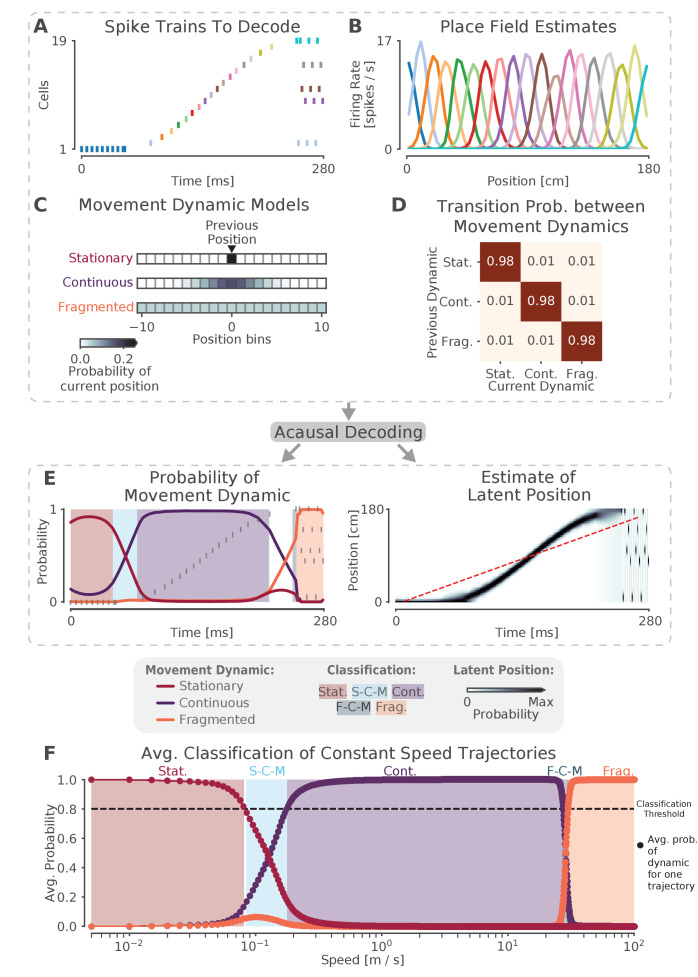

Figure 1. The model can capture different sequence dynamics on simulated data.

(A) We construct a firing sequence of 19 simulated place cells that exhibits three different movement dynamics. For the first 60 ms, one cell fires repeatedly, representing one stationary location. For next 190 ms, the cells fire in sequence, representing a rapid continuous trajectory along the virtual track. For the last 30 ms, cells fire randomly, out of spatial order, representing an fragmented spatial sequence. (B) Like the standard decoder, the state space model uses estimates of cells’ place fields from when the animal is moving and combines them with the observed spikes in (A) to compute the likelihood of position for each time step. (C) The prediction from the neural data is then combined with an explicit model of each movement dynamic, which determines how latent position can change based on the position in the previous time step. We show the probability of the next position bin for each movement dynamic model (color scale). Zero here represents the previous position. (D) The probability of remaining in a particular movement dynamic versus switching to another dynamic is modeled as having a high probability of remaining in a particular dynamic with a small probability of switching to one of the other dynamics at each time step. (E) The model uses the components in A-D over all time to decode the joint posterior probability of latent position and dynamic. This can be summarized by marginalizing over latent position (left panel) to get the probability of each dynamic over time. The shaded colors indicate the category of the speed of the trajectory at that time (Stat. = Stationary, S-C-M = Stationary-Continuous-Mixture, Cont. = Continuous, F-C-M = Fragmented-Continuous-Mixture, Frag. = Fragmented), which is determined from the probability. Marginalizing the posterior across dynamics also provides an estimate of latent position over time (right panel). Red dotted line in the right panel is the best fit line from the standard decoder using the Radon transform. (F) The probability of each dynamic depends heavily on the speed of the trajectory, as we show using a range of simulated spiking sequences each moving at a constant speed. Each dot corresponds to the average probability of that dynamic for a given constant speed sequence. We use a 0.80 threshold (dotted line) to classify each sequence based on the dynamic or dynamics which contribute maximally to the posterior (shaded colors).