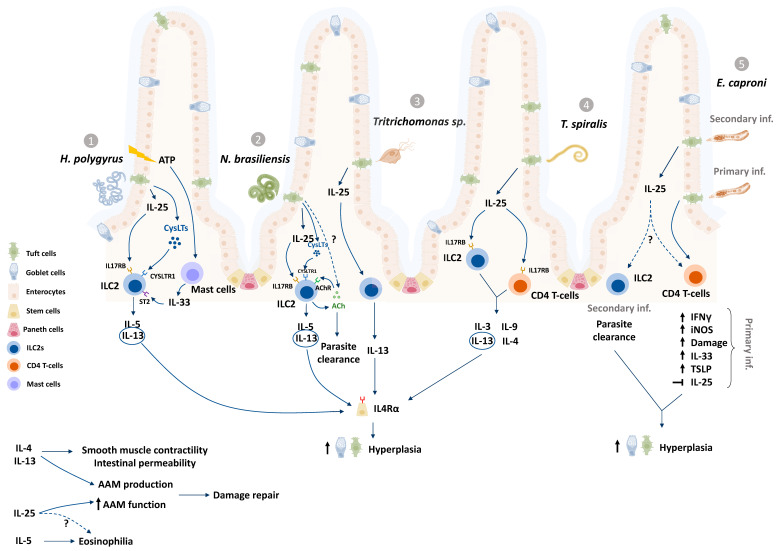

Figure 1.

Enteric tuft cells (ETCs) have been studied in murine infection models with the nematodes Heligosmoides polygyrus (1), Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (2), and Trichinella spiralis (4); the trematode Echinistoma caproni (5), and the protozoan Tritrichomonas (3). In response to helminths and protozoans, ETCs produce and release IL-25 (1-4) and cysteinyl leukotrienes (1,2), which subsequently activate the innate lymphoid cell (ILC2) population in the underlying lamina propria via IL-17RB and CYSLTR receptors to produce IL-13, IL-5 and IL-9 [6,7,9,57,64]. IL-13 induces intestinal stem cell differentiation via IL-4Rα signaling, causing ETC and goblet cell hyperplasia (see Figure 2 for approximate timelines), increased smooth muscle contractility and intestinal permeability amongst other mechanisms that aid parasite expulsion [5,9]. Mast cells sense damage related release of ATP and release IL-33 to activate ILC2 production of IL-13 (1) [43]. ILC2s also produce and release acetylcholine (ACh) in response to infection with N. brasileinsis and are activated by ACh to produce IL-13 (2) [65,66]. Although ETC hyperplasia is observed after primary and secondary infection with E. caproni, Il-25 expression is upregulated in the acute secondary infection rather than the chronic primary infection, which is characterized by increased levels of Th1 cytokine mRNA (5) [10,53,63]. ETC-derived mediators may also act on other cell types such as eosinophils and macrophages (alternatively activated macrophages, AAM), to coordinate repair, as well activate CD4 T cell populations (4,5) to release cytokines during parasitic infections [48,67,68,69].“?” represents mechanisms that are yet unknown in tuft cell literature.