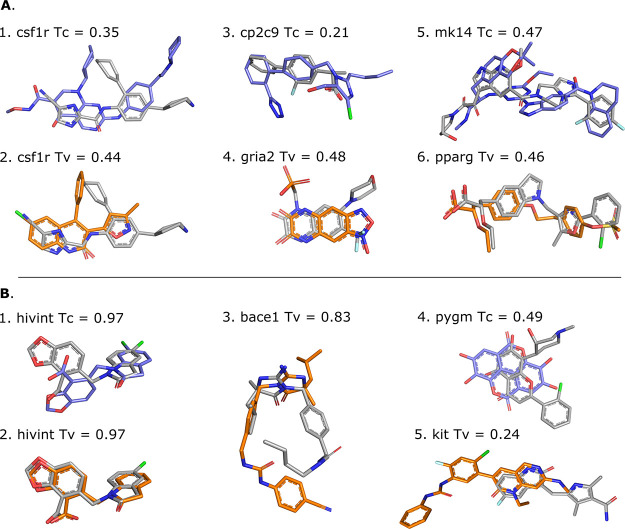

Figure 6.

Illustration of template (shape-based protocol: orange, pharmacophore-based protocol: blue) and target (grey) compounds. Panel (A) shows different template/target compound couples of low similarity, i.e., Tanimoto (Tc) or Tversky (Tv) coefficient of <0.5, which lead to successful docking. Templates 3dpk, 2i0v, 5x23, 3bki, 3ha8, and 1i7i were used for cases 1–6, respectively. Panel (B) shows scenarios that lead to docking failure for different possible reasons. While displaying high similarity with the target compounds, the hivint pharmacophore-based template compound adopts a different binding mode (B.1), and the shape-based template compounds leads to an unexpected failure that cannot be explained neither by the coverage nor their respective binding site (B.2). The shape-based template compound for bace1, which is the same as the pharmacophore-based template, adopts a different binding mode compared to the target despite the high similarity (B.3). Low shape, flexibility, and physicochemical similarities are observed between the template and the target compound for pygm (B.4); case B.5 is an example of a poor overlap between template and target compounds that is responsible for poor performance. Templates 3nf9, 3nf6, 3l5c, 3g72, and 6mob were used for cases 1–5, respectively.