Abstract

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is the leading cause of secondary osteoporosis. Although bone mineral density (BMD) tends to recover after parathyroidectomy in PHPT patients, the degree of recovery varies. Circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) profiles are known to be correlated with osteoporosis and fracture. We aimed to investigate whether osteoporotic fracture-related miRNAs are associated with postoperative BMD recovery in PHPT. Here, 16 previously identified osteoporotic fracture-related miRNAs were selected. We analyzed the association between the preoperative level of each miRNA and total hip (TH) BMD change. All 12 patients (among the 18 patients enrolled) were cured of PHPT after parathyroidectomy as parathyroid hormone (PTH) and calcium levels were restored to the normal range. Preoperative miR-19b-3p, miR-122-5p, and miR-375 showed a negative association with the percent changes in TH BMD from baseline. The association remained robust for miR-122-5p and miR-375 even after adjusting for sex, age, PTH, and procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide levels in a multivariable model. In conclusion, preoperative circulating miR-122-5p and miR-375 levels were negatively associated with TH BMD changes after parathyroidectomy in PHPT patients. miRNAs have the potential to serve as predictive biomarkers of treatment response in PHPT patients, which merits further investigation.

Keywords: microRNA, primary hyperparathyroidism, bone mineral density

1. Introduction

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT), a leading cause of secondary osteoporosis, is characterized by hypercalcemia and bone loss owing to the overproduction of parathyroid hormone (PTH) [1,2]. In patients with PHPT, the only curative treatment is surgery [3]. Previous studies reported that the risk of fracture reduced and bone density improved in patients who underwent parathyroidectomy as opposed to patients who did not [3,4]. However, there is a large variance in bone mineral density (BMD) changes after parathyroidectomy among PHPT patients [5,6]. Sharma and colleagues demonstrated that BMD reduced after surgery in 31% of patients with PHPT [5]. PTH alone does not explain all changes in BMD after surgery [5,7]. Although alkaline phosphatase (ALP), type 1 cross-linked C-terminal telopeptide collagen (CTx), and procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) have been suggested as predictors of BMD changes after surgery in PHPT patients, these observations remain controversial [6,8,9,10].

In clinical situations, anti-osteoporotic medications are not started immediately after parathyroidectomy in most patients with PHPT. This results from concerns about anti-resorptive or anabolic medications that may interfere with postoperative BMD recovery. Anti-resorptive drugs inhibit and reduce osteoblast activity owing to the lack of osteoclast-derived coupling factors [11]. Moreover, there have been no studies other than with strontium ranelate on the use of anabolic drugs within 1 year after surgery in patients with PHPT [12]. However, considering the high risk of fracture immediately after surgery [13], biomarkers that can predict postoperative BMD improvement may help to preemptively consider anti-osteoporotic drugs.

Recently, microRNAs (miRNAs) and non-coding single-stranded RNA molecules, which are known to regulate gene expression through post-transcriptional modification, have emerged as novel noninvasive disease biomarkers [14,15]. Circulating miRNAs in human plasma are protected from endogenous RNase activity and are stable [16]. In previous reports, miRNAs have been suggested as major regulators of bone metabolism [17,18,19,20,21,22]. miRNAs associated with osteoporotic fractures have also been thought to be associated with bone deterioration [23,24,25]. These osteoporotic fracture-related miRNAs can be predictors of postoperative BMD changes in patients with PHPT.

Thus, in this study, we investigated whether osteoporotic fracture-related miRNAs can predict postoperative BMD changes in patients with PHPT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Among the 164 patients who underwent parathyroidectomy for PHPT at Severance Hospital between July 2017 and April 2019, 18 were selected and enrolled in the study. The following groups were also excluded from the study: (i) patients who were administered a drug known to affect bone metabolism, such as bisphosphonate, denosumab, calcimimetics, glucocorticoid, thiazolidinedione, thiazide, antidepressant, lithium, aromatase inhibitor, and estrogen at the time of blood collection; (ii) patients who did not undergo dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for BMD measurement 1 year after parathyroidectomy; (iii) patients who had samples with hemolysis ratio higher than 7 or visible hemolysis; (iv) patients who had a history of liver failure, chronic kidney disease stage 4 and above, metabolic bone disease, and other uncontrolled endocrine diseases affecting bone metabolism; (v) patients who had a family history of PHPT or multiple endocrine neoplasia 1; (vi) patients who had experienced any fractures in the last 6 months; and (vii) patients with atypical parathyroid adenoma or parathyroid carcinoma confirmed in the histopathologic report.

BMD was measured using (DXA) (Discovery W, Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) at the lumbar spine (LS), femoral neck (FN), and total hip (TH) at baseline and post 1 year after parathyroidectomy. The coefficients of variation (CVs) in our institution for areal BMD at LS, FN, and TH were 1.2%, 2.1%, and 1.7%, respectively. The primary outcome of the study was the association of each osteoporotic fracture-related miRNA with the percentage change in TH BMD (%) at 1 year after surgery for the following reasons: (i) there is a greater reduction of cortical bone than cancellous bone in patients with PHPT [26,27,28,29]; (ii) TH BMD is one of the regions that improves 1 year after parathyroidectomy [30]; and (iii) CVs for TH BMD are lower than that for FN in our hospital, which is consistent with the reported literature (CV for TH BMD, 0.8–1.7%; CV for FN BMD, 1.1–2.2%) [31]. The association between each miRNA and percentage changes in LS BMD and FN BMD from baseline, 1 year after surgery, were analyzed as secondary outcomes. The serum CTx level was measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Elecsys β-CrossLaps; Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland; intra-assay CV < 3.5%, inter-assay CV < 8.4%). PTH and P1NP levels were also measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA; Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland; PTH intraassay CV < 2.5%, PTH inter-assay CV < 5.7%; P1NP intra-assay CV < 3.6%, inter-assay CV < 3.9%).

