ABSTRACT

The need to prioritise those furthest behind is well understood in global health circles, and how human rights norms and standards can help often touted. As rights concerns are particularly recognised in sexual and reproductive health (SRH) programming, as part of a larger exercise, a review was conducted to identify documented barriers and facilitators to implementation. Given the role global guidance plays in implementing rights-based approaches to SRH, UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) guidelines, tools, recommendations and guidance that include the explicit mention of human rights principles served as the basis for this exercise. This was followed by an extensive review of the literature. Sources reviewed confirmed barriers include not only broad structural, policy and health systems barriers but financial, staffing and time constraints, as well as lack of understanding of concretely how to include human rights in these efforts. Facilitators include the existence of human rights champions, leadership, strong civil society participation, training, and funding made available specifically for implementation. Investment in indicators and documentation sensitive to human rights is warranted in sexual and reproductive health, as well as other health topics, to best serve populations who need them most.

KEYWORDS: Implementation, sexual health, reproductive health, human rights, health and human rights

Background

The importance of ensuring human rights in public health efforts is often touted, and importantly has also been demonstrated in practice. Attention to human rights has been documented to increase access and use of health services (Bustreo & Hunt, 2013), while poor health outcomes have been linked to neglect or violation of human rights (Hartmann et al., 2016). Global standards continue to show support for promoting universal access through the incorporation of human rights principles in order to improve health outcomes. It has long been recognised that a rights-based approach to health necessitates prioritising those who are the furthest behind in health policy and programming initiatives. In the context of the 2030 Agenda and the maxim of ‘leaving no one behind’, the integration of human rights principles into normative global health standards and guidance is generally recognised to be an essential step to ensure all people achieve the highest attainable standard of health (High-Level Working Group on the Health and Human Rights of Women, Children and Adolescents, 2017; UNDP, 2012).

At the level of implementation, interest is growing if not yet universal. Across the range of health topics where efforts have been made, sexual and reproductive health appears to be an area where there is fairly strong consensus that rights offer an added value. However, when the desire, to concretely implement and monitor human rights principles in sexual and reproductive health interventions, exists, it appears nonetheless there is limited guidance on how to effectively do this, what is there is not well utilised, common barriers and facilitators to implementation are not well documented, and there is limited agreement on the measures needed to determine effectiveness. The World Health Organization (WHO) is a key agency responsible for the creation and dissemination of global public health standards and guidance. Resources generated often take the form of guidelines, tools, recommendations, and guidance, including clinical guides, policy and programmatic guidance, monitoring and evaluation materials, and training materials across a range of health topics. Within the United Nations system, the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP) leads the work surrounding sexual and reproductive health (SRH) (WHO, 2020a).

While a number of studies have assessed the quality and use of various WHO guidance documents, to our knowledge, an assessment of the inclusion of human rights in the SRH-related guidance produced, and any related barriers or facilitators to implementation have not yet been published (Alexander et al., 2014; Burda et al., 2014; Sinclair et al., 2013).

As a first step, to better understand the ability of the global health community to truly integrate human rights norms and standards into SRH programming initiatives, this study began by systematically assessing the inclusion of key human rights principles in WHO HRP guidelines, tools, recommendations, and guidance including clinical guides, policy and programmatic guidance, monitoring and evaluation materials and training materials (hereinafter called ‘guidance documents’). A review of the literature followed, to determine if, even when guidance exists, there are barriers to its implementation, as well as what lessons can be derived from common facilitators. Using WHO’s own guidance on human rights in the context of SRH, our review encompassed the nine human rights principles widely understood by HRP and its partners to comprise a rights-based approach to sexual and reproductive health, including accessibility, availability, acceptability, quality of care, non-discrimination, privacy and confidentiality, informed decision-making, accountability and participation (WHO, 2014). When necessary, and as described below, to facilitate analysis, we focused primarily on the ‘backbone’ of a rights-based approach, the more widely used rights principles of participation, non-discrimination and accountability (WHO, 2017).

The identified WHO documents and literature review were then used to support the analysis and discussion that follow. The work presented here serves as a first step within a larger investigation of barriers and facilitators, including key informant interviews, in an effort to understand how rights integration in SRH work can best be taken forward.

Methods

This section describes the methodology used in the WHO document review, and the literature review that followed.

WHO HRP and RHL document review

In July-August 2019, 814 documents, from the ‘guidelines’, ‘clinical guides’, ‘policy and programmatic guidance’, ‘training materials’, ‘monitoring and evaluation’, ‘publications’ and ‘advocacy’ sections of the WHO HRP website, were assessed for relevance using the below inclusion criteria (WHO, 2020b). In some cases, duplicates were found across the aforementioned sections. The contents of the Reproductive Health Library (RHL) website were also reviewed, even as no additional documents were identified for inclusion (WHO, 2019).

Inclusion criteria

Title or executive summary explicitly states the document is a WHO HRP guideline, tool, recommendation, or guidance document

Available on the WHO HRP website or RHL

Explicit reference to at least one of the following human rights search words: ‘human rights’ OR ‘human rights-based approach’ OR ‘availability’ OR ‘accessibility’ OR ‘acceptability’ OR ‘quality’ OR ‘3AQ’ OR ‘accountability’ OR ‘non-discrimination’ OR ‘privacy’ OR ‘confidentiality’ OR ‘informed decision-making’ OR ‘participation’ OR ‘duty bearer’ OR ‘rights-holders’

Published between January 2010 and August 2019

Available in English

Only documents published after January 2010 were included in this study because it was determined by the authors that guidance moves quickly, and a 10-year time span was appropriate to understand the materials most relied on for implementation of SRHR intervention.

