on a Xevo TQ-S mass spectrometer was used for the analysis. Peak areas integrated using MassLynx 4.1 (Waters Inc.) were normalized to the respective protein concentrations. The resultant peak areas were subjected to relative quantitation analyses with MetaboAnalyst 5.0. Further, principal component analysis and pathway impact analysis and generating heatmaps were performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 software.

ELISA.

IL1Ra, IL10, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF- α, IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, CXCL1, CXCL2 and CXCL3 were measured in the serum using ELISA (R&D Systems) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Metabolic Flux Analysis.

The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of cells were measured using a Seahorse XFe24 extracellular flux analyzer. KCs were plated in XFe24 cell culture microplates at a density of 1*105 per well, with a total volume of 200 μl per well and grown to 80–90% confluence at the time of assay. Cells were incubated at 37°C overnight and then treated with 24 hours of hypoxia (1% O2) or LPS treatment. The medium was then replaced with Seahorse XF assay medium, and further experimental procedures were conducted as described by the manufacturer of the Real-Time ATP Rate Assay Kit and Mito Stress test kit. After measuring basal OCR and ECAR, OCR trace was recorded in response to oligomycin (1 μM), Carbonyl cyanide-p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 1 μM), and rotenone/antimycin (0.5 μM each) using the Real-Time ATP Rate Assay Kit and Mito Stress test kit (Agilent). After analysis with Wave software (Version 2.6.1, Agilent), the number of cells in each well was determined by nuclear DNA staining with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma), and OCR and ECAR values were normalized accordingly.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR.

Total mRNA was extracted from liver or cells using TRIZOL reagent (Cat. 15596–026, Invitrogen, USA), and cDNA was generated from 1 μg of RNA using an RT reagent kit (Cat. k1622, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Real-time PCR was performed using the Bio-Rad CFX96 Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) with SYBR-green (Cat.1725121, Bio-Rad, USA). All reactions were run in triplicate, and relative gene expression was calculated using the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method (relative gene expression = 2−(ΔCtsample-ΔCtcontrol)). The gene-specific primers used were forward 5′- GCGAACGCTGCCACTCA −3′ and reverse 5′-ATCCCAGGCTTGGAAGGTC-3′ for Irg1, and forward 5′-AGCCATGTACGTAGCCATCC-3′ and reverse: 5′-CTCTCAGCTGTGGTGGTGAA-3′ for β-actin. The relative expression level of mRNAs was normalized by the level of β-actin expression in each sample.

Western Blotting.

Whole-cell protein lysates from the liver and KCs were used for western blotting. Electrophoresis was used to separate complex mixtures of proteins on an SDS/PAGE and blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking in 5% BSA, the membranes were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with IRG1 (1:1000, Abcam ab222411), NRF2 (1:1000, cell Cell Signaling Technology 12721) and β-actin (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology 8457S) as an internal control. Proteins were visualized using IRDye® 800CW goat anti-rabbit 926–32211 (1: 10 000; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) or anti-mouse 800 antibody (1:10,000, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) secondary antibodies. Images were captured with the Odyssey CLx system (LI-COR Odyssey CLx, Lincoln, NE, USA). Uncropped scans of all blots are as shown in Source Data Figure. 1.

BioRender.

All experiment outlines are created with BioRender.com. The type of BioRender license used to create the figures is “Academic Subscription”. Our plan is “Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Plan”.

Statistical Analysis.

The data presented in the figures are mean ± SD. The treatment effects or the comparisons of chemokine/cytokines for two-group were compared using two-sample t test. For more than two-group experiments, one-way analysis of variance with post hoc tests were used to compare the differences between treatments. The repeated measurements were assessed by ANOVA analysis. Tukey method was used to adjust the multiple comparisons. The comparisons of categorical variables were evaluated using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. The baseline characteristics of each group were compared using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables (GraphPad Prism version 8). All the statistical test used in this manuscript was two-sided and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability.

We have deposited the Single Cell RNA-sequencing data associated with this study into Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with accession numbers (GSE 173429). All other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Pre-operative exercise reduces hepatic I/R injury and inflammation.