Osteoporosis, osteopenia, and normal BMD were classified according to the International Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines [32]. The T-score was applied for postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years and older, and Z-score was applied for premenopausal women and men aged < 50 years.

2.2. Circulating miRNA Analysis

Overnight fasting blood samples were collected 0–2 days before surgery and stored at −80 °C in the Yonsei University College of Medicine. Selected osteoporotic fracture-related miRNAs were extracted and amplified from plasma according to the manufacturer’s instructions and methods, as described in the literature [33,34].

The miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen) was used for purification of cell-free total RNA. Briefly, plasma samples were thawed on ice and 1 mL lysis reagent was added to 200 µL sample. Isolated RNA was used for reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using the miRCURY LNA RT Kit (Qiagen). The isolated RNA was thawed and mixed with 5× miRCURY RT reaction buffer followed by 10× miRCURY RT Enzyme. To adjust each template RNA to 5 ng/μL, we used 2 μL of the eluate for 200 μL of the plasma samples. After mixing the reverse transcription master mix on ice, the samples were incubated for 60 min at 42 °C and then incubated for 5 min at 95 °C to inactivate the reverse transcriptase enzyme. After cooling to 4 °C, RT-PCR was performed. PCR conditions were: 95 °C for 2 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, and 56 °C for 1 min.

Sixteen circulating miRNAs (hsa-miR-19b-3p, hsa-miR-21-5p, hsa-miR-23a-3p, hsa-miR-23a-5p, hsa-miR-24-2-5p, hsa-miR-24-3p, hsa-miR-93-5p, hsa-miR-100-5p, hsa-miR-122-5p, hsa-miR-124-3p, hsa-miR-125b-5p, hsa-miR-148a-3p, hsa-miR-152-3p, hsa-miR-335-5p, hsa-miR-375, and hsa-miR-532-3p), which were reported to be upregulated in the serum of patients with osteoporotic fracture, were selected [24,33].

The 5s ribosomal RNA (5s rRNA) and miR-16 were used as housekeeping genes, and the stability of the reference gene transcripts was calculated using Delta Ct, BestKeeper, Normfinder, and Genorm algorithms [35,36,37,38]. The 5s rRNA gene was identified as a stable housekeeping gene. All analyses were based on the baseline value (2−∆Ct). Ct values were normalized to the internal control, and miRNA expression was presented as ∆Ct = (Ct gene of interest—Ct internal control). If the miRNA Ct was ≥40, the value was considered undetermined and was set to ∆Ct = 40. Samples with a hemolysis ratio (calculated by Cthsa-miR-23a-3p minus Cthsa-miR-451a) of higher than 7 were excluded from the final analysis [33].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Logarithmic transformation (log 2) was used for miRNA analysis. The paired-sample t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to compare continuous variables, as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed to evaluate the association of each miRNA with BMD gain at 1 year after adjustment for age, sex, and baseline PTH level. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 16.0 (Stata Corp LP., College Station, TX, USA). A two-sided p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.4. Target Gene Predictions

Potential target mRNAs for the selected miRNAs were identified via bioinformatics using four different algorithms within the miRWalk3.0 database, namely miRWalk, TargetScan, miRDB, and miRTarBase [39].

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Study Subjects

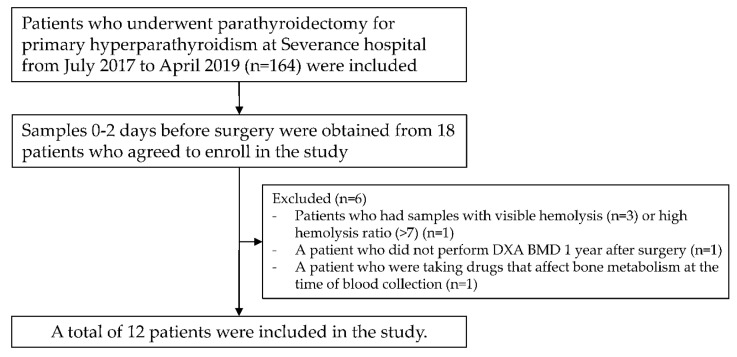

A total of 12 patients with PHPT (10 women, mean age 55.2 years) were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Of the 10 women, 7 were postmenopausal and 3 pre-menopausal. Among the two men, one was above 50 years of age and the other below 50 years of age. According to baseline BMD, three patients had osteoporosis, four patients had osteopenia, and five patients had normal BMD (Table 1). Each patient underwent surgical treatment for the following reasons. Four patients were <50 years old, seven patients had serum calcium levels > 1 mg/dL compared to the normal range, two patients had estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60, one patient had nephrolithiasis, and five patients had a T-score of −2.5 or less. Among the five patients with a T-score of −2.5 or less, two had a forearm T-score of −2.5 or less. One patient was provided surgical treatment because she wanted surgical treatment, and bone loss was progressed. All patients were successfully cured of PHPT as PTH and corrected Ca levels improved to normal ranges within 1–3 days after surgery (median PTH, 109.7 to 40.6 pg/mL, p < 0.001; median corrected calcium, 11.0 to 9.1 mg/dL, p = 0.001). P1NP, CTx, and 25-OH-vitamin D were also significantly recovered 2 weeks after surgery (median P1NP, 72.5 to 91.8 ng/mL, p = 0.003; median CTx, 0.665 to 0.390 ng/mL, p = 0.002; mean 25-OH-vitamin D, 19 to 27 ng/mL, p = 0.001). Serum calcium levels were maintained in the normal range for more than 6 months after surgery, and we decided that PHPT patients were cured.

Figure 1.