After an initial review of the documents, meeting the above inclusion criteria, was made, a secondary review was conducted using search words chosen because they are the backbone of a rights-based approach (RBA): ‘non-discrimination’, ‘participation’, ‘accountability’ (UN, 2003). Documents that contained these terms were then independently assessed by two reviewers for contextual use to ensure alignment with established definitions in relation to health (Gruskin et al., 2012). Any discrepancy identified was resolved by a senior member of the study team and documents that contained the refined search words, but where usage did not align with established human rights criteria were excluded.

Literature review

Building on the findings of the WHO document review, a literature review of English-language peer-reviewed literature from January 2010 to August 2019 was conducted using PubMed and Scopus. To determine any barriers to implementation, the search words used were: the exact wording of the title of WHO document AND ‘implementation’ AND ‘barriers’ OR ‘lessons learned’ OR ‘challenges’. The search words used to identify articles discussing facilitators for implementation for each of the rights explicit WHO documents were: the exact wording of the title of WHO document AND ‘implementation’ AND ‘facilitators’ OR ‘enablers’ OR ‘drivers’. Search results were then assessed for relevance using the below inclusion criteria. All search results potentially meeting inclusion criteria were reviewed by a senior member of the research team for final inclusion determination.

Inclusion criteria

WHO HRP document implementation explicitly described

Barriers or facilitators to implementation described

Rights concepts mentioned

Available in English

Analysis

Articles identified to meet inclusion criteria went through further analysis to determine how rights principles were discussed, with specific attention to non-discrimination, availability, accessibility, acceptability, quality, informed decision-making, privacy and confidentiality, participation and accountability. For each article, the noted barriers or facilitators to implementation were extracted, with attention to whether they explicitly or implicitly addressed human rights concerns. These data are included in the results (Table 1).

Table 1. Literature review results: barriers and facilitators to the implementation of rights sensitive SRH interventions.

| Peer-reviewed article | WHO document cited | Implementation barriers | Implementation facilitators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural and health systems barriers | Rights-explicit barriers | Structural and health systems facilitators | Rights-explicit facilitators | ||

| Cordero, J. P., Steyn, P. S., Gichangi, P., Kriel, Y., Milford, C., Munakampe, M., Njau, I., Nkole, T., Silumbwe, A., Smit, J., & Kiarie, J. (2019). Community and Provider Perspectives on Addressing Unmet Need for Contraception: Key Findings from a Formative Phase Research in Kenya, South Africa and Zambia (2015–2016). African Journal of Reproductive Health, 23(3), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2019/v23i3.10 | World Health Organization. (2014). Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services: Guidance and recommendations. |

|

|

|

|

| Crankshaw, T. L., Kriel, Y., Milford, C., Cordero, J. P., Mosery, N., Steyn, P. S., & Smit, J. (2019). As we have gathered with a common problem, so we seek a solution’: exploring the dynamics of a community dialogue process to encourage community participation in family planning/contraceptive programmes. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 710. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4490-6 | World Health Organization. (2014). Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services: Guidance and recommendations. |

|

|

|

|

| Dennis, M. L., Owolabi, O. O., Cresswell, J. A., Chelwa, N., Colombini, M., Vwalika, B., Mbizvo, M. T., & Campbell, O. (2019). A new approach to assess the capability of health facilities to provide clinical care for sexual violence against women: a pilot study. Health Policy and Planning, 34(2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy106 | World Health Organization. (2017). Responding to children and adolescents who have been sexually abused: WHO Guidelines. |

|

|

|

|

| Abuya, T., Sripad, P., Ritter, J., Ndwiga, C., & Warren, C. E. (2018). Measuring mistreatment of women throughout the birthing process: implications for quality of care assessments. Reproductive Health Matters, 26(53), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2018.1502018 | World Health Organization. (2016). Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. |

|

|

|

|

| Kraft, J. M., Oduyebo, T., Jatlaoui, T. C., Curtis, K. M., Whiteman, M. K., Zapata, L. B., & Gaffield, M. E. (2018). Dissemination and use of WHO family planning guidance and tools: a qualitative assessment. Health Research Policy and Systems, 16(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0321-1 | World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, & South African Medical Research Council. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. |

|

|

||

| Manu, A., Arifeen, S., Williams, J., Mwasanya, E., Zaka, N., Plowman, B. A., Jackson, D., Wobil, P., & Dickson, K. (2018). Assessment of facility readiness for implementing the WHO/UNICEF standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities – experiences from UNICEF’s implementation in three countries of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 531. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3334-0 | World Health Organization. (2016). Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. |

|

|

|

|

| Tran, N. T., Harker, K., Yameogo, W., Kouanda, S., Millogo, T., Menna, E. D., Lohani, J. R., Maharjan, O., Beda, S. J., Odinga, E. A., Ouattara, A., Ouedraogo, C., Greer, A., & Krause, S. (2017). Clinical outreach refresher trainings in crisis settings (S-CORT): clinical management of sexual violence survivors and manual vacuum aspiration in Burkina Faso, Nepal, and South Sudan. Reproductive Health Matters, 25(51), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1405678 | World Health Organization. (2012). Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. |