a, Liver damage were measured by serum AST level (P=0.7606, P=0.3610, P=0.0555, P=0.0549, P<0.0001, P<0.0001, P<0.0001, P<0.0001 between exercise and sedentary group from 1day to 16 weeks) and liver histological evaluation (Suzuki scores) ) (P=0.7464, P=0.1898, P=0.0932, P=0.0441, P<0.0001, P=0.0002, P<0.0001, P<0.0001between exercise and sedentary group from 1day to 16 weeks) from mice with sedentary or pre-operative exercise treatment for 1 day, or 1 to 16 weeks which subjected to hepatic I/R (n=6 mice per group). b, Liver damage were measured by plasma ALT (P=0.7548 in sham group, P<0.0001 in I/R group) and AST levels (P=0.2743 in sham group, P<0.0001 in I/R group) from mice with sedentary or pre-operative exercise treatment for 4 weeks which subjected to hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=7 mice in Sham group, n=11 mice in I/R group). c, Liver damage were measured by liver histological evaluation (necrotic areas and Suzuki scores) (for necrotic areas, (P=0.1228 in sham group, P<0.0001 in I/R group), for Suzuki scores, (P=0.8095 in sham group, P=0.0018 in I/R group) from mice with sedentary or pre-operative exercise treatment for 4 weeks which subjected to hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). d, Serum IL-1Ra (P=0.0001 in 4 weeks group, P=0.0008 in 8 weeks group, P=0.0005 in 12 weeks group, P=0.0006 in 16 weeks group), IL-10 (P=0.0008 in 4 weeks group, P=0.0002 in 8 weeks group P=0.0005 in 12 weeks group P=0.0002 in 16 weeks group), IL-1β (P=0.0004 in 4 weeks group, P=0.0003 in 8 weeks group, P=0.0002 in 12 weeks group, P=0.0005 in 16 weeks group), IL-6 (P=0.0015 in 4 weeks group, P=0.0011 in 8 weeks group, P=0.0007 in 12 weeks group, P=0.0012 in 16 weeks group) and TNF-α (P=0.0006 in 4 weeks group, P=0.0011 in 8 weeks group, P=0.0005 in 12 weeks group, P=0.0002 in 16 weeks group)concentrations were measured by ELISA from mice with sedentary or pre-operative exercise treatment for 4, 8, 12 or 16 weeks which subjected to hepatic I/R (n=6 mice per group). e, Serum IFN-α (P=0.0854 in sham group, P=0.04854 in I/R group), IFN-β (P=03053 in sham group, P=0.1154 in I/R group)and IFN-γ (P=0.1531 in sham group, P=0.0015 in I/R group) concentrations were measured by ELISA from mice with sedentary or pre-operative exercise treatment for 4 weeks at baseline (SHAM group) and subjected to hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). f, Serum CXCL1 (P<0.0001 in sham group, P<0.0001 in I/R group), CXCL2 (P=0.0040 in sham group, P=0.0001 in I/R group) and CXCL3 (P=0.0071 in sham group, P<0.0001 in I/R group) concentrations were measured by ELISA from mice with sedentary or pre-operative exercise treatment for 4 weeks at baseline (SHAM group) and subjected to hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). g, Liver damage were measured by serum AST level (P=0.0127 between sedentary and 0 day after exercise group, P=0.0001 between sedentary and 3 days after exercise group, P=0.0019 between sedentary and 5 days after exercise group, P=0.0082 between sedentary and 7 days after exercise group, p=0.4524 between 0 day and 3 days group, P=0.6955 between 0 day and 5 days group, P=0.9063 between 0 day and 7 days group, P=0.6701 between 3 days and 5 days group, P=0.5088 between 3 days and 7 days group, P=0.7702 between 5 days and 7 days group) from mice with sedentary or pre-operative exercise treatment for 4 weeks and resting for 0, 3, 5, or 7 days before hepatic I/R (Each dot represents one mouse, n=11 in sedentary group, n=7 in 0D after Exercise group, n=15 in 3D after Exercise group, n=9 in 5D after Exercise group, n=7 in 7D after Exercise group). Graphs show the mean ± SD (a to f). Circles, triangles and squares represent individual mice. ANOVA with adjustment for multiple comparisons for (a and d). Unpaired two-sample Student’s t test for (b, c, e and f). NS: not significant. All the statistical test used in this figure was two-sided and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Mass cytometry and flow cytometry characterize hepatic immune profile.

a, Mass cytometry (CyTOF) of hepatic immune microenvironment profile from exercise or sedentary mice (4 weeks) with or without hepatic I/R in t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) graph. b, Percentage of Kupffer cells (KCs), monocytes, and neutrophils out of hepatic CD45+ cells. (Each dot represents one mouse, n=2 mice per group) c, Percentage of neutrophils. d, Percentage of natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells, and CD3+ T cells out of hepatic CD45+ cells in each group. e, Numbers of B cells (P=0.3397 in sham group, P=0.8025 in I/R group), CD4+ T cells (P=0.6370 in sham group, P=0.3695 in I/R group), CD8+ T cells(P=0.7879 in sham group, P=0.6170 in I/R group), and NKT cells(P=0.6738 in sham group, P=0.3010 in I/R group), dendritic cells (DCs) (P=0.3910 in sham group, P=0.7954 in I/R group), out of hepatic CD45+ cells in each group (Each dot represents one mouse, n=6 mice per group). Circles and triangles represent individual mice. Graphs show the mean ± SD (b and e). Unpaired two-sample Student’s t test (b and e). All the statistical test used in this figure was two-sided and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.