Outline of the study design.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Variables | Total (n = 12) |

|---|---|

| % Female (n) | 83.3% (10) |

| Age (years) | 55.2 ± 14.9 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.3 ± 3.5 |

| Osteoporosis/Osteopenia/Normal, n (%) | 3 (25%)/4 (33%)/5 (42%) |

| Laboratory tests (reference value) | |

| P1NP, ng/mL (23–83) | 72.5 (44.6–100.6) |

| CTX, ng/mL (<0.573) | 0.665 (0.406–1.125) |

| PTH, pg/mL (15–65) | 109.7 (96.9–157.8) |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL (>20) | 18.9 ± 5.5 |

| Corrected Ca, mg/dL (8.5–10.5) | 11.6 (9.8–12.4) |

| Phosphate, mg/dL (2.8–4.5) | 2.9 (2.6–3.1) |

| ALP, IU/L (52–133) | 89.8 ± 23.0 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 (≥60) | 104 (76–110) |

| Urinary Ca, mg/24 h (70–180) | 227 ± 105 |

Data are presented as frequency (%), mean ± standard deviation, and median (interquartile ranges). Abbreviations: P1NP, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide; CTX, C-terminal telopeptide; PTH, parathyroid hormone; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; Ca, calcium; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate calculated by EPI.

3.2. Correlation between miRNAs and Study Covariates

The relationships between age, PTH, CTx, P1NP, and each miRNA are shown as a heat map (Supplementary Figure S1). Although none of the miRNAs were significantly associated with age, baseline PTH, CTx, and P1NP (p > 0.05), there was a high correlation between most of the miRNAs, indicating that the selected miRNAs in this study were indeed involved in bone metabolism. All miRNAs, except miR-122-5p and miR-124-3p, showed statistically significant associations with each other (p < 0.05).

3.3. Higher Preoperative Circulating miR-122-5p and miR-375 Expression Levels Were Associated with Slow Recovery of TH BMD in Patients with PHPT

The association between each miRNA and postoperative TH BMD percent change from baseline, 1 year after parathyroidectomy, is described in Table 2. In univariable regression, miR-19b-3p (β coefficient = −1.55, p = 0.038), miR-122-5p (β coefficient = −1.61, p = 0.034), and miR-375 (β coefficient = −2.12, p = 0.002) were negatively associated with change in TH BMD. After adjustment for age, sex, PTH, and P1NP (Table 3, model III), the association among miR-122-5p, miR-375, and TH BMD changes was significant, whereas no association was observed between miR-19b-3p and TH BMD changes. According to the pre-specified panel, miR-122-5p and miR-375 commonly targeted runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) in the predicted target model (Supplementary Materials Table S1). There was no association between each miRNA and LS BMD or FN BMD changes after surgery in patients with PHPT (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2.

Univariable regression (β coefficient) for the association of log-transformed preoperative miRNAs (−∆Ct) with total hip bone mineral density (TH BMD) percent change from baseline (%), 1 year after parathyroidectomy, in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT).

| Change in TH BMD from Baseline (%)—1 Year after Surgery | β Coefficient | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-19b-3p | −1.55 | 0.038 * |

| hsa-miR-21-5p | −1.11 | 0.282 |

| hsa-miR-23a-3p | −0.69 | 0.447 |

| hsa-miR-23a-5p | 0.22 | 0.893 |

| hsa-miR-24-2-5p | −0.58 | 0.432 |

| hsa-miR-24-3p | −0.85 | 0.274 |

| hsa-miR-93-5p | −1.33 | 0.113 |

| hsa-miR-100-5p | −1.02 | 0.273 |

| hsa-miR-122-5p | −2.12 | 0.002 * |

| hsa-miR-124-3p | 1.94 | 0.319 |

| hsa-miR-125b-5p | −1.14 | 0.395 |

| hsa-miR-148-3p | −1.26 | 0.18 |

| hsa-miR-152-3p | −1.37 | 0.227 |

| hsa-miR-335-5p | −0.68 | 0.561 |

| hsa-miR-375 | −1.61 | 0.034 * |

| hsa-miR-532-3p | −0.77 | 0.463 |

* indicates a significant association between miRNAs and changes in BMD.

Table 3.

Multivariable regression models for TH BMD change from baseline (%), 1 year after parathyroidectomy, in patients with PHPT.

| Change in TH BMD from Baseline (%) | Model I | Model II | Model III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | β coefficient (95% CI) |

p-value | β coefficient (95% CI) |

p-value | β coefficient (95% CI) |

p-value |

| miR-19b-3p | −1.55 (−2.99 to −0.10) |

0.038 | −1.31 (−2.71 to 0.08) |

0.062 | −1.08 (−2.26 to 0.10) |

0.067 |

| miR-122-5p | −2.12 (−3.29 to −0.95) |

0.002 | −3.00 (−4.56 to −1.45) |

0.002 | −2.60 (−3.88 to −1.32) |

0.003 |

| miR-375 | −1.61 (−3.08 to −0.15) |

0.034 | −1.62 (−2.80 to −0.44) |

0.013 | −1.34 (−2.25 to −0.43) |

0.011 |

Model 1: No adjustment. Model 2: Adjusted for age and sex. Model 3: Adjusted for age, sex, PTH, and P1NP. Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PTH, parathyroid hormone transformed by natural logarithm; P1NP, procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide.