|

|

||

| Hoopes, A. J., Chandra-Mouli, V., Steyn, P., Shilubane, T., & Pleaner, M. (2015). An Analysis of Adolescent Content in South Africa’s Contraception Policy Using a Human Rights Framework. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 57(6), 617–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.08.012 | World Health Organization. (2014). Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services: Guidance and recommendations. |

|

|

|

|

| Samandari, G., Wolf, M., Basnett, I., Hyman, A., & Andersen, K. (2012). Implementation of legal abortion in Nepal: a model for rapid scale-up of high-quality care. Reproductive Health, 9, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-47559-7 | World Health Organization. (2012). Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. |

|

|

|

|

Results

The review of WHO documents was the first step leading towards an in-depth review of the relevant peer-reviewed literature to identify the barriers and facilitators for implementation of rights in related SRH programming. The literature review took as its focus implementation of rights-based WHO standards in order to ensure concrete linkages between the results of the two searches. These results are presented below.

WHO HRP and RHL document review?

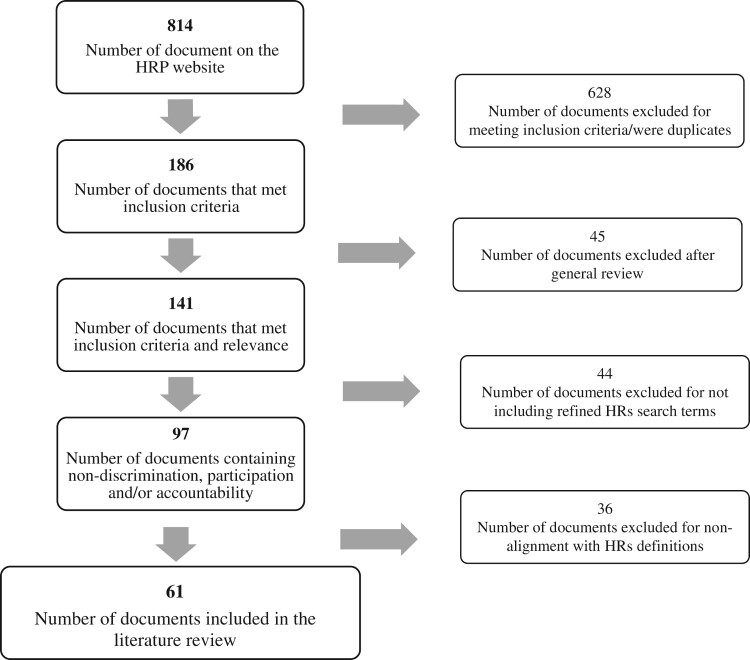

Of the 814 documents reviewed, 628 did not meet the inclusion criteria noted above or were duplicates leaving 186 documents for further review. Of those, 45 documents were excluded after further general review because they were clinical leaving 141 for further analysis. Of these, 97 included at least one of the refined human rights search words. Upon contextual review, 61 documents were ultimately determined to be relevant to this exercise. These are listed in Appendix 1. Figure 1 describes this process which ultimately informed the literature review determining barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Figure 1.

Document assessment flow diagram.

As noted above, the 61 identified WHO documents laid the foundation for the subsequent literature review.

Literature review: Barriers and facilitators to implementation

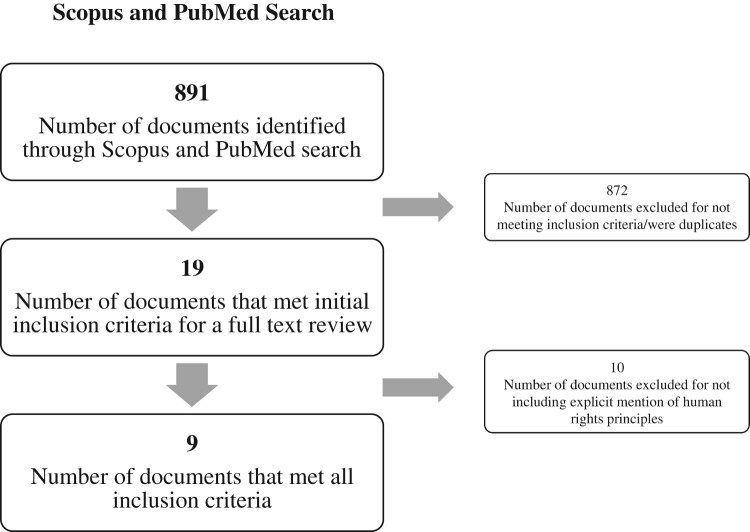

Using Scopus and PubMed, 891 article abstracts were reviewed. Of those, only 19 were identified as potentially meeting inclusion criteria. After a full text review, only nine of these 19 met full inclusion criteria by including mention of a WHO document; articulation of rights principles and discussion of barriers and/or facilitators for implementation. Figure 2 outlines the search results and process for article inclusion and exclusion.

Figure 2.

Search results flow diagram for Scopus and PubMed.

Interestingly, only 41 of the 61 identified WHO documents were mentioned in the range of articles found through the Scopus and PubMed search. And, only five of these WHO documents were referenced in the nine articles ultimately meeting inclusion criteria (see Appendix 2).

