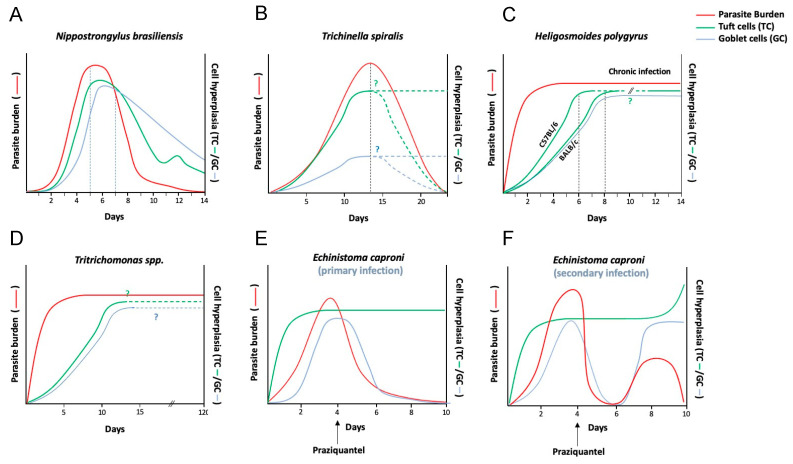

Figure 2.

Dynamics of parasite clearance, tuft cell hyperplasia and goblet cell hyperplasia during parasitic infections. In some acute enteric infections, such as with (A,B) N. brasiliensis and T. spiralis (intestinal phase) the events of enteric tuft cell (ETC) hyperplasia and goblet cell hyperplasia precede or happen around the same time as worm expulsion/reduction in worm burdens [6,8,9,80,81]. In chronic parasitic infections however, such as with (C) H. polygyrus [6,9,46,82,83], (D) the protozoan Tritrichomonas [59] and (E) E. caproni [55], ETC hyperplasia persists for as long as parasite burden persists [7,10,23] and may also coincide with goblet cell hyperplasia [7,10,56]. It remains to be tested whether ETC hyperplasia (as well as goblet cell hyperplasia) serves to either induce immunity against secondary/concomitant infections or mediate repair of damaged intestinal tissue [23]. ETC hyperplasia in parasitic models of infection may be the downstream effect of a Th2 cascade (dominated by increased IL-13 production in the intestinal niche) [9] with the exception of the (E,F) E. caproni trematode model of murine infection, where primary host response is Th1 cytokine centric [53], and ETC hyperplasia is observed in both primary infection as well as secondary infection after drug clearance (praziquantel) [10]. Graphs represent hypothetical temporal kinetics of worm burden, tuft cell and goblet cell numbers based on individual time point data presented in literature, where “?” and dotted lines represent estimation of trendlines at time points where data was unavailable.