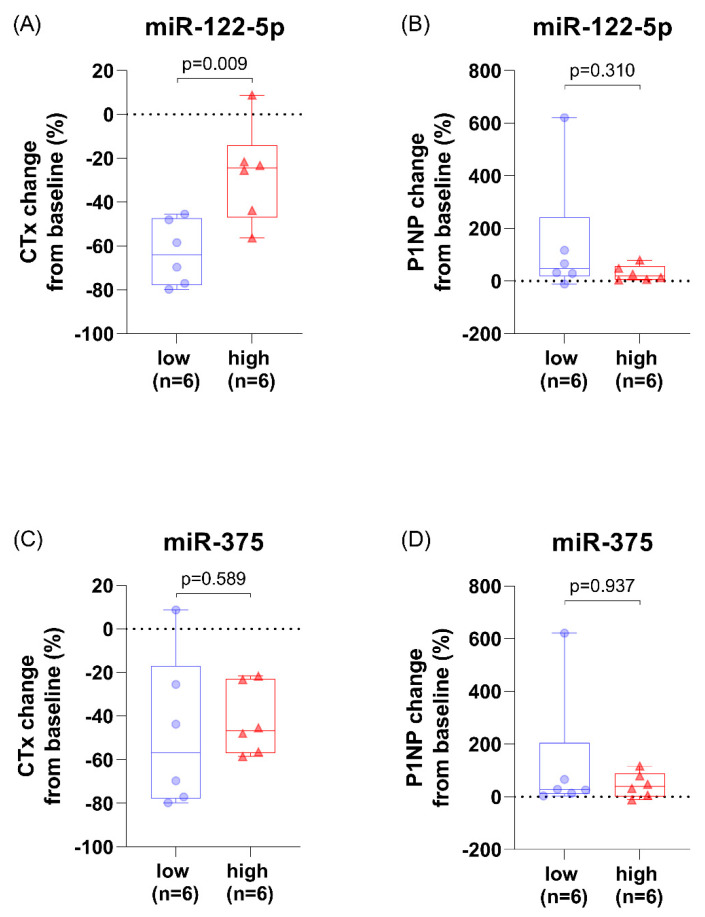

3.4. Patients with High miR-122-5p Levels Had Less CTx Change after Parathyroidectomy

In patients with higher preoperative miR-122-5p levels, the postoperative CTx change (%) from baseline, 2 weeks after surgery, was smaller (p = 0.009). There was no difference in the postoperative P1NP change (%) from baseline with respect to miR-122-5p levels (p = 0.310). There was no difference in CTx and P1NP changes after surgery with respect to miR-375 levels (p > 0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Change in bone turnover markers from baseline (%), 2 weeks after parathyroidectomy, with respect to miR-122-5p and miR-375 levels in patients with PHPT. (A) The postoperative CTx change (%) with respect to miR-122-5p levels. (B) The postoperative P1NP change (%) with respect to miR-122-5p levels. (C) The postoperative CTx change (%) with respect to miR-375 levels. (D) The postoperative P1NP change (%) with respect to miR-375 levels. Abbreviations: C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX) and procollagen type 1 N propeptide (P1NP).

3.5. Association between Known Predictors of BMD Response and Postoperative BMD Changes in Patients with PHPT

Predictive markers related to BMD change after parathyroidectomy in patients with PHPT, such as corrected calcium, bone turnover markers (CTx, P1NP), PTH, and age were used in the analysis. Upon conducting the Spearman correlation analysis, corrected calcium was associated with postoperative TH BMD changes (ρ = 0.608, p = 0.036). CTx and P1NP were associated with postoperative FN BMD changes (CTx, ρ = 0.587, p = 0.045; P1NP, ρ = 0.587, p = 0.045). PTH, age, and sex were not significantly correlated with postoperative BMD changes (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

In this proof-of-concept study, we investigated whether osteoporotic fracture-related miRNAs were associated with the degree of postoperative BMD changes in patients with PHPT. Previous studies reported potential markers associated with BMD changes after parathyroidectomy in PHPT patients, but the results are inconsistent among studies. Lumachi et al. suggested that premenopausal women had a greater LS BMD (L2-4) gain than postmenopausal women [40]. Koumakis et al. reported a correlation between ALP and BMD improvement [8]. Alonso et al. reported that PTH, CTx, and P1NP levels were associated with changes in LS BMD in simple regression analysis in 53 PHPT patients [9]. By contrast, Steinl et al. suggested that preoperative serum calcium levels, total parathyroid weight on computed tomography, sestamibi avidity, and time from pre- to post-operative DXA are associated with LS BMD improvement after surgery, but not PTH levels [41]. Owing to these controversies, we evaluated whether miRNAs can be used as new markers for postoperative BMD recovery in PHPT patients.

The selected osteoporotic fracture-related miRNAs in our study are known to be involved in bone metabolism; miR-19b-3p and miR-335-5p stimulate osteogenic differentiation [42,43], whereas miR-23a, miR-24-3p, miR-100-5p, miR-125b-5p, and miR-532-3p inhibit osteogenic differentiation [44,45,46,47,48]. Mir-124-3p inhibits osteoclastogenesis by suppressing the nuclear factor of activated T cells 1 (NFATc1) and the receptor activator of nuclear factor k-B ligand (RANKL)-mediated osteoclast differentiation and osteoblastogenesis, by suppressing distal-less (Dlx) [49,50]. MiR-148-3p promotes both osteoclast differentiation via V-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B (MAFB) and osteogenic differentiation via lysine-specific demethylase 6b (Kdm6b) [51,52]. Inhibition of miR-152 promotes osteoblast differentiation [53]. In the present study, most of the selected miRNAs showed a strong correlation with each other, suggesting that they were involved in similar processes of bone metabolism.

Among the selected osteoporotic fracture-related miRNAs, we found that high miR-122-5p and miR-375 levels were associated with lower postoperative TH BMD changes independent of age, sex, PTH, and P1NP. This is consistent with recent clinical studies that have revealed that miR-122-5p and miR-375 are associated with bone deterioration. miR-122-5p was upregulated in 15 postmenopausal women with hip fracture compared to 12 postmenopausal women with osteoarthritis [54], and was also upregulated in 45 osteoporotic patients with fracture compared to 15 non-osteoporotic patients with fracture [55]. In a study of 30 osteoporosis and 30 non-osteoporosis patients, miR-122a had the highest risk of osteoporosis, with the area under the curve of 0.77 among miR-21, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-93, miR-100, miR-122a, miR-124a, miR-125b, and miR-148a [24]. Meanwhile, Mandourah et al. reported that miR-122-5p is downregulated in osteoporosis (with or without fracture) in a study of 139 patients older than 40 years, which is inconsistent with our study [56]. This difference may result from the inclusion of a small number of patients with fracture or steroid exposure 2 years to 1 month prior to the time of study registration in the study of Mandourah et al. [56]. miR-375 was upregulated in 26 patients with low BMD and vertebral fractures compared to 42 healthy postmenopausal women [33]. In a study of 50 osteoporotic and 49 non-osteoporotic women, high levels of miR-375 were associated with a high risk of osteoporosis [57].