It is worth noting here that the mention of rights and rights concerns in the literature and materials reviewed happens in two distinct ways, explicitly but also implicitly. An explicit mention specifically names a human rights principle. Conversely, an implicit mention potentially measures an aspect of human rights, even if rights are not explicitly addressed and, as used here, bring to light overall structural and health systems aspects that implicitly raise rights concerns that can either constrain or support implementation. To reflect this, the barriers and facilitators identified in each of the nine articles were divided into two themes: structural and health systems concerns with more implicit attention to rights, and those that were more rights-explicit in their presentation. In Table 1, within each category, the most generic barriers and facilitators are presented first followed by those that are more context specific. Presented in reverse chronological order, Table 1 summarises published barriers and facilitators to implementation of SRH interventions.

The information above reveals a host of issues that can constrain or facilitate implementation of rights sensitive SRH interventions.

Implementation barriers

Broad structural barriers to implementation range from inadequate legal and policy frameworks to infrastructure, health system, training and other constraints. As shown in Table 1, with respect to policy constraints, these include not only policy directly in opposition to rights-affirming care such as the United States Helms Amendment that prevents acquisition of adequate supplies for abortion services (Samandari et al., 2012), but policies, such as those promoting access for key populations particularly adolescent populations, that may exist at a rhetorical level but are not effectively implemented or well known. Lack of political will to address rights issues or lack of interest in rights principles as a mechanism to enhance policy can also constrain effectiveness, even when an adequate policy framework exists. As shown in Table 1, for example, lack of political will to invest in family planning and contraception in Kenya, South Africa and Zambia was a barrier to adequate implementation, resulting in limited improvement in patient provider relationships relevant to informed decision-making and a shortage of commodities for contraception, even as, in the first instance, financial constraints in resource-limited settings contribute to an inability to provide initial investments in these and other programmes and services (Cordero et al., 2019). With respect to health systems constraints, particularly in resource-limited settings, even with good will, multiple under-funded priorities exist, making it impossible to do many things that are needed and required (Hoopes et al., 2015; Manu et al., 2018; Samandari et al., 2012). There is also concern by some that implementation of these sorts of human rights-related interventions will be time-consuming and costly (Manu et al., 2018; Samandari et al., 2012). Coupled with personnel shortages, high workloads and lack of adequate training or equipment (Abuya et al., 2018; Cordero et al., 2019; Dennis et al., 2019; Hoopes et al., 2015; Kraft et al., 2018; Manu et al., 2018; Samandari et al., 2012; Tran et al., 2017), sexual and reproductive health in and of itself is often not prioritised (Cordero et al., 2019). Finally, there is concern that the health care facilities used to pilot test rights-sensitive SRH interventions are those most capable and structurally ready, preventing a thorough picture of how to go about implementing in most settings (Manu et al., 2018).

Rights explicit barriers include a general lack of knowledge as to how best to ensure or monitor the participation of either health care workers or the local community in SRH interventions, and this concern is particularly salient when there is already a lack of trust and understanding between health care workers and the local community (Cordero et al., 2019; Hoopes et al., 2015; Samandari et al., 2012). Stigma and discrimination among health care workers, towards women and, in particular, as concerns their use of SRH services such as family planning, contraceptives, and abortion, remains a huge barrier (Cordero et al., 2019; Samandari et al., 2012). As noted in Table 1, underlying power differentials between providers and clients, including differences with respect to age, gender and professional status can prevent trust and consequently present additional barriers to implementation even of those programmes that do exist (Crankshaw et al., 2019), with particular issues of concern for the provision of rights-sensitive adolescent SRH services (Hoopes et al., 2015).

Implementation facilitators

In addition to addressing many of the barriers noted above, some additional facilitators for successful implementation came to light through this review. These include the need for strong leadership from government and relevant decision-makers, as well as the capacity and commitment of the institution and the people who work there to take on this sort of work (Samandari et al., 2012). In the example of Nepal, strong governmental ownership led to the creation of a task force and other mechanisms, all of which helped to engage multiple organisations which ultimately assisted in and facilitated implementation (Samandari et al., 2012). Adequate external funding was also key, including supporting oversight and monitoring of these types of activities. Likewise, drawing from another example from Table 1, despite resource constraints, the existence of rights-based family planning guidelines from WHO was important precisely because there is trust that because they come from the WHO that what is there is evidence based, and adaptable to country contexts, which can, in turn, facilitate the political will to implement (Kraft et al., 2018). Rights-based training and capacity-building with appropriate tools and methodologies are clearly of prime importance. Additionally, and particularly relevant here, confidence in WHO and WHO’s provision of evidence-based information appears, at least in the one instance when it was asked directly, to be a key facilitator in uptake of these rights-explicit SRH interventions (Kraft et al., 2018; Tran et al., 2017).

The increase in global attention to the need for respectful care, particularly in maternity services, through the incorporation of human rights principles appears to have been an important facilitator for generating political will even at the most local level (Abuya et al., 2018). At the level of implementation, additional rights’ explicit facilitators include efforts towards broad stakeholder engagement, such as facilitated open dialogue among community members and stakeholders (Crankshaw et al., 2019). These sorts of efforts towards participation are seen as key facilitators able to transcend potential barriers relating to socioeconomic status, age, gender and occupation when implemented in practice (Crankshaw et al., 2019).

