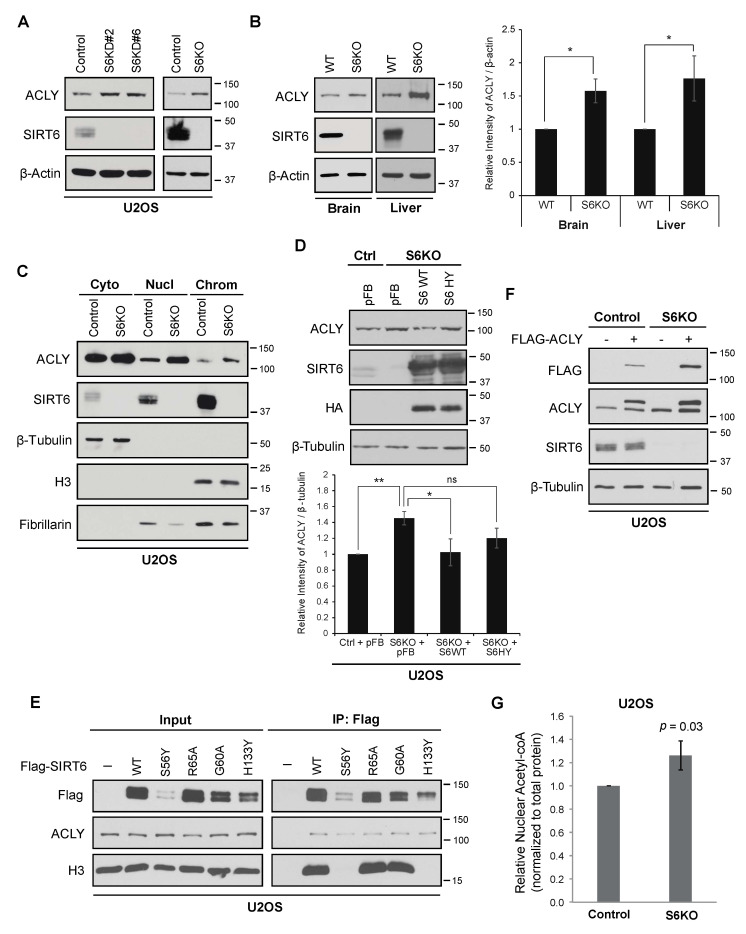

Figure 1.

ACLY level increases with SIRT6 depletion. (A). Increased ACLY protein levels in SIRT6-deficient U2OS cells generated by knockdown (KD) or Crispr/Cas9-mediated knockout (KO). (B). Increased ACLY protein expression in SIRT6 KO mice tissues with quantification (Mean ± SEM of three experiments, * p < 0.05, one-tailed Student’s t-test). (C). Sub-cellular fractionation showing increased levels of nuclear and chromatin ACLY in SIRT6 KO cells compared to controls. β-tubulin, fibrillarin, and Histone H3 are shown as markers for the cytoplasmic, nuclear, and chromatin-enriched fractions. (D). Increased ACLY in SIRT6 KO cells reversed by overexpression of SIRT6 WT but not SIRT6 HY mutant with quantification (Mean ± SEM of three experiments, * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; ns: not significant, one-tailed Student’s t-test). pFB, empty vector control. (E). Co-IP of ACLY with Flag-tagged wild-type (WT) and catalytically inactive SIRT6 proteins overexpressed in U2OS cells. The S56Y and H133Y mutations abolish SIRT6 catalytic activity, whereas R65A and G60A have partially impaired deacetylase and ADP-ribosyl transferase activities. The Histone H3 levels show chromatin association of the SIRT6 proteins. (F). Increased abundance of Flag-ACLY and endogenous ACLY protein in SIRT6 KO cells. (G). Relative nuclear Acetyl-CoA levels in control and SIRT6 KO cells, normalized to total protein (Mean ± SEM of seven experiments, two-tailed Student’s t-test).