According to target gene predictions (Supplementary Table S1), miR-122-5p and miR-375 commonly target RUNX2, which is necessary for osteoblast differentiation [39,58]. Patients with relatively high levels of miR-122-5p and miR-375 might have decreased RUNX2 levels, which might adversely affect osteoblast differentiation after parathyroidectomy in patients with PHPT. Several studies provide evidence that miR-122-5p and miR-375 are associated with RUNX2 and osteoblast differentiation. In an in vitro study, miR-375 inhibited osteogenic differentiation by targeting RUNX2, and this result is consistent with that of our study [59]. Sun et al. demonstrated that miR-375 suppresses osteogenesis by targeting low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) and β-catenin [60]. However, the effect of miR-122-5p on osteoblast differentiation remains controversial. Meng et al. demonstrated that miR-122 inhibits osteoblast proliferation by activating the Purkinje cell protein 4 (PCP4)-mediated c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway [61]. By contrast, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes carrying miR-122-5p promote osteoblast proliferation in osteonecrosis of the femoral head, regulating Sprouty RTK Signaling Antagonist 2 (SPRY2) via the RTK/Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway [62]. The relationship between miR-122-5p and RUNX2 has not yet been investigated.

Interestingly, in this study, PHPT patients with high miR-122-5p levels had significantly less change in CTx 2 weeks after surgery. Patients with high miR-122-5p levels had relatively high CTx levels within two weeks of surgery, adversely affecting BMD recovery. CTx is cleaved by osteoclasts during bone resorption, which suggests a link between miR-122-5p and osteoclasts [63]. Kelch et al. reported that miR-122-5p is upregulated in osteoporotic osteoclasts during osteoclast differentiation compared to non-osteoporotic cells [64], which is in close agreement with our findings. However, the direct effect of miR-122-5p on osteoclastogenesis has not yet been documented. In addition, it may be an effect of RUNX2 degradation. RUNX2 has been suggested to be a major modulator of osteoblast differentiation, and, recently, Xin et al. reported that this modulation occurs via the AKT/NFATc1/CTSK axis [65]. MiR-122-5p may reduce both osteoblast and osteoclast differentiation through RUNX2 degradation, although there was no difference in P1NP change with respect to the miR-122-5p levels in the present study. In fact, P1NP change 2 weeks after surgery may reflect the increased procollagen type I synthesis as the PTH decreases. In PHPT patients, continuous PTH elevation increases the osteoblastic population and osteoblasts synthesize procollagen type I, while PTH plays a role in preventing the synthesis of procollagen type 1 in osteoblast itself [66,67]. Therefore, immediately after surgical treatment in PHPT patients, the synthesis of procollagen type 1 is temporarily increased with increased osteoblastic population and decreased action of PTH [66,67]. Consistent with this, in our study, P1NP was increased 2 weeks after surgery.

There are several limitations to this study. The miRNAs examined here were related to TH BMD changes but not to LS BMD or FN BMD changes. The number of patients in this study was small owing to the rarity of PHPT. Although PHPT is one of the main causes of secondary osteoporosis, it has an incidence of approximately 80 out of 100,000 (0.08%) in Asians [68]. Despite the small study population, however, the characteristics of the study population were similar to the general characteristics of PHPT, with a ratio of female-to-male of 5:1, and the mean age of 55 years [69]. In addition, the existing markers associated with BMD changes after surgery, such as calcium, CTx, and P1NP [9,41], were also associated with BMD changes in the present study. There was no control group, and miRNAs investigated in the present study were selected by literature review, increasing the chances of false-positive target identification. The mechanisms by which miR-122-5p and miR-375 adversely affect postoperative BMD recovery in PHPT patients are yet to be confirmed by a functional study.

In conclusion, preoperative circulating miR-122-5p and miR-375 levels were negatively associated with TH BMD change after parathyroidectomy in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Our findings suggest that miRNAs have a potential to facilitate individualized treatment of PHPT. This study was a preliminary proof-of-concept study that requires additional validation.

Abbreviations

| AR | androgen receptor |

| IGF1 | insulin like growth factor 1 |

| MAPK1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 |

| THBS1 | thrombospondin 1 |

| ABCB1 | ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 1 |

| IL1B | interleukin 1 beta |

| LRP6 | low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 |

| BMP2K | bone morphogenic proteins (BMP)-2-inducible kinase |

| CALCR | calcitonin receptor |

| CNR1 | cannabinoid receptor 1 |

| ITGA1 | integrin subunit alpha 1 |

| LRP5 | low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 |

| PTK2B | protein tyrosine kinase 2 beta |

| RUNX2 | RUNX family transcription factor 2 |

| STAT1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 |

| VDR | vitamin D receptor |

| ALPL | alkaline phosphatase, biomineralization associated |

| PLOD1 | procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 1 |

| IL1A | interleukin 1 alpha |

| MTHFR | methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase |

| PTHLH | parathyroid hormone like hormone |

| SOST | sclerostin |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| ADM | adrenomedullin |

| CDC73 | cell division cycle 73 |

| MEN1 | menin 1 |

| NOS3 | nitric oxide synthase 3 |

| SDHAF2 | succinate dehydrogenase complex assembly factor 2 |

| ANKH | ANKH inorganic pyrophosphate transport regulator |

| BMP2 | bone morphogenetic protein 2 |

| CD47 | cluster of differentiation 47 molecule |

| CTSK | cathepsin K |

| ESR1 | estrogen receptor 1 |

| ESR2 | estrogen receptor 2 |

| ICAM1 | intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| TGFB1 | transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| PTH | parathyroid hormone |