Discussion

Taking into consideration the barriers and facilitators described above, it is clear that an enabling legal environment is crucial for successful implementation of rights-attentive sexual and reproductive health services. Structural and health systems facilitators, including adequate financing, training, supplies, staff, facilities and leadership, are needed. Additionally, addressing stigma and discrimination within facilities, ensuring the participation of affected communities through open dialogue, and robust monitoring systems and methods of accountability are all part of supporting successful implementation. To address identified barriers and facilitators requires explicit engagement with rights principles whether with respect to the larger environment where the service is taking place, the facility where the service is being provided, or the community being served. This means, at a minimum, directly operationalising participation, non-discrimination and accountability in all aspects of these interventions. All are critical. When rights are not addressed in one area, barriers can be created even if some identified facilitators are being addressed in another area. Collective attention, for example among global development organisations, government actors, service providers and communities, can help to ensure each of these rights aspects is taken into account to provide a path for success, ultimately eliminating barriers and ensuring programmes and research truly ‘leave no one behind’. Alongside this overall required attention to structures, systems and rights, context nonetheless matters: taking economic, social, cultural, political and other such factors into consideration is not only crucial for rights to be realised but part of what a rights-based approach requires, and necessary for successful implementation.

Despite a wide support for utilising rights principles as a way to improve sexual and reproductive health outcomes, this review highlights the paucity of peer-reviewed evidence, at least in the context of WHO guidance documents, for how to do this in practice. Evidence exists of the difference paying attention to rights makes for health outcomes and access and use of health services. With this in mind, research and evaluation that captures the ‘how’ of what it means to implement human rights in these sorts of interventions has long been called for (Bustreo & Hunt, 2013, Human Rights Council, 2012). The limited literature found on facilitators and barriers to implementation indicates more is needed to understand what works in moving rights from guidelines to utilisation, with particular attention to regional, national and sub-national differences. This review has as its focus WHO guidance in the area of sexual and reproductive health and rights, and therefore may not fully capture what is known about implementation of rights-based approaches to SRH-related issues stemming from other global guidance, such as what has been produced by UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNDP or OHCHR. That said, the lessons captured here would seem to be generalisable to these efforts as well (Human Rights Council, 2012; OHCHR, 2012, 2014, 2015; UNDP, 2012; UNFPA, 2010). In particular, the trust that exists in the materials produced by these organisations, including methodologies for implementing the backbone principles of a rights-based approach (RBA): ‘non-discrimination’, ‘participation’, ‘accountability’.

While human rights principles have been extensively written about and promoted through guidance and standard setting, by WHO amongst others, there is a clear need to help people trying to implement this work by providing additional guidance, tools and methodologies, as well as a need for agreement on the sorts of indicators that can be used to show what was done and how. Across the literature reviewed, researchers expressed the need for assistance in determining clear indicators to help them ensure adequate incorporation of rights in their work, and to measure the relative success of having done so. With important lessons for the translation of global guidance more generally, resources and tools are needed that outline indicators for the implementation of rights principles based on the past successes, helping to better align these guidelines with their use in practice.

The findings from this study suggest the need to optimise the collaboration between those who work to clarify the practical value of human rights for SRH work, those who develop global health resources, and those who implement these interventions. In addition to the limited number of tools to help implementers apply global guidance in practice, what appears to be categorically missing are the resources or outlets that systematically document what works, and what doesn’t, when such efforts are happening on the ground. Findings suggest implementers have not sufficiently documented the approaches used as well as the strengths and limitations of inclusion of human rights principles in their SRH policy and programming initiatives in peer-reviewed journals. An emphasis on publishing implementation findings is critical to help strategically leverage efforts, better inform the types of global guidance resources developed and maximise learning. Importantly, it would also help to strengthen the evidence base so often needed to support and substantiate the scale up of effective rights-based health policy and programming initiatives in SRH and beyond. Efforts must be made not only to support those committed to the production of such guidance or their implementation, but also to ensure rigorous and replicable methods for evaluation, and importantly the involvement of journal editors to secure their engagement in the importance of publishing this work.

Limitations

The scope of this study was limited to a review of guidelines, tools, recommendations and guidance documents from HRP only, which were explicit in their use of human rights and a corresponding literature review. Other departments and programmes across WHO, as well as other technical agencies inside and outside the UN system, may be including human rights in their guidance in other ways, and these may be getting effectively implemented and documented in the literature. This information would not be captured in the present study. The results are, therefore, not necessarily representative of all that exists or is known about implementation which take human rights into account in delivering SRH programmes and services.

Another potential limitation of this study is that the results of the literature review only include PubMed and Scopus search engines and do not include grey literature. It is possible that other relevant implementation experiences are documented through evaluations or other means not captured in this review.

This review as designed has as its focus improving the guidance, and follow-through, that WHO can provide to better implement rights in sexual and reproductive health research and programming. As noted previously, this study is part of a larger investigation that will include interviews with key informants to better understand what is needed to improve rights implementation in practice.

Conclusions

Optimising communication, across the global health community through the sharing of best practices and lessons learned about how best to integrate rights into health programming initiatives, has the potential to improve the relevance and uptake of those global guidance resources that do exist and reduce the barriers faced by implementers. This is particularly important to ensuring human rights norms and standards can be operationalised and moved from rhetorical pronouncements to standard practice in sexual and reproductive health interventions, and of course, ultimately in all areas of health.

