Abstract

Objective

COVID-19-related social restrictions resulted in more loneliness, but whether this had further effects on mental health remains unclear. This study aimed at examining the longitudinal effects of COVID-19-related loneliness on mental health among older adults (aged ≥60 years) in Austria.

Study design

Survey data were gathered from a longitudinal observational study among a random sample of older Austrian adults. The first survey wave was conducted in May 2020 (N1 = 557), and the second wave was conducted in March 2021 (N2 = 463).

Methods

Data collection was based on either computer-assisted web or telephone interviewing. For statistical analysis, we used a cross-lagged panel analysis.

Results

The results showed the perceived COVID-19-related social restrictions to predict loneliness, which in turn predicted depressive and anxiety symptoms 10 months later.

Conclusions

COVID-19-related loneliness emerged as a risk factor for subsequent mental distress among older adults in Austria.

Keywords: COVID-19, Loneliness, Depressive symptoms, Anxiety symptoms

Introduction

Soon after the first diagnosed cases of COVID-19 in late 2019, the virus has spread quickly throughout the entire world. Consequently, wide-ranging governmental public health actions have been implemented, aiming to mitigate the spread of the disease and to prevent overburdened health systems. In Austria, these measures included stay-at-home orders and reducing the public and social life to a minimum. Given the strong age gradient in the risk of both hospitalization and death because of COVID-19, older adults may have been particularly affected by these restrictions, and the resulting social disconnectedness may have constituted a risk for loneliness and mental distress.1 , 2

In a recent study among older adults in Austria, Stolz et al.3 indeed registered substantial associations between the COVID-19 restriction measures during the first months of the pandemic (March to June 2020) and increased levels of loneliness, although potential delayed effects on mental health remain unclear. Thus, the present study examined the longitudinal effects of COVID-19-related loneliness during the first phase of the pandemic on symptoms of mental distress several months later. To this end, we assessed the mediating effects of loneliness in the relationship between the COVID-19-related social restrictions and both depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Methods

Data and sample

To answer this research question, we gathered data from two panel waves of an Austrian survey among older adults aged ≥60 years.3 The first wave was conducted in May 2020, and the second wave was conducted in March 2021. The majority of data (76% at wave one) was collected by means of a computer-assisted web interview (CAWI). To also ensure adequate coverage of people who are inaccessible via the internet, the remainder of participants (83% of which were aged ≥75 years) were questioned via a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI). Participants for the CAWI were randomly sampled from an online and offline pool of Austrian adults; sampling for the CATI relied on randomized last digit procedure. At wave 1, the sample size was N 1 = 557, with 83% of these adults also participating in wave 2 (N 2 = 463).

Measures

The measures included information on COVID-19-related social restrictions, feelings of loneliness, and symptoms of mental distress. To assess the perceived impact of COVID-19-related restriction measures on older adults’ social lives, participants had to indicate whether or not (“0 = no”; “1 = yes”) they were affected by each of seven social restrictions (e.g. not being able to see children or grandchildren in person; total score = 0–7; Supplementary Table A.1).

Feelings of loneliness were measured with the UCLA three-item loneliness scale.4 Participants were asked to indicate on a four-point rating scale how often they felt (1) “a lack of companionship,” (2) “left out,” or (3) “isolated” (total score = 3–12; Supplementary Table A.2).

Symptoms of mental distress were measured using items from the Brief Symptom Inventory.5 Participants had to indicate on a 5-point rating scale how much they suffered from different depressive and anxiety symptoms within the last 2 weeks. One of these depressive symptoms items (feeling lonely) was excluded to prevent conceptual overlap with the loneliness scale. The depressive symptoms scale (total score = 5–25) thus comprised five of six items, and the anxiety symptoms scale (total score = 6–30) included all six items (Supplementary Tables A.3 and A.4).

Further variables were sex (male/female), age in years, high school education or higher (yes/no), and living alone (yes/no).

Statistical analysis

To examine the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between the main variables, we performed a cross-lagged panel analysis using the R-package lavaan 0.6–3.6 To adequately account for the missing data, model estimation was conducted using full information maximum likelihood with robust standard errors.

Results

At wave 1, the average age of participants was 70 years (standard deviation = 6.6; range = 60–89). Fifty-two percent of participants were female, and 31% were living alone. Approximately 44% of participants completed high school education or had a university degree (Supplementary Materials B.1. and B.2.).