| IGF1R | insulin like growth factor 1 receptor |

| CA10 | carbonic anhydrase 10 |

| COL1A1 | collagen type I alpha 1 chain |

| FGFBP1 | fibroblast growth factor binding protein 1 |

| IL6 | interleukin 6 |

| VKORC1 | vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 |

| CD44 | cluster of differentiation 44 molecule (Indian blood group) |

| SLC26A6 | solute carrier family 26 member 6 |

| KIT | KIT proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase |

| DKK1 | dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 |

| SPARC | secreted protein acidic and cysteine rich |

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diagnostics11091704/s1, Figure S1: Pearson correlation heatmap of selected osteoporotic fracture-related miRNAs and study covariates. Table S1: The pre-specified panel of selected miRNAs and target genes related to osteoporosis and primary hyperparathyroidism. Table S2: Univariable regression (β coefficient) for the association of log-transformed preoperative miRNAs (−∆Ct) and lumbar spine (LS) and femoral neck (FN) bone mineral density (BMD) percent change from baseline (%), 1 year after parathyroidectomy, in PHPT patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L., N.H. and Y.R.; methodology, S.L., Y.K., S.P. and H.-I.J.; validation, S.L., N.H., Y.K. and Y.R.; investigation, S.L., N.H. and Y.R.; resources, N.H., J.J. and Y.R.; data curation, Y.K., N.H. and Y.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, N.H. and Y.R.; visualization, S.L. and K.-J.K.; supervision, S.P., K.-J.K., J.J. and H.-I.J.; project administration, Y.R.; funding acquisition, Y.R. and N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Severance Hospital Referral Fund for Clinical Excellence (SHRC C-2019-0032).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital (IRB no. 4-2019-1067).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Y. Rhee has served as a consultant for Amgen and has received honorarium from Amgen. The other authors have no relevant disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bours S.P.G., van Geel T.A.C.M., Geusens P.P.M.M., Janssen M.J.W., Janzing H.M.J., Hoffland G.A., Willems P.C., van den Bergh J.P.W. Contributors to secondary osteoporosis and metabolic bone diseases in patients presenting with a clinical fracture. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96:1360–1367. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilczek M.L., Kälvesten J., Bergström I., Pernow Y., Sääf M., Freyschuss B., Brismar T.B. Can secondary osteoporosis be identified when screening for osteoporosis with digital x-ray radiogrammetry? Initial results from the stockholm osteoporosis project (stop) Maturitas. 2017;101:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin M.R., Bilezikian J.P., McMahon D.J., Jacobs T., Shane E., Siris E., Udesky J., Silverberg S.J. The natural history of primary hyperparathyroidism with or without parathyroid surgery after 15 years. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;93:3462–3470. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh M.W., Zhou H., Adams A.L., Ituarte P.H., Li N., Liu I.L., Haigh P.I. The relationship of parathyroidectomy and bisphosphonates with fracture risk in primary hyperparathyroidism: An observational study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016;164:715–723. doi: 10.7326/M15-1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma J., Itum D.S., Moss L., Li C., Weber C. Predictors of bone mineral density improvement in patients undergoing parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism. World J. Surg. 2014;38:1268–1273. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2555-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakaoka D., Sugimoto T., Kobayashi T., Yamaguchi T., Kobayashi A., Chihara K. Prediction of bone mass change after parathyroidectomy in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;85:1901–1907. doi: 10.1210/jc.85.5.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nomura R., Sugimoto T., Tsukamoto T., Yamauchi M., Sowa H., Chen Q., Yamaguchi T., Kobayashi A., Chihara K. Marked and sustained increase in bone mineral density after parathyroidectomy in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism; a six-year longitudinal study with or without parathyroidectomy in a japanese population. Clin. Endocrinol. 2004;60:335–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koumakis E., Souberbielle J.C., Payet J., Sarfati E., Borderie D., Kahan A., Cormier C. Individual site-specific bone mineral density gain in normocalcemic primary hyperparathyroidism. Osteoporos. Int. 2014;25:1963–1968. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso S., Ferrero E., Donat M., Martínez G., Vargas C., Hidalgo M., Moreno E. The usefulness of high pre-operative levels of serum type i collagen bone markers for the prediction of changes in bone mineral density after parathyroidectomy. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2012;35:640–644. doi: 10.3275/7923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tay Y.D., Cusano N.E., Rubin M.R., Williams J., Omeragic B., Bilezikian J.P. Trabecular bone score in obese and nonobese subjects with primary hyperparathyroidism before and after parathyroidectomy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018;103:1512–1521. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-02169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sims N.A., Ng K.W. Implications of osteoblast-osteoclast interactions in the management of osteoporosis by antiresorptive agents denosumab and odanacatib. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2014;12:98–106. doi: 10.1007/s11914-014-0196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niederle M.B., Foeger-Samwald U., Riss P., Selberherr A., Scheuba C., Pietschmann P., Niederle B., Kerschan-Schindl K. Effectiveness of anti-osteoporotic treatment after successful parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2019;404:681–691. doi: 10.1007/s00423-019-01815-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vestergaard P., Mollerup C.L., Frøkjaer V.G., Christiansen P.M., Blichert-Toft M., Mosekilde L. Cohort study of fracture risk before and after surgery of primary hyperparathyroidism. Ugeskr. Laeger. 2001;163:4875–4878. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7261.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deiuliis J.A. Micrornas as regulators of metabolic disease: Pathophysiologic significance and emerging role as biomarkers and therapeutics. Int. J. Obes. 2016;40:88–101. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Párrizas M., Novials A. Circulating micrornas as biomarkers for metabolic disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;30:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell P.S., Parkin R.K., Kroh E.M., Fritz B.R., Wyman S.K., Pogosova-Agadjanyan E.L., Peterson A., Noteboom J., O’Briant K.C., Allen A., et al. Circulating micrornas as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y., Yujiao W., Fang W., Linhui Y., Ziqi G., Zhichen W., Zirui W., Shengwang W. The roles of mirna, lncrna and circrna in the development of osteoporosis. Biol. Res. 2020;53:40. doi: 10.1186/s40659-020-00309-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko N.-Y., Chen L.-R., Chen K.-H. The role of micro rna and long-non-coding rna in osteoporosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:4886. doi: 10.3390/ijms21144886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao Y., Patil S., Qian A. The role of micrornas in bone metabolism and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:6081. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciuffi S., Donati S., Marini F., Palmini G., Luzi E., Brandi M.L. Circulating micrornas as novel biomarkers for osteoporosis and fragility fracture risk: Is there a use in assessment risk? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:6927. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pala E., Denkçeken T. Differentially expressed circulating mirnas in postmenopausal osteoporosis: A meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep. 2019;39:BSR20190667. doi: 10.1042/BSR20190667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellavia D., De Luca A., Carina V., Costa V., Raimondi L., Salamanna F., Alessandro R., Fini M., Giavaresi G. Deregulated mirnas in bone health: Epigenetic roles in osteoporosis. Bone. 2019;122:52–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J., Li S., Li L., Li M., Guo C., Yao J., Mi S. Exosome and exosomal microrna: Trafficking, sorting, and function. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015;13:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seeliger C., Karpinski K., Haug A.T., Vester H., Schmitt A., Bauer J.S., van Griensven M. Five freely circulating mirnas and bone tissue mirnas are associated with osteoporotic fractures. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014;29:1718–1728. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verdelli C., Sansoni V., Perego S., Favero V., Vitale J., Terrasi A., Morotti A., Passeri E., Lombardi G., Corbetta S. Circulating fractures-related micrornas distinguish primary hyperparathyroidism-related from estrogen withdrawal-related osteoporosis in postmenopausal osteoporotic women: A pilot study. Bone. 2020;137:115350. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverberg S.J., Shane E., de la Cruz L., Dempster D.W., Feldman F., Seldin D., Jacobs T.P., Siris E.S., Cafferty M., Parisien M.V., et al. Skeletal disease in primary hyperparathyroidism. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1989;4:283–291. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dempster D.W., Müller R., Zhou H., Kohler T., Shane E., Parisien M., Silverberg S.J., Bilezikian J.P. Preserved three-dimensional cancellous bone structure in mild primary hyperparathyroidism. Bone. 2007;41:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dempster D., Parisien M., Silverberg S., Liang X.-G., Schnitzer M., Shen V., Shane E., Kimmel D., Recker R., Lindsay R. On the mechanism of cancellous bone preservation in postmenopausal women with mild primary hyperparathyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999;84:1562–1566. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.5.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gracia-Marco L., García-Fontana B., Ubago-Guisado E., Vlachopoulos D., García-Martín A., Muñoz-Torres M. Analysis of bone impairment by 3d dxa hip measures in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism: A pilot study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020;105:175–184. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cipriani C., Abraham A., Silva B.C., Cusano N.E., Rubin M.R., McMahon D.J., Zhang C., Hans D., Silverberg S.J., Bilezikian J.P. Skeletal changes after restoration of the euparathyroid state in patients with hypoparathyroidism and primary hyperparathyroidism. Endocrine. 2017;55:591–598. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1101-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baim S., Wilson C.R., Lewiecki E.M., Luckey M.M., Downs R.W., Lentle B.C. Precision assessment and radiation safety for dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry: Position paper of the international society for clinical densitometry. J. Clin. Densitom. 2005;8:371–378. doi: 10.1385/JCD:8:4:371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewiecki E.M., Gordon C.M., Baim S., Leonard M.B., Bishop N.J., Bianchi M.L., Kalkwarf H.J., Langman C.B., Plotkin H., Rauch F., et al. International society for clinical densitometry 2007 adult and pediatric official positions. Bone. 2008;43:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.08.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarecki P., Hackl M., Grillari J., Debono M., Eastell R. Serum micrornas as novel biomarkers for osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Bone. 2020;130:115105. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2019.115105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonald J.S., Milosevic D., Reddi H.V., Grebe S.K., Algeciras-Schimnich A. Analysis of circulating microrna: Preanalytical and analytical challenges. Clin. Chem. 2011;57:833–840. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.157198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silver N., Best S., Jiang J., Thein S.L. Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using real-time pcr. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfaffl M.W., Tichopad A., Prgomet C., Neuvians T.P. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: Bestkeeper--excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004;26:509–515. doi: 10.1023/B:BILE.0000019559.84305.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen C.L., Jensen J.L., Ørntoft T.F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-pcr data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5245–5250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandesompele J., De Preter K., Pattyn F., Poppe B., Van Roy N., De Paepe A., Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative rt-pcr data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sticht C., De La Torre C., Parveen A., Gretz N. Mirwalk: An online resource for prediction of microrna binding sites. PLoS ONE. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lumachi F., Camozzi V., Ermani M., DE Lotto F., Luisetto G. Bone mineral density improvement after successful parathyroidectomy in pre- and postmenopausal women with primary hyperparathyroidism: A prospective study. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1117:357–361. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinl G.K., Yeh R., Walker M.D., McManus C., Lee J.A., Kuo J.H. Preoperative imaging predicts change in bone mineral density after parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism. Bone. 2021;145:115871. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2021.115871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiaoling G., Shuaibin L., Kailu L. Microrna-19b-3p promotes cell proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of bmscs by interacting with lncrna h19. BMC Med. Genet. 2020;21:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12881-020-0948-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J., Tu Q., Bonewald L.F., He X., Stein G., Lian J., Chen J. Effects of mir-335-5p in modulating osteogenic differentiation by specifically downregulating wnt antagonist dkk1. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:1953–1963. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li T., Li H., Wang Y., Li T., Fan J., Xiao K., Zhao R.C., Weng X. Microrna-23a inhibits osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by targeting lrp5. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016;72:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hassan M.Q., Gordon J.A., Beloti M.M., Croce C.M., Van Wijnen A.J., Stein J.L., Stein G.S., Lian J.B. A network connecting runx2, satb2, and the mir-23a∼ 27a∼ 24-2 cluster regulates the osteoblast differentiation program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:19879–19884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007698107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeng Y., Qu X., Li H., Huang S., Wang S., Xu Q., Lin R., Han Q., Li J., Zhao R.C. Microrna-100 regulates osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells by targeting bmpr2. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2375–2381. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mizuno Y., Yagi K., Tokuzawa Y., Kanesaki-Yatsuka Y., Suda T., Katagiri T., Fukuda T., Maruyama M., Okuda A., Amemiya T. Mir-125b inhibits osteoblastic differentiation by down-regulation of cell proliferation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;368:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fan Q., Li Y., Sun Q., Jia Y., He C., Sun T. Mir-532-3p inhibits osteogenic differentiation in mc3t3-e1 cells by downregulating ets1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;525:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.02.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee Y., Kim H.J., Park C.K., Kim Y.-G., Lee H.-J., Kim J.-Y., Kim H.-H. Microrna-124 regulates osteoclast differentiation. Bone. 2013;56:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qadir A.S., Um S., Lee H., Baek K., Seo B.M., Lee G., Kim G.-S., Woo K.M., Ryoo H.-M., Baek J.-H. Mir-124 negatively regulates osteogenic differentiation and in vivo bone formation of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015;116:730–742. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheng P., Chen C., He H.B., Hu R., Zhou H.D., Xie H., Zhu W., Dai R.C., Wu X.P., Liao E.Y. Mir-148a regulates osteoclastogenesis by targeting v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog b. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013;28:1180–1190. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tian L., Zheng F., Li Z., Wang H., Yuan H., Zhang X., Ma Z., Li X., Gao X., Wang B. Mir-148a-3p regulates adipocyte and osteoblast differentiation by targeting lysine-specific demethylase 6b. Gene. 2017;627:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feng L., Xia B., Tian B.-F., Lu G.-B. Mir-152 influences osteoporosis through regulation of osteoblast differentiation by targeting rictor. Pharm. Biol. 2019;57:586–594. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2019.1657153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Panach L., Mifsut D., Tarín J.J., Cano A., García-Pérez M. Serum circulating micrornas as biomarkers of osteoporotic fracture. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2015;97:495–505. doi: 10.1007/s00223-015-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang C., He H., Wang L., Jiang Y., Xu Y. Reduced mir-144-3p expression in serum and bone mediates osteoporosis pathogenesis by targeting rank. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2018;96:627–635. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2017-0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mandourah A.Y., Ranganath L., Barraclough R., Vinjamuri S., Hof R.V., Hamill S., Czanner G., Dera A.A., Wang D., Barraclough D.L. Circulating micrornas as potential diagnostic biomarkers for osteoporosis. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:8421. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26525-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kerschan-Schindl K., Hackl M., Boschitsch E., Föger-Samwald U., Nägele O., Skalicky S., Weigl M., Grillari J., Pietschmann P. Diagnostic performance of a panel of mirnas (osteomir) for osteoporosis in a cohort of postmenopausal women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2021;108:725–737. doi: 10.1007/s00223-020-00802-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Komori T. Osteoimmunology. Springer; Boston, MA, USA: 2009. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by runx2; pp. 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Du F., Wu H., Zhou Z., Liu Y.U. Microrna-375 inhibits osteogenic differentiation by targeting runt-related transcription factor 2. Exp. Med. 2015;10:207–212. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun T., Li C.T., Xiong L., Ning Z., Leung F., Peng S., Lu W.W. Mir-375-3p negatively regulates osteogenesis by targeting and decreasing the expression levels of lrp5 and β-catenin. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0171281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meng Y.C., Lin T., Jiang H., Zhang Z., Shu L., Yin J., Ma X., Wang C., Gao R., Zhou X.H. Mir-122 exerts inhibitory effects on osteoblast proliferation/differentiation in osteoporosis by activating the pcp4-mediated jnk pathway. Mol. Nucleic Acids. 2020;20:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liao W., Ning Y., Xu H.J., Zou W.Z., Hu J., Liu X.Z., Yang Y., Li Z.H. Bmsc-derived exosomes carrying microrna-122-5p promote proliferation of osteoblasts in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin. Sci. 2019;133:1955–1975. doi: 10.1042/CS20181064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garnero P., Ferreras M., Karsdal M., Nicamhlaoibh R., Risteli J., Borel O., Qvist P., Delmas P., Foged N., Delaissé J. The type i collagen fragments ictp and ctx reveal distinct enzymatic pathways of bone collagen degradation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2003;18:859–867. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kelch S., Balmayor E.R., Seeliger C., Vester H., Kirschke J.S., van Griensven M. Mirnas in bone tissue correlate to bone mineral density and circulating mirnas are gender independent in osteoporotic patients. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:15861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16113-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xin Y., Liu Y., Liu D., Li J., Zhang C., Wang Y., Zheng S. New function of runx2 in regulating osteoclast differentiation via the akt/nfatc1/ctsk axis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2020;106:553–566. doi: 10.1007/s00223-020-00666-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coen G., Mazzaferro S., De Antoni E., Chicca S., DiSanza P., Onorato L., Spurio A., Sardella D., Trombetta M., Manni M., et al. Procollagen type 1 c-terminal extension peptide serum levels following parathyroidectomy in hyperparathyroid patients. Am. J. Nephrol. 1994;14:106–112. doi: 10.1159/000168698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo C.Y., Holland P.A., Jackson B.F., Hannon R.A., Rogers A., Harrison B.J., Eastell R. Immediate changes in biochemical markers of bone turnover and circulating interleukin-6 after parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2000;142:451–459. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1420451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yeh M.W., Ituarte P.H.G., Zhou H.C., Nishimoto S., Amy Liu I.-L., Harari A., Haigh P.I., Adams A.L. Incidence and prevalence of primary hyperparathyroidism in a racially mixed population. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:1122–1129. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bilezikian J.P., Cusano N.E., Khan A.A., Liu J.-M., Marcocci C., Bandeira F. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016;2:16033. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.