The number of WHO guidance documents, we found which seek to be explicit in their use of human rights in SRH work, is smaller than one would imagine, and there are limited documented examples of what works even with respect to the few that do exist. In the context of global efforts towards achieving universal health coverage, the 2030 Agenda, and the maxim of ‘leaving no one behind’, the lack of rights integration in relevant WHO guidance seems like a missed opportunity. Investment in further development of clear and effective indicators, as well as documentation and publication of what is done with WHO and other global guidance is warranted, not simply to take stock of the relevance and effectiveness of global guidance in the SRH area and to identify where additional guidance and support might be useful, but to explicitly take human rights into account in serving the populations who need them most.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Skylar Cummings, Alexandra Endara, Krishni Satchi and Susana Soto Tirado for their support and research assistance in the document and literature reviews.

Appendices.

Appendix 1

Rights explicit documents included in the literature review:

[1] World Health Organization. (2010). Addressing violence against women and HIV/AIDS: What works?. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44378/9789241599863_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[2] World Health Organization. (2017). A guide to identifying and documenting best practices in family planning programmes. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254748/9789290233534-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[3] World Health Organization. (2019). Appropriate storage and management of oxytocin – A key commodity for maternal health. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311524/WHO-RHR-19.5-eng.pdf?ua=1

[4] World Health Organization. (2016). A tool for strengthening gender-sensitive national HIV and Sexual and Reproductive Health (SRH) monitoring and evaluation systems. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/251903/9789241510370-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[5] World Health Organization. (2018). Care of girls & women living with female gential mutilation a clinical handbook. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272429/9789241513913-eng.pdf?ua=1

[6] World Health Organization. (2014). Clinical practice handbook for safe abortion. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/97415/9789241548717_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[7] World Health Organization. (2016). Companion of choice during labour and childbirth for improved quality of care Evidence-to-action brief. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250274/WHO-RHR-16.10-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[8] World Health Organization. (2014). Comprehensive cervical cancer control: A guide to essential practice. 2nd ed. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/144785/9789241548953_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[9] World Health Organization. (2011). Consolidated guideline on sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254885/9789241549998-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[10] World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research (WHO/RHR), & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP), Knowledge for Health Project. (2018). Family planning: A global handbook for providers. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260156/9780999203705-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[11] World Health Organization. (2010). Developing sexual health programmes A framework for action. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70501/WHO_RHR_HRP_10.22_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[12] World Health Organization. (2014). Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/112848/9789241507325_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[13] World Health Organization. (2018). Eliminating virginity testing: an interagency statement. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275451/WHO-RHR-18.15-eng.pdf?ua=

[14] World Health Organization. (2014). Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services Guidance and recommendations. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/102539/9789241506748_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[15] World Health Organization. (2014). Ensuring human rights within contraceptive programmes: A human rights analysis of existing quantitative indicators. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/126799/9789241507493_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[16] World Health Organization. (2015). Ensuring human rights within contraceptive service delivery: implementation guide. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/158866/9789241549103_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[17] World Health Organization. (2014). Framework for ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/133327/9789241507745_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[18] World Health Organization. (2018). Gender-Based Violence Quality Assurance Tool. http://resources.jhpiego.org/system/files/resources/GBV-Quality-Assurance-Tool–EN.pdf

[19] World Health Organization. (2012). Global action plan to control the spread and impact of antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44863/9789241503501_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[20] World Health Organization. (2017). Global guidance on criteria and processes for validation: elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis, 2nd edition. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259517/9789241513272-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[21] World Health Organization. (2016). Global Health Sector Strategy on Sexually Transmitted Infections 2016–2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246296/WHO-RHR-16.09-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[22] World Health Organization. (2016). Global Plan of Action: Health systems address violence against women and girls. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/251664/WHO-RHR-16.13-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[23] World Health Organization. (2016). Global plan of action to strengthen the role of the health system within a national multisectoral response to address interpersonal violence, in particular against women and girls, and against children. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/252276/9789241511537-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[24] World Health Organization. (2018). Guidance on ethical considerations in planning and reviewing research studies on sexual and reproductive health in adolescents. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/273792/9789241508414-eng.pdf?ua=1

[25] World Health Organization. (2014). Health care for women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/136101/WHO_RHR_14.26_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[26] World Health Organization. (2017). Hormonal contraceptive eligibility for women at high risk of HIV Guidance Statement. https://extranet.who.int/iris/restricted/password-login

[27] World Health Organization. (2014). Hormonal contraceptive methods for women at high risk of HIV and living with HIV Guidance Statement. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128537/WHO_RHR_14.24_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[28] World Health Organization. (2019). Improving data for decision-making: a toolkit for cervical cancer prevention and control programmes. https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/data-toolkit-for-cervical-cancer-prevention-control/en/

[29] World Health Organization, & International Telecommunication Union. (2017). Be He@lthy, Be Mobile: A handbook on how to implement mCervicalCancer. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274578/9789241513135-eng.pdf?ua=1

[30] World Health Organization. (2012). Investment case for eliminating mother-to-child transmission of syphilis. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75480/9789241504348_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

[31] World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, & South African Medical Research Council. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

[32] World Health Organization. (2016). Making every baby count: Audit and review of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/249523/9789241511223-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[33] World Health Organization. (2018). Medical management of abortion. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/278968/9789241550406-eng.pdf?ua=1.