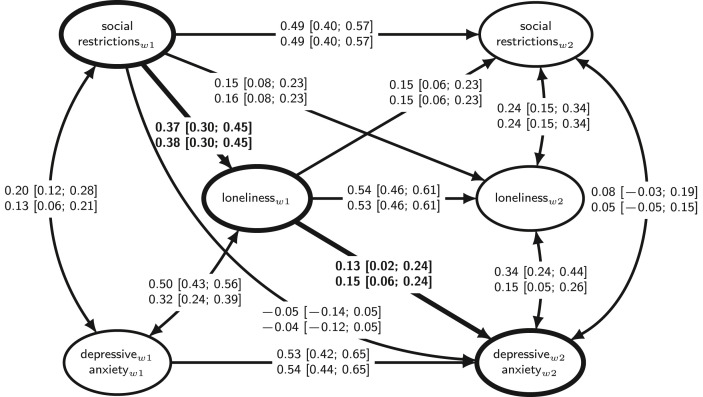

As regards cross-lagged panel analysis, we estimated separate models for both the depressive symptoms and the anxiety symptoms scales as the main outcome variables (Fig. 1 ). Both models demonstrated very good model fit (Supplementary Materials B.3.). At wave 1, both the social restrictions and loneliness were positively associated with depressive and anxiety symptoms. At the second wave, loneliness showed a positive correlation to both the depressive and anxiety symptoms and the social restrictions. Moreover, more perceived social restrictions at wave 1 predicted more loneliness at wave 2, and vice versa, higher levels of loneliness at wave 1 predicted more perceived social restrictions at wave 2.

Fig. 1.

We report the standardized parameter estimates (and the 95% confidence intervals within square brackets) for both the depressive symptoms (upper line) and the anxiety symptoms (lower line) models. Single-headed arrows reflect regression and two-headed arrows correlation effects. The thick lines and the bold font highlight the mediation pathway. Both models were controlled for age, sex, educational level, and living alone by regressing each of the main variables (at both waves) on each of these covariates. w1 = wave 1, w2 = wave 2.

As regards the mediation effect (see Fig. 1), it showed that more perceived social restrictions at wave 1 predicted higher levels of loneliness at the same point in time, which in turn predicted more depressive and anxiety symptoms at wave 2. This indirect effect was rather weak but significant for both the depressive symptoms (b = 0.05; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.01–0.09) and the anxiety symptoms (b = 0.06; 95% CI: 0.02–0.09) models. By contrast, no direct effect of social restrictions at wave 1 on depressive and anxiety symptoms at wave 2 was found.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is posing great challenges, and the entire impact of this crisis on social and mental health of older adults is yet to be understood. In this regard, the existing empirical evidence is inconsistent. Although some studies suggest that the pandemic had negative effects on older adults' feelings of loneliness and mental health,2 , 3 other studies emphasized older adults’ resilience.7, 8, 9

The findings of this study contribute to the literature by demonstrating potential delayed effects of COVID-19-related loneliness on older adults' mental health in Austria. In our analysis, we could show that higher levels of perceived COVID-19-related social restrictions predicted more feelings of loneliness, which in turn were predictive of more depressive and anxiety symptoms about 10 months later. These findings are in line with previous studies, highlighting the importance of having close social connections for an individual's mental health and emotional well-being and that social disconnectedness due to imposed or self-isolation, cessation of social activities, or reduced contact to family members and friends could be a source of loneliness and mental distress.1 , 3 , 10 Future research is encouraged to further investigate the long-term trends in loneliness and mental health that resulted from this unparalleled crisis.

Author statements

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Graz (32-368 ex 19/20; 33-226 ex 20/21).

Funding

None declared.

Competing interests

None declared.

Data availability

The survey data are available upon request. Moreover, data will be made available for scientific use via the Austrian Social Science Data Archive. The R-Code is available at: https://osf.io/ebvr9/.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.09.009.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Santini Z.I., Jose P.E., Cornwell E.Y., Koyanagi A., Nielsen L., Hinrichsen C. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e62–e70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Tilburg T.G., Steinmetz S., Stolte E., van der Roest H., de Vries D.H. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study among Dutch older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa111. gbaa111 https://10.1093/geronb/gbaa111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stolz E., Mayerl H., Freidl W. The impact of COVID-19 restriction measures on loneliness among older adults in Austria. Eur J Public Health. 2021;31:44–49. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes M.E., Waite L.J., Hawkley L.C., Cacioppo J.T. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys. Res Aging. 2004;26:655–672. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franke G.H., Ankerhold A., Haase M., Jäger S., Tögel C., Ulrich C. Der Einsatz des Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18) bei Psychotherapiepatienten. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2011;61:82–86. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270518. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270518. [Franke GH, Ankerhold A, Haase M, Jäger S, Tögel C, Ulrich C, et al. The usefulness of the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18) in psychotherapeutic patients. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2011;61:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48:1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kivi M., Hansson I., Bjälkebring P. Up and about: older adults' well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Swedish longitudinal study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76:e4–e9. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen T., Nilsen T.S., Yu B., Knapstad M., Skogen J.C., Vedaa Ø. Locked and lonely? A longitudinal assessment of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.1177/1403494821993711. 1403494821993711 https://10.1177/1403494821993711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng S., Roth A.R. Social isolation and loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study of U.S. adults older than 50. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbab068. gbab068 https://10.1093/geronb/gbab068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J., Mann F., Lloyd-Evans B., Ma R., Johnson S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:156. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The survey data are available upon request. Moreover, data will be made available for scientific use via the Austrian Social Science Data Archive. The R-Code is available at: https://osf.io/ebvr9/.