[34] World Health Organization. (2011). Methods for surveillance and monitoring of Congenital syphilis elimination within existing systems. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44790/9789241503020_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

[35] World Health Organization. (2017). Monitoring human rights in contraceptive services and programmes. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259274/9789241513036-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

[36] World Health Organization. (2011). Preventing gender-biased sex selection. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44577/9789241501460_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[37] World Health Organization. (2012). Preventing HIV and unintended pregnancies: strategic framework 2011-2015. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/linkages/HIV_and_unintended_pregnancies_SF_2011_2015.pdf

[38] World Health Organization. (2017). Programme reporting standards for sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258932/WHO-MCA-17.11-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[39] World Health Organization. (2017). Quality of care in contraceptive information and services, based on human rights standards: A checklist for health care providers. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254826/9789241512091-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[40] World Health Organization. (2014). Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health and human rights: A toolbox for examining laws, regulations and policies. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/126383/9789241507424_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[41] World Health Organization. (2017). Responding to children and adolescents who have been sexually abused WHO clinical guidelines. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259270/9789241550147-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[42] World Health Organization. (2012). Safe abortion: Technical and policy guidance for health systems. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/97415/9789241548717_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[43] World Health Organization. (2017). Sexual health and its linkages to reproductive health: An operational approach. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258738/9789241512886-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[44] World Health Organization. (2010). Social determinants of sexual and reproductive health. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44344/9789241599528_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[45] World Health Organization. (2012). Social science methods for research on sexual and reproductive health. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44805/9789241503112_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[46] World Health Organization. (2016). Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/249155/9789241511216-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[47] World Health Organization. (2015). Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/153544/9789241508483_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[48] World Health Organization. (2017). Strengthening health systems to respond to women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence: A manual for health managers. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259489/9789241513005-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[49] World Health Organization. (2010). The sexual and reproductive health of young adolescents in developing countries. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70569/WHO_RHR_11.11_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[50] World Health Organization. (2010). The sexual and reproductive health of young adolescents in developing countries: Reviewing the evidence, identifying research gaps, and moving the agenda. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70569/WHO_RHR_11.11_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[51] World Health Organization. (2017). Time to respond: A report on the global implementation of maternal death surveillance and response. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/249524/9789241511230-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[52] World Health Organization. (2019). Translating community research into global policy reform for national action: a checklist for community engagement to implement the WHO consolidated guideline on the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325776/9789241515627-eng.pdf?ua=1

[53] World Health Organization. (2010). Using human rights for sexual and reproductive health: improving legal and regulatory frameworks. https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/7/09-063412.pdf?ua=1.

[54] World Health Organization. (2013). 16 Ideas for addressing violence against women in the context of the HIV epidemic A programming tool. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/95156/9789241506533_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[55] World Health Organization. (2019). WHO consolidated guideline on self-care interventions for health executive summary. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325719/WHO-RHR-19.14-eng.pdf?ua=

[56] World Health Organization. (2016). WHO guidelines on the management of health complications from female genital mutilation. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/206437/9789241549646_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[57] World Health Organization. (2018). WHO recommendation: Elective C-section should not be routinely recommended to women living with HIV. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272454/WHO-RHR-18.08-eng.pdf?ua=

[58] World Health Organization. (2018). WHO recommendations Intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260178/9789241550215-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[59] World Health Organization. (2018). WHO recommendations on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275374/9789241514606-eng.pdf?ua=1

[60] World Health Organization. (2016). WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[61] World Health Organization. (2014). WHO technical guidance note: Strengthening the inclusion of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child (RMNCH) health in concept notes to the Global Fund. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128219/WHO_RHR_14.25_eng.pdf?sequence=1

Appendix 2

WHO documents cited in identified peer-reviewed articles that met inclusion criteria:

[1] World Health Organization. (2014). Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services guidance and recommendations. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/102539/9789241506748_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[2] World Health Organization. (2017). Responding to children and adolescents who have been sexually abused WHO clinical guidelines. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259270/9789241550147-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[3] World Health Organization. (2016). Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/249155/9789241511216-eng.pdf?sequence=1

[4] World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, & South African Medical Research Council. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf?sequence=1

[5] World Health Organization. (2012). Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/97415/9789241548717_eng.pdf?sequence=1

Funding Statement

This work was supported by World Health Organization [grant number APW 2018 986778-0].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abuya, T., Sripad, P., Ritter, J., Ndwiga, C., & Warren, C. E. (2018). Measuring mistreatment of women throughout the birthing process: Implications for quality of care assessments. Reproductive Health Matters, 26(53), 48–61. 10.1080/09688080.2018.1502018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, P. E., Bero, L., Montori, V. M., Brito, J. P., Stoltzfus, R., Djulbegovic, B., Neumann, I., Rave, S., & Guyatt, G. (2014). World health organisation recommendations are often strong based on low confidence in effect estimates. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(6), 629–634. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda, B., Chambers, A., & Johnson, J. (2014). Appraisal of guidelines developed by the World health organisation. Public Health, 128(5), 444–474. 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustreo, F., & Hunt, P. (2013). Women’s and children’s health: Evidence of impact of human rights. World Health Organisation. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/84203/9789241505420_eng.pdf;jsessionid=FCA9300CA3D7EC3972084507ACF35F65?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, J. P., Steyn, P. S., Gichangi, P., Kriel, Y., Milford, C., Munakampe, M., Njau, I., Nkole, T., Silumbwe, A., Smit, J., & Kiarie, J. (2019). Community and provider perspectives on addressing unmet need for contraception: Key findings from a formative phase research in Kenya, South Africa and Zambia (2015–2016). African Journal of Reproductive Health, 23(3), 106–119. 10.29063/ajrh2019/v23i3.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crankshaw, T. L., Kriel, Y., Milford, C., Cordero, J. P., Mosery, N., Steyn, P. S., & Smit, J. (2019). “As we have gathered with a common problem, so we seek a solution”: Exploring the dynamics of a community dialogue process to encourage community participation in family planning/contraceptive programmes. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 710. 10.1186/s12913-019-4490-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, M. L., Owolabi, O. O., Cresswell, J. A., Chelwa, N., Colombini, M., Vwalika, B., Mbizvo, M. T., & Campbell, O. (2019). A new approach to assess the capability of health facilities to provide clinical care for sexual violence against women: A pilot study. Health Policy and Planning, 34(2), 92–101. 10.1093/heapol/czy106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin, S., Ahmed, S., Bogecho, D., Ferguson, L., Hanefeld, J., MacCarthy, S., Raad, Z., & Steiner, R. (2012). Human rights in health systems frameworks: What is there, what is missing and why does it matter? Global Public Health, 7(4), 337–351. 10.1080/17441692.2011.651733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, M., Khosla, R., Krishnan, S., George, A., Gruskin, S., & Amin, A. (2016). How are gender equality and human rights interventions included in sexual and reproductive health programmes and policies: A systematic review of existing research foci and gaps. PLoS One, 11(12). 10.1371/journal.pone.0167542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High-Level Working Group on the Health and Human Rights of Women, Children and Adolescents, World Health Organization, United Nations . (2017). Leading the realization of human rights to health and through health: Report of the high-level Working group on the health and human rights of women, children and adolescents. World Health Organisation. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255540/1/9789241512459-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hoopes, A. J., Chandra-Mouli, V., Steyn, P., Shilubane, T., & Pleaner, M. (2015). An analysis of adolescent content in South Africa’s contraception policy using a human rights framework. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(6), 617–623. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Council . (2012). Technical guidance on the application of a human rights-based approach to the implementation of policies and programmes to reduce preventable maternal morbidity and mortality: Report of the office of the United Nations high commissioner for human rights. United Nations. https://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/women/docs/A.HRC.21.22_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, J. M., Oduyebo, T., Jatlaoui, T. C., Curtis, K. M., Whiteman, M. K., Zapata, L. B., & Gaffield, M. E. (2018). Dissemination and use of WHO family planning guidance and tools: A qualitative assessment. Health Research Policy and Systems, 16(1), 42. 10.1186/s12961-018-0321-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manu, A., Arifeen, S., Williams, J., Mwasanya, E., Zaka, N., Plowman, B. A., Jackson, D., Wobil, P., & Dickson, K. (2018). Assessment of facility readiness for implementing the WHO/UNICEF standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities - experiences from UNICEF’s implementation in three countries of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 531. 10.1186/s12913-018-3334-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) . (2012). Technical guidance on the application of a human rights-based approach to the implementation of policies and programmes to reduce preventable maternal morbidity and mortality, UN Doc. A/HRC/21/22. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) . (2014). Technical guidance on the application of a human rights-based approach to the implementation of policies and programmes to reduce and eliminate preventable mortality and morbidity of children under 5 years of age, UN Doc. A/ HRC/27/31. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) . (2015). Information series on sexual and reproductive health and rights. United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Samandari, G., Wolf, M., Basnett, I., Hyman, A., & Andersen, K. (2012). Implementation of legal abortion in Nepal: A model for rapid scale-up of high-quality care. Reproductive Health, 9(1), 7. 10.1186/1742-4755-9-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, D., Isba, R., Kredo, T., Zani, B., Smith, H., & Garner, P. (2013). World Health organization guideline development: An evaluation. PLoS One, 8(9). 10.1371/annotation/fd04e7c6-0d40-4d2c-a382-c5ad10074c99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N. T., Harker, K., Yameogo, W., Kouanda, S., Millogo, T., Menna, E. D., Lohani, J. R., Maharjan, O., Beda, S. J., Odinga, E. A., Ouattara, A., Ouedraogo, C., Greer, A., & Krause, S. (2017). Clinical outreach refresher trainings in crisis settings (S-CORT): clinical management of sexual violence survivors and manual vacuum aspiration in Burkina Faso, Nepal, and South Sudan. Reproductive Health Matters, 25(51), 103–113. 10.1080/09688080.2017.1405678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN . (2003). The human rights based approach to development cooperation towards a common understanding among UN agencies. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/human-rights-based-approach-development-cooperation-towards-common-understanding-among-un [Google Scholar]

- UNDP . (2012). Global commission on HIV and the law. Risks, rights and health. https://hivlawcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/FinalReport-RisksRightsHealth-EN.pdf [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA . (2010). A human rights-based approach to programming. https://www.unfpa.org/resources/human-rights-based-approach-programming [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2014). Ensuring human rights in the provision of contraceptive information and services guidance and recommendations. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/102539/9789241506748_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2017). Leading the realization of human rights to health and through health: Report of the high-level working group on the health and human rights of women, children and adolescents. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255540/9789241512459-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2019). Reproductive health library. https://extranet.who.int/rhl

- WHO . (2020a, May 15). Sexual and reproductive health: About HRP. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/hrp/en/

- WHO . (2020b, May 20). Sexual and reproductive health: Publications. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.